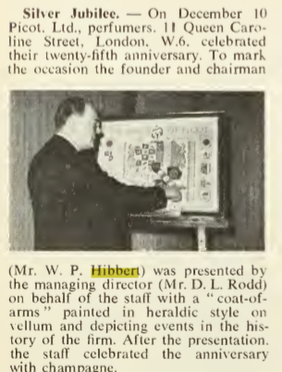

Wallace P. Hibbert (?), 1963, from "The Chemist and Druggist".

Wallace P. Hibbert (?), 1963, from "The Chemist and Druggist". A sweet smelling Fortean.

Too much? Perhaps. But I know so little.

There were actually two Forteans with the surname Hibbert mentioned in Doubt over the years—but I think I can separate them. E. M. G. Hibbert appeared only once. He was from New Zealand, and may have been associated with another Kiwi Fortean, Guy Powell. At least, they sent in aspects of the same story, about a bull’s brain cavity housing some kind of small animal. The other Hibbert lived in London and seems to have accounted for the vast bulk of the material attributed to that name. I know nothing more about E. M. G. Hibbert; I only know a little more about W. P. Hibbert.

W. P. Hibbert was almost certainly Wallace P(atrick?) Hibbert, born July 1912 in Barnet, a borough in Middlesex, part of northern London. He married Marjorie L. Coles. After World War II, the Hibberts were involved in the perfume business. Around April 1947, they joined with Raoul Pellegrin to form Cie de Dandon en Provence, which was engaged in buying and selling perfumes and related cosmetics. The company, addressed at Aldwych House, in London, had 100 pounds as starting capital.

Too much? Perhaps. But I know so little.

There were actually two Forteans with the surname Hibbert mentioned in Doubt over the years—but I think I can separate them. E. M. G. Hibbert appeared only once. He was from New Zealand, and may have been associated with another Kiwi Fortean, Guy Powell. At least, they sent in aspects of the same story, about a bull’s brain cavity housing some kind of small animal. The other Hibbert lived in London and seems to have accounted for the vast bulk of the material attributed to that name. I know nothing more about E. M. G. Hibbert; I only know a little more about W. P. Hibbert.

W. P. Hibbert was almost certainly Wallace P(atrick?) Hibbert, born July 1912 in Barnet, a borough in Middlesex, part of northern London. He married Marjorie L. Coles. After World War II, the Hibberts were involved in the perfume business. Around April 1947, they joined with Raoul Pellegrin to form Cie de Dandon en Provence, which was engaged in buying and selling perfumes and related cosmetics. The company, addressed at Aldwych House, in London, had 100 pounds as starting capital.

That business seems to have soured quickly. Five months later, in September, “The Chemist and Druggist” (a trade journal) reported that the Hibberts were partnered with W. J. Watson to form Picot, Ltd. The business description was the same; the address the same; and the capitalization was the same, too. Picot continued for a number of years. In 1963, the journal reported it celebrated its silver anniversary. The managing director presented W. P. Hibbert—founder, and still chairman—with a coat-of-arms depicting the company’s history. (I am not sure what happened to Marjorie.) Later, Picot was acquired by Scott & Browne, a chemistry-based business, and subsequently was sold and broken apart.

I believe that Hibbert died in 1971. He would have been 58 or 59.

*****************

I do not know how or when Hibbert came to Forteanism, nor do I have a really firm grasp on his interpretation of the subject. The dearth of material forces me to speculate based on pretty thin evidence. But he does seem to have been a consistent and committed Fortean.

Hibbert began corresponding with the Fortean Society in 1951, and appearing in Doubt the following year, which suggests that he made acquaintance with the Fortean Society around the beginning of the decade. For most of the Forteans I have so far studied, this timing is unusual. There was no big push around this time and, indeed, a number of Forteans dropped away in the 1950s. Even the Society’s main force in England, Eric Frank Russell, was losing his enthusiasm for the group. Still, there were plenty of references to Fort and the Society in English culture, albeit in obscure places. Perhaps Hibbert was interested in science fiction; he seems to have had some occult leanings, which could have led him to certain bookstores or magazines that featured references to Fort and the Society.

The existing correspondence about his membership—between Tiffany Thayer and Russell, between Hibbert or his business-associates and Russell—concerns almost exclusively books he bought via the Society. In April 1951 he purchased something published by Methuen. The following year he bought Albert Jay Nock’s “memoirs of a Superfluous Man” and Henry C. Roberts’s book on Nostradamus. In 1953, he wrote Russell trying to get ahold of a book Thayer was flogging, Robert Lindner’s “Prescription for Rebellion.”

It is of course dangerous to try extracting much information from a person’s book-buying habits. But the purchases do suggest that Hibbert had some interest in the occult—Nostradamus—and in left-libertarian thought—both of the other books. (I do not know what the Methuen book was.) And at least some of this is supported by the material that he sent into Doubt.

Once he started corresponding with Thayer and Russell, Hibbert seems to have been a consistent supplier of material. His name appeared 20 times between Doubt 38 (October 1952) and Doubt 57 (July 1958). A lot of what he sent in is impossible to categorize, since Thayer merely credited him for sending in some clipping, but not what. Of the material that can be identified, though, a lot of it can be understood as skeptical of government or (broadly speaking) occult. He sent in material about the debate over a pure food bill in England that included the politicians behaving childish, calling each other name. Other clippings had those in power keeping secret important information: in one case, the Liverpool police department investigated some of its own employees, declared the accusations against them groundless, but would not specify what those accusations were. Another article he sent in was about a judge who decreed 65 books should be destroyed as obscene. One of the books was “The Decameron.”

It is also worth remembering that when Tiffany Thayer was naming London Forteans who might be interested in Caresse Crosby's world citizen advocacy, he mentioned Hibbert. The correspondence between Hibbert and Thayer--lost, as far as I know--gave Thayer the impression (at least) that Hibbert was dissatisfied with national governments.

Material related to the occult—following the literal definition of unseen forces—conformed to standard categories established by Fort. In one case, the moon above London looked blue, and scientists explained this away as resulting from light diffraction by tiny uniform particles in the atmosphere. He sent in newspaper reports of frogs raining on Italy and metal falling from the sky in Spain. He also contributed to a large flood of information on the Herrmann family of Long Island, which was supposedly haunted by poltergeists. Their story received a great deal of media coverage.

A third category of clippings sent in by Hibbert also focused on occult forces, but dealt specifically with seeming chemical and biochemical mysteries—which have an edge because Hibbert’s own work was so closely related to chemistry. One wonders how he saw the science of perfume and cosmetics. Was he pragmatic? Did he have unusual theories? Did he draw some distinction between the chemistry of perfumes and other chemical analyses? I don’t know. But the clippings suggest, at the very least, Hibbert was entertained by stories of eccentric chemists.

Thus, he contributed material on Charles Burkett and Brian Williams, who were both supposedly able to power a light bulb with their hand alone. And a Portuguese man who was imprisoned for fraud after claiming he could synthesize petroleum; equipped by the Minister of Economics with a laboratory in jail, he successfully created the chemical. (Officials were keeping the process secret.) Dr. Edward Hogarth Hopkinson had his electricity cut off for not paying his bills—but the lights stayed on. The power company accused him of stealing the juice. He said he kept his house running with a nuclear fission egg, but he could not reveal the mechanics of it, because of of the Hippocratic Oath. The Boyd Medical Research Institute in Glasgow conducted tests that showed drugs diluted to such an extent that not one molecule could be detected were still extremely potent.

The other portion of the correspondence about him refers to his becoming a dealer of Doubt. Around the end of 1953 or beginning of 1954, he contacted Thayer about getting five copies of Doubt each time, for the wholesale price of one dollar per batch. These he distributed—to whom I am not sure. As of September 1958, he was still paying for these extra issues. And as of January 1959, he was still paying his annual dues.

Hibbert stayed a Fortean, it seems, until the Fortean Society’s bitter end, or just about. Thayer would die only seven months later, in August 1959, and the Society would be no more.

I believe that Hibbert died in 1971. He would have been 58 or 59.

*****************

I do not know how or when Hibbert came to Forteanism, nor do I have a really firm grasp on his interpretation of the subject. The dearth of material forces me to speculate based on pretty thin evidence. But he does seem to have been a consistent and committed Fortean.

Hibbert began corresponding with the Fortean Society in 1951, and appearing in Doubt the following year, which suggests that he made acquaintance with the Fortean Society around the beginning of the decade. For most of the Forteans I have so far studied, this timing is unusual. There was no big push around this time and, indeed, a number of Forteans dropped away in the 1950s. Even the Society’s main force in England, Eric Frank Russell, was losing his enthusiasm for the group. Still, there were plenty of references to Fort and the Society in English culture, albeit in obscure places. Perhaps Hibbert was interested in science fiction; he seems to have had some occult leanings, which could have led him to certain bookstores or magazines that featured references to Fort and the Society.

The existing correspondence about his membership—between Tiffany Thayer and Russell, between Hibbert or his business-associates and Russell—concerns almost exclusively books he bought via the Society. In April 1951 he purchased something published by Methuen. The following year he bought Albert Jay Nock’s “memoirs of a Superfluous Man” and Henry C. Roberts’s book on Nostradamus. In 1953, he wrote Russell trying to get ahold of a book Thayer was flogging, Robert Lindner’s “Prescription for Rebellion.”

It is of course dangerous to try extracting much information from a person’s book-buying habits. But the purchases do suggest that Hibbert had some interest in the occult—Nostradamus—and in left-libertarian thought—both of the other books. (I do not know what the Methuen book was.) And at least some of this is supported by the material that he sent into Doubt.

Once he started corresponding with Thayer and Russell, Hibbert seems to have been a consistent supplier of material. His name appeared 20 times between Doubt 38 (October 1952) and Doubt 57 (July 1958). A lot of what he sent in is impossible to categorize, since Thayer merely credited him for sending in some clipping, but not what. Of the material that can be identified, though, a lot of it can be understood as skeptical of government or (broadly speaking) occult. He sent in material about the debate over a pure food bill in England that included the politicians behaving childish, calling each other name. Other clippings had those in power keeping secret important information: in one case, the Liverpool police department investigated some of its own employees, declared the accusations against them groundless, but would not specify what those accusations were. Another article he sent in was about a judge who decreed 65 books should be destroyed as obscene. One of the books was “The Decameron.”

It is also worth remembering that when Tiffany Thayer was naming London Forteans who might be interested in Caresse Crosby's world citizen advocacy, he mentioned Hibbert. The correspondence between Hibbert and Thayer--lost, as far as I know--gave Thayer the impression (at least) that Hibbert was dissatisfied with national governments.

Material related to the occult—following the literal definition of unseen forces—conformed to standard categories established by Fort. In one case, the moon above London looked blue, and scientists explained this away as resulting from light diffraction by tiny uniform particles in the atmosphere. He sent in newspaper reports of frogs raining on Italy and metal falling from the sky in Spain. He also contributed to a large flood of information on the Herrmann family of Long Island, which was supposedly haunted by poltergeists. Their story received a great deal of media coverage.

A third category of clippings sent in by Hibbert also focused on occult forces, but dealt specifically with seeming chemical and biochemical mysteries—which have an edge because Hibbert’s own work was so closely related to chemistry. One wonders how he saw the science of perfume and cosmetics. Was he pragmatic? Did he have unusual theories? Did he draw some distinction between the chemistry of perfumes and other chemical analyses? I don’t know. But the clippings suggest, at the very least, Hibbert was entertained by stories of eccentric chemists.

Thus, he contributed material on Charles Burkett and Brian Williams, who were both supposedly able to power a light bulb with their hand alone. And a Portuguese man who was imprisoned for fraud after claiming he could synthesize petroleum; equipped by the Minister of Economics with a laboratory in jail, he successfully created the chemical. (Officials were keeping the process secret.) Dr. Edward Hogarth Hopkinson had his electricity cut off for not paying his bills—but the lights stayed on. The power company accused him of stealing the juice. He said he kept his house running with a nuclear fission egg, but he could not reveal the mechanics of it, because of of the Hippocratic Oath. The Boyd Medical Research Institute in Glasgow conducted tests that showed drugs diluted to such an extent that not one molecule could be detected were still extremely potent.

The other portion of the correspondence about him refers to his becoming a dealer of Doubt. Around the end of 1953 or beginning of 1954, he contacted Thayer about getting five copies of Doubt each time, for the wholesale price of one dollar per batch. These he distributed—to whom I am not sure. As of September 1958, he was still paying for these extra issues. And as of January 1959, he was still paying his annual dues.

Hibbert stayed a Fortean, it seems, until the Fortean Society’s bitter end, or just about. Thayer would die only seven months later, in August 1959, and the Society would be no more.