After years--so many years--my book on the Forteans is finally coming out to the world! It will be released by the University of Chicago Press in June, 2024. All the juicy details can be found here.

|

After years--so many years--my book on the Forteans is finally coming out to the world! It will be released by the University of Chicago Press in June, 2024. All the juicy details can be found here.

2 Comments

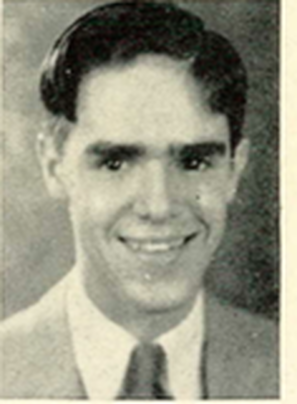

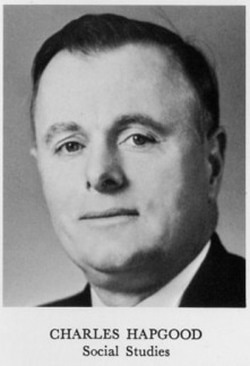

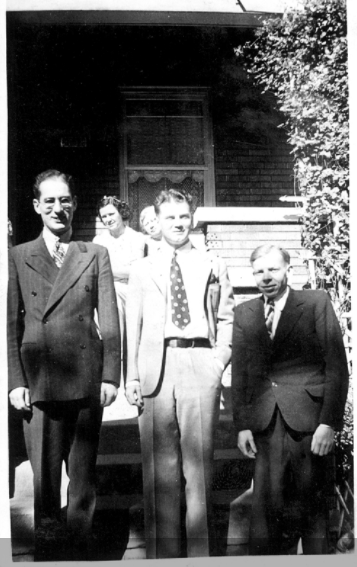

Martin Gardner, from his 1932 yearbook. Martin Gardner, from his 1932 yearbook. Surprised by Fort, but irritated by the Forteans. Whether he was a Fortean himself—well, that depends on how you define matters. Martin Gardner was born 21 October 1914 in Tulsa, Oklahoma, to James Henry Gardner, a petroleum geologist, and Willie Wilkerson Spiers. He had a younger brother and a younger sister. Gardner grew up on the Tulsa area. The family was fairly well off, employing servants and maids. As a youth, he developed an interest in puzzles and, around the age of ten, discovered Hugo Gernsback’s “Science and Invention”; he enjoyed Jules Verne and Sherlock Holmes, too, and when, in 1926, the first issue of “Amazing Stories” was advertised, he was a subscriber. Gardner also had an interest in magic. He attended Central High School, in Tulsa, where he practiced both gymnastics and tennis. At some point, he had cataract surgery, which made continuing to play tennis difficult. While in high school, he gave his physics teacher the run of “Amazing Stories” that he had collected. In 1930, when he was not yet 16, his first published writing appeared, a letter to “Science and Invention” in April, and a magic trick in “Sphix,” the following month. He would go on to write something on the order of a hundred books over the rest of his long life, many of these collections of essays he wrote for a number of different publications on a wide range of topics. He also spent some time at the University of Central Oklahoma; the 1932 yearbook described him as “an able cartoonist with an adept mind for science.”  Part of the vast Fortean network, though himself not much of a Fortean. Charles Hutchins Hapgood came out of the same Bohemian milieu that birthed the early Forteans, though he was a second generation: it was his mother and his father who were contemporaries of Dreiser and Hecht and De Casseres and their ilk. Charles was born 17 May 1904—making him two years younger than Thayer, and two years older than Fort’s search for anomalous reports—in New York City to the writers Hutchins Hapgood and Neith Boyce. Both Hutchins and Hapgood belonged to New York’s early twentieth-century Bohemia, their lives chronicled, by the Christine Stansell, among others—and themselves, Hutchins anonymously writing a memoir of his various affairs—the Hapgoods had an open marriage—that was published by Boni & Liveright (Fort’s publishers) the same season as “Book of the Damned.” The Hapgoods were a fairly prominent family of more than middling means. Charles was the second of four children, with an older brother Harry, and younger sisters Miriam and Beatrix. Neith found that her gender circumscribed her Bohemian freedoms, as she was moved out of the City to Westchester to raise them, while Harry continued his carousing. Charles attended Scarborough School in Westchester; the family had homes in both New York and Provincetown, Massachusetts. The family traveled quite a bit, which may be why they weren’t in the 1910 or 1920 censuses; Miriam was born in Florence. (His brother, Boyce, died in 1918, a victim of the influenza pandemic.) Charles continued travel, apparently spending a good portion of the 1920s abroad: he headed to England, France, Italy, and Switzerland for study and travel in October 1922, and doesn’t seem to have returned until July 1924. In February of the next year, documents show him returning from a Caribbean trip. He then attended Harvard, just as his father had, receiving an A.B. in 1929. The 1930 census has him living at home in Provincetown with his parents and and two sisters. Hutchins and Neith were both listed in the census as writers; Beatrix, twenty years old, was neither at school nor working. Miriam was a painter. He also made a short European trip this year, returning from France in June.  The central British Fortean. Eric Frank Russell was born in Berkshire, England, 6 January 1905. His father was an instructor at the Royal Military Academy. He’s ben the subject of a recent biography—Into Your Tent—and so my own biographical contribution will be brief, and this (very long) post will be mostly an intellectual history. He was raised in Egypt; he variously worked as a telephone operator, quantity surveyor, draughtsman, commercial traveller (something like a traveling salesman) and technical writer for a Liverpool steel company. He was influenced by the American (religious) skeptic, Robert Ingersoll. Russell discovered science fiction via the British Interplanetary Society in the mid-1930s, and started writing around that time. He became closely associated with the editor John W. Campbell, though he also published some in “Weird Tales.” Russell used a number of pseudonyms. He visited America in 1939, and in the 1940s served in the RAF, in which he worked as a wireless mechanic and radio operator. Russell spent more of his time writing int he late 1940s, but also continued to work elsewhere. He continued to be active through the 1950s, but his output dropped precipitously in the 1960s, mostly collections and reprints—this after a heart attack in 1959, the same year Tiffany Thayer died of one. John L. Ingham, his biographer, notes that Russell was coarse and sometimes hard to get along with. He cursed a lot, and wore his various prejudices on his sleeve: he was anti-Semitic and not fond of Italians. Russell was tall—6’2”—and lanky.  Julius Schwartz, Otto Binder, and Ray Palmer, 1938. Julius Schwartz, Otto Binder, and Ray Palmer, 1938. He was vast—he contained multitudes—and only one small part was Fortean. Raymond Alfred Palmer was born 1 August 1910 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, to Roy Clarence and the former Helena Martha Anna Steber. He would later fetishize his birth year, suggesting that he had seen Haley’s comet while still in utero, though in his memory he was held by his grandmother and shown the comet out the window. It is tempting to suggest, though no doubt too pat, that Palmer’s nostalgia was a reaction to what was otherwise a difficult childhood in many ways. The elder Palmer was a skilled laborer. In 1911, the family added a baby girl. Palmer was famously beautiful as a youngster, honored on a milk carton as one of Milwaukee’s healthiest babies. A brother would follow, in 1918, by which time Ray was suffering much. (Another brother would be born around 1929.) When he was seven, Ray was in an accident with a truck that badly damaged his spine. Operations would follow, pain, and a slow recovery that was never complete: he was left a hunchback and short, never growing more than about four feet tall. Amid his convalescence, Ray’s mother died; Ray resented his father, blaming him for slow medical treatment, for drinking too much and tomcatting around. Unable to go to school, Palmer—who had learned to read very young—escaped into books, and especially the newly developing genre of science fiction. By his own admission, Palmer was a fanciful child, and there is every reason to believe that the line, for him, between reality and imagination was incredibly thin; fantastic literature was a natural fit.  P. E. Cleator P. E. Cleator Henry Louis Mencken was born 12 September 1880 in Baltimore. He would grow up to be one of the most important public intellectuals of the early twentieth century, elitist, anti-democratic, and curmudgeonly, a foe of religion, contained Victorian values, bad thinking, loose language, and also the pseudosciences. Poke around a bit on line, and you’ll fine any number of references to him admiring Fort and being a member of the Fortean Society. This is wrong, very wrong. A life-long journalist, but also an editor, writer of books, and translator of Nietzsche, in 1908 Mencken became associated with the magazine The Smart Set. A few years later, he and George Jean Nathan became co-editors, fashioning the magazine into an important voice of modernist literature. Among those published in its pages—and there were many notables—was the Fortean enthusiast Benjamin DeCasseres. Mencken also championed Theodore Dreiser, valuing his attacks on American moral hypocrisy, even as he found his writing more often than not ponderous.  Sanderson with track from Clearwater, Florida. Sanderson with track from Clearwater, Florida. A fabulist and Fortean. Ivan Terence Sanderson was born 20 January 1911 in Edinburgh, Scotland, to Arthur Buchanan Sanderson, a whiskey maker, and Stella W. W. Robertson. According to Sanderson himself, he was a mosaic twin, born with three kidneys, and this may be true, but given Sanderson’s penchant for exaggeration, it is hard to accept without evidence. After World War I, his father moved to Kenya and turns da fair into a game preserve. He and Stella divorced in 1920, and Ivan was raised mostly by his mother, though he also visited his father. By accounts, Stella was strong-willed and controlling. After attending private schools, Ivan entered Eton College in 1924, were he continued his studies until 1927 in the natural sciences. In 1925, his father died. According to Sanderson, he was killed by a rhinoceros while helping the husband-and-wife team of filmmakers Martin and Osa Johnson. Sanderson’s admirer, Richard Grigonis notes that this isn’t actually correct, and the story Sanderson told about the death gets the details wrong in many ways, all favoring a better, more colorful story. The elder Sanderson was injured by a rhinoceros, but survived resigned his position with the movie-making team, and went to Nairobi for rehabilitation. He died 2-4 months later—accounts differ—either from complications or pneumonia (possibly different ways of saying the same thing).  A (con)founding Fortean. Benjamin DeCasseres was born 3 April 1873 in Philadelphia to David DeCasseres and the former Charlotte (Lottie) Davis. DeCasseres—spelled many ways, though Benjamin preferred it without the spaces—was an old Spanish-Portuguese Jewish family with deep roots in America and a collateral connection to the philosopher Baruch Spinoza. David, who had been born in Jamaica, was a bookkeeper; Charlotte had been born in Pennsylvania, to parents from Hungary and Bavaria. Benjamin was the oldest of four children, two sisters and a brother, Irma, Edith, and Walter. The family faced a good deal of upheaval in the early 1880s. Benjamin was attending the local schools. In 1880, aged only 3, Edith DeCasseres, his youngest sister, died. Two years later, the family had another child—that was Walter. In 1886, when he was 13, Benjamin dropped out of school and went to work for the Philadelphia Press, first as an office boy, but working his way up to proofreader. He stayed in the business until 1899. In early 1900, Walter was apparently trying to follow in Benjamin’s footsteps, and had called at a print shop, but presumably had been turned down, which is when tragedy revisited the family: he went missing February 4th. His body was later found floating in the Delaware River; police assumed he had drowned himself after not being able to find work. He was 18. News reports of the discovery appeared in the newspaper on Benjamin’s 27th birthday.  Bookish and fascinated by Fort, though he fairly quickly lost track of trends among Forteans. Joseph Henry Jackson was born 21 July 1894 in Madison, New Jersey to Herbert Hallet Jackson and Marion Agnes Brown. He had a younger brother named Gordon, born in 1898. At the time of the 1900 census, Herbert was an iron merchant. Later, Marion tutored music. In 1910, when he was about 16, Joseph was a stock runner. He attended Peddie, a private boarding school, and Lafayette College, in Easton Pennsylvania, from 1915 to 1917. His father died in 1914. He served in the U.S. ambulance corps during World War I, and afterwards moved to the San Francisco Bay Area, where ehe lived with his younger brother and mother. After a brief stint in advertising, Jackson was associated with Sunset magazine from 1920 to 1928, serving as editor for his last two years there—and so began his love affair with the West. On 20 June 1923, he married Charlotte Emanuella Cobden, in Berkeley; they had a daughter, Marion, name dafter his mother, in 1927. In 1924, while still with Sunset, he reviewed books—the program was “The Bookman’s Guide”—over Pacific Coast radio. He started in Oakland, before moving to San Francisco, then becoming syndicated. Jackson continued the radio work until 1943. He reviewed books of the San Francisco “Argonaut” from 1929 to 1930. In 1930, he went to work reviewing books for the San Francisco Chronicle (“A Bookman’s Notebook”), continuing until his death. His reviews were also carried by the Los Angeles Times starting in 1948.  Unimpressed by Fort—though dealing with him nonetheless—and irritated by the Forteans. Sam Moskowitz was born 30 June 1920 in Newark, New Jersey, to poor Russian immigrants Harry Moskowitz and the former Rose Gerber. I do not have reliable information on the family—the names were actually quite common, and it is hard to sort out who was the Harry, Rose, and Sam Moskowitz in question. Iy the early 1930s, according to the family, Harry was running a candy store. (Isaac Asimov, also the child of Russian immigrants, had parents who ran a candy store in New York as well.) It was there, at the store, that he encountered Astounding Stories, and became hooked by science fiction. He attended Central Commercial and Technical High School. He was a private in World War II, enlisted from 18 December 1942 to 20 October 1943, in the 610th Tank Destroyer Division. According to his military records, he had attended one year of college—but his obituary related that otherwise his family was too poor to send him to college. Moskowitz was publishing science fiction criticism by the time he was 17; “Are We Advocates of Scientific Fiction?,” appeared in the September-October 1937 issue of “Amateur Correspondent.” He wrote some fiction in the early 1940s, out of desperation for cash. After the war, he was uninterested in continuing to write fiction. He went to work in the food industry, first driving a produce truck, and later working as a salesman.He also continued with science fiction, running clubs and shaping himself into an important critic and, perhaps, the first true scholar of science fiction as a genre. |