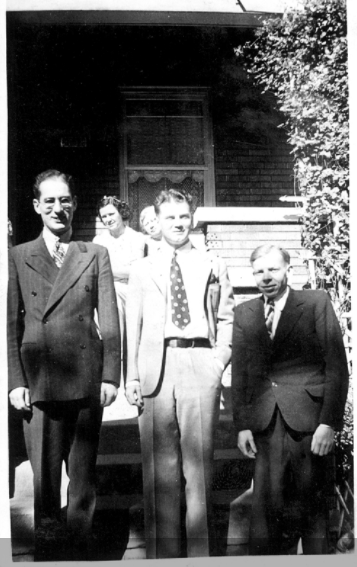

Julius Schwartz, Otto Binder, and Ray Palmer, 1938.

Julius Schwartz, Otto Binder, and Ray Palmer, 1938. He was vast—he contained multitudes—and only one small part was Fortean.

Raymond Alfred Palmer was born 1 August 1910 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, to Roy Clarence and the former Helena Martha Anna Steber. He would later fetishize his birth year, suggesting that he had seen Haley’s comet while still in utero, though in his memory he was held by his grandmother and shown the comet out the window. It is tempting to suggest, though no doubt too pat, that Palmer’s nostalgia was a reaction to what was otherwise a difficult childhood in many ways. The elder Palmer was a skilled laborer. In 1911, the family added a baby girl. Palmer was famously beautiful as a youngster, honored on a milk carton as one of Milwaukee’s healthiest babies. A brother would follow, in 1918, by which time Ray was suffering much. (Another brother would be born around 1929.)

When he was seven, Ray was in an accident with a truck that badly damaged his spine. Operations would follow, pain, and a slow recovery that was never complete: he was left a hunchback and short, never growing more than about four feet tall. Amid his convalescence, Ray’s mother died; Ray resented his father, blaming him for slow medical treatment, for drinking too much and tomcatting around. Unable to go to school, Palmer—who had learned to read very young—escaped into books, and especially the newly developing genre of science fiction. By his own admission, Palmer was a fanciful child, and there is every reason to believe that the line, for him, between reality and imagination was incredibly thin; fantastic literature was a natural fit.

Raymond Alfred Palmer was born 1 August 1910 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, to Roy Clarence and the former Helena Martha Anna Steber. He would later fetishize his birth year, suggesting that he had seen Haley’s comet while still in utero, though in his memory he was held by his grandmother and shown the comet out the window. It is tempting to suggest, though no doubt too pat, that Palmer’s nostalgia was a reaction to what was otherwise a difficult childhood in many ways. The elder Palmer was a skilled laborer. In 1911, the family added a baby girl. Palmer was famously beautiful as a youngster, honored on a milk carton as one of Milwaukee’s healthiest babies. A brother would follow, in 1918, by which time Ray was suffering much. (Another brother would be born around 1929.)

When he was seven, Ray was in an accident with a truck that badly damaged his spine. Operations would follow, pain, and a slow recovery that was never complete: he was left a hunchback and short, never growing more than about four feet tall. Amid his convalescence, Ray’s mother died; Ray resented his father, blaming him for slow medical treatment, for drinking too much and tomcatting around. Unable to go to school, Palmer—who had learned to read very young—escaped into books, and especially the newly developing genre of science fiction. By his own admission, Palmer was a fanciful child, and there is every reason to believe that the line, for him, between reality and imagination was incredibly thin; fantastic literature was a natural fit.

Palmer did graduate from a Catholic high school, in 1928, and started to move through science fiction circles, though he was leery of others, self-conscious about his deformity. He wrote some stories, and corresponded with other fans, finding their names and addresses in the letters section of Hugo Gernsback’s magazines. While working at a sheet metal factory in Chicago, Palmer started what is acknowledged to be the first science fiction fan club. He sent out the first fanzine, titled (appropriately enough) “The Comet,” in May 1930. That year, though, his mangled spine was infected with tuberculosis, and he was forced to spend two years in a sanatorium. His parents’s marriage was also on the rocks; they would separate in the middle of the decade.

Released, Palmer returned to work, doing bookkeeping but also manual work. And he continued his science fiction evangelizing. He was part of the Milwaukee Fictioneers—a group that competed with the Allied Authors to which belonged arch-Fortean and fellow-Milwaukee resident Fredric Brown—Palmer’s group including the likes of Robert Bloch (later author of “Psycho”) and Roger Sherman Hoar (pseudonym: Ralph Milne Farley). Throughout the 1930s, he was a dynamo within science fiction fandom, helping to organize it, giving a model to others, and maintaining the network of connections. In 1938, he became a professional editor: Gernsback had lost control of “Amazing Stories,” and it had fallen on hard times; the publisher hired Palmer to resurrect it.

And Palmer did. He used racier covers. He found upcoming writers—he was the first to publish Isaac Asimov, and also published Ray Bradbury and the Binder brothers. Palmer favored space operas. The magazine was clearly still behind the standard being set by “Astounding,” but it had its fans, and its readers. As “Amazing Stories” did better, Palmer was given more magazines to manage, and so nurtured a stable of writers upon whom he could rely. Among them was himself: Palmer would become a profligate writer under a vast number of pseudonyms—he contained multitudes!—some of which still haven’t been unmasked. He also began experimenting with a new variation on science fiction, in which authors speculated on ancient mysteries.

Palmer married Marjorie Wilson on Christmas Day 1942; their first child was born on Christmas Day 1943. They would have two more, a pair of girls born first, and then a boy. (Marjorie’s sister would write for “Amazing Stories.”) Unable to go to war, Palmer displayed his patriotism in the stories he chose to publish. One issue was devoted to stories only by military members. But one of the authors was killed in a bombing. And Ray’s younger brother, David, died in the Battle of the Bulge—1945. He was not even thirty. He was well-known about Chicago. The later skeptic Martin Gardner says he met him a few times, as did some of his friends: “He impressed us all as a shy, kind, good-natured, gentle, energetic little man with the personality of a professional con artist. He may have been slightly paranoid in the pleasure he got from his endless flimflams, but I think his primary motive was simply to create uproars that would sell magazines.” I a later article, based on hearsay testimony, Gardner said that Palmer’s middle initial—he signed himself as Raymond A. Palmer, or RAP—stood for nothing, and when he was challenged was so unsure of Palmer’s truth-telling that he refused to change his mind unless he saw a birth certificate.

“Amazing Stories” took just as the war was coming to an end, and continuing into the immediate post-War years, with what came to be known as the “Shaver Mystery.” A laborer from Pennsylvania, who had spent some time in a mental institution, wrote to Palmer about the earth’s secret history and long-standing battle between the Teros, as ancient and advanced race of earthlings—and the dears, or “detrimental robots,” which lived underground and controlled humans’s fates through rays. Palmer became fascinated, and started turning Shaver’s letters into stories—which found great interest in readers of the magazine, even as science fiction fans scoffed at the stories and the mythology that developed around them. It was a particularly potent mixing of “speculation” and ancient mysteries. And by the end of the decade, Palmer’s magazine would be dominated by such writing.

The story of the Shaver Mystery is vast, contradictory, and beyond the scope of what I am trying to do here. The point is, though, that Palmer presented these stories as telling truths, nonetheless, about the real state of the world. He had Shaver write more, and other authors contribute to the developing mythos, until the point that the magazine was mostly devoted to Shaver—and circulation numbers climbed. There were bits of Theosophy mixed in here, and renegade archeology, mysterious disappearances (explained as kidnappings by Deros); hollow earth theories; science fiction tropes in the form of “rays” and possible visitors from space—Palmer pushed stories that looked an awful lot like flying saucer tales even before the UFO craze hit in mid-1947. Of course, once flying saucers became a topic of discussion, they were simply folded into the Shaver Mystery: it was syncretic, and Palmer shoved a number of ideas into it. As Palmer’s biographer Fred Nadis puts it, “Palmer’s development of the Shaver Mystery provided a meeting place for the fantastic visions of science fiction and the separate but oddly similar components of occultist narratives.”

There was, however, a contingent of fans unhappy with the too-obvious occultism in science fiction—this was contested cultural territory, after all, and part of the contest was over just how much, just how straightforward, the occultism could be. Walter Gillings’s Fantasy Review reported, “A meeting of the Queens (New York) Science Fiction League solemnly passed a resolution expressing the opinion that the Shaver ‘Cave’ stories actually endangered the sanity of their readers, and bringing the menace to the notice of the Society for the Suppression of Vice. A fan conference in Philadelphia discussed a proposal that a 1,000 -signature petition be organised to get the offending magazines banned by the Post Office; but this project did not meet with approval, although speakers were unanimous in denouncing the Shaver Mythos as paranoic.”

As vocal science fiction fans bemoaned “Amazing Stories” transformation into a paranormal outlet, the magazine’s publisher, Ziff-Davis, planned a move of its editorial offices from Chicago to New York—a move that Palmer was unwilling to make, meaning he was scheduled to lose his job. The Shaver Mystery dropped out “Amazing Stories”. (Palmer blamed the turmoil on Deros.) During the kerfuffle, Shaver had also been working for another publisher, editing the true-tales-of-the-paranormal magazine “Fate,” under the pseudonym Robert N. Webster. Along with his “Amazing Stories” and the men’s magazine “True,” “Fate” helped to launch the flying saucer industry, giving the subject a secure place in American culture. Meanwhile, the magazine also covered all manner of paranormal ideas: ghosts, cryptozoology, telepathy, teleportation, reincarnation and the like. Nadis called it “National Geographic for explorers of the anomalous or weird.”

No longer at Ziff-Davis, publisher of “Amazing Stories,” Palmer focused on “Fate.” Palmer used some of the same techniques he had in his science fiction editorial work, gracing “Fate” with racy covers and trying to create an interactive network of fans. (The subscription list had come from the Fortean Wing Anderson.) He continued to blend fact and fiction, but from the other side now: whereas the Shaver Mystery had been fictional tales communicating real truths, “Fate” printed ostensibly non-fictional stories that told of fantastic, impossible things. He had a new central organizing object, too—Anderson had introduced Palmer to the Oahspe, the so-called spiritualist Bible. Palmer was fascinated. The magazine mentioned it frequently, and there were always advertisements selling it.

In 1949, Palmer and his family bought a farm in Amherst, Wisconsin. In 1950, he suffered an accident—Palmer blamed the Deros again—breaking his back again and almost dying. Recovered once more, though even more disabled, he, Marjorie, and the children moved to Amherst. He was still editing some science fiction magazines, and working with “Fate,” but was being pushed out there by his partners. At the same time, he was opening a publishing house—he would put out his own edition of Oahspe. And nearby lived Richard Shaver and his wife, invited to Wisconsin by Palmer. by the mid-1950s, Palmer was only tenuously connected to the science fiction community. Rather, his publishing house put out books on flying saucers and contactees, and he was publishing the magazine “Mystic,” which dwelt on paranormal topics. But, again, as Nadis notes, he tried to replicate the fan culture in these new ventures, helping to hold together what John Keel would later call the flying saucer subculture.

Through 1960s, Shaver moved farther into the fringes, his succession of publishing ventures—indulging in speculation about flying saucers and the paranormal—of smaller circulation and poorer quality. His politics, always focused on individual non-conformity—drifted to the right until, like John W. Campbell, he supported George Wallace. Palmer remained paranoid of lager structures and institutions, hidden or patent. A grand old man of science fiction, he earned some honors, as he suffered increasingly bad health. He continued his vexatious mixing of fiction and fact—sure some flying saucer pictures might be fake, he said, but they got people thinking factually—in his magazines and in the retrospectives he wrote.

Raymond Palmer died, after an operation for a blocked artery in his neck, on 15 August 1977. He had just turned 67.

*************

I am not sure when Ray Palmer read Fort, or heard about the Fortean Society; given his investment in science fiction from the 1920s, it was likely very early on, and repeatedly. Neither have I done a complete survey of all of his writings—even those known to be by him, since he used so many pseudonyms—and so cannot say whether or not there were stray references to Fort scattered about. Admitting all of that, it seems that Fort became important to him with the on-set of the Shaver Mystery, and continued to be throughout his exploration of fringe science, not so much as evidence or a model for how to research, but as support: Palmer absorbed Fort, and repurposed him.

Many Forteans, of course, were aware of Palmer, as they were closely tied to the science fiction community. Walter Dunkelberger, one of the early fanzine editors and Forteans, defended Palmer at first, for example, arguing that the Shaver Mystery stories made good reading, even if one was inclined not to believe them. But he eventually got fed up with Palmer’s refusal to be pinned down and demanded he take a stand: did he believe the Mystery or not? In the the summer of 1946, Robert L. Farnsworth set his own publication—“Rockets”—and his version of science fiction and Forteanism against the likes of Palmer’ Amazing Stories (and John W. Campbell’s Astounding, too). His was “the last stronghold of realistic, analytical thought, he said. Meanwhile, he claimed (incorrectly) that John W. Campbell was using the pseudonym George O. Smith in “Astounding” and Palmer was writing the Shaver material (that was often true), making science fiction and scientific speculation monotonous.

Palmer and the Shaver Mystery were especially intriguing to those Forteans already interested in metaphysical speculation, and so both the editor and his magazine were mentioned more than a few times by Vincent Gaddis and N. Meade Layne in “Round Robin”—which had grown out of the Theosophical family of metaphysical religions, and would stump for the idea that space ships traveled through the ether—from other planets and other dimensions—by altering their density. (This idea would, in some ways, be reborn in John Keel’s much later UFOlogy as demonology.) Layne’s ideas were developed in concert with his mediumistic “control” Mark Probert, who spoke to spirits of the dead in trances.

Gaddis wrote about the Shaver Mystery in the May-June 1947 issue of Round Robin, published by Layne’s Borderlands Science Research Association. As I wrote in my post on Gaddis:

“The Shaver Mystery was “one of the greatest puzzles of our time,” he wrote, suggesting that bound up in it were the answers to many esoteric, occult, and psychic questions. He had no doubt Shaver was honest, he told the readers, having been to Palmer’s offices in Chicago and seen Shaver’s pictures of the rays. He then assembled a vast array of sources proving the existence of inhabited prehistoric tunnels (he took these from Fortean writer Harold T. Wilkins and the Theosophical archives as well as the fictional book “Lost Horizons”); that the beings were powerful (shown, he said, by Ouspensky). He wasn’t sure, though, whether the being were physical or astral—if physical, maybe they were the remnants of Atlantis or Lemuria. If astral, perhaps N. Meade Layne’s speculations about visitors traveling through the ether by controlling their density were correct. That they were harmful was without doubt. He pointed to cases of spontaneous combustion (what were called pyrotics in Doubt) to suggest that people were being attacked. War was coming, civilization unraveling—he pointed to the sociologist Pirim Sorokin and the book “Generation of Vipers,” as evidence. Celestial beings may be watching. The Shaver Mystery—not the disappearance of Christ—was the clue that would explain these dark times.”

That same issue saw Layne’s speculations on the matter, “Dero-Queero Again—and the Spiritistic Interpretation.” In March 1948, Layne noted the coming-into-being of “Fate,” and remarked on the matter of Fate and UFOs in July. In 1951, Layne mused on the links between flying saucers and Shaver’s caverns. And his book on “Ether Ships”—a summa of his thoughts on UFOs—mentioned OAHSPE, which interest he may have picked up from Palmer.

That “Fate” should come to the attention of Forteans no surprise: since Palmer and Curtis had gotten their mailing list from Wing Anderson (who published OAHSPE), a Fortean, it makes sense the list would include a number of Forteans. Plus, there were plenty of science fiction Fortean interested to see what Palmer would do next. And, indeed, Fate did become the glossiest, biggest-circulation Fortean magazine, continuing even after Thayer died, and Doubt with him. It’s still produced now. Thayer mentioned its appearance in Doubt 21 (JUNE 1948). Under the heading “New Mag”—and just after he had discussed science fiction and its connection to Forteanism—Thayer wrote, “Your local newsdealer can supply you with FATE, a quarterly which appears to be a new property of the Palmer-Shaver crowd in Chicago. The first editorial bull, signed by Robert N. Webster, takes a high moral tone. We hope the magazine lives up to it.” He noted that Gaddis had several articles in it, and OAHSPE was advertised on its back cover, connecting the spiritualist Bible with Wing Anderson.

Thayer’s hopes soon enough appeared to be dashed—this was the common cycle for him—and he distanced himself from “Fate,” though—uncommonly for him—not publicly. He was irritated by an article in the third issue, by Frederick Clouser, on Charles Fort; Thayer told Don Bloch (who had liked the article), “This ‘author’ rewrote selected paragraphs from the Introduction to the Books and called it an article. I wish some of them would dig up something new.” He then dismissed the magazine itself, “Fate is published by Palmer, the Astounding man who gave Shaver to a gaping world.” Two years later, when Eric Frank Russell reported selling an article to Fate, Thayer first explained to him “Webster is Palmer. Yes.” And then wanted to make sure Russell was preserving the distance between Fate and the Fortean Society: “I just hope the piece you sold him does not mention the Society. We will never willingly be named in FATE.”

Indeed, Palmer and his acolytes seem to be partially responsible for a dustup within the Society, as Thayer continued to draw the line between his forms of Forteanism and other variants. For a time, he had played with the idea of starting Fortean chapters in various cities, but suddenly soured on it and lectured the chapters in Doubt that they had no support from the Society itself. San Francisco Forteans had thought they were responsible—for an exchange of letters in Fate, as it happened—and they may be partially right (especially since their activities involved Fate), but Thayer suggested there were more general problems with the Chapters, including those in Chicago, associated with the Shaver Mystery, or supportive of Palmer:

“The Chicago group was less responsible for the lecture to Chapters than some of the others, but the Shaver influence was in it. Otherwise sensible people have made a fetish of that nonsense, and they, together with table-tippers, can dominate a gathering, both groups hooting PREJUDICE, CLOSED MINDS, at us if we scoff. I’m finding it quite a trick to form axiomata generalia (so to speak), precedents which are not laws, ties which do not bind, quite a trick.”

Meanwhile Ray Palmer was absorbing Fort into his own metaphysical system, sometimes as himself, sometimes using other personas. Writing as RAP in “Amazing Stories” from June 1948, Palmer ended his monthly editorial, “Recently we introduced a prominent newspaperman to Charles Fort’s books, and ever since his aviation column has been full of spaceships. Charles Fort should be alive today—he’d have a picnic . . . and aren’t we all!” Really, this brief mention served as a tease for a later article in the issue, “Fortean Aspects of the Flying Disks.” The essay was attributed to Marx Kaye, and some commenters think of the name as a pseudonym for the science fiction writer S. J. Byrne. In truth, it was a house pseudonym, Everett F. Bleiler has noted, and there is no reason to believe that Byrne wrote this essay. Rather, it has all the hallmarks of being a Palmer production.

The article began, “Are the flying discs [NB: the article and title spelled the word disk differently] the product of another world?” It was an early statement of the so-called Extra-Terrestrial Hypothesis. Kaye then answered himself: “Before snickering at the question, the reader is requested to wade through the formidable but thought-awakening _Books of Charles Fort_,” and laid out its logic: If the flying saucers are new, then maybe they are some experimental human technology, a new plane or weapon; but if they are not new, then they must be of extra-terrestrial origin. (It wasn’t exactly air-tight logic.) The article then moved sidewise, to argue that people often could not believe their own eyes when it came to seeing the unexpected: systems of thought determine what people believe to be possible. And so scientistic mavericks such as Galileo and Pasteur (and, presumably, UFOlogists) were ridiculed.

Kaye follows up these rhetorical maneuvers by asserting that the disks are not the issue of nature, or the imaginings of dreamers, but natural facts. Which is where Fort enters the argument again: Kaye insists that Fort’s Super-Sargasso Sea is the center of a vortex, and out of this sometimes fall substances, raining onto the earth. As an example, Kaye points to unusual aerial phenomena over the Midwest in 1947 (Palmer lived in the Midwest, but Byrne lived in California.) “And contemporaneous with all this—flying discs.” Fort, Kaye noted, though extra-terrestrial visitors might hover in the Super-Sargasso. Why, though, would the flying saucers seem to increase their appearances now—they had visited the earth for a long time, but now there was a frenzy? Here Kaye gave the conventional response: atomic explosions had attracted the aliens’s interest. Ultimately, he thought that it was a good thing the aliens were appearing now, whether they were friendly or martial, because they would force humankind to recognize their shared nature and overcome petty national disputes to “unite against the dangers of the great Unknown . . .”

That same year, 1948—an annus mirabilis, of sorts, for Palmer, the year that Fate debuted, too—also saw him publishing a book of two Shaver novellas, the original “I Remember Lemuria” and “The Return of Sathanas.” The book was dotted with footnotes to Fort’s books, Fort’s collection of anomalies put to new uses, supporting Shaver’s (and Palmer’s) hollow earth speculations and wildly revisionist history. Many of the citations were passing; in one case, Shaver (or Palmer) attempted to use a typographic error as meaningful: “I don't know what significance, if any, is in the spelling of "extraordin-RAY," but that is the precise way it is spelled on page 909, THE BOOKS of CHARLES FORT.” (Indeed, that solecism is there on the page.) One especially long footnote showed just how Fort was repurposed:

“Disappearances—Slavery

The author is convinced that there have been many writers in the past and the present who either knew or suspected the existence of the caverns beneath the surface of the Earth, or that there was a power or a force or a race that was influencing the human race, usually for evil. The numerous legends of evil spirits, and good ones, too, tales of strange happenings, and strange disappearances. Charles Fort was one of those who came closest to guessing, or knowing the mysteries contained in the artificial cave world beneath the Earth’s surface. He thought that we were ‘fished for’, or that the possibility existed that we were fished for. For what purpose?

“Our facts are still intangible on this count to say for certain whether we are really fished for at the present day. But in the centuries part there were races such as the Jotuns, trading in living humans—as slaves (or food?)—might they not still be extant? Before the reader dismisses this question with ‘ridiculous!’ ;et him read any of the daily papers of the past few years, or The Books of Charles Fort for literally thousands of unexplained ‘disappearances’. People seen one moment and never again—even in the larger cities that are presumably well guarded.

“If the reader lives near any of the country’s large cities, he might call the Missing Persons’ Bureau, if any, and get the local statistics on the annual number of disappearances that are not accounted for, or the number undetected. Then, figure out how many larger cities there are in the whole nation—Author.”

Science fiction fans were not impressed with Palmer turning to Fort for support—it didn't make the Shaver Mystery (or its associations, including flying saucer speculations) more palatable. Reviewing the book for Walter Gillings’s “Fantasy Review,” Alan Devereaux noted,

“To give an air of credibility to fiction by presenting it as though it were recorded fact is one of the stock tricks of fantasy writers, which is legitimate enough; the reader enters into the spirit of the thing knowing that it isn’t really true, but wouldn’t it be fun if it were? Mr. Shaver, on the other hand, ably assisted by Mr. Palmer, tries to cram his stuff into his readers’ throats and wash it down with a liberal dose of Charles Fort, and by so doing he destroys the illusion completely for such sceptics as myself. I should like to think, none the less, that he was doing it with his tongue in his cheek. If, as he seems to insist, he actually believes in these creations of his own imagination, one can only regard it as rather pathetic.”

In 1949, the annual science fiction was held in Cincinnati. Dubbed the “Cinvention,” it ran from 3-5 September. Palmer was there for a day—pleasantly surprised he wasn’t berated by the fans for Amazing Stories’s turn toward mystery-mongering—and met up with Rog Philips and two Forteans, Roy Lavender and Stan Skirvin: they discussed the Shaver Mystery and Fortean topics. Palmer had not only come to the attention of Forteans and absorbed Fort’s ideas into his own system, but was developing Thayer’s tendency to see newspapers as spreaders of propaganda, trapped by narrow speaking. (His complaints got him labeled a communist sympathizer.) Skirvin came away from the talk thinking that Palmer had explained away the Shaver Mystery as a grab for more sales and more money. Maybe Palmer even said something like that, and it would seem to gain traction with the Shaver Master dropping out of “Amazing Stories,” while “Fate” concentrated on wider fields of paranormal interest—but the era was just an interregnum, and Palmer would soon enough be back to Shaverism, albeit in publications of smaller and smaller circulation.

Not only did these smaller circulation magazines return to Shaverism, while also promoting flying saucers, they moved Palmer back toward the metaphysical speculations of N. Meade Layne. The February 1955 issue of “Mystic,” for example, had a profile of Layne’s spiritualist medium Mark Probert, and said that he was willing to contact discarnate with questions sent in by readers. There was room enough in Palmer’s ramshackle system for both etheric flying saucers and extra-terrestrial ones. The world was much weirder than anyone knew, when the line between imagination and reality was erased, and the products of mind sent out to populate the universe. Another Palmer publication, “Search,” returned to the links between Fort and Shaver. The February 1958 issue featured an article titled “Charles Fort’s Corroboration of the Shaver Mystery.” It was by Jim Wentworth.

Wentworth is an enigma in science fiction, though probably he shouldn’t be. His name only appeared in publications associated with Palmer. He wrote for “Search,” and for Palmer’s “Forum.” He was credited as the author of Palmer’s (kind-of) biography, “Giants in Those Days.” There’s a book of letters between him and Shaver. But there’s no other information on Wentworth. Almost certainly, the name was another pseudonym. (There’s a science fiction story from 1936 that has a character called Jim Wentworth.) There’s even a kind of tip of the cap—the way personal details in Kaye’s article revealed the author to be Palmer: yet another Palmer production, “Shavertron,” had a regular column written by Wentworth. It was called “RAP’s Corner.” That is, Raymond A. Palmer’s corner. Until some positive biographical information about Wentworth comes to light, it’s best to assume that he was Palmer.

The article was much more extensive than the one by Kaye, ten-and-a-half double-columned pages. The article started by noting that people continue to clamor for proof of the Shaver Mystery, and even after they are told to read the newspapers (the proof is supposedly obvious there) and listen to the testimony of witnesses. So, next one should consult the books of Charles Fort. “Slowly, slowly, a conversion is taking place. What is he reading that has brought about this amazing reversal?” The story of a victim of spontaneous combustion in 1869 Paris, for one. And another in 1907 Pittsburgh. And more such cases, one after another, followed by other mysterious deaths. Then there were the cases of hysterical fainting at a girls’s school. Even more deaths, and more fainting. These weren’t examples of mad gassers—as in Mattoon—Wentworth assured, because there was no noxious smells. Half-a-page of cases culled from Fort, one-and-a-half, two-and-a-half. Then came accounts of mysterious missiles, bullet holes without bullets.

“Fort must have known _something_ about the caves of the ancients is obvious from his writings,” Wentworth concluded, forgoing logic for emotional association. “For, how could he have investigated such forbidden subjects without learning forbidden facts? Then why was the underworld not discussed openly?” Fort was writing around facts he did not want to admit, the article suggested—at one point Fort is quoted as saying humans have been induced to suicide telepathically. “Telepathically?,” Wentworth asks. “The hero are said to operate wondrous mental machines—telaugs, or telepathic projectors—which cause hypnotic compulsions that can turn mild-mannered surface folk into murderers!” Wentworth then cites an article I have not seen—Shaver Mystery Magazine, vol. 3, no. 1, 1949, which claimed to explain Fort’s data as caused by deros rays and extraterrestrial meddling. “Possibly Fort desired to focus attention on the latter as he considered it a greater menace than the goings on below.”

Or perhaps something else, the writer continued, remaking Fort so that he was not a library “mole,” as Dreiser called him, but an explorer of the fantastic, a Cassandra for the modern Trojan War: For, he said, worked in London at a time “when the dero were running things their own way, with no tero interference . . . Perhaps Fort wished to preserve his own life, so pretended ignorance of what was going on and thus kept himself from being killed.” (Back in 1938, “True Mystic” magazine published “Death Was Their Shadow,” suggesting Fort and his publisher, Claude Kendall, both died under mysterious and suspicious circumstances.”)

Wentworth’s article then shifted to consider accounts of spontaneous combustion and mysterious missiles that occurred after Fort’s death—including one noted by Fortean H. T. Wilkins—before shifting back to a consideration of unaccountable deaths about which Fort wrote—but then added, to really widen the possibility of dero interference, that the underground race had a ray which could cause heart attacks. To these few reports was added a comment taken, again, from Shaver Mystery Magazine (this time volume 2.1, 1948): a reader said that he went to the Mystery Spot (a carnival attraction-cum-occult space operated by a Fortean) and felt dizzy and confused by the weird angles of the buildings built there. The letter writer suggested that the spot might be caused by deros. I have not seen the issue of the magazine, but I wonder if the letter writer was the Fortean Frederick G. Hehr. Wentworth also references a similar spot in Oregon—operated by another Fortean.

The article then lurches—it is choppy throughout—to a consideration of disappearances: another misfortune caused by the deros. These are examples of malevolent teleportation by the deros, repeating the argument—fi not the facts—used int he footnote to Shaver’s 1948 book. After pointing out that a large number of people go missing in Chicago, Wentworth mulls a report mentioned by Fort, but his immediate source is, once more, the Fortean writer H. T. Wilkins, who wrote up the account for “Fate” magazine in 1953. It concerned a couple in Bristol, England (1873), who said that the floor of their hotel room had gaped open and swallowed them, though they managed to escape through a window. Wentworth approvingly cited a letter from Shaver which pointed out that opening floors is a common trope in fairy tales, proof the elder race has some technology to perform this feat.

Appended to the end was a story told in a letter to Fate about a street car operator and what we would now recognize as a phantom hitchhiker. The driver let a woman onto the streetcar; she attacked him, biting his thumb, dislocating it—and then disappeared mysteriously. (As it happened, the letter was contributed by Dulcie Brown, a member of the Fortean Society.) For Wentworth—well, for Palmer—this was proof that deros sometimes leave their underground lair and walk among us. After the attack, she was teleported back t the realm of the deros. “Do you have a _better_ explanation,” the article concluded—leaving Fort well behind.

The same view of Fort (and more broadly Fortean) reports as evidence of Shaver’s mythos (and extraterrestrials) continued to inform Palmer’s writing throughout the end of his life. Palmer—writing as Wentworth—included the footnote from the 1948 book in the first volume of “Giants in the Earth”—which concluded Palmer’s late thoughts on his own life and the Shaver Mystery. Of course, there were Fortean reports scattered throughout Palmer’s various publications, too. In the mid-1960s, he put out “Forum,” which was something like a newsletter. A couple of issues from 1966 included news clippings and collections of anomalous reports from the newspapers

And in 1967, “Jim Wentworth,” wrote about Fort again; this time, though, he was not trying to draw parallels with the Shaver Mystery, but turned his attention upwards, and argued that Fort’s accounts gave evidence for the etheric view of flying saucers—though N. Meade Layne was not cited. The article was titled “If the Sky Ever Opened Up,” and ran in volume 2, number 33 (June 1967) on pages 12-15.

Jim Wentworth, if the sky ever opened up, forum june 1967, vol 2, no 33 pp 12-15:

“The number of different objects that have fallen from the sky are truly enormous. Even as Charles Fort made this discovery in his research, he must have gasped in amazement. Let us devote the next two paragraphs to a mere fraction of these items which appear in THE BOOKS OF CHARLES FORT:

Inanimate Objects: Stones-unknown seeds-pollen-snowflakes the size of saucers-artifacts-warm water-edible ‘manna’-large chunks of ice-powder-coal-showers of mud and hot stones-colored rain, snow and various-sized hailstones-flesh and blood-ashes-pebbles-gelatinous fungus.

Animate objects: Fish-frogs-snakes-crabs-a turtle-unclassified eels-insects-lizards-black worms-snails-toads-jelyfish-minnows.

But where do they come from, these diversified items? Fort suggested a source (jokingly?) which he called the Super-Sargasso Sea. This was an aerial region ‘in which gravitation is inoperative and is not governed by the square of the distance—quite as magnetism is negligible at a very short distance from a magnet.’

Objects raised from Earth’s surface are held there in suspension until//13//released, shaken down, by certain conditions. It would see that terrestrial storms is one.

But Fort’s explanation fails to erase the puzzlement of a furrowed brow.

Take the descent of fish, Although there are many instances of live fish falling, other accounts tell of dropped fish that were headless, mutilated and putrefying. How come?

Additional interesting falls are:

A gray, foot-long snake landed at a person’s feet during a heavy shower. It lay as if stunned, then came to life.

Living fish fell, not with disorder, but in a straight line.

Lizards descended on sidewalks in Montreal, Canada.

Warm water spewed down from a clear sky.

Little toads dropped from above for two days.

Stones fell, with uncanny slowness, around two small girls as they picked leaves from the ground.

Not at all uncommon are cases of slow descents. Objects, later found to be heavy, have fallen with astonishingly low velocity. Why? Why were they not smashed to pieces upon impact with the hard earth?

God question, but a bigger one—that of point of origin—continues to remain an exasperating mystery.

Charles Fort’s Super-Sargasso Sea cannot be taken seriously. Not in these modern times. An aerial region existing at a height of several miles that contained fish, ice chunks, powder, frogs, coal, mussels, etc, would not remain unknown. Not with our powerful scientific instruments, grounded and in orbiting artificial satellites.

Besides, how could frogs (for instance) fall to a depth of many miles and still live? The bitter coldness of our higher atmosphere alone would kill them, no matter how slow their descent.

One might suggest that they fell only a short distance from the sky. That they came originally from a pond and were scooped up by a whirlwind. But then there is the mater of segregation to be considered. For in the cases discussed by Fort, only the frogs—and nothing else—fell. No traces of accompanying mud or debris from the bottom of the pond. No twigs, leaves or floating vegetation from the pond’s surface. Only frogs.

So to my mind, Fort’s Super-Sargasso Sea hypothesis is ruled out.

What of other possible origins for the falls? Well, certainly one of the better ones if advanced in the book FLYING SAUCER PILGRIMAGE by Bryant and Helen Reeve. From page 168:

“Reality as a whole in ‘outer-//14//space exists in various bands or octaves of vibratory frequencies. The human or earth-man’s band of vibratory frequency presents only the manifestations of physical life or reality as we know them. But there are many bands of vibratory frequency frequency in out-space. These other bands of frequency are definite vibratory motions of energy representing different types of matter which go to make up other phases or [sic] reality and existence. Consciousness produces energy in many frequencies and modes of motion and with it creates the ‘matter’ or the ‘substance’ of things or activities which it is conscious of.

‘The great error of the human mind is its limited belief that matter or substance in the higher realms of life is vaporous, weightless and non-solid. Nothing is farther from the cosmic truth. Each vibratory frequency has its own reality of existence—that is, it is solid and real to those who live in that frequency.’

And: ‘The veils between the frequencies make some space-beings and their worlds of life invisible and intangible to each other and to us. Thus in outer-space there are both visible and invisible worlds, suns and planets. Awareness of any of them depends upon one’s “tune-in” ability.’

Now, is the ‘vibratory frequencies; the answer to the riddle of falling objects? When a hailstone the size of an elephant plummets down from a clear sky, does that signify that a condition occurred bearing some resemblance to the condition preceding an earthquake? And, therefore, does this explanation solve the following mysteries taken from THE BOOKS?

August 18, 1880. Millions of exhausted flies fell on the waterfront streets of Havre, France. Pilot boats came to dock blackened by the flies which were reported to have come from a point over the English Channel.

May 28, 1881. During a violent thunderstorm, tons of periwinkles rained down near the city of Worchester England. Fields and gardens on both sides of Cromer Gardens Road were widely covered for about a mile. Included were hermit crabs.

May, 1892. On the streets of Coalburg, Alabama, they fell. So many eels that alarm gripped the populace. Farmers carted them away for fertilizing material.

Summer, 1896. From a clear sky, hundreds of dead birds plunged onto the streets of Baton Rouge, La.

March, 1922. Exotic insects by the thousands fell on the slopes of the Alps. Alive, and resembling spiders, caterpillars and huge ants, they died quickly.

Could it be that another world (similar to ours in many ways, life//15// forms certainly included, but operating on a different vibratory rate) is the real origin of fallen objects? Is that where the above phenomena come from?

Returning briefly to FLYING SAUCER PILGRIMAGE, when Bryant Reeve was asked what was the most unforgettable thing he had learned on his pilgrimage, he mentioned these vital points:

Life in outer space exists in octaves of frequencies.

Outer space is not empty, but is filled with life, forms, color, and activities.

This emphatically includes great unseen civilizations and cultures.

Outer space is made up of worlds without end, which are not nebulous, but real, solid, factual and glorious to those with the necessary tune-in ability.

The entrance to these worlds is not through distance in light years, but via the ‘frequency elevator’, by the conversion of the frequency and mode of vibration of energy.

Even the editor of the publication, Ray Palmer, professes a belief in intelligent civilizations of PHYSICAL and MATERIAL worlds in our atmosphere.

Which has me asking, gentle reader, that you bear some thought to the following:

While strolling peacefully along a quiet city street some warm evening, you may (if conditions are just right) be pelted by a foot-long catfish and hail—as actually happened at Norfolk, Virginia in 1853.

Or, while hiking in the open country, you may be deluged by a shower of flesh and blood—as also happened for three minutes on a sunny cloudless day in Los Nutos Township, California, during the summer of 1869.

The evidence suggests that Palmer was a close reader of Fort—he found telling misprints, and could cite particular sentences. (The quote above is accurate.) But he was never convinced by Fort’s hypotheses—which were indeed jokes. He used Fort for his own purposes. And then explained Fort’s insights by claiming he was writing in a kind of code, or perhaps restraining himself—suggesting that Fort knew the truth of the Shaver Mystery, too, but would not voice it out of fear. It was a view that was extremely paranoid, and one that would feed into the more radical reworking of Fortean-inflected metaphysical theories of the 1970s.

Released, Palmer returned to work, doing bookkeeping but also manual work. And he continued his science fiction evangelizing. He was part of the Milwaukee Fictioneers—a group that competed with the Allied Authors to which belonged arch-Fortean and fellow-Milwaukee resident Fredric Brown—Palmer’s group including the likes of Robert Bloch (later author of “Psycho”) and Roger Sherman Hoar (pseudonym: Ralph Milne Farley). Throughout the 1930s, he was a dynamo within science fiction fandom, helping to organize it, giving a model to others, and maintaining the network of connections. In 1938, he became a professional editor: Gernsback had lost control of “Amazing Stories,” and it had fallen on hard times; the publisher hired Palmer to resurrect it.

And Palmer did. He used racier covers. He found upcoming writers—he was the first to publish Isaac Asimov, and also published Ray Bradbury and the Binder brothers. Palmer favored space operas. The magazine was clearly still behind the standard being set by “Astounding,” but it had its fans, and its readers. As “Amazing Stories” did better, Palmer was given more magazines to manage, and so nurtured a stable of writers upon whom he could rely. Among them was himself: Palmer would become a profligate writer under a vast number of pseudonyms—he contained multitudes!—some of which still haven’t been unmasked. He also began experimenting with a new variation on science fiction, in which authors speculated on ancient mysteries.

Palmer married Marjorie Wilson on Christmas Day 1942; their first child was born on Christmas Day 1943. They would have two more, a pair of girls born first, and then a boy. (Marjorie’s sister would write for “Amazing Stories.”) Unable to go to war, Palmer displayed his patriotism in the stories he chose to publish. One issue was devoted to stories only by military members. But one of the authors was killed in a bombing. And Ray’s younger brother, David, died in the Battle of the Bulge—1945. He was not even thirty. He was well-known about Chicago. The later skeptic Martin Gardner says he met him a few times, as did some of his friends: “He impressed us all as a shy, kind, good-natured, gentle, energetic little man with the personality of a professional con artist. He may have been slightly paranoid in the pleasure he got from his endless flimflams, but I think his primary motive was simply to create uproars that would sell magazines.” I a later article, based on hearsay testimony, Gardner said that Palmer’s middle initial—he signed himself as Raymond A. Palmer, or RAP—stood for nothing, and when he was challenged was so unsure of Palmer’s truth-telling that he refused to change his mind unless he saw a birth certificate.

“Amazing Stories” took just as the war was coming to an end, and continuing into the immediate post-War years, with what came to be known as the “Shaver Mystery.” A laborer from Pennsylvania, who had spent some time in a mental institution, wrote to Palmer about the earth’s secret history and long-standing battle between the Teros, as ancient and advanced race of earthlings—and the dears, or “detrimental robots,” which lived underground and controlled humans’s fates through rays. Palmer became fascinated, and started turning Shaver’s letters into stories—which found great interest in readers of the magazine, even as science fiction fans scoffed at the stories and the mythology that developed around them. It was a particularly potent mixing of “speculation” and ancient mysteries. And by the end of the decade, Palmer’s magazine would be dominated by such writing.

The story of the Shaver Mystery is vast, contradictory, and beyond the scope of what I am trying to do here. The point is, though, that Palmer presented these stories as telling truths, nonetheless, about the real state of the world. He had Shaver write more, and other authors contribute to the developing mythos, until the point that the magazine was mostly devoted to Shaver—and circulation numbers climbed. There were bits of Theosophy mixed in here, and renegade archeology, mysterious disappearances (explained as kidnappings by Deros); hollow earth theories; science fiction tropes in the form of “rays” and possible visitors from space—Palmer pushed stories that looked an awful lot like flying saucer tales even before the UFO craze hit in mid-1947. Of course, once flying saucers became a topic of discussion, they were simply folded into the Shaver Mystery: it was syncretic, and Palmer shoved a number of ideas into it. As Palmer’s biographer Fred Nadis puts it, “Palmer’s development of the Shaver Mystery provided a meeting place for the fantastic visions of science fiction and the separate but oddly similar components of occultist narratives.”

There was, however, a contingent of fans unhappy with the too-obvious occultism in science fiction—this was contested cultural territory, after all, and part of the contest was over just how much, just how straightforward, the occultism could be. Walter Gillings’s Fantasy Review reported, “A meeting of the Queens (New York) Science Fiction League solemnly passed a resolution expressing the opinion that the Shaver ‘Cave’ stories actually endangered the sanity of their readers, and bringing the menace to the notice of the Society for the Suppression of Vice. A fan conference in Philadelphia discussed a proposal that a 1,000 -signature petition be organised to get the offending magazines banned by the Post Office; but this project did not meet with approval, although speakers were unanimous in denouncing the Shaver Mythos as paranoic.”

As vocal science fiction fans bemoaned “Amazing Stories” transformation into a paranormal outlet, the magazine’s publisher, Ziff-Davis, planned a move of its editorial offices from Chicago to New York—a move that Palmer was unwilling to make, meaning he was scheduled to lose his job. The Shaver Mystery dropped out “Amazing Stories”. (Palmer blamed the turmoil on Deros.) During the kerfuffle, Shaver had also been working for another publisher, editing the true-tales-of-the-paranormal magazine “Fate,” under the pseudonym Robert N. Webster. Along with his “Amazing Stories” and the men’s magazine “True,” “Fate” helped to launch the flying saucer industry, giving the subject a secure place in American culture. Meanwhile, the magazine also covered all manner of paranormal ideas: ghosts, cryptozoology, telepathy, teleportation, reincarnation and the like. Nadis called it “National Geographic for explorers of the anomalous or weird.”

No longer at Ziff-Davis, publisher of “Amazing Stories,” Palmer focused on “Fate.” Palmer used some of the same techniques he had in his science fiction editorial work, gracing “Fate” with racy covers and trying to create an interactive network of fans. (The subscription list had come from the Fortean Wing Anderson.) He continued to blend fact and fiction, but from the other side now: whereas the Shaver Mystery had been fictional tales communicating real truths, “Fate” printed ostensibly non-fictional stories that told of fantastic, impossible things. He had a new central organizing object, too—Anderson had introduced Palmer to the Oahspe, the so-called spiritualist Bible. Palmer was fascinated. The magazine mentioned it frequently, and there were always advertisements selling it.

In 1949, Palmer and his family bought a farm in Amherst, Wisconsin. In 1950, he suffered an accident—Palmer blamed the Deros again—breaking his back again and almost dying. Recovered once more, though even more disabled, he, Marjorie, and the children moved to Amherst. He was still editing some science fiction magazines, and working with “Fate,” but was being pushed out there by his partners. At the same time, he was opening a publishing house—he would put out his own edition of Oahspe. And nearby lived Richard Shaver and his wife, invited to Wisconsin by Palmer. by the mid-1950s, Palmer was only tenuously connected to the science fiction community. Rather, his publishing house put out books on flying saucers and contactees, and he was publishing the magazine “Mystic,” which dwelt on paranormal topics. But, again, as Nadis notes, he tried to replicate the fan culture in these new ventures, helping to hold together what John Keel would later call the flying saucer subculture.

Through 1960s, Shaver moved farther into the fringes, his succession of publishing ventures—indulging in speculation about flying saucers and the paranormal—of smaller circulation and poorer quality. His politics, always focused on individual non-conformity—drifted to the right until, like John W. Campbell, he supported George Wallace. Palmer remained paranoid of lager structures and institutions, hidden or patent. A grand old man of science fiction, he earned some honors, as he suffered increasingly bad health. He continued his vexatious mixing of fiction and fact—sure some flying saucer pictures might be fake, he said, but they got people thinking factually—in his magazines and in the retrospectives he wrote.

Raymond Palmer died, after an operation for a blocked artery in his neck, on 15 August 1977. He had just turned 67.

*************

I am not sure when Ray Palmer read Fort, or heard about the Fortean Society; given his investment in science fiction from the 1920s, it was likely very early on, and repeatedly. Neither have I done a complete survey of all of his writings—even those known to be by him, since he used so many pseudonyms—and so cannot say whether or not there were stray references to Fort scattered about. Admitting all of that, it seems that Fort became important to him with the on-set of the Shaver Mystery, and continued to be throughout his exploration of fringe science, not so much as evidence or a model for how to research, but as support: Palmer absorbed Fort, and repurposed him.

Many Forteans, of course, were aware of Palmer, as they were closely tied to the science fiction community. Walter Dunkelberger, one of the early fanzine editors and Forteans, defended Palmer at first, for example, arguing that the Shaver Mystery stories made good reading, even if one was inclined not to believe them. But he eventually got fed up with Palmer’s refusal to be pinned down and demanded he take a stand: did he believe the Mystery or not? In the the summer of 1946, Robert L. Farnsworth set his own publication—“Rockets”—and his version of science fiction and Forteanism against the likes of Palmer’ Amazing Stories (and John W. Campbell’s Astounding, too). His was “the last stronghold of realistic, analytical thought, he said. Meanwhile, he claimed (incorrectly) that John W. Campbell was using the pseudonym George O. Smith in “Astounding” and Palmer was writing the Shaver material (that was often true), making science fiction and scientific speculation monotonous.

Palmer and the Shaver Mystery were especially intriguing to those Forteans already interested in metaphysical speculation, and so both the editor and his magazine were mentioned more than a few times by Vincent Gaddis and N. Meade Layne in “Round Robin”—which had grown out of the Theosophical family of metaphysical religions, and would stump for the idea that space ships traveled through the ether—from other planets and other dimensions—by altering their density. (This idea would, in some ways, be reborn in John Keel’s much later UFOlogy as demonology.) Layne’s ideas were developed in concert with his mediumistic “control” Mark Probert, who spoke to spirits of the dead in trances.

Gaddis wrote about the Shaver Mystery in the May-June 1947 issue of Round Robin, published by Layne’s Borderlands Science Research Association. As I wrote in my post on Gaddis:

“The Shaver Mystery was “one of the greatest puzzles of our time,” he wrote, suggesting that bound up in it were the answers to many esoteric, occult, and psychic questions. He had no doubt Shaver was honest, he told the readers, having been to Palmer’s offices in Chicago and seen Shaver’s pictures of the rays. He then assembled a vast array of sources proving the existence of inhabited prehistoric tunnels (he took these from Fortean writer Harold T. Wilkins and the Theosophical archives as well as the fictional book “Lost Horizons”); that the beings were powerful (shown, he said, by Ouspensky). He wasn’t sure, though, whether the being were physical or astral—if physical, maybe they were the remnants of Atlantis or Lemuria. If astral, perhaps N. Meade Layne’s speculations about visitors traveling through the ether by controlling their density were correct. That they were harmful was without doubt. He pointed to cases of spontaneous combustion (what were called pyrotics in Doubt) to suggest that people were being attacked. War was coming, civilization unraveling—he pointed to the sociologist Pirim Sorokin and the book “Generation of Vipers,” as evidence. Celestial beings may be watching. The Shaver Mystery—not the disappearance of Christ—was the clue that would explain these dark times.”

That same issue saw Layne’s speculations on the matter, “Dero-Queero Again—and the Spiritistic Interpretation.” In March 1948, Layne noted the coming-into-being of “Fate,” and remarked on the matter of Fate and UFOs in July. In 1951, Layne mused on the links between flying saucers and Shaver’s caverns. And his book on “Ether Ships”—a summa of his thoughts on UFOs—mentioned OAHSPE, which interest he may have picked up from Palmer.

That “Fate” should come to the attention of Forteans no surprise: since Palmer and Curtis had gotten their mailing list from Wing Anderson (who published OAHSPE), a Fortean, it makes sense the list would include a number of Forteans. Plus, there were plenty of science fiction Fortean interested to see what Palmer would do next. And, indeed, Fate did become the glossiest, biggest-circulation Fortean magazine, continuing even after Thayer died, and Doubt with him. It’s still produced now. Thayer mentioned its appearance in Doubt 21 (JUNE 1948). Under the heading “New Mag”—and just after he had discussed science fiction and its connection to Forteanism—Thayer wrote, “Your local newsdealer can supply you with FATE, a quarterly which appears to be a new property of the Palmer-Shaver crowd in Chicago. The first editorial bull, signed by Robert N. Webster, takes a high moral tone. We hope the magazine lives up to it.” He noted that Gaddis had several articles in it, and OAHSPE was advertised on its back cover, connecting the spiritualist Bible with Wing Anderson.

Thayer’s hopes soon enough appeared to be dashed—this was the common cycle for him—and he distanced himself from “Fate,” though—uncommonly for him—not publicly. He was irritated by an article in the third issue, by Frederick Clouser, on Charles Fort; Thayer told Don Bloch (who had liked the article), “This ‘author’ rewrote selected paragraphs from the Introduction to the Books and called it an article. I wish some of them would dig up something new.” He then dismissed the magazine itself, “Fate is published by Palmer, the Astounding man who gave Shaver to a gaping world.” Two years later, when Eric Frank Russell reported selling an article to Fate, Thayer first explained to him “Webster is Palmer. Yes.” And then wanted to make sure Russell was preserving the distance between Fate and the Fortean Society: “I just hope the piece you sold him does not mention the Society. We will never willingly be named in FATE.”

Indeed, Palmer and his acolytes seem to be partially responsible for a dustup within the Society, as Thayer continued to draw the line between his forms of Forteanism and other variants. For a time, he had played with the idea of starting Fortean chapters in various cities, but suddenly soured on it and lectured the chapters in Doubt that they had no support from the Society itself. San Francisco Forteans had thought they were responsible—for an exchange of letters in Fate, as it happened—and they may be partially right (especially since their activities involved Fate), but Thayer suggested there were more general problems with the Chapters, including those in Chicago, associated with the Shaver Mystery, or supportive of Palmer:

“The Chicago group was less responsible for the lecture to Chapters than some of the others, but the Shaver influence was in it. Otherwise sensible people have made a fetish of that nonsense, and they, together with table-tippers, can dominate a gathering, both groups hooting PREJUDICE, CLOSED MINDS, at us if we scoff. I’m finding it quite a trick to form axiomata generalia (so to speak), precedents which are not laws, ties which do not bind, quite a trick.”

Meanwhile Ray Palmer was absorbing Fort into his own metaphysical system, sometimes as himself, sometimes using other personas. Writing as RAP in “Amazing Stories” from June 1948, Palmer ended his monthly editorial, “Recently we introduced a prominent newspaperman to Charles Fort’s books, and ever since his aviation column has been full of spaceships. Charles Fort should be alive today—he’d have a picnic . . . and aren’t we all!” Really, this brief mention served as a tease for a later article in the issue, “Fortean Aspects of the Flying Disks.” The essay was attributed to Marx Kaye, and some commenters think of the name as a pseudonym for the science fiction writer S. J. Byrne. In truth, it was a house pseudonym, Everett F. Bleiler has noted, and there is no reason to believe that Byrne wrote this essay. Rather, it has all the hallmarks of being a Palmer production.

The article began, “Are the flying discs [NB: the article and title spelled the word disk differently] the product of another world?” It was an early statement of the so-called Extra-Terrestrial Hypothesis. Kaye then answered himself: “Before snickering at the question, the reader is requested to wade through the formidable but thought-awakening _Books of Charles Fort_,” and laid out its logic: If the flying saucers are new, then maybe they are some experimental human technology, a new plane or weapon; but if they are not new, then they must be of extra-terrestrial origin. (It wasn’t exactly air-tight logic.) The article then moved sidewise, to argue that people often could not believe their own eyes when it came to seeing the unexpected: systems of thought determine what people believe to be possible. And so scientistic mavericks such as Galileo and Pasteur (and, presumably, UFOlogists) were ridiculed.

Kaye follows up these rhetorical maneuvers by asserting that the disks are not the issue of nature, or the imaginings of dreamers, but natural facts. Which is where Fort enters the argument again: Kaye insists that Fort’s Super-Sargasso Sea is the center of a vortex, and out of this sometimes fall substances, raining onto the earth. As an example, Kaye points to unusual aerial phenomena over the Midwest in 1947 (Palmer lived in the Midwest, but Byrne lived in California.) “And contemporaneous with all this—flying discs.” Fort, Kaye noted, though extra-terrestrial visitors might hover in the Super-Sargasso. Why, though, would the flying saucers seem to increase their appearances now—they had visited the earth for a long time, but now there was a frenzy? Here Kaye gave the conventional response: atomic explosions had attracted the aliens’s interest. Ultimately, he thought that it was a good thing the aliens were appearing now, whether they were friendly or martial, because they would force humankind to recognize their shared nature and overcome petty national disputes to “unite against the dangers of the great Unknown . . .”

That same year, 1948—an annus mirabilis, of sorts, for Palmer, the year that Fate debuted, too—also saw him publishing a book of two Shaver novellas, the original “I Remember Lemuria” and “The Return of Sathanas.” The book was dotted with footnotes to Fort’s books, Fort’s collection of anomalies put to new uses, supporting Shaver’s (and Palmer’s) hollow earth speculations and wildly revisionist history. Many of the citations were passing; in one case, Shaver (or Palmer) attempted to use a typographic error as meaningful: “I don't know what significance, if any, is in the spelling of "extraordin-RAY," but that is the precise way it is spelled on page 909, THE BOOKS of CHARLES FORT.” (Indeed, that solecism is there on the page.) One especially long footnote showed just how Fort was repurposed:

“Disappearances—Slavery

The author is convinced that there have been many writers in the past and the present who either knew or suspected the existence of the caverns beneath the surface of the Earth, or that there was a power or a force or a race that was influencing the human race, usually for evil. The numerous legends of evil spirits, and good ones, too, tales of strange happenings, and strange disappearances. Charles Fort was one of those who came closest to guessing, or knowing the mysteries contained in the artificial cave world beneath the Earth’s surface. He thought that we were ‘fished for’, or that the possibility existed that we were fished for. For what purpose?

“Our facts are still intangible on this count to say for certain whether we are really fished for at the present day. But in the centuries part there were races such as the Jotuns, trading in living humans—as slaves (or food?)—might they not still be extant? Before the reader dismisses this question with ‘ridiculous!’ ;et him read any of the daily papers of the past few years, or The Books of Charles Fort for literally thousands of unexplained ‘disappearances’. People seen one moment and never again—even in the larger cities that are presumably well guarded.

“If the reader lives near any of the country’s large cities, he might call the Missing Persons’ Bureau, if any, and get the local statistics on the annual number of disappearances that are not accounted for, or the number undetected. Then, figure out how many larger cities there are in the whole nation—Author.”

Science fiction fans were not impressed with Palmer turning to Fort for support—it didn't make the Shaver Mystery (or its associations, including flying saucer speculations) more palatable. Reviewing the book for Walter Gillings’s “Fantasy Review,” Alan Devereaux noted,

“To give an air of credibility to fiction by presenting it as though it were recorded fact is one of the stock tricks of fantasy writers, which is legitimate enough; the reader enters into the spirit of the thing knowing that it isn’t really true, but wouldn’t it be fun if it were? Mr. Shaver, on the other hand, ably assisted by Mr. Palmer, tries to cram his stuff into his readers’ throats and wash it down with a liberal dose of Charles Fort, and by so doing he destroys the illusion completely for such sceptics as myself. I should like to think, none the less, that he was doing it with his tongue in his cheek. If, as he seems to insist, he actually believes in these creations of his own imagination, one can only regard it as rather pathetic.”

In 1949, the annual science fiction was held in Cincinnati. Dubbed the “Cinvention,” it ran from 3-5 September. Palmer was there for a day—pleasantly surprised he wasn’t berated by the fans for Amazing Stories’s turn toward mystery-mongering—and met up with Rog Philips and two Forteans, Roy Lavender and Stan Skirvin: they discussed the Shaver Mystery and Fortean topics. Palmer had not only come to the attention of Forteans and absorbed Fort’s ideas into his own system, but was developing Thayer’s tendency to see newspapers as spreaders of propaganda, trapped by narrow speaking. (His complaints got him labeled a communist sympathizer.) Skirvin came away from the talk thinking that Palmer had explained away the Shaver Mystery as a grab for more sales and more money. Maybe Palmer even said something like that, and it would seem to gain traction with the Shaver Master dropping out of “Amazing Stories,” while “Fate” concentrated on wider fields of paranormal interest—but the era was just an interregnum, and Palmer would soon enough be back to Shaverism, albeit in publications of smaller and smaller circulation.

Not only did these smaller circulation magazines return to Shaverism, while also promoting flying saucers, they moved Palmer back toward the metaphysical speculations of N. Meade Layne. The February 1955 issue of “Mystic,” for example, had a profile of Layne’s spiritualist medium Mark Probert, and said that he was willing to contact discarnate with questions sent in by readers. There was room enough in Palmer’s ramshackle system for both etheric flying saucers and extra-terrestrial ones. The world was much weirder than anyone knew, when the line between imagination and reality was erased, and the products of mind sent out to populate the universe. Another Palmer publication, “Search,” returned to the links between Fort and Shaver. The February 1958 issue featured an article titled “Charles Fort’s Corroboration of the Shaver Mystery.” It was by Jim Wentworth.

Wentworth is an enigma in science fiction, though probably he shouldn’t be. His name only appeared in publications associated with Palmer. He wrote for “Search,” and for Palmer’s “Forum.” He was credited as the author of Palmer’s (kind-of) biography, “Giants in Those Days.” There’s a book of letters between him and Shaver. But there’s no other information on Wentworth. Almost certainly, the name was another pseudonym. (There’s a science fiction story from 1936 that has a character called Jim Wentworth.) There’s even a kind of tip of the cap—the way personal details in Kaye’s article revealed the author to be Palmer: yet another Palmer production, “Shavertron,” had a regular column written by Wentworth. It was called “RAP’s Corner.” That is, Raymond A. Palmer’s corner. Until some positive biographical information about Wentworth comes to light, it’s best to assume that he was Palmer.

The article was much more extensive than the one by Kaye, ten-and-a-half double-columned pages. The article started by noting that people continue to clamor for proof of the Shaver Mystery, and even after they are told to read the newspapers (the proof is supposedly obvious there) and listen to the testimony of witnesses. So, next one should consult the books of Charles Fort. “Slowly, slowly, a conversion is taking place. What is he reading that has brought about this amazing reversal?” The story of a victim of spontaneous combustion in 1869 Paris, for one. And another in 1907 Pittsburgh. And more such cases, one after another, followed by other mysterious deaths. Then there were the cases of hysterical fainting at a girls’s school. Even more deaths, and more fainting. These weren’t examples of mad gassers—as in Mattoon—Wentworth assured, because there was no noxious smells. Half-a-page of cases culled from Fort, one-and-a-half, two-and-a-half. Then came accounts of mysterious missiles, bullet holes without bullets.

“Fort must have known _something_ about the caves of the ancients is obvious from his writings,” Wentworth concluded, forgoing logic for emotional association. “For, how could he have investigated such forbidden subjects without learning forbidden facts? Then why was the underworld not discussed openly?” Fort was writing around facts he did not want to admit, the article suggested—at one point Fort is quoted as saying humans have been induced to suicide telepathically. “Telepathically?,” Wentworth asks. “The hero are said to operate wondrous mental machines—telaugs, or telepathic projectors—which cause hypnotic compulsions that can turn mild-mannered surface folk into murderers!” Wentworth then cites an article I have not seen—Shaver Mystery Magazine, vol. 3, no. 1, 1949, which claimed to explain Fort’s data as caused by deros rays and extraterrestrial meddling. “Possibly Fort desired to focus attention on the latter as he considered it a greater menace than the goings on below.”

Or perhaps something else, the writer continued, remaking Fort so that he was not a library “mole,” as Dreiser called him, but an explorer of the fantastic, a Cassandra for the modern Trojan War: For, he said, worked in London at a time “when the dero were running things their own way, with no tero interference . . . Perhaps Fort wished to preserve his own life, so pretended ignorance of what was going on and thus kept himself from being killed.” (Back in 1938, “True Mystic” magazine published “Death Was Their Shadow,” suggesting Fort and his publisher, Claude Kendall, both died under mysterious and suspicious circumstances.”)

Wentworth’s article then shifted to consider accounts of spontaneous combustion and mysterious missiles that occurred after Fort’s death—including one noted by Fortean H. T. Wilkins—before shifting back to a consideration of unaccountable deaths about which Fort wrote—but then added, to really widen the possibility of dero interference, that the underground race had a ray which could cause heart attacks. To these few reports was added a comment taken, again, from Shaver Mystery Magazine (this time volume 2.1, 1948): a reader said that he went to the Mystery Spot (a carnival attraction-cum-occult space operated by a Fortean) and felt dizzy and confused by the weird angles of the buildings built there. The letter writer suggested that the spot might be caused by deros. I have not seen the issue of the magazine, but I wonder if the letter writer was the Fortean Frederick G. Hehr. Wentworth also references a similar spot in Oregon—operated by another Fortean.

The article then lurches—it is choppy throughout—to a consideration of disappearances: another misfortune caused by the deros. These are examples of malevolent teleportation by the deros, repeating the argument—fi not the facts—used int he footnote to Shaver’s 1948 book. After pointing out that a large number of people go missing in Chicago, Wentworth mulls a report mentioned by Fort, but his immediate source is, once more, the Fortean writer H. T. Wilkins, who wrote up the account for “Fate” magazine in 1953. It concerned a couple in Bristol, England (1873), who said that the floor of their hotel room had gaped open and swallowed them, though they managed to escape through a window. Wentworth approvingly cited a letter from Shaver which pointed out that opening floors is a common trope in fairy tales, proof the elder race has some technology to perform this feat.

Appended to the end was a story told in a letter to Fate about a street car operator and what we would now recognize as a phantom hitchhiker. The driver let a woman onto the streetcar; she attacked him, biting his thumb, dislocating it—and then disappeared mysteriously. (As it happened, the letter was contributed by Dulcie Brown, a member of the Fortean Society.) For Wentworth—well, for Palmer—this was proof that deros sometimes leave their underground lair and walk among us. After the attack, she was teleported back t the realm of the deros. “Do you have a _better_ explanation,” the article concluded—leaving Fort well behind.

The same view of Fort (and more broadly Fortean) reports as evidence of Shaver’s mythos (and extraterrestrials) continued to inform Palmer’s writing throughout the end of his life. Palmer—writing as Wentworth—included the footnote from the 1948 book in the first volume of “Giants in the Earth”—which concluded Palmer’s late thoughts on his own life and the Shaver Mystery. Of course, there were Fortean reports scattered throughout Palmer’s various publications, too. In the mid-1960s, he put out “Forum,” which was something like a newsletter. A couple of issues from 1966 included news clippings and collections of anomalous reports from the newspapers

And in 1967, “Jim Wentworth,” wrote about Fort again; this time, though, he was not trying to draw parallels with the Shaver Mystery, but turned his attention upwards, and argued that Fort’s accounts gave evidence for the etheric view of flying saucers—though N. Meade Layne was not cited. The article was titled “If the Sky Ever Opened Up,” and ran in volume 2, number 33 (June 1967) on pages 12-15.

Jim Wentworth, if the sky ever opened up, forum june 1967, vol 2, no 33 pp 12-15:

“The number of different objects that have fallen from the sky are truly enormous. Even as Charles Fort made this discovery in his research, he must have gasped in amazement. Let us devote the next two paragraphs to a mere fraction of these items which appear in THE BOOKS OF CHARLES FORT:

Inanimate Objects: Stones-unknown seeds-pollen-snowflakes the size of saucers-artifacts-warm water-edible ‘manna’-large chunks of ice-powder-coal-showers of mud and hot stones-colored rain, snow and various-sized hailstones-flesh and blood-ashes-pebbles-gelatinous fungus.

Animate objects: Fish-frogs-snakes-crabs-a turtle-unclassified eels-insects-lizards-black worms-snails-toads-jelyfish-minnows.

But where do they come from, these diversified items? Fort suggested a source (jokingly?) which he called the Super-Sargasso Sea. This was an aerial region ‘in which gravitation is inoperative and is not governed by the square of the distance—quite as magnetism is negligible at a very short distance from a magnet.’

Objects raised from Earth’s surface are held there in suspension until//13//released, shaken down, by certain conditions. It would see that terrestrial storms is one.

But Fort’s explanation fails to erase the puzzlement of a furrowed brow.

Take the descent of fish, Although there are many instances of live fish falling, other accounts tell of dropped fish that were headless, mutilated and putrefying. How come?

Additional interesting falls are:

A gray, foot-long snake landed at a person’s feet during a heavy shower. It lay as if stunned, then came to life.

Living fish fell, not with disorder, but in a straight line.

Lizards descended on sidewalks in Montreal, Canada.

Warm water spewed down from a clear sky.

Little toads dropped from above for two days.

Stones fell, with uncanny slowness, around two small girls as they picked leaves from the ground.

Not at all uncommon are cases of slow descents. Objects, later found to be heavy, have fallen with astonishingly low velocity. Why? Why were they not smashed to pieces upon impact with the hard earth?

God question, but a bigger one—that of point of origin—continues to remain an exasperating mystery.

Charles Fort’s Super-Sargasso Sea cannot be taken seriously. Not in these modern times. An aerial region existing at a height of several miles that contained fish, ice chunks, powder, frogs, coal, mussels, etc, would not remain unknown. Not with our powerful scientific instruments, grounded and in orbiting artificial satellites.

Besides, how could frogs (for instance) fall to a depth of many miles and still live? The bitter coldness of our higher atmosphere alone would kill them, no matter how slow their descent.