I think I’ve got the right Fortean. A poetic lover of the anomalous, who was a stalwart member through the mid- and late-1940s, only to disappear.

I know this: his name is Walter H. Kerr, who served in the military during World War II. I know that because Thayer says so, Doubt 11 (winter 1944), page 154. He used the same first name—but no middle initial—in the previous issue. And otherwise called him Kerr, thirty-two times by my count, between the summer of 1944 and winter 1949—every issue between 10 and 27 except 13 and 26. (I have not seen issue 22, so don’t include it in my count, and it may be another one without Kerr’s name.) Twice Thayer included his clippings among the issue’s best. And Kerr wrote a poem in honor of the Fortean Society:

I know this: his name is Walter H. Kerr, who served in the military during World War II. I know that because Thayer says so, Doubt 11 (winter 1944), page 154. He used the same first name—but no middle initial—in the previous issue. And otherwise called him Kerr, thirty-two times by my count, between the summer of 1944 and winter 1949—every issue between 10 and 27 except 13 and 26. (I have not seen issue 22, so don’t include it in my count, and it may be another one without Kerr’s name.) Twice Thayer included his clippings among the issue’s best. And Kerr wrote a poem in honor of the Fortean Society:

“The song of the damned”

The poltergeist, this sly afreet, he

Cast an object, slightly sleety,

A cylinder, a bit concrete-y

From a cloudless sky.

The Army had no explanation,

And Pruett waived vague speculation,

But Thayer said, in vast elation,

‘This datum shall not die.

‘We doubt not that the sly jinn do it

But Ike will say that Joey threw it

And God knows what the Reverend Pruett

Will say to spread the lie?

‘Truth will out though they obscure it

In newsprint brief as it is lurid,

And concrete, abstract, ‘s not so pure it

Scorns the law of gravity.’

Then Pruett said, ‘I cannot see it,’

And the ‘Russian Hail,’ Ike said, ‘must be it,”

And all, I think, surely agree it

‘s not a diamond in the sky.

Astronomers soon were all nutty,

And all high brass committed suttee

To find a mixer, putty, putty,

Up above the world so high.

The inside story really wows us --

While earthbound red tape waits and drowses

The genie’s building Veterans’ houses

And his output’s high.

The genie puts his shoulder to it--

To hell with Ike, to hell with Pruett,

We’ll live in Heaven and commuett

By rocket by and by.

(Pruett was J. High Pruett, a science writer.)

So what else do I think I know about Kerr, and why do I think so? I believe that Kerr was born in Indiana on 21 June 1914. He was the son of Ada an Ezra Kerr, the latter a baker, and the oldest of three sons. [Who's who in U.S. Writers, Editors & Poets, 1988, 285] He moved to Washington, D.C., in 1931 to work at the Government Printing Office; he remained an employee there until the mid-1960s. By 1940, he had married the former Evelyn Henderson and was living with her, her sister, brother-in-law, parents, and a five year old boy of undetermined relationship, at 403 11th Street, SE. Kerr enlisted in the army 15 August 1942 . (He was 5’11’ and about 160) pounds. By that point, he was separated from his wife. Kerr served in Paris, where he decided to become a poet, according to his 1961 book of poetry, Populations of the Heart (p. 29).

Reading between the lines of Doubt, the Kerr who belonged to the Fortean Society also served in France. At least, in 1945 he sent in a clipping from Stars and Stripe, Paris edition. Later, he was in the Washington, D.C., area. And it is also clear that the Kerr who sent material to the Fortean Society was a student of prosody. Thus it is my conclusion that the Fortean Kerr was Walter Howard Kerr, who became something of a notable poet, and, indeed, wrote a number of science-fiction poems. I have not seen the most of them, so cannot say if they were Fortean inflected, but the science fiction connection alone is enough to add confidence to the identification of this obscure but active Fortean.

He published

?“Beads from a Broken Rosary” Imagi (1949)?

Four Poems in Voices (1951)

“Trap” “Prenatal Fantasy” “The Hanged Thing” “Vampire” “The Stone”, Fire and Sleet and Candlelight (1961)

Populations of the Heart (1961)

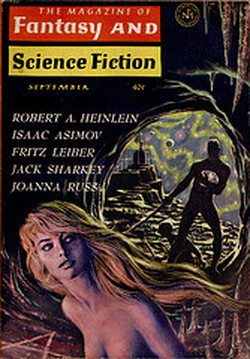

“Gruesome Discovery at the 242nd St. Feeding Station” Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (Feb. 1962)

“Communication” Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (Mar. 1962)

“The Mermaid in the Swimming Pool” Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (May 1962)

“Card Sharp” Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (Nov.1962)

“Amusement Park in Winter,” Southwest Review (1963)

“Starlesque” Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (Jun. 1963)

“Attrition” Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (Sep. 1963)

“Treat” Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (Nov.1964) [Reprinted in The Best from Fantasy and Science Fiction, 1966]

“Somo These Days” Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (Dec. 1964)

“Illusion” Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (Mar. 1965)

“From A Terran Travel Folder” Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (Feb. 1968)

“The Shade in the Old Apple Tree” The Arkham Collector (Winter 1971)

“In Intricate Magicks” The Arkham Collector (Summer 1971)

“In Dream” and “The Esrever Boys on Safari” Poetry (Dec. 1971)

“The Mad Old Man” Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (Mar. 1973)*

“Beneath to Yellow Mask of Morning” Cthullu Calls (Jan. 1976)* (“Trap” also appeared in this issue.)

Rye Bread: Women Poets Rising (19770. Edited with Stacy Tuthill.

Countdown to Bedlam: A Portfolio of Paranoiac Poems (1978) [includes poems marked with *.]

American Classic: Car Poems for Collectors (1985). Edited with Mary Swope.

All but one of his poems appeared after he was no longer referenced in Doubt, presumably because he had left the Fortean Society for one reason or another. It is hard to get a complete handle on his Forteanism, given the lack of information. Perhaps there is information in his papers, now housed at the University of Maryland; however, they have been unprocessed for a decade. In the meantime, the abundance of clippings gives an outline, at any rate. Apparently, he had a number of Fortean interests, among them some social critiques that paralleled Thayer’s.

Many of Kerr’s clippings referred to typical Forteana. He sent in material on an earthquake in New York, the Mattoon Bomber, and the Witch of Scrapfaggot [Doubt 11]. (Those last two stories will be covered later.) Other clippings referenced a chimney that was supposedly so weakened by the pecking of sparrows, a wind blew it down [Doubt 15], a frog and lizard dug up—alive—in 2,000,000 year-old rock [Doubt 17]; an alligator in Indiana [Doubt 18]; red tides and strange skeletons, the sinking of Welch, WV, and a leafless tree that had water mysteriously puddling beneath it [Doubt 20]; and three-toed tracks found on a Florida beach. [Doubt 21.] (That story will also be discussed some time in the future.) He seemed on the look-out for reports of Thayer’s pet anomalies: stray bullets [Doubt 15 and 17], spontaneous combustion (styled ‘pyrotics’) [Doubt 17], and alternative cancer cures [Doubt 20 and 23]. In 1948, Kerr sent some money in support to help in Society republish The Rational Non-Mystical Cosmos by George F. Gillette. (The Society’s plans fell through.)

Kerr also shared with Thayer a sense that the world was absurd, the people in charge confused—and possibly evil, which could trail off into a deep suspicion of authorities. Kerr sent in—and Thayer mocked—a report that there would be three to five million less ducks around Louisville, KY one year—as if there were someone out counting the ducks, Thayer sniffed. [Doubt 12]. Kerr and Thayer jointly mocked the theory of physicist P.A.M. Dirac that protons, neutrons, and electrons had mass but not size [Doubt 17]. They speculated that the Red Cross sold blood plasma that was donated to it [Doubt 18]. They thought modern medicine was screwy: that TB might not be contagious [Doubt 21] and that doctor’s might accidentally kill their patients, but other doctors would support them [Doubt 21]. And of course priests were seen as archaic authorities [Doubt 27].

This shared political bent led to an overlapping sense of humor. A box of food dropped from an airplane to feed starving, snowbound Navajos—another Fortean story which will be taken up later—landed on a woman and killed her, for example [Doubt 25]. And Kerr was one of two people to send in a classified ad from the Washington Times Herald, dated 28 January 1948, which should also be the subject of a later write-up. It read, “Anyone, anywhere, who saw a man become invisible eight years ago, on May 3, 1940, please write immediately to ……………., as an invisible man has been with me for almost eight years” [Doubt 21]. Kerr apparently looked up the advertiser—probably because he lived in the area—but nothing more was reported on the odd advertisement.

Two of Kerr’s more humorous contributions got him mentioned among the best clippings of the issue, in Thayer’s regular mock contest for “first prize.” In one, a banker at a professional banquet choked to death on a piece of steak [Doubt 25]. “What could be more poetic?,” Thayer asked. In another, an American military man found a gold ring on the Pacific island of New Britain, and sent it to his mother. The Chicago Tribune story suggested the original owner might have been eaten by cannibals. But what interested Thayer was a political irony. Inscribed on the ring was this: “Woodrow Wilson, 1913—28th President of the United States—1921. The professor. We desire no conquest, no dominion.”

But there was at least one subject upon which Kerr and Thayer disagreed: flying saucers. Kerr evinced an early interest in stories about lights in the sky. His first contribution was an article about such lights above Mexico, Missouri [Fortean Society Magazine 10]. And the rash of his material used in the subsequent issue—Doubt 11—included a clipping about a mysterious light seen above the Midwest. In 1946 came reports of strange lights seen above Sweden. Some though that they might be rockets fired by the Soviets, but other denials were more . . . unusual. Kerr found a story in which one report was explained away as a whistling clothesline [Doubt 17]. Kenneth Arnold’s report of objects over Mt. Rainier, Washington, in June 1947, kicked off the modern flying saucer movement, and Forteans demanded Thayer report on the issue. Among those seems to have been Kerr, who sent in many clippings on the topic [Doubt 19, 21, and 24]. Thayer did write these up, but grudgingly. He didn’t like the subject, at all.

As flying saucers became established in the fringe and Theosophical sciences, Thayer kept having to at least mention them, but Kerr left the Fortean Society. He was still working for the Government Printing Office. And was just beginning to get some of his poems published. His writing, though, wouldn’t take off until the 1960s, after Thayer and the Fortean Society both died. Exactly what he was up to during the 1950s and why he stopped contributing to the Society after years of dedicated membership are mysteries.

The poltergeist, this sly afreet, he

Cast an object, slightly sleety,

A cylinder, a bit concrete-y

From a cloudless sky.

The Army had no explanation,

And Pruett waived vague speculation,

But Thayer said, in vast elation,

‘This datum shall not die.

‘We doubt not that the sly jinn do it

But Ike will say that Joey threw it

And God knows what the Reverend Pruett

Will say to spread the lie?

‘Truth will out though they obscure it

In newsprint brief as it is lurid,

And concrete, abstract, ‘s not so pure it

Scorns the law of gravity.’

Then Pruett said, ‘I cannot see it,’

And the ‘Russian Hail,’ Ike said, ‘must be it,”

And all, I think, surely agree it

‘s not a diamond in the sky.

Astronomers soon were all nutty,

And all high brass committed suttee

To find a mixer, putty, putty,

Up above the world so high.

The inside story really wows us --

While earthbound red tape waits and drowses

The genie’s building Veterans’ houses

And his output’s high.

The genie puts his shoulder to it--

To hell with Ike, to hell with Pruett,

We’ll live in Heaven and commuett

By rocket by and by.

(Pruett was J. High Pruett, a science writer.)

So what else do I think I know about Kerr, and why do I think so? I believe that Kerr was born in Indiana on 21 June 1914. He was the son of Ada an Ezra Kerr, the latter a baker, and the oldest of three sons. [Who's who in U.S. Writers, Editors & Poets, 1988, 285] He moved to Washington, D.C., in 1931 to work at the Government Printing Office; he remained an employee there until the mid-1960s. By 1940, he had married the former Evelyn Henderson and was living with her, her sister, brother-in-law, parents, and a five year old boy of undetermined relationship, at 403 11th Street, SE. Kerr enlisted in the army 15 August 1942 . (He was 5’11’ and about 160) pounds. By that point, he was separated from his wife. Kerr served in Paris, where he decided to become a poet, according to his 1961 book of poetry, Populations of the Heart (p. 29).

Reading between the lines of Doubt, the Kerr who belonged to the Fortean Society also served in France. At least, in 1945 he sent in a clipping from Stars and Stripe, Paris edition. Later, he was in the Washington, D.C., area. And it is also clear that the Kerr who sent material to the Fortean Society was a student of prosody. Thus it is my conclusion that the Fortean Kerr was Walter Howard Kerr, who became something of a notable poet, and, indeed, wrote a number of science-fiction poems. I have not seen the most of them, so cannot say if they were Fortean inflected, but the science fiction connection alone is enough to add confidence to the identification of this obscure but active Fortean.

He published

?“Beads from a Broken Rosary” Imagi (1949)?

Four Poems in Voices (1951)

“Trap” “Prenatal Fantasy” “The Hanged Thing” “Vampire” “The Stone”, Fire and Sleet and Candlelight (1961)

Populations of the Heart (1961)

“Gruesome Discovery at the 242nd St. Feeding Station” Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (Feb. 1962)

“Communication” Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (Mar. 1962)

“The Mermaid in the Swimming Pool” Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (May 1962)

“Card Sharp” Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (Nov.1962)

“Amusement Park in Winter,” Southwest Review (1963)

“Starlesque” Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (Jun. 1963)

“Attrition” Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (Sep. 1963)

“Treat” Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (Nov.1964) [Reprinted in The Best from Fantasy and Science Fiction, 1966]

“Somo These Days” Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (Dec. 1964)

“Illusion” Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (Mar. 1965)

“From A Terran Travel Folder” Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (Feb. 1968)

“The Shade in the Old Apple Tree” The Arkham Collector (Winter 1971)

“In Intricate Magicks” The Arkham Collector (Summer 1971)

“In Dream” and “The Esrever Boys on Safari” Poetry (Dec. 1971)

“The Mad Old Man” Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (Mar. 1973)*

“Beneath to Yellow Mask of Morning” Cthullu Calls (Jan. 1976)* (“Trap” also appeared in this issue.)

Rye Bread: Women Poets Rising (19770. Edited with Stacy Tuthill.

Countdown to Bedlam: A Portfolio of Paranoiac Poems (1978) [includes poems marked with *.]

American Classic: Car Poems for Collectors (1985). Edited with Mary Swope.

All but one of his poems appeared after he was no longer referenced in Doubt, presumably because he had left the Fortean Society for one reason or another. It is hard to get a complete handle on his Forteanism, given the lack of information. Perhaps there is information in his papers, now housed at the University of Maryland; however, they have been unprocessed for a decade. In the meantime, the abundance of clippings gives an outline, at any rate. Apparently, he had a number of Fortean interests, among them some social critiques that paralleled Thayer’s.

Many of Kerr’s clippings referred to typical Forteana. He sent in material on an earthquake in New York, the Mattoon Bomber, and the Witch of Scrapfaggot [Doubt 11]. (Those last two stories will be covered later.) Other clippings referenced a chimney that was supposedly so weakened by the pecking of sparrows, a wind blew it down [Doubt 15], a frog and lizard dug up—alive—in 2,000,000 year-old rock [Doubt 17]; an alligator in Indiana [Doubt 18]; red tides and strange skeletons, the sinking of Welch, WV, and a leafless tree that had water mysteriously puddling beneath it [Doubt 20]; and three-toed tracks found on a Florida beach. [Doubt 21.] (That story will also be discussed some time in the future.) He seemed on the look-out for reports of Thayer’s pet anomalies: stray bullets [Doubt 15 and 17], spontaneous combustion (styled ‘pyrotics’) [Doubt 17], and alternative cancer cures [Doubt 20 and 23]. In 1948, Kerr sent some money in support to help in Society republish The Rational Non-Mystical Cosmos by George F. Gillette. (The Society’s plans fell through.)

Kerr also shared with Thayer a sense that the world was absurd, the people in charge confused—and possibly evil, which could trail off into a deep suspicion of authorities. Kerr sent in—and Thayer mocked—a report that there would be three to five million less ducks around Louisville, KY one year—as if there were someone out counting the ducks, Thayer sniffed. [Doubt 12]. Kerr and Thayer jointly mocked the theory of physicist P.A.M. Dirac that protons, neutrons, and electrons had mass but not size [Doubt 17]. They speculated that the Red Cross sold blood plasma that was donated to it [Doubt 18]. They thought modern medicine was screwy: that TB might not be contagious [Doubt 21] and that doctor’s might accidentally kill their patients, but other doctors would support them [Doubt 21]. And of course priests were seen as archaic authorities [Doubt 27].

This shared political bent led to an overlapping sense of humor. A box of food dropped from an airplane to feed starving, snowbound Navajos—another Fortean story which will be taken up later—landed on a woman and killed her, for example [Doubt 25]. And Kerr was one of two people to send in a classified ad from the Washington Times Herald, dated 28 January 1948, which should also be the subject of a later write-up. It read, “Anyone, anywhere, who saw a man become invisible eight years ago, on May 3, 1940, please write immediately to ……………., as an invisible man has been with me for almost eight years” [Doubt 21]. Kerr apparently looked up the advertiser—probably because he lived in the area—but nothing more was reported on the odd advertisement.

Two of Kerr’s more humorous contributions got him mentioned among the best clippings of the issue, in Thayer’s regular mock contest for “first prize.” In one, a banker at a professional banquet choked to death on a piece of steak [Doubt 25]. “What could be more poetic?,” Thayer asked. In another, an American military man found a gold ring on the Pacific island of New Britain, and sent it to his mother. The Chicago Tribune story suggested the original owner might have been eaten by cannibals. But what interested Thayer was a political irony. Inscribed on the ring was this: “Woodrow Wilson, 1913—28th President of the United States—1921. The professor. We desire no conquest, no dominion.”

But there was at least one subject upon which Kerr and Thayer disagreed: flying saucers. Kerr evinced an early interest in stories about lights in the sky. His first contribution was an article about such lights above Mexico, Missouri [Fortean Society Magazine 10]. And the rash of his material used in the subsequent issue—Doubt 11—included a clipping about a mysterious light seen above the Midwest. In 1946 came reports of strange lights seen above Sweden. Some though that they might be rockets fired by the Soviets, but other denials were more . . . unusual. Kerr found a story in which one report was explained away as a whistling clothesline [Doubt 17]. Kenneth Arnold’s report of objects over Mt. Rainier, Washington, in June 1947, kicked off the modern flying saucer movement, and Forteans demanded Thayer report on the issue. Among those seems to have been Kerr, who sent in many clippings on the topic [Doubt 19, 21, and 24]. Thayer did write these up, but grudgingly. He didn’t like the subject, at all.

As flying saucers became established in the fringe and Theosophical sciences, Thayer kept having to at least mention them, but Kerr left the Fortean Society. He was still working for the Government Printing Office. And was just beginning to get some of his poems published. His writing, though, wouldn’t take off until the 1960s, after Thayer and the Fortean Society both died. Exactly what he was up to during the 1950s and why he stopped contributing to the Society after years of dedicated membership are mysteries.