A Fortean in practice, if not inclination or theorizing, and no fan of the Fortean Society (although a member) nor, seemingly, Fort himself. The story of W. L. McAtee raises again the question of who counts as a Fortean, and why.

McAtee’s work also gives new insight into ideas about Forteana in the years just before Fort wrote.

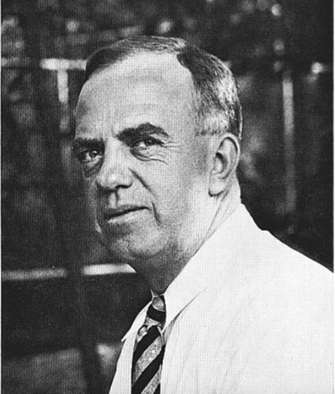

Waldo Lee McAtee was born 21 January 1883—less than a decade after Fort himself—in Jalapa, Indiana to John Henry and Anna Morris. Thomas a a carpenter, and the family moved to Marion, Indiana, while Waldo was still a child. He had five siblings, two brothers and three sisters, all younger than him, two of whom died in childhood. He was close with his maternal grandfather, who introduced him to outdoor pursuits such as hiking and fishing. As McAtee remembered later in life, the family was poor, although he didn’t remember any particular deprivations.

When he was 16, McAtee attended a lecture by the ornithologist Frank M. Chapman, who inspired him to take up the study of birds. He became close with a couple of teachers in high school and—with the help of a loan from one—studied at Indiana University. He also worked during the time, including acting as curator of birds at the University museum. Between his junior and senior years—the summer of 1903—he joined the federal government’s Bureau of Biological Survey, taking a permanent position the following year. In 1906 he completed a master’s thesis on the relationship between horned larks and agriculture; that was also the year he married Fannie E. Lawson. They had three children. The eldest, a boy named Jack, died as a baby. The couple also had a daughter and a second son.

McAtee’s work also gives new insight into ideas about Forteana in the years just before Fort wrote.

Waldo Lee McAtee was born 21 January 1883—less than a decade after Fort himself—in Jalapa, Indiana to John Henry and Anna Morris. Thomas a a carpenter, and the family moved to Marion, Indiana, while Waldo was still a child. He had five siblings, two brothers and three sisters, all younger than him, two of whom died in childhood. He was close with his maternal grandfather, who introduced him to outdoor pursuits such as hiking and fishing. As McAtee remembered later in life, the family was poor, although he didn’t remember any particular deprivations.

When he was 16, McAtee attended a lecture by the ornithologist Frank M. Chapman, who inspired him to take up the study of birds. He became close with a couple of teachers in high school and—with the help of a loan from one—studied at Indiana University. He also worked during the time, including acting as curator of birds at the University museum. Between his junior and senior years—the summer of 1903—he joined the federal government’s Bureau of Biological Survey, taking a permanent position the following year. In 1906 he completed a master’s thesis on the relationship between horned larks and agriculture; that was also the year he married Fannie E. Lawson. They had three children. The eldest, a boy named Jack, died as a baby. The couple also had a daughter and a second son.

Through the next decade-and-a-half McAtee worked his way through the BBS, which was then coming into its own as an agency. The work focused on surveying the nation’s species and studying their ecological activities, especially as they related to agriculture. He was first de facto, then de jure, leader of the Section of Economic Ornithology, overseeing a number of studies on the stomach contents of birds—a way of figuring out what they were eating and how they related to their environment. But from the beginning he also had other interests, in folklore, in poetry, and in scientific oddities. During the 1920s and 1930s, he battled with others in the federal government over the direction of national wildlife policy, which was becoming increasingly focused on killing predators. (McAtee pushed for continuing scientific research and helped to found the Wildlife Society and edit its journal The Journal of Wildlife Management.) He also staked out a position against the growing Darwinian consensus in American biology—after the so-called eclipse of Darwinism in the 1910s and 1920s. Mcatee retired from government service in 1947.

When he was almost seventy, McAtee told (Fortean) Don Bloch, “I am only a collector in the forbidden fields and have no theories to uphold or great works to build. I simply collect what appeals to me, record it, and forget about it. It may be of use to someone sometime and that is enough for me.” That’s not exactly true, and especially not representative of his earlier career, when he had scientific theories to promote—nor of his developed ideas about what constituted proper poetry—but it is accurate in characterizing himself as a collector. He collected words, for example—placing ones that interested him on index cards, with their source and a representative sentence—which he provided to dictionaries, while dictionaries still accepted contributions from amateurs, and which he used in his folkloric research. He collected insects and plants, which he used in his taxonomic work; he collected books—including pornographic works, that he donated to the University of North Carolina, to edify the Bible Belt—and bibliographic references. (He was very much the bureaucrat, and one can imagine that he had extensive files.) And he collected facts that interested him, which led to a number of various, small publications—he published more than a hundred papers, and privately put out many more than that, through his life, but his big book on Darwinism was denied by all publishers and so, like many Forteans, he made his ideas known most as a pamphleteer. Probably his best known work was Nomina Abitera, a 1945 pamphlet that included scatalogical and sexual place names across America—Killpecker Creek in Wyoming, as an instance.

Early in his career, as Fort was compiling his first book, but before he had published it, McAtee stumbled on a vein of Forteana: reports of organic matter that rained from the sky. He wrote about these in an article for the U.S. Monthly Weather Review (45, 1917, 217-224), an obscure enough arena, but it was commented on by the likes of Cold Spring Harbor’s Experiment Station Record, Science, The Literary Digest, Scientific American and Geographical Review. The study was animated by a Fortean curiosity, even if it was organized by a more bureaucratic mind. McAtee noted accounts of organic rains—from ants to rats—could be found throughout history but, lately, these had been discounted because they were usually given a supernatural explanation at the time. “However,” he said, “so many wonderful things occur in nature that negation of any observation is dangerous; it is better to preserve a judicial attitude and regard all [authentic] information that comes to hand as so much evidence, some of it supporting one side, some the other, of a given problem.” He himself was loathe to dismiss the phenomena because a friend—the entomologist Andrew Nelson Caudell—and his father had both reported seeing with their own eyes such weird rains, Caudell having found puddles of earthworms in a buggy seat (which reminded his own mother of a time minnows fell from the sky), his father finding worms on the brim of his hat when he came in from a storm. He could also cite the eminent scientist Francis Castlenau, who had seen fishes rain down in Singapore.

He went on to offer a solution, one that would become the standard explanation against which Forteans would rail: that the rains were caused by winds, sometimes whirling vortices, that could lift up animals and cast them down somewhere else. He himself had seen a hat tossed over buildings in Washington, D.C., and of course tornadoes were well known in their power to move the seemingly immobile. Enough reason, then, to believe in the general phenomenon, at least for McAtee. Although he was quick to admit—and enumerate—that there were many “spurious” cases. Among these were insect larvae, which were simply driven from their places of hibernation; and ants, which can fly on their own, and sometimes do so in great numbers; honey and sugar, which are just sap falling from trees; grains, which have merely been washed down from surrounding plants during rainstorms; black rains, which are just soot; red rains, which came from caterpillar chrysalises or algae; manna, which are just lichens that probably did not even fall from the sky.

Which left some true anomalies—which, in McAtee’s handling, weren’t that anomalous. He continued in his paper, considering each one, each under a subsection, so that his seven page article was divided into 23 parts. There were true red rains, he said—not blood—caused by dust and algae. Pollen does rain down—itself a phenomenon, but also possibly explaining the so-called sulphur (read: yellow) rains; rains of hay are easily explained by wind; a report of strange paper he explained as dried algae; a similar cause explained jelly or flesh rains. And on he went, occasionally only recording that a fall seemed genuine—as in the case of some mussels coming out of the sky. He spent a great deal of time on frog falls, the classic Fortean example, collating a number of examples, from ancient sources to more modern ones. (Indeed, whatever explanations he offered, the paper was a rich bibliographic source.) He then turned to fish and other vertebrates—in none of these cases offering an explanation. That he reserved for the next section, on wind. And here he returned to his biological interests: how important was wind as a distributor of life. He doubted that it was very important for vertebrates, including frogs, most of which he assumed either traveled a short distance or would arrive dead. But wind could be important in spreading plants and algae—which was how he concluded the piece.

McAtee’s piece prompted an editorial comment in Scientific American which was even more accepting of the possibility of such rains. The author—anonymous—was surprised, given the power of wind, that more such falls were not reported. (He—for presumably the author was a man—then gave a brief resume of McAtee’s already brief article.) That short piece in Scientific American prompted further remark in The Literary Digest, which cited the piece approvingly and included a long quotation—almost the whole of the article. All of which is to say that even as Fort was compiling his first book, there was public discussion about that most Fortean of events, strange things falling from the sky, and it was even approving. Sam Moskowitz, among others, has pointed out that Fort may have been influenced by French writers of science fiction who were also writing about perils from above—Moskowitz’s point is to somehow discredit Fort for not being more innovative. But everyone has their sources. Fort was likely influenced by French science fiction writers. And McAtee’s article would become grist for his mill—but he put it to very different uses, much less sanguine about easy solutions to the problem of weird rains than McAtee.

Fort wrote in Chapter 19 of The Book of the Damned, “My own notion is that, in the summer of 1896, something, or some beings, came as near to this earth as they could, upon a hunting expedition; that, in the summer of 1896, an expedition of super-scientists passed over this earth, and let down a dragnet -- and what would it catch, sweeping through the air, supposing it to have reached not quite to this earth?

“In the Monthly Weather Review, May, 1917, W. L. McAtee quotes from the Baton Rouge correspondence to the Philadelphia Times:

“That, in the summer of 1896, into the streets of Baton Rouge, La., and from a "clear sky," fell hundreds of dead birds. There were wild ducks, and cat birds, woodpeckers, and "many birds of strange plumage," some of them resembling canaries.

“Usually one does not have to look very far from any place to learn of a storm. But the best that could be done in this instance was to say:

"There had been a storm on the coast of Florida."

“And, unless he have psycho-chemic repulsion for the explanation, the reader feels only momentary astonishment that dead birds from a storm in Florida should fall from an unstormy sky in Louisiana, and with his intellect greased like the plumage of a wild duck, the datum then drops off.

“Our greasy, shiny brains. That they may be of some use after all: that other modes of existence place a high value upon them as lubricants; that we're hunted for them; a hunting expedition to this earth -- the newspapers report a tornado.

“If from a clear sky, or a sky in which there were no driven clouds, or other evidences of still-continuing wind-power -- or, if from a storm in Florida, it could be accepted that hundreds of birds had fallen far away, in Louisiana, I conceive, conventionally, of heavier objects having fallen in Alabama, say, and of the fall of still heavier objects still nearer the origin in Florida.

“The sources of information of the Weather Bureau are widespread. “It has no records of such falls. “So a drag net that was let down from above somewhere -- “Or something that I learned from the more scientific of the investigators of psychic phenomena:

“The reader begins their work with prejudice against telepathy and everything else of psychic phenomena. The writers deny spirit-communication, and say that the seeming data are data of "only telepathy." Astonishing instances of seeming clairvoyance -- "only telepathy." After a while the reader finds himself agreeing that it's only telepathy -- which, at first, had been intolerable to him.

“So maybe, in 1896, a super-dragnet did not sweep through this earth's atmosphere, gathering up all the birds within its field, the meshes then suddenly breaking --

“Or that the birds of Baton Rouge were only from the Super-Sargasso Sea --

“Upon which we shall have another expression. We thought we'd settled that, and we thought we'd establish that, but nothing's ever settled, and nothing's ever established, in a real sense, if, in a real sense, there is nothing but queasiness.

“I suppose there had been a storm somewhere, the storm in Florida, perhaps, and many birds had been swept upward into the Super-Sargasso Sea. It has frigid regions and it has tropical regions -- that birds of diverse species had been swept upward, into an icy region, where, huddling together for warmth, they had died. Then, later, they had been dislodged -- meteor coming along -- boat -- bicycle -- dragon -- don't know what did come along -- something dislodged them.

“So leaves of trees, carried up there is whirlwinds, staying there years, ages, perhaps only a few months, but then falling to this earth at an unseasonable time for dead leaves -- fishes carried up there, some of them dying and drying, some of them living in volumes of water that are in abundance up there, or that fall sometimes in the deluges that we call "cloudbursts."

“The astronomers won't think kindly of us, and we haven't done anything to endear ourselves to the meteorologists -- but we're weak and mawkish Intermediatists -- several times we've tried to get the aeronauts with us -- extraordinary things up there: things that curators of museums would give up all hope of ever being fixed stars, to obtain: things left over from whirlwinds of the time of the Pharaohs, perhaps: or that Elijah did go up in the sky in something like a chariot, and may not be Vega, after all, and that there may be a wheel or so left of whatever he went up in. We basely suggest that it would bring a high price -- but sell soon, because after a while there'd be thousands of them hawked around --

“We weakly drop a hint to the aeronauts.”

What followed, over the years, were two (almost) parallel discussions about creatures falling from the sky, discussions that would not intersect until the early 1930s. One discussion was Fortean and would be continued by Fort through until the end of his life, his various books continuing to mention such rains. The other was conducted by scientists. In 1921, E. W. Gudger, an ichthyologist at the American Museum of Natural History published a review on the topic—having been partially inspired by McAtee (and also by James Ellsworth De Kay). Published in the Museum’s magazine (Natural History), Gudger’s article went into even greater detail than McAtee’s had, though it was focused only on fish. (He had been reading and writing encyclopedically as editor of Bibliography of Fishes.) Among his reports were those by a number of eminent scientific men, forty-four in all (though nothing from Fort). Gudger admitted that many of these cases were hearsay, but the general phenomenon could not be discounted, and offered four possible explanations: fish that migrate overland having been left high and dry; fish left behind by receding floodwaters; estivating fish awakened by rains; and waterspouts—the last a variation on McAtee’s winds.

A year later, the possibility of raining animals appeared in another scientific book, and then again at the end of the 1920s. The 1922 mention came in a book on meteorology by Charles Fitzhugh Talman, which approvingly reviewed McAtee’s article. In 1929, Gudger revisited the topic in an article for the Annals and Magazine of Natural History, which updated his accounts. The first article had elicited a number of letters, with citations he had not seen, and his own subsequent work uncovered even more accounts of fish rains. He thought it worthwhile to update what he had done eight years before. His general thesis, though, was the same—that there were several possibilities to account for the these reports, though winds and waterspouts were the most likely. Two years later, Talman produced another book on meteorology, The Realm of the Air, which continued to admit the possibility of fish rains and explain them as the the result of winds and spouts.

That year, 1931, was, of course, also the year that Lo! appeared in bookstores. Fort’s most accessible and publicized book, Lo! continued to cite such prodigious rains as a mockery of science. The Literary Review considered Fort’s book—it wasn’t quite a review—singling out his interest in anomalous rains, and then turning to Talman as offering a perfectly scientific explanation. Encysted within the long excerpt from Talman’s book were ideas from McAtee’s article, including the part at which he muses why the reports are not more common. The Literary Review was trying to show that Fort had oversold his heretic credentials. Mostly it showed that there was a great deal of concern at the time with—in Talman’s phrase—The Realm of the Air and that the various discourses did not often overlap, though Fort was trying to combine scientific theorizing with ideas from French science fiction to paint a picture of the sky—and what lay beyond—as weird.

After the brief intersection, the two courses again mostly diverged. The Fortean discourse was confined to Doubt, where Tiffany Thayer and some of his correspondents mocked the scientific explanation offered by McAtee and Gudger and Talman, in ways similar to what Fort did in The Book of the Damned: that the explanations were rote and unspecific. Unlike the falls themselves—which often occurred well away from the supposed storms that caused the fish to be uplifted in the first place. And that the reports often emphasized that only one species of fish was found to have fallen. Thayer even mentioned McAtee’s reports once, in Doubt 25 (May 1949), but only to prove that even officialdom took the general phenomenon seriously, not to embrace the explanation.

The scientific discourse was carried forward by Grudger, but not only by him. In the late 1930s, there were debates among biogeographers about how animals moved across vast differences—this was before continental drift was generally accepted. One explanation offered was that small creatures—such as spiders and frogs—could be carried by wind. Philip Jackson Darlington, who literally wrote the book on vertebrate biogeography, championed this idea and to prove its feasibility spent one afternoon, at the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology, where he worked, with Thomas Barbour, a herpetologist who did not accept the possibility, dropping frogs from a high museum story. They were stunned when they landed—dead, Barbour, thought—but eventually moved, suggesting that the mechanism of movement was at least theoretically possible. Grudger wrote another article on the subject a few years later—this one a letter to the premiere American journal, Science, which included now not only rains of fish, but frogs, too.

By this point, a dissenting voice had arisen in the scientific discourse, though it was not from a scientist. The Northwestern University English Professor Bergen Evans was attempting to redefine the meaning of the term skeptic—in such a way that it would cut out the Forteans. (At the time, Forteans were a part of the skeptical community, allied especially in Thayer’s atheism.) Evans did not think any of Gudger’s accounts were likely. He responded in a separate letter to Science. He took up the matter in his book, released that year, a seminal document in the reworked skeptical movement, The Natural History of Nonsense, an excerpt of which—including this topic—appeared in The Atlantic Monthly. Evans argued that no scientifically-trained person had ever had fish fall on him (or her) and therefore all the many reports should be dismissed as superstition. He further suspected that the high proportion of them that came from the late nineteenth-century were the result of certain heretical paleontological theories.

Evans did not offer citations, in his article or his book, so it is unclear to which paleontological thinkers he is referring. But we can hazard a guess, and the answer, ironically, leads us back to the Fortean Society. The idea that the Noachian deluge had left fossils high in mountains had largely been disproved buy the early- to -mid-nineteenth century, such that even those who argued for Genesis above geology—to reduce the conflict to its vulgar outlines—had abandoned that line of reasoning. The exception was some Americans, notably Samuel Webb and Isaac Newton Vail. These authors argued that there had been a canopy of ice or water around the earth, like Saturn’s rings, which at one point fell to the earth, causing the flood. Historians Ronald L. Numbers says that origins of this belief are obscure, and that’s true, but they seem likely to be related to the rise of New Thought.

Isaac Newton Vail, of course, had become a Fortean cause célèbre, thanks to Thayer, and that may have made Evans think his ideas had been more prominent, or more connected to Fortean thought. It’s also true that there were some later authors working with the same idea, particularly Carl Theodore Schwarze, which again may have left the impression that the ideas were prominent. Interestingly, while the only connection between Fort and these ideas seemed to have been forged after his death, during Thayer’s running of the Fortean Society, there is certainly a parallel. A canopy of water, circling the earth high in the heavens, even if it is mostly vapor—one that left, at least, some fossil remnants—that sure sounds like a Super-Sargasso Sea plied by alien ships dropping things—rains of fish and frogs—on the earth below.

By the late 1940s, there were a number of other reported fish and fall frogs. Especially important was a rain of fish in Marksville, Louisiana, witnessed by Dr. A. D. Barkov and reported to Science. Doubt dutifully reported the occasion, along with a note that the science column penned by John J’ O’Neill, which had covered Evans’s book, provoked a number of letters by writers swearing they had seen such falls. As it stands today, Evans’s position is still represented, but the sheer number of fish fall and frog rain reports remains hard to explains.

*********

McAtee’s collecting led him to other heterodox positions that were parallel to Fortean ideas. In one article, he reviewed the possibility that birds could be luminous—like deep-sea fish—and concluded it happened occasionally, in owls that nested in old trees, and became dusted with luminous fungi, and on herons, for unknown reasons. This too was a review of the literature and had been a topic of speculation in the early part of the 1900s; I haven’t read McAtee’s article, so it may be that he had been carrying around the idea since then. The idea is nonetheless well within the Fortean purview—a natural anomaly—and there has been some writing along these lines, such as David W. Clarke, “The Luminous Owls of Norfolk” Fortean Studies 1 (1994): 50-58.

Of more lasting importance was his writing against natural selection. From the large manuscript that was never published, he did extract several papers, three of which were published in the Ohio Journal of Science, which was mainstream but small-scale. His early thinking on the matter seems to have evolved out of his wildlife research; he studied to stomach contents of hundreds of thousands of birds, in the course of his career, trying to figure out what they ate. He thought that the data gave him some insight into the question of protective coloration and mimicry—the idea that some non-poisonous insects, for example, might adapt to look like poisonous ones. In a 1932 article for Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections-also mainstream, also offtrail—he argued that this data did not support the idea of protective adaptations. He continued to argue along these lines through the early 1930s, including an article in the relatively prestigious Quarterly Review of Biology. He went out on a limb in these arguments, dismissing the possibility that frogs could even possess toxic substances in their skin. His argument based on the study of stomach contents was also limited, since he had no data about the relative abundance of insects in the environment, to know whether birds were shunning certain species or preferring other ones.

Two articles appeared in the same issue of the Ohio Journal of Science, September 1936. These argued that the analogy Darwin made between artificial and natural selection could not hold, because natural selection was not as careful and conscientious as artificial selection, concluding, “If belief in ‘natural selection’ depends on its analogy to artificial selection then that belief can scarcely prevail.” The other attack was similar to one offered by Fort, although McAtee did not cite, or even mention, Fort: it was that the definition of “fitness” was tautological, the fit being those that survived, and those that survived being fit. Or, as Fort said,

“The fittest survive.

What is meant by the fittest?

Not the strongest; not the cleverest--

Weakness and stupidity everywhere survive.

There is no way of determining fitness except in that a thing does survive.

'Fitness,' then, is only another name for 'survival.'

Darwinism:

That survivors survive.”

McAtee came back to the subject again in the late 1940s. In 1949, he published the third article on Darwinism for the Ohio State Journal of Science, this one arguing that numerical abundance was not a sign of a species’ success. Although he could point to a few people who were making arguments along these lines, and also quote some Darwin that seemed to be arguing that greater numbers was a sign of greater success, this was largely an argument against a straw man. Indeed, at the very time that McAtee was writing against natural selection, a care of biologists was putting natural selection on its firmest scientific footing—an process called the evolutionary synthesis—weaving together taxonomy, botany, population genetics, theoretical genetics, and paleontology to uncover many of the processes at work in evolution. With McAtee’s own book unpublished, he turned to pamphleteering, his usual practice late in life, privately printing and sending out “Contradictions in Darwinian Sourcebooks.” After he died, some of his arguments were adopted by the creationist movement. (Not unlike the case of another Fortean, Norman Macbeth, whose anthroposophical and legal objections to the logic of natural selection were absorbed into the creationist movement.)

********************

McAtee connects to Forteanism in a lot of ways then—his study of animal rains, his skepticism of natural selection. Raised religious, he became—at best—agnostic, claiming the only ethical ideal needed was the Golden Rule and sure that science had made Christian theology silly. (It was once possible to imagine a heaven beyond the moon, he wrote in another privately published pamphlet, but with telescopes able to see light-years away, heaven had to be moved so far, now, that it would take a soul millions and millions of years to reach it.) Like so many Forteans, he was cantankerous: “As for me, I believe that we’re on a toboggan to hell and the track is greased,” he told fellow Fortean Don Bloch.

But he was not a Fortean, not really. He was on the mold of Thayer’s hero, H. L. Mencken, another cantankerous skeptic, but one who held science in high regard, and would not board the Fortean bus. Indeed, McAtee and Mencken were in correspondence, both fascinated by demotic English and how it developed. Unlike Mencken, though, who—to Thayer’s everlasting chagrin—refused to join the Fortean Society, McAtee did join. The reason is not mysterious. It was for a friend.

In late 1945, Don Bloch, an active Fortean and former employee of the Fish and Wildlife Service, suggested to Thayer that he recruit McAtee. By this point, Bloch had left Washington, D.C., and was living in Denver, so he may not have had a chance to sound out McAtee on the idea, but probably thought that McAtee fit the Society so well that he should be a member. In December of that year, Thayer said he would approach McAtee. Eight months later, on 28 August 1946, Thayer reported to Bloch that McAtee had agreed to join as an Honorary Fellow.

Thayer seemed pleased enough. In the next issue of Doubt (16, January 1947), he listed as available from the Society Mcatee’s “Nomina abitera” as well as another pamphlet which attacked Darwinism, particularly as expressed by John Burroughs and Joseph Grinell. (McAtee had gone after Burroughs, as well as Thoreau, for arguing that birds were adapted to their environment, which he saw as a source of Darwinian error.) Later in the year, he made sure that Eric Frank Russell received a copy of Mcatee’s pamphlet on place names—it fit with their scatological (and sophomoric) sense of humor. Thayer made sure to note that McAtee was an honorary fellow.

Two years later, when McAtee put together his anti-natural selection pamphlet, Thayer obtained some and offered them to the readership of Doubt (#24, April 1949):“MFS McAtee, who has been battling Darwinian dogma almost single-handed for the past decade or longer, has ‘excerpted’ the high-lights of Contradictions in Darwinian Source-books and published them in a pamphlet bearing that title. It runs to eleven pages plus paper cover, and a very few copies are available. Each copy should be preserved in a public library, eventually, so we suggest that interested members buy copies, study them, and then take pains to place them in institutions where they will be appreciated, catalogued, and kept available for future Forteans. While they last--$1.00 each from the Society.” Apparently, the Fortean Society members were not as intrigued, since—despite the small number—Thayer was still offering them six years later, in Doubt 48 (1955).

Thayer, though, seems to have been keen on McAtee and seen him as a bulwark against the developing changes in skepticism that had been heralded by Bergen Evans—the connecting of atheism with a fervid acceptance in science as the measure of rationality. In Doubt 25 (summer 1950), he wrote, under the title “Deplorable,” “Lou Alt, a former MFS, now an atheist kingpin in Philly, permits his publication, called ‘The Liberal’ (God deliver us from a liberal’s caress!.) [sic] to defend dogmatic evolution. The ‘Liberal’s’ challenge is addressed to Jehovah’s Witnesses who publish AWAKE--which is, aside from its mystical nonsense, a well reasoned and well written paper. We suggest that the Philly Liberals, Alt & Co, challenge MFS McAtee to debate ‘evolution’ with them. McAtee is no deist and no Witness for Jehovah. In fact, he’s a practicing, teaching biologist, U of Chicago, but he doesn’t hold with Darwin, and he has his own definition of evolution.”

For all the warm welcome, though, McAtee does not seem to have been very interested in the Society. He provided his pamphlets—which he may just have seen as a way of bettering their distribution. And besides the times listed above, I see his name only once more in the pages of Doubt; he sent in an excerpt from Amelia M. Murray’s Letters from the United States, Cuba and Canada (1856), which mentioned sea serpents and argued for their existence. It is not clear what prompted McAtee to send in the clipping. Perhaps there had been correspondence, but I find no mention of it in the letters I have seen between Bloch and McAtee; Bloch and Thayer; or Thayer and Russell. The excerpt was published in Doubt 18 (July 1947), but certainly could have been sent with the original package of material that McAtee provided and withheld by Thayer until it could be used in his magazine.

There was some correspondence between Thayer and McAtee in 1951, but I have not been able to find it. All I have found is mention of it—and an (incomplete) explanation of why McAtee did not feel comfortable with the Society. There may be more buried in McAtee’s papers at the Library of Congress, which are extensive. What I do have is a letter from McAtee to Bloch, dated 24 October 1951. It reads, in part, “Thanks for commenting on and returning T. Thayer’s letter.” That’s how we know that Thayer, at least, wrote to McAtee, but what he said is unknown, as is the cause for the letter. Mcatee then went on to explain why he wasn’t interested in the Society. (Note that he underlined all his “u”s throughout his correspondence with Bloch.) “I have my fair share (perhaps more) of skepticism of beliefs and theories, but I also have respect for the hard-won approximations to knowledge that scientists steer by until some improvement is achieved. The attitude of “Doubt” seems unintelligent mockery and there is little in it that attracts my sympathy.”

Ironically, in the exact same letter, he went on to discuss how he collected words to contribute to the dictionary, listing them on index cards with dates of use and sentence examples. He was so very Fortean, in so many ways. And yet he refused the title. So what does that make him? My general opinion is that a Fortean is anyone who calls themself a Fortean, however near or far their attitudes seem from Fort’s own, and since McAtee did not call himself one and distanced himself from the Society, he does not belong to the class. Rather, his activities, his ideas, point toward the wider skeptical tradition still active in the 1940s and 1950s.

The Forteans—and McAtee—complicate the history of freethinking, even as it is being revised by the likes of Susan Jacoby. The idea is that free thought was alive throughout the end of the nineteenth century, but by the 1930s the seeds of what would become the so-called “age of unreason” were being sown. The problem with this idea is that it conflates free thought with secularism—when there were plenty of Forteans with a mystical bent chafing against the constraints of convention—and rationality with science. It’s a whig history written by the current mold of skeptics. In this historical narrative, Fort himself becomes a damned fact, as do the Forteans and, to a lesser extent, McAtee: skeptics, free thinkers, rationalists, who did not embrace science—and were often wrong—and so get lumped into what Jacoby calls a universe of “junk thought.”

As any Fortean should know, history is never as clean, clear, or easy as we’d like to think. McAtee shows us that.

When he was almost seventy, McAtee told (Fortean) Don Bloch, “I am only a collector in the forbidden fields and have no theories to uphold or great works to build. I simply collect what appeals to me, record it, and forget about it. It may be of use to someone sometime and that is enough for me.” That’s not exactly true, and especially not representative of his earlier career, when he had scientific theories to promote—nor of his developed ideas about what constituted proper poetry—but it is accurate in characterizing himself as a collector. He collected words, for example—placing ones that interested him on index cards, with their source and a representative sentence—which he provided to dictionaries, while dictionaries still accepted contributions from amateurs, and which he used in his folkloric research. He collected insects and plants, which he used in his taxonomic work; he collected books—including pornographic works, that he donated to the University of North Carolina, to edify the Bible Belt—and bibliographic references. (He was very much the bureaucrat, and one can imagine that he had extensive files.) And he collected facts that interested him, which led to a number of various, small publications—he published more than a hundred papers, and privately put out many more than that, through his life, but his big book on Darwinism was denied by all publishers and so, like many Forteans, he made his ideas known most as a pamphleteer. Probably his best known work was Nomina Abitera, a 1945 pamphlet that included scatalogical and sexual place names across America—Killpecker Creek in Wyoming, as an instance.

Early in his career, as Fort was compiling his first book, but before he had published it, McAtee stumbled on a vein of Forteana: reports of organic matter that rained from the sky. He wrote about these in an article for the U.S. Monthly Weather Review (45, 1917, 217-224), an obscure enough arena, but it was commented on by the likes of Cold Spring Harbor’s Experiment Station Record, Science, The Literary Digest, Scientific American and Geographical Review. The study was animated by a Fortean curiosity, even if it was organized by a more bureaucratic mind. McAtee noted accounts of organic rains—from ants to rats—could be found throughout history but, lately, these had been discounted because they were usually given a supernatural explanation at the time. “However,” he said, “so many wonderful things occur in nature that negation of any observation is dangerous; it is better to preserve a judicial attitude and regard all [authentic] information that comes to hand as so much evidence, some of it supporting one side, some the other, of a given problem.” He himself was loathe to dismiss the phenomena because a friend—the entomologist Andrew Nelson Caudell—and his father had both reported seeing with their own eyes such weird rains, Caudell having found puddles of earthworms in a buggy seat (which reminded his own mother of a time minnows fell from the sky), his father finding worms on the brim of his hat when he came in from a storm. He could also cite the eminent scientist Francis Castlenau, who had seen fishes rain down in Singapore.

He went on to offer a solution, one that would become the standard explanation against which Forteans would rail: that the rains were caused by winds, sometimes whirling vortices, that could lift up animals and cast them down somewhere else. He himself had seen a hat tossed over buildings in Washington, D.C., and of course tornadoes were well known in their power to move the seemingly immobile. Enough reason, then, to believe in the general phenomenon, at least for McAtee. Although he was quick to admit—and enumerate—that there were many “spurious” cases. Among these were insect larvae, which were simply driven from their places of hibernation; and ants, which can fly on their own, and sometimes do so in great numbers; honey and sugar, which are just sap falling from trees; grains, which have merely been washed down from surrounding plants during rainstorms; black rains, which are just soot; red rains, which came from caterpillar chrysalises or algae; manna, which are just lichens that probably did not even fall from the sky.

Which left some true anomalies—which, in McAtee’s handling, weren’t that anomalous. He continued in his paper, considering each one, each under a subsection, so that his seven page article was divided into 23 parts. There were true red rains, he said—not blood—caused by dust and algae. Pollen does rain down—itself a phenomenon, but also possibly explaining the so-called sulphur (read: yellow) rains; rains of hay are easily explained by wind; a report of strange paper he explained as dried algae; a similar cause explained jelly or flesh rains. And on he went, occasionally only recording that a fall seemed genuine—as in the case of some mussels coming out of the sky. He spent a great deal of time on frog falls, the classic Fortean example, collating a number of examples, from ancient sources to more modern ones. (Indeed, whatever explanations he offered, the paper was a rich bibliographic source.) He then turned to fish and other vertebrates—in none of these cases offering an explanation. That he reserved for the next section, on wind. And here he returned to his biological interests: how important was wind as a distributor of life. He doubted that it was very important for vertebrates, including frogs, most of which he assumed either traveled a short distance or would arrive dead. But wind could be important in spreading plants and algae—which was how he concluded the piece.

McAtee’s piece prompted an editorial comment in Scientific American which was even more accepting of the possibility of such rains. The author—anonymous—was surprised, given the power of wind, that more such falls were not reported. (He—for presumably the author was a man—then gave a brief resume of McAtee’s already brief article.) That short piece in Scientific American prompted further remark in The Literary Digest, which cited the piece approvingly and included a long quotation—almost the whole of the article. All of which is to say that even as Fort was compiling his first book, there was public discussion about that most Fortean of events, strange things falling from the sky, and it was even approving. Sam Moskowitz, among others, has pointed out that Fort may have been influenced by French writers of science fiction who were also writing about perils from above—Moskowitz’s point is to somehow discredit Fort for not being more innovative. But everyone has their sources. Fort was likely influenced by French science fiction writers. And McAtee’s article would become grist for his mill—but he put it to very different uses, much less sanguine about easy solutions to the problem of weird rains than McAtee.

Fort wrote in Chapter 19 of The Book of the Damned, “My own notion is that, in the summer of 1896, something, or some beings, came as near to this earth as they could, upon a hunting expedition; that, in the summer of 1896, an expedition of super-scientists passed over this earth, and let down a dragnet -- and what would it catch, sweeping through the air, supposing it to have reached not quite to this earth?

“In the Monthly Weather Review, May, 1917, W. L. McAtee quotes from the Baton Rouge correspondence to the Philadelphia Times:

“That, in the summer of 1896, into the streets of Baton Rouge, La., and from a "clear sky," fell hundreds of dead birds. There were wild ducks, and cat birds, woodpeckers, and "many birds of strange plumage," some of them resembling canaries.

“Usually one does not have to look very far from any place to learn of a storm. But the best that could be done in this instance was to say:

"There had been a storm on the coast of Florida."

“And, unless he have psycho-chemic repulsion for the explanation, the reader feels only momentary astonishment that dead birds from a storm in Florida should fall from an unstormy sky in Louisiana, and with his intellect greased like the plumage of a wild duck, the datum then drops off.

“Our greasy, shiny brains. That they may be of some use after all: that other modes of existence place a high value upon them as lubricants; that we're hunted for them; a hunting expedition to this earth -- the newspapers report a tornado.

“If from a clear sky, or a sky in which there were no driven clouds, or other evidences of still-continuing wind-power -- or, if from a storm in Florida, it could be accepted that hundreds of birds had fallen far away, in Louisiana, I conceive, conventionally, of heavier objects having fallen in Alabama, say, and of the fall of still heavier objects still nearer the origin in Florida.

“The sources of information of the Weather Bureau are widespread. “It has no records of such falls. “So a drag net that was let down from above somewhere -- “Or something that I learned from the more scientific of the investigators of psychic phenomena:

“The reader begins their work with prejudice against telepathy and everything else of psychic phenomena. The writers deny spirit-communication, and say that the seeming data are data of "only telepathy." Astonishing instances of seeming clairvoyance -- "only telepathy." After a while the reader finds himself agreeing that it's only telepathy -- which, at first, had been intolerable to him.

“So maybe, in 1896, a super-dragnet did not sweep through this earth's atmosphere, gathering up all the birds within its field, the meshes then suddenly breaking --

“Or that the birds of Baton Rouge were only from the Super-Sargasso Sea --

“Upon which we shall have another expression. We thought we'd settled that, and we thought we'd establish that, but nothing's ever settled, and nothing's ever established, in a real sense, if, in a real sense, there is nothing but queasiness.

“I suppose there had been a storm somewhere, the storm in Florida, perhaps, and many birds had been swept upward into the Super-Sargasso Sea. It has frigid regions and it has tropical regions -- that birds of diverse species had been swept upward, into an icy region, where, huddling together for warmth, they had died. Then, later, they had been dislodged -- meteor coming along -- boat -- bicycle -- dragon -- don't know what did come along -- something dislodged them.

“So leaves of trees, carried up there is whirlwinds, staying there years, ages, perhaps only a few months, but then falling to this earth at an unseasonable time for dead leaves -- fishes carried up there, some of them dying and drying, some of them living in volumes of water that are in abundance up there, or that fall sometimes in the deluges that we call "cloudbursts."

“The astronomers won't think kindly of us, and we haven't done anything to endear ourselves to the meteorologists -- but we're weak and mawkish Intermediatists -- several times we've tried to get the aeronauts with us -- extraordinary things up there: things that curators of museums would give up all hope of ever being fixed stars, to obtain: things left over from whirlwinds of the time of the Pharaohs, perhaps: or that Elijah did go up in the sky in something like a chariot, and may not be Vega, after all, and that there may be a wheel or so left of whatever he went up in. We basely suggest that it would bring a high price -- but sell soon, because after a while there'd be thousands of them hawked around --

“We weakly drop a hint to the aeronauts.”

What followed, over the years, were two (almost) parallel discussions about creatures falling from the sky, discussions that would not intersect until the early 1930s. One discussion was Fortean and would be continued by Fort through until the end of his life, his various books continuing to mention such rains. The other was conducted by scientists. In 1921, E. W. Gudger, an ichthyologist at the American Museum of Natural History published a review on the topic—having been partially inspired by McAtee (and also by James Ellsworth De Kay). Published in the Museum’s magazine (Natural History), Gudger’s article went into even greater detail than McAtee’s had, though it was focused only on fish. (He had been reading and writing encyclopedically as editor of Bibliography of Fishes.) Among his reports were those by a number of eminent scientific men, forty-four in all (though nothing from Fort). Gudger admitted that many of these cases were hearsay, but the general phenomenon could not be discounted, and offered four possible explanations: fish that migrate overland having been left high and dry; fish left behind by receding floodwaters; estivating fish awakened by rains; and waterspouts—the last a variation on McAtee’s winds.

A year later, the possibility of raining animals appeared in another scientific book, and then again at the end of the 1920s. The 1922 mention came in a book on meteorology by Charles Fitzhugh Talman, which approvingly reviewed McAtee’s article. In 1929, Gudger revisited the topic in an article for the Annals and Magazine of Natural History, which updated his accounts. The first article had elicited a number of letters, with citations he had not seen, and his own subsequent work uncovered even more accounts of fish rains. He thought it worthwhile to update what he had done eight years before. His general thesis, though, was the same—that there were several possibilities to account for the these reports, though winds and waterspouts were the most likely. Two years later, Talman produced another book on meteorology, The Realm of the Air, which continued to admit the possibility of fish rains and explain them as the the result of winds and spouts.

That year, 1931, was, of course, also the year that Lo! appeared in bookstores. Fort’s most accessible and publicized book, Lo! continued to cite such prodigious rains as a mockery of science. The Literary Review considered Fort’s book—it wasn’t quite a review—singling out his interest in anomalous rains, and then turning to Talman as offering a perfectly scientific explanation. Encysted within the long excerpt from Talman’s book were ideas from McAtee’s article, including the part at which he muses why the reports are not more common. The Literary Review was trying to show that Fort had oversold his heretic credentials. Mostly it showed that there was a great deal of concern at the time with—in Talman’s phrase—The Realm of the Air and that the various discourses did not often overlap, though Fort was trying to combine scientific theorizing with ideas from French science fiction to paint a picture of the sky—and what lay beyond—as weird.

After the brief intersection, the two courses again mostly diverged. The Fortean discourse was confined to Doubt, where Tiffany Thayer and some of his correspondents mocked the scientific explanation offered by McAtee and Gudger and Talman, in ways similar to what Fort did in The Book of the Damned: that the explanations were rote and unspecific. Unlike the falls themselves—which often occurred well away from the supposed storms that caused the fish to be uplifted in the first place. And that the reports often emphasized that only one species of fish was found to have fallen. Thayer even mentioned McAtee’s reports once, in Doubt 25 (May 1949), but only to prove that even officialdom took the general phenomenon seriously, not to embrace the explanation.

The scientific discourse was carried forward by Grudger, but not only by him. In the late 1930s, there were debates among biogeographers about how animals moved across vast differences—this was before continental drift was generally accepted. One explanation offered was that small creatures—such as spiders and frogs—could be carried by wind. Philip Jackson Darlington, who literally wrote the book on vertebrate biogeography, championed this idea and to prove its feasibility spent one afternoon, at the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology, where he worked, with Thomas Barbour, a herpetologist who did not accept the possibility, dropping frogs from a high museum story. They were stunned when they landed—dead, Barbour, thought—but eventually moved, suggesting that the mechanism of movement was at least theoretically possible. Grudger wrote another article on the subject a few years later—this one a letter to the premiere American journal, Science, which included now not only rains of fish, but frogs, too.

By this point, a dissenting voice had arisen in the scientific discourse, though it was not from a scientist. The Northwestern University English Professor Bergen Evans was attempting to redefine the meaning of the term skeptic—in such a way that it would cut out the Forteans. (At the time, Forteans were a part of the skeptical community, allied especially in Thayer’s atheism.) Evans did not think any of Gudger’s accounts were likely. He responded in a separate letter to Science. He took up the matter in his book, released that year, a seminal document in the reworked skeptical movement, The Natural History of Nonsense, an excerpt of which—including this topic—appeared in The Atlantic Monthly. Evans argued that no scientifically-trained person had ever had fish fall on him (or her) and therefore all the many reports should be dismissed as superstition. He further suspected that the high proportion of them that came from the late nineteenth-century were the result of certain heretical paleontological theories.

Evans did not offer citations, in his article or his book, so it is unclear to which paleontological thinkers he is referring. But we can hazard a guess, and the answer, ironically, leads us back to the Fortean Society. The idea that the Noachian deluge had left fossils high in mountains had largely been disproved buy the early- to -mid-nineteenth century, such that even those who argued for Genesis above geology—to reduce the conflict to its vulgar outlines—had abandoned that line of reasoning. The exception was some Americans, notably Samuel Webb and Isaac Newton Vail. These authors argued that there had been a canopy of ice or water around the earth, like Saturn’s rings, which at one point fell to the earth, causing the flood. Historians Ronald L. Numbers says that origins of this belief are obscure, and that’s true, but they seem likely to be related to the rise of New Thought.

Isaac Newton Vail, of course, had become a Fortean cause célèbre, thanks to Thayer, and that may have made Evans think his ideas had been more prominent, or more connected to Fortean thought. It’s also true that there were some later authors working with the same idea, particularly Carl Theodore Schwarze, which again may have left the impression that the ideas were prominent. Interestingly, while the only connection between Fort and these ideas seemed to have been forged after his death, during Thayer’s running of the Fortean Society, there is certainly a parallel. A canopy of water, circling the earth high in the heavens, even if it is mostly vapor—one that left, at least, some fossil remnants—that sure sounds like a Super-Sargasso Sea plied by alien ships dropping things—rains of fish and frogs—on the earth below.

By the late 1940s, there were a number of other reported fish and fall frogs. Especially important was a rain of fish in Marksville, Louisiana, witnessed by Dr. A. D. Barkov and reported to Science. Doubt dutifully reported the occasion, along with a note that the science column penned by John J’ O’Neill, which had covered Evans’s book, provoked a number of letters by writers swearing they had seen such falls. As it stands today, Evans’s position is still represented, but the sheer number of fish fall and frog rain reports remains hard to explains.

*********

McAtee’s collecting led him to other heterodox positions that were parallel to Fortean ideas. In one article, he reviewed the possibility that birds could be luminous—like deep-sea fish—and concluded it happened occasionally, in owls that nested in old trees, and became dusted with luminous fungi, and on herons, for unknown reasons. This too was a review of the literature and had been a topic of speculation in the early part of the 1900s; I haven’t read McAtee’s article, so it may be that he had been carrying around the idea since then. The idea is nonetheless well within the Fortean purview—a natural anomaly—and there has been some writing along these lines, such as David W. Clarke, “The Luminous Owls of Norfolk” Fortean Studies 1 (1994): 50-58.

Of more lasting importance was his writing against natural selection. From the large manuscript that was never published, he did extract several papers, three of which were published in the Ohio Journal of Science, which was mainstream but small-scale. His early thinking on the matter seems to have evolved out of his wildlife research; he studied to stomach contents of hundreds of thousands of birds, in the course of his career, trying to figure out what they ate. He thought that the data gave him some insight into the question of protective coloration and mimicry—the idea that some non-poisonous insects, for example, might adapt to look like poisonous ones. In a 1932 article for Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections-also mainstream, also offtrail—he argued that this data did not support the idea of protective adaptations. He continued to argue along these lines through the early 1930s, including an article in the relatively prestigious Quarterly Review of Biology. He went out on a limb in these arguments, dismissing the possibility that frogs could even possess toxic substances in their skin. His argument based on the study of stomach contents was also limited, since he had no data about the relative abundance of insects in the environment, to know whether birds were shunning certain species or preferring other ones.

Two articles appeared in the same issue of the Ohio Journal of Science, September 1936. These argued that the analogy Darwin made between artificial and natural selection could not hold, because natural selection was not as careful and conscientious as artificial selection, concluding, “If belief in ‘natural selection’ depends on its analogy to artificial selection then that belief can scarcely prevail.” The other attack was similar to one offered by Fort, although McAtee did not cite, or even mention, Fort: it was that the definition of “fitness” was tautological, the fit being those that survived, and those that survived being fit. Or, as Fort said,

“The fittest survive.

What is meant by the fittest?

Not the strongest; not the cleverest--

Weakness and stupidity everywhere survive.

There is no way of determining fitness except in that a thing does survive.

'Fitness,' then, is only another name for 'survival.'

Darwinism:

That survivors survive.”

McAtee came back to the subject again in the late 1940s. In 1949, he published the third article on Darwinism for the Ohio State Journal of Science, this one arguing that numerical abundance was not a sign of a species’ success. Although he could point to a few people who were making arguments along these lines, and also quote some Darwin that seemed to be arguing that greater numbers was a sign of greater success, this was largely an argument against a straw man. Indeed, at the very time that McAtee was writing against natural selection, a care of biologists was putting natural selection on its firmest scientific footing—an process called the evolutionary synthesis—weaving together taxonomy, botany, population genetics, theoretical genetics, and paleontology to uncover many of the processes at work in evolution. With McAtee’s own book unpublished, he turned to pamphleteering, his usual practice late in life, privately printing and sending out “Contradictions in Darwinian Sourcebooks.” After he died, some of his arguments were adopted by the creationist movement. (Not unlike the case of another Fortean, Norman Macbeth, whose anthroposophical and legal objections to the logic of natural selection were absorbed into the creationist movement.)

********************

McAtee connects to Forteanism in a lot of ways then—his study of animal rains, his skepticism of natural selection. Raised religious, he became—at best—agnostic, claiming the only ethical ideal needed was the Golden Rule and sure that science had made Christian theology silly. (It was once possible to imagine a heaven beyond the moon, he wrote in another privately published pamphlet, but with telescopes able to see light-years away, heaven had to be moved so far, now, that it would take a soul millions and millions of years to reach it.) Like so many Forteans, he was cantankerous: “As for me, I believe that we’re on a toboggan to hell and the track is greased,” he told fellow Fortean Don Bloch.

But he was not a Fortean, not really. He was on the mold of Thayer’s hero, H. L. Mencken, another cantankerous skeptic, but one who held science in high regard, and would not board the Fortean bus. Indeed, McAtee and Mencken were in correspondence, both fascinated by demotic English and how it developed. Unlike Mencken, though, who—to Thayer’s everlasting chagrin—refused to join the Fortean Society, McAtee did join. The reason is not mysterious. It was for a friend.

In late 1945, Don Bloch, an active Fortean and former employee of the Fish and Wildlife Service, suggested to Thayer that he recruit McAtee. By this point, Bloch had left Washington, D.C., and was living in Denver, so he may not have had a chance to sound out McAtee on the idea, but probably thought that McAtee fit the Society so well that he should be a member. In December of that year, Thayer said he would approach McAtee. Eight months later, on 28 August 1946, Thayer reported to Bloch that McAtee had agreed to join as an Honorary Fellow.

Thayer seemed pleased enough. In the next issue of Doubt (16, January 1947), he listed as available from the Society Mcatee’s “Nomina abitera” as well as another pamphlet which attacked Darwinism, particularly as expressed by John Burroughs and Joseph Grinell. (McAtee had gone after Burroughs, as well as Thoreau, for arguing that birds were adapted to their environment, which he saw as a source of Darwinian error.) Later in the year, he made sure that Eric Frank Russell received a copy of Mcatee’s pamphlet on place names—it fit with their scatological (and sophomoric) sense of humor. Thayer made sure to note that McAtee was an honorary fellow.

Two years later, when McAtee put together his anti-natural selection pamphlet, Thayer obtained some and offered them to the readership of Doubt (#24, April 1949):“MFS McAtee, who has been battling Darwinian dogma almost single-handed for the past decade or longer, has ‘excerpted’ the high-lights of Contradictions in Darwinian Source-books and published them in a pamphlet bearing that title. It runs to eleven pages plus paper cover, and a very few copies are available. Each copy should be preserved in a public library, eventually, so we suggest that interested members buy copies, study them, and then take pains to place them in institutions where they will be appreciated, catalogued, and kept available for future Forteans. While they last--$1.00 each from the Society.” Apparently, the Fortean Society members were not as intrigued, since—despite the small number—Thayer was still offering them six years later, in Doubt 48 (1955).

Thayer, though, seems to have been keen on McAtee and seen him as a bulwark against the developing changes in skepticism that had been heralded by Bergen Evans—the connecting of atheism with a fervid acceptance in science as the measure of rationality. In Doubt 25 (summer 1950), he wrote, under the title “Deplorable,” “Lou Alt, a former MFS, now an atheist kingpin in Philly, permits his publication, called ‘The Liberal’ (God deliver us from a liberal’s caress!.) [sic] to defend dogmatic evolution. The ‘Liberal’s’ challenge is addressed to Jehovah’s Witnesses who publish AWAKE--which is, aside from its mystical nonsense, a well reasoned and well written paper. We suggest that the Philly Liberals, Alt & Co, challenge MFS McAtee to debate ‘evolution’ with them. McAtee is no deist and no Witness for Jehovah. In fact, he’s a practicing, teaching biologist, U of Chicago, but he doesn’t hold with Darwin, and he has his own definition of evolution.”

For all the warm welcome, though, McAtee does not seem to have been very interested in the Society. He provided his pamphlets—which he may just have seen as a way of bettering their distribution. And besides the times listed above, I see his name only once more in the pages of Doubt; he sent in an excerpt from Amelia M. Murray’s Letters from the United States, Cuba and Canada (1856), which mentioned sea serpents and argued for their existence. It is not clear what prompted McAtee to send in the clipping. Perhaps there had been correspondence, but I find no mention of it in the letters I have seen between Bloch and McAtee; Bloch and Thayer; or Thayer and Russell. The excerpt was published in Doubt 18 (July 1947), but certainly could have been sent with the original package of material that McAtee provided and withheld by Thayer until it could be used in his magazine.

There was some correspondence between Thayer and McAtee in 1951, but I have not been able to find it. All I have found is mention of it—and an (incomplete) explanation of why McAtee did not feel comfortable with the Society. There may be more buried in McAtee’s papers at the Library of Congress, which are extensive. What I do have is a letter from McAtee to Bloch, dated 24 October 1951. It reads, in part, “Thanks for commenting on and returning T. Thayer’s letter.” That’s how we know that Thayer, at least, wrote to McAtee, but what he said is unknown, as is the cause for the letter. Mcatee then went on to explain why he wasn’t interested in the Society. (Note that he underlined all his “u”s throughout his correspondence with Bloch.) “I have my fair share (perhaps more) of skepticism of beliefs and theories, but I also have respect for the hard-won approximations to knowledge that scientists steer by until some improvement is achieved. The attitude of “Doubt” seems unintelligent mockery and there is little in it that attracts my sympathy.”

Ironically, in the exact same letter, he went on to discuss how he collected words to contribute to the dictionary, listing them on index cards with dates of use and sentence examples. He was so very Fortean, in so many ways. And yet he refused the title. So what does that make him? My general opinion is that a Fortean is anyone who calls themself a Fortean, however near or far their attitudes seem from Fort’s own, and since McAtee did not call himself one and distanced himself from the Society, he does not belong to the class. Rather, his activities, his ideas, point toward the wider skeptical tradition still active in the 1940s and 1950s.

The Forteans—and McAtee—complicate the history of freethinking, even as it is being revised by the likes of Susan Jacoby. The idea is that free thought was alive throughout the end of the nineteenth century, but by the 1930s the seeds of what would become the so-called “age of unreason” were being sown. The problem with this idea is that it conflates free thought with secularism—when there were plenty of Forteans with a mystical bent chafing against the constraints of convention—and rationality with science. It’s a whig history written by the current mold of skeptics. In this historical narrative, Fort himself becomes a damned fact, as do the Forteans and, to a lesser extent, McAtee: skeptics, free thinkers, rationalists, who did not embrace science—and were often wrong—and so get lumped into what Jacoby calls a universe of “junk thought.”

As any Fortean should know, history is never as clean, clear, or easy as we’d like to think. McAtee shows us that.