Bookish and fascinated by Fort, though he fairly quickly lost track of trends among Forteans.

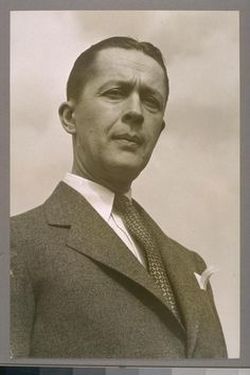

Joseph Henry Jackson was born 21 July 1894 in Madison, New Jersey to Herbert Hallet Jackson and Marion Agnes Brown. He had a younger brother named Gordon, born in 1898. At the time of the 1900 census, Herbert was an iron merchant. Later, Marion tutored music. In 1910, when he was about 16, Joseph was a stock runner. He attended Peddie, a private boarding school, and Lafayette College, in Easton Pennsylvania, from 1915 to 1917. His father died in 1914. He served in the U.S. ambulance corps during World War I, and afterwards moved to the San Francisco Bay Area, where ehe lived with his younger brother and mother.

After a brief stint in advertising, Jackson was associated with Sunset magazine from 1920 to 1928, serving as editor for his last two years there—and so began his love affair with the West. On 20 June 1923, he married Charlotte Emanuella Cobden, in Berkeley; they had a daughter, Marion, name dafter his mother, in 1927. In 1924, while still with Sunset, he reviewed books—the program was “The Bookman’s Guide”—over Pacific Coast radio. He started in Oakland, before moving to San Francisco, then becoming syndicated. Jackson continued the radio work until 1943. He reviewed books of the San Francisco “Argonaut” from 1929 to 1930. In 1930, he went to work reviewing books for the San Francisco Chronicle (“A Bookman’s Notebook”), continuing until his death. His reviews were also carried by the Los Angeles Times starting in 1948.

Joseph Henry Jackson was born 21 July 1894 in Madison, New Jersey to Herbert Hallet Jackson and Marion Agnes Brown. He had a younger brother named Gordon, born in 1898. At the time of the 1900 census, Herbert was an iron merchant. Later, Marion tutored music. In 1910, when he was about 16, Joseph was a stock runner. He attended Peddie, a private boarding school, and Lafayette College, in Easton Pennsylvania, from 1915 to 1917. His father died in 1914. He served in the U.S. ambulance corps during World War I, and afterwards moved to the San Francisco Bay Area, where ehe lived with his younger brother and mother.

After a brief stint in advertising, Jackson was associated with Sunset magazine from 1920 to 1928, serving as editor for his last two years there—and so began his love affair with the West. On 20 June 1923, he married Charlotte Emanuella Cobden, in Berkeley; they had a daughter, Marion, name dafter his mother, in 1927. In 1924, while still with Sunset, he reviewed books—the program was “The Bookman’s Guide”—over Pacific Coast radio. He started in Oakland, before moving to San Francisco, then becoming syndicated. Jackson continued the radio work until 1943. He reviewed books of the San Francisco “Argonaut” from 1929 to 1930. In 1930, he went to work reviewing books for the San Francisco Chronicle (“A Bookman’s Notebook”), continuing until his death. His reviews were also carried by the Los Angeles Times starting in 1948.

Starting in the 1930s, Jackson put out a number of books, mostly on the American West, particularly the San Francisco region. He also did a travel book about an excursion he and Charlotte took through Mexico. Jackson was (along with another Fortean, Ben Abrams) an early champion of John Steinbeck. He and Charlotte became friends with John and Carol Steinbeck, and even met up with them in Mexico. Jackson was also encouraging of other younger authors (including fellow Fortean Anthony Boucher). After his death, the an award was created in his name as a grant to help new authors.

Joseph Henry Jackson died of a stroke while taping a book review for NBC radio on 15 July 1955. He was 60.

**************

As is usually the case when I write these biographies, I do not know when Jackson first came across Fort. As readerly as he was, it could have been at any time, and for a number of reasons: recommendations to read Fort by Woollcott or Tarkington or Dreiser; the hullabaloo surrounding the Fortean Society; hearing from Anthony Boucher; or his own interest in ghosts and poltergeists. His interest seems to have been deepest in the early 1940s, before delving into fond memories. At the center, though, was a moment of intense Fortean activity right near his home.

To the best of my knowledge, Jackson’s first public mention of Fort came in a review of the omnibus edition of Fort’s books. It was clear from it that he knew of Fort’s books already, and the Society, and may have even considered himself something of a Fortean, but had not read the book itself before writing about it: he was going on memories. What he really wanted to do was introduce readers to the Fortean Society and Fort, whom he thought of as a gadfly, a spur to thought, with some interesting writerly tricks, though also a sometimes unfortunate style. On 1 May 1941, Jackson wrote, in part,

“Fort’s favorite occupation was saying ‘No!’ or, at the very least, ‘Oh, Yeah?’ His interest was all of life, but specifically physics and astronomy. To the physicists and astronomers, Fort made a lifelong habit of saying ‘Is that so? Well, how do you know?’ Sometimes they found him very difficult to answer.

“What interested Fort particularly in the field of physics were such manifestations as unexplained showers of stones, cloudbursts of frogs or fish, Chinese seals found in Ireland, rattling roofs, thumping tables—such matters by the thousand.

“Fort made records over periods of years, collecting and filing reports of such unexplained phenomena. Then he wrote about them, and put forward some of his own mild notions and asked the scientists please to tell him the why of them all. For good measure, and because he was a writer, Fort made a habit of presenting his material with a kind go gigantic irony the was often misunderstood in his lifetime. He did not state some of his magnificent paradoxes because he believed in them. His purpose was, by the process of reduction to absurdity, to awaken the slumbering mind, if not of the scientist at least of some of his lay readers. ‘Look,’ he kept saying, in essence, ‘there are a lot of unexplained things that go on in this world. The scientists try to hush them up because they haven’t the answers either. But the sooner we face the unexplained for what it is, the more likely we are able to explain it some day.’

. . . “It was Fort’s chosen life work to be a gadfly—a massive, spectacled gadfly who wrote like a Rabelais who had decided not to be nasty, but a gadfly nonetheless. . . .A lot of readers are not going to like some things about Fort. He is not always easy to read. His habit of writing, as I think Thayer once sid, as though he were scrawling on a cliff with a charred stub of a redwood tree, puts a great many people off. In the case of such a man, the simple thing is to set him down as mad, and many have done that.

“But in such cases, too, there is always the teasing thought: What if he happens to be sane and the rest of us are batty? Well, if that not in occurs to you when you read Charles Fort, then you’ve made the first step toward becoming a Fortean, because you’ve shifted into a dimension new to you. You’ve said ‘What if . . . ?’

“That’s all you need to start you on the Fortean road. Just begin saying to yourself, ‘Yes, but what if . . . ?’ It’ll be good for you.”

Jackson was still mulling Fort and Fortean topics more generally a couple of years later. In 1943, he wrote an introduction to Ambrose Bierce’s “Tales of Soldiers and Civilians” that mentioned—without naming—Robert Heinlein’s story “Lost Legion,” which had imagined that Bierce did not get lost in Mexico—not killed there, either—but retreated to Mt. Shasta, mystical home of Lemuria, where he joined a band of psychic adepts. It was clear that Jackson was not taken with Heinlein’s story, but still had some sympathy for Fortean speculations. He immediately followed discussion of “Lost Legion” by remarking on Fort’s observation—from “Wild Talents” that “possibly some demonic force, for reasons of its own, was collecting Ambroses.” In line with his review of FOrt’s books from a few years back, Jackson took this not as a conclusion, but an invitation for musing:

“The notion is no more curious than some that have been solemnly offered as the truth. Certainly Bierce himself, if he could have known about the to-do his vanishment caused, would have commented even more sardonically on the subject of such commotion over an unknown.”

By this point, if not before, Jackson was aware of the wider Fortean community, even if he did not consider himself a member (he had only taken a few steps along the road, his review seemed to say) nor a careful follower. He’d read Fort, and knew of Heinlein. Anthony Boucher was filling in at the Chronicle for a reviewer who had gone off to war—and they shared a number of interests, not only Fort, but the mystery genre, generally, and Sherlock Holmes specifically, forming a branch of the Baker Street Irregulars. Jackson also knew the San Francisco writer Miriam Allen De Ford, who was also a fan of Charles Fort, and had, indeed, investigated a rain of stones of stones in Chicago, California, for Fort, back in the twenties. Jackson was also aware of “Doubt” and the experimental literary journal “Circle”—which had Fortean connections—being published in Berkeley.

Over time, though, his interest in Fort and Forteanism ebbed, his ideas about the man and the movement something he remembered rather tan something he engaged, a museum piece. Already his review of the omnibus Fort suggested he had not careful read Fort in a while (if, to be fair, at all): the quotation he attributed to Thayer, about Fort writing with a charred piece of redwood, was something Fort had written himself, in New Lands: “Char me the trunk of a redwood tree. Give me pages of white chalk cliffs to write upon. Magnify me thousands of times, and replace my trifling immodesties with a titanic megalomania- -then might I write largely enough for our subjects.” By the 1940s, his connections to Forteanism would have been more tenuous: he broke with Boucher in 1947, over some intemperate remarks Boucher supposedly made about poor pay and working conditions at the Chronicle, the two of them not speaking for some half-decade; Circle stopped publishing (even as Doubt became more reliably produced); and the other matters took precedence.

But Fort remained there, a touchstone. In 1952, amid a review for Nandor Fodor and hereward Carrington’s book “Haunted People,” Jackson had occasion to bring up Fort: “Chief among the ‘explanations’ commonly used to clear up poltergeist phenomena, so-called, is the ancient one that the whole business is the work of some ‘naughty boy or girl.’ In fact, anyone who has done any reading in the field must be struck by the number of times this ‘explanation’ occurs spontaneously to policemen, parents, neighbors and other investigators. “Appropos, the late Charles Fort, who did some digging of his own into just-this field, once wrote testily, ‘Why is it never a naughty old lady, for instance?’ . . . Books of this sort have always had a special fascination for many readers, and I’ll confess I too enjoy following such cases and seeing what the author has to say.

“I’m afraid, though, that even though I don’t find the ‘naughty child’ theory very impressive—one returns to Fort’s question, ‘Why never a naughty old lady, for instance?’—I’d still like to know more than I do about such phenomena.”

He scratched the same itch, two years later, while reviewing a Jesuit book on the subject, “Ghosts and Poltergeists”:

“Readers in the field will doubtless have come across the works of the late Charles Fort, who was pretty well convinced of the occurrence of such phenomena, though he liked to use the word ‘teleportation’ to define particularly the showers of stones, fish or whatever that have been recorded, rather than to attribute them to spirits of any kind.

“It was Fort, in fact, who in the pursuit of such happenings grew so sick and tired of the familiar pattern—stones, mystery, police, investigators, frustration and the final invariable report: ‘It was all done by naughty small boys!’ His comment, one of the most wonderful ever made about such things was, ‘If only, just once, somebody would blame it on a naughty old lady!’

On display here was, again, his affection for Fort’s obstinate questioning and openness to unusual topics (even if, ultimately, he wanted these things explained scientifically). As well there was his refusal to quote Fort correctly, for whatever reason—though probably because the collected works were so long, and it was so difficult to find an exact passage, especially if one did not make the habit of reading Fort regularly. Indeed, I cannot find a quote like the one Jackson attributes to Fort, and, at any rate, Fort suggested there were such things as poltergeist girls in “Wild Talents” (even while ridiculing the use of children as an explanation for such phenomena).

That Jackson was no longer following Fortean phenomena, though he once had, is undeniable from this later review. He said that the latest recorded occurrence of poltergeist “anywhere near where I live” came from the late summer of 1943. That wasn’t true. But there had been an event back then, one that riveted the Bay Area Forteans—him, Boucher, and De Ford. One that occurred in Oakland, very nearby to Boucher and Jackson in Berkeley, and close to De Ford. But none of them had gotten out there, Jackson blamed the war: “But I’ve always been sorry that the shortage of gasoline ration tickets kept me from going out to have a look for myself, and so are others I know hereabouts. We mightn’t have caught either a naughty boy or a mischievous old lady but the firsthand experience would have been worth having.”

As he remembered the events, more than a decade later, it followed the typical pattern, the one he criticized, and the one that Tiffany Thayer wanted to make a Fortean law: blame it on the child, especially the young girl: “The familiar pattern was the same—showers of stones; a young girl in the house; baffled police; even mored baffle newspapers; and then the payoff, exactly as usual, ‘It was bad boys!’” Reconstructing the events of the last few weeks of August 1943 is actually quite difficult, the evidence fragmentary and not always inspiring confidence, but ti does seem to have had the usual ambiguity, the displaced young girl and unaccountable activities.

Events started in the middle of August 1943, at 1629 89th Avenue, in East Oakland. Stones fell on the house at different times of day and night, according to reports, some of them small like pebbles, some of them large; most of them apparently were washed out, the color of construction gravel—though supposedly there was no construction on-going. This was not the only place in Oakland where weird things were falling, according to reports. Across town, small bombs were being thrown off a highway bridge near passers-by below. (In this case, construction workers saw the boys responsible, though could not catch them.) According to one report, the rain of rocks onto the small white stucco house at 1629 89th avenue stopped abruptly on 1 September, after pock-marking the facade and roof, accumulating in the yard, and even occasionally hitting the residents.

As far as I know, Jackson was wrong in the events being blamed on naughty kids. I do not believe that there was ever an official explanation. Many years after the fact, Fortean investigator Brad Steiger said that a psychic investigator blamed seagulls and that there was an inconclusive investigation by some people attached to the University of California. The police watched the house, too—the newspapers called it a vigil—though, again as far as I know—never caught a perpetrator or explained the events. It was left a mystery. According to an article in the Oakland Tribune, “Oakland police officers scratched their heads in bewilderment last night as they continued their investigation of a case which, they agreed, has all the earmarks of a phenomenon.”

As it happens, from what I can make out, there were a couple of young girls living in the house at the time, and the family was under some stress. The newspaper stories say the house was occupied by Mrs. Irene Fellows, a grandmother. This would be the former Irene Carlile (not to be confused with the poet and folklorist Irene Carlisle, who also lived in Oakland around this time), who was 56 at the time. Irene’s second husband was Thomas Jefferson Fellows, and their marriage seemed to be under some strain—according to the 1940 census, Thomas was living in Dallas, as a lodger, and was reported as single. At any rate, he was back in Oakland by 1943 (and would die the following year).

Irene’s first marriage had been to Arthur Mayrand. They’d had two daughters, Lucille and Vivian, and each daughter had a daughter. Vivian had married Earl C. Waid, and had given birth to Donna. Lucille had been briefly married to E. W. Mike Hosier, and given birth to Audrey Lee, but by 1940 had married Vernon Waid. The unusual spellings of the last name is a clue that Lucille and Vivian had married brothers. Vivian would marry for a second time by 1945, which may account for why her daughter, Donna, aged five, would be living with Irene at the time of the rock-falling incidents. Audrey was with her mother and stepfather in 1940, but war work may have meant she needed to stay with her grandmother as well.

The war was certainly having an effect not he family, as it was on all of Oakland—there was a huge housing crunch and influx of people to work in the Oakland shipyards. Irene, who was trained as a nurse, may have been doing some war work; Thomas, Irene’s husband, was working for the war department at Ft. Mason. (His 1942 draft card has him living in Berkeley, and gives as his emergency contact information a family member in Florida, not Irene.) Mike Hosier had joined the military in December of 1942. A gunner in the Pacific, he was reported to be hospitalized on 10 August 1943, at the time nine-year-old Audrey was with her grandmother. (Two years later, Audrey would be killed when she rode her bike into a car driven by a navy seaman while living in Santa Cruz.) At the time of the mysterious showers, though, she would have been living with a grandmother, a cousin twice-over, and worried about her injured biological father. It could not have been easy.

Whatever was going on the house at the time—and there’s no indication that the newspapers got it all correct, and I, writing from three-quarters-of-a-century later, using fragmentary documents definitely do not have a good grasp on events—the story of the sone falls did make capture attention. The Tribune wrote about it; so did the Chronicle. Boucher and de Ford made each other’s acquaintance over the matter. Later, a publication by Manly Hall Palmer, the occultist, and a Theosophical magazine would comment on the events, as would Steiger. And Joseph Henry Jackson used the news story as a peg for another article on Fort.

This one appeared 1 September 1943, in the Chronicle.

”So stones have been falling from nowhere in Oakland!

“Not so many years ago stones fell from nowhere in Chico. On the records are showers of stones—some even inside closed rooms—dropping all over the globe, in Scotland, in India, in Alabama, like stars falling. Newspapers cover the story each time; the police investigate; it’s bad boys somewhere behind the next house, out of sight. And the stones go on falling.

“Perhaps you read yesterday’s Chronicle story of latest developments in, around and upon the house of Mrs. Irene Fellows. If you did, and happened to be a reader of the works of Charles Fort, you were particularly interested. For Mr. Fort, during his lifetime, collected and wrote about reports of just this kind—showers of stones, of mud, of periwinkles, red rains and black rains, little fishes deposited upon a Surrey farm, odd ‘explosions’ (noises anyway), water dripping from the ceiling of a room in dry weather. The Chronicle reporter, in fact, mentioned one of the books of Mr. Fort, his ‘Wild Talents,’ in connection with the case of Grandma Fellows.

“Charles Fort: even in his lifetime (he died in 1932), was not widely read, in spite of the efforts of a group of interested citizens to promote his books. But his writings are available now in one volume, ‘The Books of Charles Fort’ (Henry Holt; $4.00), with an introduction by Tiffany Thayer, one of the most active loving spirits in the Fortean Society.

“And this seems as good a time as any, perhaps better than most, to remind you of Fort and his writing, and to introduce him, maybe to some who haven’t yet come across him.

“The Indefatigable Clip-Collector

“On the surface, Charles Fort was simply a man with a curious taste for collecting clippings from newspapers and periodicals, provided the stories related to unexplained happenings.

“Underneath, Fort was much more than this. He was no mere crank. He had as sound a purpose in doing what he did as any of the scientists about whom he enjoyed being so skeptical.

“His purposes, and those of the Fortean Society, are epitomized by Mr. Thayer in his introduction to ‘The Books of Charles Fort.’ What Fort was after was to remove the halo from the head of science to make people think; to destroy, if possible, the faith of scientists in their own works, thus compelling a general return to the truly scientific principle of ‘temporary acceptance.’

“To help in accomplishing these ends, Fort wrote four books, all of which are incorporated in one volume: ‘Wild Talents,’ ‘Lo!’ ‘New Lands’ and ‘The Book of the Damned.’ He wrote them, as Thayer once said, with a charred redo tree on the face of a cliff. This is to say, Fort wrote with a fine sense of exaggeration—exaggeration with a purpose. He flung words about magnificently. He indulged his Gargantuan sense of humor as he pleased. He juggle paradoxes and played games with words—even with sentence structure. But one thing he didn’t play with. He never made fun of ideas. To Fort, an idea (provided you didn’t say that the idea was the one and only truth) was the whole purpose of living and thinking. Ideas—new ideas about old things—were what he wanted to stimulate.

“Are Falling Stones ‘Teleportation’?

“But to come back to falling stones.

“Fort examined all sorts of curious occurrences. In the matter of stones and other substances ‘falling from the sky,’ however, he suggested (tongue in cheek, if you like) a theory of ‘teleportation.’ . . .

“Note that Fort doesn’t say ‘I think this is so.’ He never does that. He only suggests that he’s tired of tales about naughty boys, or whirlwinds carefully selecting frogs from a pond and including no mud or tadpoles; he’s tired of science smugly saying: ‘Oh, nonsense’ to any solutions but its own.

“But you’d better read him. Wile you’re reading you won’t be sure if you’re on your head or your heels. But then Fort knew that. He wrote to shake up his reader. He does. And the time to read him is when a story like that of Grandma Fellows and her rock-shower is fresh in your mind.”

Joseph Henry Jackson died of a stroke while taping a book review for NBC radio on 15 July 1955. He was 60.

**************

As is usually the case when I write these biographies, I do not know when Jackson first came across Fort. As readerly as he was, it could have been at any time, and for a number of reasons: recommendations to read Fort by Woollcott or Tarkington or Dreiser; the hullabaloo surrounding the Fortean Society; hearing from Anthony Boucher; or his own interest in ghosts and poltergeists. His interest seems to have been deepest in the early 1940s, before delving into fond memories. At the center, though, was a moment of intense Fortean activity right near his home.

To the best of my knowledge, Jackson’s first public mention of Fort came in a review of the omnibus edition of Fort’s books. It was clear from it that he knew of Fort’s books already, and the Society, and may have even considered himself something of a Fortean, but had not read the book itself before writing about it: he was going on memories. What he really wanted to do was introduce readers to the Fortean Society and Fort, whom he thought of as a gadfly, a spur to thought, with some interesting writerly tricks, though also a sometimes unfortunate style. On 1 May 1941, Jackson wrote, in part,

“Fort’s favorite occupation was saying ‘No!’ or, at the very least, ‘Oh, Yeah?’ His interest was all of life, but specifically physics and astronomy. To the physicists and astronomers, Fort made a lifelong habit of saying ‘Is that so? Well, how do you know?’ Sometimes they found him very difficult to answer.

“What interested Fort particularly in the field of physics were such manifestations as unexplained showers of stones, cloudbursts of frogs or fish, Chinese seals found in Ireland, rattling roofs, thumping tables—such matters by the thousand.

“Fort made records over periods of years, collecting and filing reports of such unexplained phenomena. Then he wrote about them, and put forward some of his own mild notions and asked the scientists please to tell him the why of them all. For good measure, and because he was a writer, Fort made a habit of presenting his material with a kind go gigantic irony the was often misunderstood in his lifetime. He did not state some of his magnificent paradoxes because he believed in them. His purpose was, by the process of reduction to absurdity, to awaken the slumbering mind, if not of the scientist at least of some of his lay readers. ‘Look,’ he kept saying, in essence, ‘there are a lot of unexplained things that go on in this world. The scientists try to hush them up because they haven’t the answers either. But the sooner we face the unexplained for what it is, the more likely we are able to explain it some day.’

. . . “It was Fort’s chosen life work to be a gadfly—a massive, spectacled gadfly who wrote like a Rabelais who had decided not to be nasty, but a gadfly nonetheless. . . .A lot of readers are not going to like some things about Fort. He is not always easy to read. His habit of writing, as I think Thayer once sid, as though he were scrawling on a cliff with a charred stub of a redwood tree, puts a great many people off. In the case of such a man, the simple thing is to set him down as mad, and many have done that.

“But in such cases, too, there is always the teasing thought: What if he happens to be sane and the rest of us are batty? Well, if that not in occurs to you when you read Charles Fort, then you’ve made the first step toward becoming a Fortean, because you’ve shifted into a dimension new to you. You’ve said ‘What if . . . ?’

“That’s all you need to start you on the Fortean road. Just begin saying to yourself, ‘Yes, but what if . . . ?’ It’ll be good for you.”

Jackson was still mulling Fort and Fortean topics more generally a couple of years later. In 1943, he wrote an introduction to Ambrose Bierce’s “Tales of Soldiers and Civilians” that mentioned—without naming—Robert Heinlein’s story “Lost Legion,” which had imagined that Bierce did not get lost in Mexico—not killed there, either—but retreated to Mt. Shasta, mystical home of Lemuria, where he joined a band of psychic adepts. It was clear that Jackson was not taken with Heinlein’s story, but still had some sympathy for Fortean speculations. He immediately followed discussion of “Lost Legion” by remarking on Fort’s observation—from “Wild Talents” that “possibly some demonic force, for reasons of its own, was collecting Ambroses.” In line with his review of FOrt’s books from a few years back, Jackson took this not as a conclusion, but an invitation for musing:

“The notion is no more curious than some that have been solemnly offered as the truth. Certainly Bierce himself, if he could have known about the to-do his vanishment caused, would have commented even more sardonically on the subject of such commotion over an unknown.”

By this point, if not before, Jackson was aware of the wider Fortean community, even if he did not consider himself a member (he had only taken a few steps along the road, his review seemed to say) nor a careful follower. He’d read Fort, and knew of Heinlein. Anthony Boucher was filling in at the Chronicle for a reviewer who had gone off to war—and they shared a number of interests, not only Fort, but the mystery genre, generally, and Sherlock Holmes specifically, forming a branch of the Baker Street Irregulars. Jackson also knew the San Francisco writer Miriam Allen De Ford, who was also a fan of Charles Fort, and had, indeed, investigated a rain of stones of stones in Chicago, California, for Fort, back in the twenties. Jackson was also aware of “Doubt” and the experimental literary journal “Circle”—which had Fortean connections—being published in Berkeley.

Over time, though, his interest in Fort and Forteanism ebbed, his ideas about the man and the movement something he remembered rather tan something he engaged, a museum piece. Already his review of the omnibus Fort suggested he had not careful read Fort in a while (if, to be fair, at all): the quotation he attributed to Thayer, about Fort writing with a charred piece of redwood, was something Fort had written himself, in New Lands: “Char me the trunk of a redwood tree. Give me pages of white chalk cliffs to write upon. Magnify me thousands of times, and replace my trifling immodesties with a titanic megalomania- -then might I write largely enough for our subjects.” By the 1940s, his connections to Forteanism would have been more tenuous: he broke with Boucher in 1947, over some intemperate remarks Boucher supposedly made about poor pay and working conditions at the Chronicle, the two of them not speaking for some half-decade; Circle stopped publishing (even as Doubt became more reliably produced); and the other matters took precedence.

But Fort remained there, a touchstone. In 1952, amid a review for Nandor Fodor and hereward Carrington’s book “Haunted People,” Jackson had occasion to bring up Fort: “Chief among the ‘explanations’ commonly used to clear up poltergeist phenomena, so-called, is the ancient one that the whole business is the work of some ‘naughty boy or girl.’ In fact, anyone who has done any reading in the field must be struck by the number of times this ‘explanation’ occurs spontaneously to policemen, parents, neighbors and other investigators. “Appropos, the late Charles Fort, who did some digging of his own into just-this field, once wrote testily, ‘Why is it never a naughty old lady, for instance?’ . . . Books of this sort have always had a special fascination for many readers, and I’ll confess I too enjoy following such cases and seeing what the author has to say.

“I’m afraid, though, that even though I don’t find the ‘naughty child’ theory very impressive—one returns to Fort’s question, ‘Why never a naughty old lady, for instance?’—I’d still like to know more than I do about such phenomena.”

He scratched the same itch, two years later, while reviewing a Jesuit book on the subject, “Ghosts and Poltergeists”:

“Readers in the field will doubtless have come across the works of the late Charles Fort, who was pretty well convinced of the occurrence of such phenomena, though he liked to use the word ‘teleportation’ to define particularly the showers of stones, fish or whatever that have been recorded, rather than to attribute them to spirits of any kind.

“It was Fort, in fact, who in the pursuit of such happenings grew so sick and tired of the familiar pattern—stones, mystery, police, investigators, frustration and the final invariable report: ‘It was all done by naughty small boys!’ His comment, one of the most wonderful ever made about such things was, ‘If only, just once, somebody would blame it on a naughty old lady!’

On display here was, again, his affection for Fort’s obstinate questioning and openness to unusual topics (even if, ultimately, he wanted these things explained scientifically). As well there was his refusal to quote Fort correctly, for whatever reason—though probably because the collected works were so long, and it was so difficult to find an exact passage, especially if one did not make the habit of reading Fort regularly. Indeed, I cannot find a quote like the one Jackson attributes to Fort, and, at any rate, Fort suggested there were such things as poltergeist girls in “Wild Talents” (even while ridiculing the use of children as an explanation for such phenomena).

That Jackson was no longer following Fortean phenomena, though he once had, is undeniable from this later review. He said that the latest recorded occurrence of poltergeist “anywhere near where I live” came from the late summer of 1943. That wasn’t true. But there had been an event back then, one that riveted the Bay Area Forteans—him, Boucher, and De Ford. One that occurred in Oakland, very nearby to Boucher and Jackson in Berkeley, and close to De Ford. But none of them had gotten out there, Jackson blamed the war: “But I’ve always been sorry that the shortage of gasoline ration tickets kept me from going out to have a look for myself, and so are others I know hereabouts. We mightn’t have caught either a naughty boy or a mischievous old lady but the firsthand experience would have been worth having.”

As he remembered the events, more than a decade later, it followed the typical pattern, the one he criticized, and the one that Tiffany Thayer wanted to make a Fortean law: blame it on the child, especially the young girl: “The familiar pattern was the same—showers of stones; a young girl in the house; baffled police; even mored baffle newspapers; and then the payoff, exactly as usual, ‘It was bad boys!’” Reconstructing the events of the last few weeks of August 1943 is actually quite difficult, the evidence fragmentary and not always inspiring confidence, but ti does seem to have had the usual ambiguity, the displaced young girl and unaccountable activities.

Events started in the middle of August 1943, at 1629 89th Avenue, in East Oakland. Stones fell on the house at different times of day and night, according to reports, some of them small like pebbles, some of them large; most of them apparently were washed out, the color of construction gravel—though supposedly there was no construction on-going. This was not the only place in Oakland where weird things were falling, according to reports. Across town, small bombs were being thrown off a highway bridge near passers-by below. (In this case, construction workers saw the boys responsible, though could not catch them.) According to one report, the rain of rocks onto the small white stucco house at 1629 89th avenue stopped abruptly on 1 September, after pock-marking the facade and roof, accumulating in the yard, and even occasionally hitting the residents.

As far as I know, Jackson was wrong in the events being blamed on naughty kids. I do not believe that there was ever an official explanation. Many years after the fact, Fortean investigator Brad Steiger said that a psychic investigator blamed seagulls and that there was an inconclusive investigation by some people attached to the University of California. The police watched the house, too—the newspapers called it a vigil—though, again as far as I know—never caught a perpetrator or explained the events. It was left a mystery. According to an article in the Oakland Tribune, “Oakland police officers scratched their heads in bewilderment last night as they continued their investigation of a case which, they agreed, has all the earmarks of a phenomenon.”

As it happens, from what I can make out, there were a couple of young girls living in the house at the time, and the family was under some stress. The newspaper stories say the house was occupied by Mrs. Irene Fellows, a grandmother. This would be the former Irene Carlile (not to be confused with the poet and folklorist Irene Carlisle, who also lived in Oakland around this time), who was 56 at the time. Irene’s second husband was Thomas Jefferson Fellows, and their marriage seemed to be under some strain—according to the 1940 census, Thomas was living in Dallas, as a lodger, and was reported as single. At any rate, he was back in Oakland by 1943 (and would die the following year).

Irene’s first marriage had been to Arthur Mayrand. They’d had two daughters, Lucille and Vivian, and each daughter had a daughter. Vivian had married Earl C. Waid, and had given birth to Donna. Lucille had been briefly married to E. W. Mike Hosier, and given birth to Audrey Lee, but by 1940 had married Vernon Waid. The unusual spellings of the last name is a clue that Lucille and Vivian had married brothers. Vivian would marry for a second time by 1945, which may account for why her daughter, Donna, aged five, would be living with Irene at the time of the rock-falling incidents. Audrey was with her mother and stepfather in 1940, but war work may have meant she needed to stay with her grandmother as well.

The war was certainly having an effect not he family, as it was on all of Oakland—there was a huge housing crunch and influx of people to work in the Oakland shipyards. Irene, who was trained as a nurse, may have been doing some war work; Thomas, Irene’s husband, was working for the war department at Ft. Mason. (His 1942 draft card has him living in Berkeley, and gives as his emergency contact information a family member in Florida, not Irene.) Mike Hosier had joined the military in December of 1942. A gunner in the Pacific, he was reported to be hospitalized on 10 August 1943, at the time nine-year-old Audrey was with her grandmother. (Two years later, Audrey would be killed when she rode her bike into a car driven by a navy seaman while living in Santa Cruz.) At the time of the mysterious showers, though, she would have been living with a grandmother, a cousin twice-over, and worried about her injured biological father. It could not have been easy.

Whatever was going on the house at the time—and there’s no indication that the newspapers got it all correct, and I, writing from three-quarters-of-a-century later, using fragmentary documents definitely do not have a good grasp on events—the story of the sone falls did make capture attention. The Tribune wrote about it; so did the Chronicle. Boucher and de Ford made each other’s acquaintance over the matter. Later, a publication by Manly Hall Palmer, the occultist, and a Theosophical magazine would comment on the events, as would Steiger. And Joseph Henry Jackson used the news story as a peg for another article on Fort.

This one appeared 1 September 1943, in the Chronicle.

”So stones have been falling from nowhere in Oakland!

“Not so many years ago stones fell from nowhere in Chico. On the records are showers of stones—some even inside closed rooms—dropping all over the globe, in Scotland, in India, in Alabama, like stars falling. Newspapers cover the story each time; the police investigate; it’s bad boys somewhere behind the next house, out of sight. And the stones go on falling.

“Perhaps you read yesterday’s Chronicle story of latest developments in, around and upon the house of Mrs. Irene Fellows. If you did, and happened to be a reader of the works of Charles Fort, you were particularly interested. For Mr. Fort, during his lifetime, collected and wrote about reports of just this kind—showers of stones, of mud, of periwinkles, red rains and black rains, little fishes deposited upon a Surrey farm, odd ‘explosions’ (noises anyway), water dripping from the ceiling of a room in dry weather. The Chronicle reporter, in fact, mentioned one of the books of Mr. Fort, his ‘Wild Talents,’ in connection with the case of Grandma Fellows.

“Charles Fort: even in his lifetime (he died in 1932), was not widely read, in spite of the efforts of a group of interested citizens to promote his books. But his writings are available now in one volume, ‘The Books of Charles Fort’ (Henry Holt; $4.00), with an introduction by Tiffany Thayer, one of the most active loving spirits in the Fortean Society.

“And this seems as good a time as any, perhaps better than most, to remind you of Fort and his writing, and to introduce him, maybe to some who haven’t yet come across him.

“The Indefatigable Clip-Collector

“On the surface, Charles Fort was simply a man with a curious taste for collecting clippings from newspapers and periodicals, provided the stories related to unexplained happenings.

“Underneath, Fort was much more than this. He was no mere crank. He had as sound a purpose in doing what he did as any of the scientists about whom he enjoyed being so skeptical.

“His purposes, and those of the Fortean Society, are epitomized by Mr. Thayer in his introduction to ‘The Books of Charles Fort.’ What Fort was after was to remove the halo from the head of science to make people think; to destroy, if possible, the faith of scientists in their own works, thus compelling a general return to the truly scientific principle of ‘temporary acceptance.’

“To help in accomplishing these ends, Fort wrote four books, all of which are incorporated in one volume: ‘Wild Talents,’ ‘Lo!’ ‘New Lands’ and ‘The Book of the Damned.’ He wrote them, as Thayer once said, with a charred redo tree on the face of a cliff. This is to say, Fort wrote with a fine sense of exaggeration—exaggeration with a purpose. He flung words about magnificently. He indulged his Gargantuan sense of humor as he pleased. He juggle paradoxes and played games with words—even with sentence structure. But one thing he didn’t play with. He never made fun of ideas. To Fort, an idea (provided you didn’t say that the idea was the one and only truth) was the whole purpose of living and thinking. Ideas—new ideas about old things—were what he wanted to stimulate.

“Are Falling Stones ‘Teleportation’?

“But to come back to falling stones.

“Fort examined all sorts of curious occurrences. In the matter of stones and other substances ‘falling from the sky,’ however, he suggested (tongue in cheek, if you like) a theory of ‘teleportation.’ . . .

“Note that Fort doesn’t say ‘I think this is so.’ He never does that. He only suggests that he’s tired of tales about naughty boys, or whirlwinds carefully selecting frogs from a pond and including no mud or tadpoles; he’s tired of science smugly saying: ‘Oh, nonsense’ to any solutions but its own.

“But you’d better read him. Wile you’re reading you won’t be sure if you’re on your head or your heels. But then Fort knew that. He wrote to shake up his reader. He does. And the time to read him is when a story like that of Grandma Fellows and her rock-shower is fresh in your mind.”