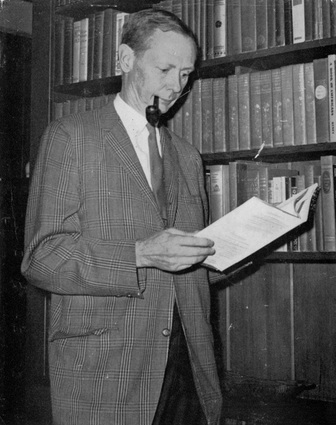

A behind-the-scenes Fortean.

William Milligan Sloane was born 15 August 1906, in Plymouth, Massachusetts. This was the year that Charles Fort started collecting reports of anomalous events, and so he was born into a Fortean universe. His mother was the former Julia L. Moss; his father Joseph C. Sloane. (In some documents, the surname was also spelled Sloan, with the E.) In 1910, according to the census, the family lived in Pottstown, Pennsylvania, where Joseph taught at The Hill School, a boarding school. Julia had only recently given birth to a second son, Joseph Jr. They rented their house, living with two servants as well as Joseph Senior’s sister, Hannah Spare.

The family continued peripatetic. At some point they moved to Illinois—Julia had family in the state; it was there, in 19115, that Julia drew up a will. They then continued westward, landing in the Los Angeles area toward the end of the decade. There were six of them, Julia in a book about their California life, “The Smiling Hill-Top”: Joseph and her, the two boys (Billie and Joe), and their twin Yorkshire terriers, Rags and Tags. The plan was to tay only a year, in a remote house overlooking the ocean once owned by own of Julia’s aunts, but they settled, and eventually found their way into Pasadena. That first part, when they lived on the hilltop, Joseph worked in town, apparently still teaching, and, because of the commute, only returning home on the weekends.

William Milligan Sloane was born 15 August 1906, in Plymouth, Massachusetts. This was the year that Charles Fort started collecting reports of anomalous events, and so he was born into a Fortean universe. His mother was the former Julia L. Moss; his father Joseph C. Sloane. (In some documents, the surname was also spelled Sloan, with the E.) In 1910, according to the census, the family lived in Pottstown, Pennsylvania, where Joseph taught at The Hill School, a boarding school. Julia had only recently given birth to a second son, Joseph Jr. They rented their house, living with two servants as well as Joseph Senior’s sister, Hannah Spare.

The family continued peripatetic. At some point they moved to Illinois—Julia had family in the state; it was there, in 19115, that Julia drew up a will. They then continued westward, landing in the Los Angeles area toward the end of the decade. There were six of them, Julia in a book about their California life, “The Smiling Hill-Top”: Joseph and her, the two boys (Billie and Joe), and their twin Yorkshire terriers, Rags and Tags. The plan was to tay only a year, in a remote house overlooking the ocean once owned by own of Julia’s aunts, but they settled, and eventually found their way into Pasadena. That first part, when they lived on the hilltop, Joseph worked in town, apparently still teaching, and, because of the commute, only returning home on the weekends.

The boys were attended to by their mother and a nanny; their were also gardeners and chauffeurs and servants. They were living an upper middle-class existence, and constantly surprised by running into professed members of Southern California’s metaphysical community: even their servants practiced New Thought, and they would go the the Theosophical community in Point Loma to see plays. The boys were outside constantly, and nicely tanned, she said, resenting the coming of September and school in the city. Early on, Joseph and she took turns having serious illnesses, and these taught her the skills she needed to get servants and others to help with the necessaries.

Such as attending to their cow, Poppy, which she did in a desultory fashion. But Poppy, though she eventually dried up, bequeathed the family something even more substantial than milk: a new life. Joseph, she wrote, “being tired of Latin verbs, Greek roots, and dull scholars generally, took up some interesting laboratory work after we emigrated to California. Growing Bulgarian bacilli to make fermented milk that would keep us all perennially amiable while we grew to be octogenarians, was one thing, but when the company, lured by the oratory of a cheese expert, were beguiled into making cream cheese--just the sort of cheese that Lucullus and Ponce de Leon both wanted but did not find--our troubles began. The company is composed of one minister with such an angelic expression that no one can refuse to sign anything if he holds out a pen; one aviator with youth, exuberant spirits, and a New England setness of purpose; one schoolmaster--strong on facing facts and callous to camouflage, and one temperamental cheese man. (It turned out afterward, however, that the janitor could make the best cheese of them all.)”

Julia does not date the essays on her book—they read like letters home, actually—but we know that Joseph was president of Vitalait Laboratory no later than September of 1918, when he filled out his draft card. This was in Pasadena. As far as I can tell, Vitalait produced cultured milk products. Julia wrote, “Developing a cheese business is a good deal like conducting a love affair—it blows hot and cold in a nerve-racking way. It is "the Public." You never can tellabout the Public! Sometimes it wants small packages for a small sum, or large packages for more, but mostly, what it frankly wants is a large package for a small sum! Some dealers didn't like the trade-mark. It was changed. It then turned out that the first trade-mark was really what was wanted. Then the cheese man fell desperately ill, which was a calamity, as neither the Book of Common Prayer, an aeroplane, nor a Latin Grammar is what you need in such a crisis.”

Illness hit the Sloane family again, it seems, in 1919. On 30 September, Julia died. Charles Scribner’s Sons published her book the next month. Her will bequeathed Joseph with real estate worth $10,000, personal property worth $50,000, and an estate of less than $10,0000. The 1920 census had the Sloane men living in Pasadena with an English servant, Edith Graves. Joseph—he went by Curtis, I believe—was president of the Vitality Laboratory. He had a mortgage on his house.

Presumably, it was around this time that William Sloane moved back to Pottstown and attended the Hill School. (His brother would follow.) He graduated from there, and then attended Princeton, just as his father had. In yearbooks, he went by the name William Milligan III. I do not understand where the “III” came from, of there was some family tradition or if it was an affectation. He did some traveling at this time, returning from a European trip (via Antwerp) in September 1928. By accounts, Sloane graduated from Princeton in 1929, when he would have been 23. His brother graduated from Princeton with a BA in 1931, and MFA in 1934. He went on to become a professor of art history.

The 1930 census has William in New York City, sharing an apartment with a Cooper P. Benedict. Benedict was a classmate at Princeton. He worked for a soap distributor. Sloane was an assistant manager at a publishing company. I do not know which one, but the biography attached to his papers at Princeton University have him working as an editor at Longmans, Green & Co; managing at the Fitzgerald Publishing Company; and employed as an associate editor at Farrar & Rinehart during this period.

Sloane was interested in the various strands of pulp fiction—mysteries, science fiction, and weird tales. And it was during this period that he essayed a writing career. In 1931, he published the play “Runner in the Snow: A Play of the Supernatural in One Act” and “Back Home: A Ghost Play in One Act”; in 1932, the play “Crystal Clear”; “The Silence of God” in 1933: “Art for Art’s Sake” and “The Invisible Clue,” both 1934); and “Gold Stars for Glory” (1935). He then moved to novels, “To Walk the Night” (1937) and “The Edge of Running Water” (1939). These are rather obscure today, but they were well-regarded by other writers of fantastic fiction. The two stories showed a lot of similarities and clearly drew on his own history—the first, for example, is set at Princeton, during the homecoming game, attended by a pair of alums who were rooming together in New York City. (This first was based on a play, and is set up as a dialogue, all the action taking place in the past.) The second dealt with a much older man who was operating a laboratory in Maine, trying to build a radio that would allow him to communicate with his dead wife: echoes, then, of his own father, distorted to fantasy.

The tales are sure-handed and well constructed, if very similar to one another. “To Walk” has the better set-up; “The Edge” has the better pay-off. They both blend mystery, science fictions and Lovecraftian cosmic horror, but subsume it in character studies. “To Walk” focuses on the spontaneous combustion of a heretical astronomer, and the doings of his mysterious wife—who, it turns out, is a developmentally disabled woman possessed by a disembodied mind from some other part of the universe, or some other dimension. The mind has an awesome intellect and immense powers, but it surprised to learn of pleasures only knowable by living a limited human span. The second novel, about the man who is trying to communicate with his dead wife, has the (mad) scientist making a critical error: he does not build a spiritual transmitter, but rips a hole in the space-time continuum.

For whatever reason, Sloane then left writing behind, almost completely. His second novel was made into the 1941 horror film “The Devil Commands,” though. Otherwise, Sloane seems to have focused on his work in publishing. Biographical summaries of Sloane’s life have him marrying in 1929, the year he graduated from Princeton, but this does not seem correct: the 1930 census, which was enumerated in April of 1930, still had him as single. I have seen one report, though, that he married in 1930 in New Mexico—which is interesting because a key portion of “To Walk” takes place in that state. His wife was Julia (same name as his mother) Margaret Hawkins.

By 1940, according to the census, they lived in New York City, with their two children, a son named William and a daughter named Jessie. (They would go on to have a third child.) William was doing well, working 54 hours per week, 52 weeks per year, and pulling in $5,000 dollars. They rented their apartment on West 11th Street for $77 per month. It was around this time—1938—that Sloane moved to Henry Holt & Company. He was instrumental, in 1941, with Holt putting out the Fort omnibus edition. That was the year his father died, on 8 June.

With World War II, Sloane directed the Council on Books in Wartime, an American effort to spread democratic ideas, and which produced “Armed Services Edition” paperback books for overseas military personnel. he continued this work through the end, according to standard biographies of him (which, to be clear, are all quite brief). However, there are documents showing him traveling internationally on government planes as late as 1948. (This material likely refers to his time with the Visiting Committee of American Book Publishers.)

In 1946, he founded his own house, William Sloane Associates, which he continued until 1952, when he resigned to become editorial director at Funk & Wagnall’s Company. Around this time, he also joined the faculty at the Bread Loaf Writer’s Conference, a summer program at Middlebury College in Vermont. (His paternal grandfather was from Vermont.) He continued with the program until 1972. Later, His wife edited his lectures from these visits into “The Craft of Writing,” which was published in 1969. After Funk & Wagnall’s, Sloane moved to Rutgers University Press, in 1955, where he was director until his death. As part of his duties, he was associated with the Association of American University Presses. (Rutgers was a natural rival of Princeton, and so there must have been some angst, real or ironic, upon taking this job.)

In the mid-1950s, he become involved in the science fiction world again—this was a time when a lot of the earlier pulp stories were finding new homes in books, and a wider audience. “To Walk the Night” was reprinted as a Dell paperback in 1956. That same year, Dell also put out “The Edge of running Water” as a paperback, though under the title “The Unquiet Corpse.” The two novels would later be combined under the title “The Rim of the Morning,” first put out in 1964, then again in 2015. They would also have separate French editions in 1961 and 1962, respectively. Meanwhile, he edited two science fiction collections, “Space, Space, Space” (1953) and “Stories for Tomorrow” (1954). The latter included Sloane’s only known piece of short fiction, “Let Nothing You Dismay.” I have seen neither of these collections, though, so not his editorial comments or the short story itself.

William M. Sloane died 25 September 1974, barely a month after he turned 68. He left behind his wife, his three children, and his brother.

*******************

Exactly when and where William Sloane first confronted Charles Fort is not known, as is the case with many Forteans. But it is clear that he knew Fort himself, and not just the Society, which is not always the case. Of course, he had ample opportunity to find his way to the books, and was of an age—the same generation of Thayer, as it happens—to have read Fort’s books as they were published. He would have been thirteen when “Book of the Damned” appeared. At the time, he was living in southern California and, based on his mother’s accounts, exposed to its metaphysical community, which would have been aware of Fort. Sloane was in publishing in 1931, when the Fortean Society had its first meeting and was making the press—and so might have looked into the man himself then, if not before. And if he still had not discovered Fort then, it is likely he would have heard of the man (and the Society) in the 1930s, when he was clearly reading (and writing) fantastic fiction. And we know that he collected Fort’s books.

There are Fortean elements in both of Sloane’s novels, certainly, though these are fairly muted. In an introduction to the 2015 “Rim of the Morning,” Stephen King notes that the first book, “To Walk,” especially has Fortean overtones. I do not think that these are actually very striking—they are there, but subtle. The most obvious Fortean connection is that the astronomy professor dies of spontaneous combustion. His wife displayed “wild talents,” but these were because she was possessed by an alien intelligence, not because she was some kind of evolutionary sport. Otherwise, the books owe a lot more to Lovecraft and lock-roomed mysteries—both of which, themselves, were influenced by Fort. The idea that weird anomalies might be evidence of elder gods, or cosmic beings, is Lovecraftian, and also Fortean; the explanation for lock-roomed mysteries that turn on the anomalous are an invigoration of the genre by Fort—Anthony Boucher was one of those who used Fortean explanations to solve such set ups.

After Thayer restarted the Society in the mid-1930s, he was anxious to produce an omnibus edition of Fort’s four books, with an index. There were many difficulties. One was finding copies of the books to use—“Book of the Damned” had made a splash, but had come out a decade-and-a-half earlier; “Lo!” was also well known. But the other two were not, especially “New Lands.” “Publisher’s Weekly” noted: when editors “started getting together Fort’s books (they were originally published by Claude Kendall) it was interesting to discover that volumes were almost impossible to find. Books had been swiped from the collections of Aaron Sussman, William Sloane, Ray Healey and other Fort enthusiasts and it took months of advertising to get all four volumes together.”

Sloane was at Holt by the time the project was getting going, and he seems to have been instrumental in having his publisher put out the omnibus edition; though it was made clear, repeatedly, that the books were actually published by the Fortean Society, but with Holt doing all of the work. According to the letters I have seen in the Henry Holt archives, Sloane worked with Aaron Sussman, another founder of the Fortean Society, Thayer confidante, and publishing employee. A preliminary agreement was forged between Sussman, Thayer, and Sloane—for Holt—in July of 1940, with contracts sent out in September. They were signed in November. It was in the midst of this process that Thayer sent Sloane a membership card in the Fortean Society. The letter said it was “for the year 1941,” which is not quite clear, but in all cases I have seen, Thayer did not send out new cards each year, so he likely meant that Sloane joined the Society in 1941.

Proving that Sloane was indeed imbricated in the science fiction network, as well as the Fortean one, he had lunch with John W. Campbell, famous science fiction editor of “Astounding,” in October, to consider running advertising in its sister magazine “Unknown,” which published Eric Frank Russell’s Fortean novel “Sinister Barrier.” Thayer protested a bit, leery because “Unknown” was just a pulp—he wanted to aim higher—but understood that the magazine was part of Fort’s audience; Sloane assuaged him that the plan was just to run a few advertisements in the magazine, no big campaign, and he wasn’t even sure of that, given the way the magazine’s publisher sold advertising space to five magazines at once, when all Holt wanted was to run an ad in “Unknown.”

In November, Sloane had to deal with another Thayer-provoked problem. He read the proposed introduction, and saw that it would offend the text book division of Holt. Sloane wrote to Sussman: “I am sending you up Tiffany Thayer’s introduction for a quick glance before I write to him. Several things about this I think require a tactful hand. First of all no matter what Mr. Thayer thinks he cannot come out with all these extremely arbitrary statements about schools and churches unless he does it in such a way that our college and high school departments will not be on my neck for printing a thing of this sort. Secondly this introduction doesn’t do for Charles Fort enough of what should be done. Most of the best material in it comes from the middle onward and I would like to see a good deal more about Fort himself. I believe that if we want to get some good consideration of this book it is important to have the preface contain everything which can be reasonably said about Fort, since it is not likely that anyone is going to do a full length biography of him in the future. Do look this over again and give me a more detailed report than your telephone conversation about your own reaction to it. Think, too, about our other departments here. I’ll then write Thayer.”

As I wrote in my post on Sussman, he must have must have prevailed upon Thayer to tone down the introduction, at least somewhat. It still started out—in a very Hechtian way—with a list of readers who probably should set the book aside, and praised atheism, but there was a substantial amount on Fort as a person and a thinker, and Thayer called out those he disagreed with in relatively vague terms. Holt’s textbook division was apparently appeased. And the book received solid advertising, especially in the Saturday Review, with its connections to Sussman. Hecht, too, reviewed it. (Not all Forteans were happy, though, and the science fiction Anthony Boucher compared it unfavorably to the true Forteanism that Thayer displayed in his introduction to “Lo!”)

It was published 1 April 1941.

Holt remained involved with the book, which meant Sloane did, too, though they were acting only as agents of the Fortean Society, which made matters a bit confusing. The matter that most involved them was getting the books to England, which was difficult first with the war, and then with post-war trade restrictions. In 1943, N. V. Dagg tried to get out an English edition. He was associated with the publisher King, Littlewood & King, which agreed to import the books into England—at the time, it was necessary to have one publisher responsible for importing an American book.

I wrote in my post on Dagg, The evidence, such as it is, suggests that King, Littlewood & King did their job, at least early on—though not necessarily to good effect, and with an eye on its own bottom line. In July 1943, Dagg wrote to William Sloane at Henry Holt (which had published the Fort omnibus for the Fortean Society). Apparently, this was in response to a letter from June, but I have not found it in the Holt archives. Dagg notes that he has received all the books and made payment; he also worried about the effect of the war on sales and the exchange rate—but was willing to take a flyer and issue a British edition of the Books of Charles Fort. King, Littlewood & King had a sense of the American market, he implied, since it was selling a book on reincarnation there (at least when German U-boats let the supply ships through). All he wanted was assurance that he would then get first rights to each of Fort’s individual books. Sloane wrote back later that month, saying that Holt would consider working with King, Littlewood & King, but could only deal with the rights to the single volume. The old copyrights to each of Fort’s individual books were “extremely confused.” As it happened, nothing ever came of Dagg’s plan to issue a British version of Fort’s books.

Getting out the omnibus edition, under trying conditions, and having some sent to England, under even more such conditions, was a Fortean coup. Thayer ended up making Sloane an Honorary Life Member of the Fortean Society in honor of his work—that, in fact, may be why the 1941 membership card was sent to him. Belonging to that class of membership meant that Sloane never had to pay dues, or anything, and would continue to receive Doubt. It was also just about the end of his connection to the Society: in the beginning is the end: one measures a circle beginning anywhere.

Sloane was only mentioned once in the pages of “Doubt,” and that was in passing. “Doubt” 41 (July 1953) carried a column on new books of Fortean interest. One of these was “To The End of Time: The Best of Olaf Stapledon,” which was put out by Sloane’s then-employer Funk & Wagnall’s. Thayer noted that the man instrumental in seeing the volume published was Honorary Life Member William Sloane.

It is not difficult to imagine why Sloane had little connection with the Fortean Society, although, admittedly, it’s speculation. As his response to Thayer’s draft introduction strongly suggests, Sloane was not on board with Thayer’s political and cultural critique. He liked universities—he was a Princeton man and would go on to work at Rutgers. He served with the government during World War II. Thayer blasted schools, universities, and war. Whatever drew Sloane to Fort, it was not social critique.

Most likely, based on his writing, it was the imaginative reach of Fort, his pointing to anomalies and then offering—never quite seriously—preposterous alternative explanations: in the end, his novels did the same thing, presenting the reader with an anomaly, and then explaining them outrageously, before decorously drawing a curtain around the whole matter. Fort, at least in Sloane’s writing, pointed the way toward feelings of the sublime.

Fort was there, in Sloane’s writing, in the background; just as Sloane, too, worked behind the scenes. He made Fort’s writings widely available, but his actions hardly went noticed, and then he slipped away from the Society.

Such as attending to their cow, Poppy, which she did in a desultory fashion. But Poppy, though she eventually dried up, bequeathed the family something even more substantial than milk: a new life. Joseph, she wrote, “being tired of Latin verbs, Greek roots, and dull scholars generally, took up some interesting laboratory work after we emigrated to California. Growing Bulgarian bacilli to make fermented milk that would keep us all perennially amiable while we grew to be octogenarians, was one thing, but when the company, lured by the oratory of a cheese expert, were beguiled into making cream cheese--just the sort of cheese that Lucullus and Ponce de Leon both wanted but did not find--our troubles began. The company is composed of one minister with such an angelic expression that no one can refuse to sign anything if he holds out a pen; one aviator with youth, exuberant spirits, and a New England setness of purpose; one schoolmaster--strong on facing facts and callous to camouflage, and one temperamental cheese man. (It turned out afterward, however, that the janitor could make the best cheese of them all.)”

Julia does not date the essays on her book—they read like letters home, actually—but we know that Joseph was president of Vitalait Laboratory no later than September of 1918, when he filled out his draft card. This was in Pasadena. As far as I can tell, Vitalait produced cultured milk products. Julia wrote, “Developing a cheese business is a good deal like conducting a love affair—it blows hot and cold in a nerve-racking way. It is "the Public." You never can tellabout the Public! Sometimes it wants small packages for a small sum, or large packages for more, but mostly, what it frankly wants is a large package for a small sum! Some dealers didn't like the trade-mark. It was changed. It then turned out that the first trade-mark was really what was wanted. Then the cheese man fell desperately ill, which was a calamity, as neither the Book of Common Prayer, an aeroplane, nor a Latin Grammar is what you need in such a crisis.”

Illness hit the Sloane family again, it seems, in 1919. On 30 September, Julia died. Charles Scribner’s Sons published her book the next month. Her will bequeathed Joseph with real estate worth $10,000, personal property worth $50,000, and an estate of less than $10,0000. The 1920 census had the Sloane men living in Pasadena with an English servant, Edith Graves. Joseph—he went by Curtis, I believe—was president of the Vitality Laboratory. He had a mortgage on his house.

Presumably, it was around this time that William Sloane moved back to Pottstown and attended the Hill School. (His brother would follow.) He graduated from there, and then attended Princeton, just as his father had. In yearbooks, he went by the name William Milligan III. I do not understand where the “III” came from, of there was some family tradition or if it was an affectation. He did some traveling at this time, returning from a European trip (via Antwerp) in September 1928. By accounts, Sloane graduated from Princeton in 1929, when he would have been 23. His brother graduated from Princeton with a BA in 1931, and MFA in 1934. He went on to become a professor of art history.

The 1930 census has William in New York City, sharing an apartment with a Cooper P. Benedict. Benedict was a classmate at Princeton. He worked for a soap distributor. Sloane was an assistant manager at a publishing company. I do not know which one, but the biography attached to his papers at Princeton University have him working as an editor at Longmans, Green & Co; managing at the Fitzgerald Publishing Company; and employed as an associate editor at Farrar & Rinehart during this period.

Sloane was interested in the various strands of pulp fiction—mysteries, science fiction, and weird tales. And it was during this period that he essayed a writing career. In 1931, he published the play “Runner in the Snow: A Play of the Supernatural in One Act” and “Back Home: A Ghost Play in One Act”; in 1932, the play “Crystal Clear”; “The Silence of God” in 1933: “Art for Art’s Sake” and “The Invisible Clue,” both 1934); and “Gold Stars for Glory” (1935). He then moved to novels, “To Walk the Night” (1937) and “The Edge of Running Water” (1939). These are rather obscure today, but they were well-regarded by other writers of fantastic fiction. The two stories showed a lot of similarities and clearly drew on his own history—the first, for example, is set at Princeton, during the homecoming game, attended by a pair of alums who were rooming together in New York City. (This first was based on a play, and is set up as a dialogue, all the action taking place in the past.) The second dealt with a much older man who was operating a laboratory in Maine, trying to build a radio that would allow him to communicate with his dead wife: echoes, then, of his own father, distorted to fantasy.

The tales are sure-handed and well constructed, if very similar to one another. “To Walk” has the better set-up; “The Edge” has the better pay-off. They both blend mystery, science fictions and Lovecraftian cosmic horror, but subsume it in character studies. “To Walk” focuses on the spontaneous combustion of a heretical astronomer, and the doings of his mysterious wife—who, it turns out, is a developmentally disabled woman possessed by a disembodied mind from some other part of the universe, or some other dimension. The mind has an awesome intellect and immense powers, but it surprised to learn of pleasures only knowable by living a limited human span. The second novel, about the man who is trying to communicate with his dead wife, has the (mad) scientist making a critical error: he does not build a spiritual transmitter, but rips a hole in the space-time continuum.

For whatever reason, Sloane then left writing behind, almost completely. His second novel was made into the 1941 horror film “The Devil Commands,” though. Otherwise, Sloane seems to have focused on his work in publishing. Biographical summaries of Sloane’s life have him marrying in 1929, the year he graduated from Princeton, but this does not seem correct: the 1930 census, which was enumerated in April of 1930, still had him as single. I have seen one report, though, that he married in 1930 in New Mexico—which is interesting because a key portion of “To Walk” takes place in that state. His wife was Julia (same name as his mother) Margaret Hawkins.

By 1940, according to the census, they lived in New York City, with their two children, a son named William and a daughter named Jessie. (They would go on to have a third child.) William was doing well, working 54 hours per week, 52 weeks per year, and pulling in $5,000 dollars. They rented their apartment on West 11th Street for $77 per month. It was around this time—1938—that Sloane moved to Henry Holt & Company. He was instrumental, in 1941, with Holt putting out the Fort omnibus edition. That was the year his father died, on 8 June.

With World War II, Sloane directed the Council on Books in Wartime, an American effort to spread democratic ideas, and which produced “Armed Services Edition” paperback books for overseas military personnel. he continued this work through the end, according to standard biographies of him (which, to be clear, are all quite brief). However, there are documents showing him traveling internationally on government planes as late as 1948. (This material likely refers to his time with the Visiting Committee of American Book Publishers.)

In 1946, he founded his own house, William Sloane Associates, which he continued until 1952, when he resigned to become editorial director at Funk & Wagnall’s Company. Around this time, he also joined the faculty at the Bread Loaf Writer’s Conference, a summer program at Middlebury College in Vermont. (His paternal grandfather was from Vermont.) He continued with the program until 1972. Later, His wife edited his lectures from these visits into “The Craft of Writing,” which was published in 1969. After Funk & Wagnall’s, Sloane moved to Rutgers University Press, in 1955, where he was director until his death. As part of his duties, he was associated with the Association of American University Presses. (Rutgers was a natural rival of Princeton, and so there must have been some angst, real or ironic, upon taking this job.)

In the mid-1950s, he become involved in the science fiction world again—this was a time when a lot of the earlier pulp stories were finding new homes in books, and a wider audience. “To Walk the Night” was reprinted as a Dell paperback in 1956. That same year, Dell also put out “The Edge of running Water” as a paperback, though under the title “The Unquiet Corpse.” The two novels would later be combined under the title “The Rim of the Morning,” first put out in 1964, then again in 2015. They would also have separate French editions in 1961 and 1962, respectively. Meanwhile, he edited two science fiction collections, “Space, Space, Space” (1953) and “Stories for Tomorrow” (1954). The latter included Sloane’s only known piece of short fiction, “Let Nothing You Dismay.” I have seen neither of these collections, though, so not his editorial comments or the short story itself.

William M. Sloane died 25 September 1974, barely a month after he turned 68. He left behind his wife, his three children, and his brother.

*******************

Exactly when and where William Sloane first confronted Charles Fort is not known, as is the case with many Forteans. But it is clear that he knew Fort himself, and not just the Society, which is not always the case. Of course, he had ample opportunity to find his way to the books, and was of an age—the same generation of Thayer, as it happens—to have read Fort’s books as they were published. He would have been thirteen when “Book of the Damned” appeared. At the time, he was living in southern California and, based on his mother’s accounts, exposed to its metaphysical community, which would have been aware of Fort. Sloane was in publishing in 1931, when the Fortean Society had its first meeting and was making the press—and so might have looked into the man himself then, if not before. And if he still had not discovered Fort then, it is likely he would have heard of the man (and the Society) in the 1930s, when he was clearly reading (and writing) fantastic fiction. And we know that he collected Fort’s books.

There are Fortean elements in both of Sloane’s novels, certainly, though these are fairly muted. In an introduction to the 2015 “Rim of the Morning,” Stephen King notes that the first book, “To Walk,” especially has Fortean overtones. I do not think that these are actually very striking—they are there, but subtle. The most obvious Fortean connection is that the astronomy professor dies of spontaneous combustion. His wife displayed “wild talents,” but these were because she was possessed by an alien intelligence, not because she was some kind of evolutionary sport. Otherwise, the books owe a lot more to Lovecraft and lock-roomed mysteries—both of which, themselves, were influenced by Fort. The idea that weird anomalies might be evidence of elder gods, or cosmic beings, is Lovecraftian, and also Fortean; the explanation for lock-roomed mysteries that turn on the anomalous are an invigoration of the genre by Fort—Anthony Boucher was one of those who used Fortean explanations to solve such set ups.

After Thayer restarted the Society in the mid-1930s, he was anxious to produce an omnibus edition of Fort’s four books, with an index. There were many difficulties. One was finding copies of the books to use—“Book of the Damned” had made a splash, but had come out a decade-and-a-half earlier; “Lo!” was also well known. But the other two were not, especially “New Lands.” “Publisher’s Weekly” noted: when editors “started getting together Fort’s books (they were originally published by Claude Kendall) it was interesting to discover that volumes were almost impossible to find. Books had been swiped from the collections of Aaron Sussman, William Sloane, Ray Healey and other Fort enthusiasts and it took months of advertising to get all four volumes together.”

Sloane was at Holt by the time the project was getting going, and he seems to have been instrumental in having his publisher put out the omnibus edition; though it was made clear, repeatedly, that the books were actually published by the Fortean Society, but with Holt doing all of the work. According to the letters I have seen in the Henry Holt archives, Sloane worked with Aaron Sussman, another founder of the Fortean Society, Thayer confidante, and publishing employee. A preliminary agreement was forged between Sussman, Thayer, and Sloane—for Holt—in July of 1940, with contracts sent out in September. They were signed in November. It was in the midst of this process that Thayer sent Sloane a membership card in the Fortean Society. The letter said it was “for the year 1941,” which is not quite clear, but in all cases I have seen, Thayer did not send out new cards each year, so he likely meant that Sloane joined the Society in 1941.

Proving that Sloane was indeed imbricated in the science fiction network, as well as the Fortean one, he had lunch with John W. Campbell, famous science fiction editor of “Astounding,” in October, to consider running advertising in its sister magazine “Unknown,” which published Eric Frank Russell’s Fortean novel “Sinister Barrier.” Thayer protested a bit, leery because “Unknown” was just a pulp—he wanted to aim higher—but understood that the magazine was part of Fort’s audience; Sloane assuaged him that the plan was just to run a few advertisements in the magazine, no big campaign, and he wasn’t even sure of that, given the way the magazine’s publisher sold advertising space to five magazines at once, when all Holt wanted was to run an ad in “Unknown.”

In November, Sloane had to deal with another Thayer-provoked problem. He read the proposed introduction, and saw that it would offend the text book division of Holt. Sloane wrote to Sussman: “I am sending you up Tiffany Thayer’s introduction for a quick glance before I write to him. Several things about this I think require a tactful hand. First of all no matter what Mr. Thayer thinks he cannot come out with all these extremely arbitrary statements about schools and churches unless he does it in such a way that our college and high school departments will not be on my neck for printing a thing of this sort. Secondly this introduction doesn’t do for Charles Fort enough of what should be done. Most of the best material in it comes from the middle onward and I would like to see a good deal more about Fort himself. I believe that if we want to get some good consideration of this book it is important to have the preface contain everything which can be reasonably said about Fort, since it is not likely that anyone is going to do a full length biography of him in the future. Do look this over again and give me a more detailed report than your telephone conversation about your own reaction to it. Think, too, about our other departments here. I’ll then write Thayer.”

As I wrote in my post on Sussman, he must have must have prevailed upon Thayer to tone down the introduction, at least somewhat. It still started out—in a very Hechtian way—with a list of readers who probably should set the book aside, and praised atheism, but there was a substantial amount on Fort as a person and a thinker, and Thayer called out those he disagreed with in relatively vague terms. Holt’s textbook division was apparently appeased. And the book received solid advertising, especially in the Saturday Review, with its connections to Sussman. Hecht, too, reviewed it. (Not all Forteans were happy, though, and the science fiction Anthony Boucher compared it unfavorably to the true Forteanism that Thayer displayed in his introduction to “Lo!”)

It was published 1 April 1941.

Holt remained involved with the book, which meant Sloane did, too, though they were acting only as agents of the Fortean Society, which made matters a bit confusing. The matter that most involved them was getting the books to England, which was difficult first with the war, and then with post-war trade restrictions. In 1943, N. V. Dagg tried to get out an English edition. He was associated with the publisher King, Littlewood & King, which agreed to import the books into England—at the time, it was necessary to have one publisher responsible for importing an American book.

I wrote in my post on Dagg, The evidence, such as it is, suggests that King, Littlewood & King did their job, at least early on—though not necessarily to good effect, and with an eye on its own bottom line. In July 1943, Dagg wrote to William Sloane at Henry Holt (which had published the Fort omnibus for the Fortean Society). Apparently, this was in response to a letter from June, but I have not found it in the Holt archives. Dagg notes that he has received all the books and made payment; he also worried about the effect of the war on sales and the exchange rate—but was willing to take a flyer and issue a British edition of the Books of Charles Fort. King, Littlewood & King had a sense of the American market, he implied, since it was selling a book on reincarnation there (at least when German U-boats let the supply ships through). All he wanted was assurance that he would then get first rights to each of Fort’s individual books. Sloane wrote back later that month, saying that Holt would consider working with King, Littlewood & King, but could only deal with the rights to the single volume. The old copyrights to each of Fort’s individual books were “extremely confused.” As it happened, nothing ever came of Dagg’s plan to issue a British version of Fort’s books.

Getting out the omnibus edition, under trying conditions, and having some sent to England, under even more such conditions, was a Fortean coup. Thayer ended up making Sloane an Honorary Life Member of the Fortean Society in honor of his work—that, in fact, may be why the 1941 membership card was sent to him. Belonging to that class of membership meant that Sloane never had to pay dues, or anything, and would continue to receive Doubt. It was also just about the end of his connection to the Society: in the beginning is the end: one measures a circle beginning anywhere.

Sloane was only mentioned once in the pages of “Doubt,” and that was in passing. “Doubt” 41 (July 1953) carried a column on new books of Fortean interest. One of these was “To The End of Time: The Best of Olaf Stapledon,” which was put out by Sloane’s then-employer Funk & Wagnall’s. Thayer noted that the man instrumental in seeing the volume published was Honorary Life Member William Sloane.

It is not difficult to imagine why Sloane had little connection with the Fortean Society, although, admittedly, it’s speculation. As his response to Thayer’s draft introduction strongly suggests, Sloane was not on board with Thayer’s political and cultural critique. He liked universities—he was a Princeton man and would go on to work at Rutgers. He served with the government during World War II. Thayer blasted schools, universities, and war. Whatever drew Sloane to Fort, it was not social critique.

Most likely, based on his writing, it was the imaginative reach of Fort, his pointing to anomalies and then offering—never quite seriously—preposterous alternative explanations: in the end, his novels did the same thing, presenting the reader with an anomaly, and then explaining them outrageously, before decorously drawing a curtain around the whole matter. Fort, at least in Sloane’s writing, pointed the way toward feelings of the sublime.

Fort was there, in Sloane’s writing, in the background; just as Sloane, too, worked behind the scenes. He made Fort’s writings widely available, but his actions hardly went noticed, and then he slipped away from the Society.