Two icons of alternative science and minor German Forteans.

Ernst Fuhrmann was born 19 November 1886 in Hamburg Germany. Apparently he was born to a well-off family, which allowed him ample free time to follow his passions.

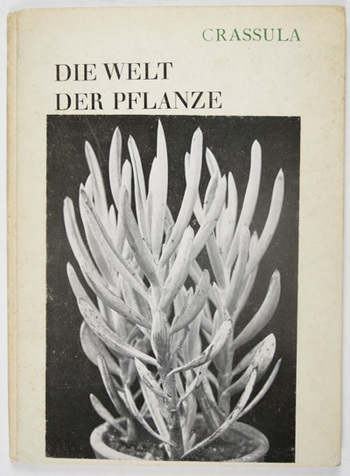

He is most famous for having founded a holistic form of biological sciences called ‘Biosophy’—this was in the years prior to World War I, when holism was important to German sciences. He was also a renowned photographer, publisher, and poet. His ideas had a mystical bent. He emphasized the need to reuse waste—compost—in agriculture, as a reflection of an eternal cycle, and also that animals and plants express the same vital substance in different ways; his photographs of plants was meant to bring out their animalistic aspects.

Fuhrmann had some association with the Nazis; but, according to Oliver A. I. Botar, he was “ambivalent at best.” By the mid-1930s, he was apparently being persecuted by the fascist regime, and in 1938 emigrated to New York, leaving behind an extensive estate.

Ernst Fuhrmann was born 19 November 1886 in Hamburg Germany. Apparently he was born to a well-off family, which allowed him ample free time to follow his passions.

He is most famous for having founded a holistic form of biological sciences called ‘Biosophy’—this was in the years prior to World War I, when holism was important to German sciences. He was also a renowned photographer, publisher, and poet. His ideas had a mystical bent. He emphasized the need to reuse waste—compost—in agriculture, as a reflection of an eternal cycle, and also that animals and plants express the same vital substance in different ways; his photographs of plants was meant to bring out their animalistic aspects.

Fuhrmann had some association with the Nazis; but, according to Oliver A. I. Botar, he was “ambivalent at best.” By the mid-1930s, he was apparently being persecuted by the fascist regime, and in 1938 emigrated to New York, leaving behind an extensive estate.

He died in New York City one day short of his birthday, 18 November 1956. He was 69.

Fuhrmann came to Forteanism in the late 1940s—this was when Thayer was making a real go of the Society and its magazine, after an uneven relaunch in the late 1930s and troubles with friends during the war years. Apparently, he heard of Fuhrmann through the German Fortean Heinz Kloss—and, it seems, the two actually met, Fuhrmann impressing Thayer a great deal. The connection was made in early 1948; Thayer told Eric Frank Russell, in March 1948, “Have you ever heard of Ernst Fuhrmann? He is here—and appears to have the boldest imagination I have encountered since Fort.” Russell apparently asked about Fuhrmann, and Thayer reiterated his appreciation in June: “Brightest guy I’ve talked to since Fort died.”

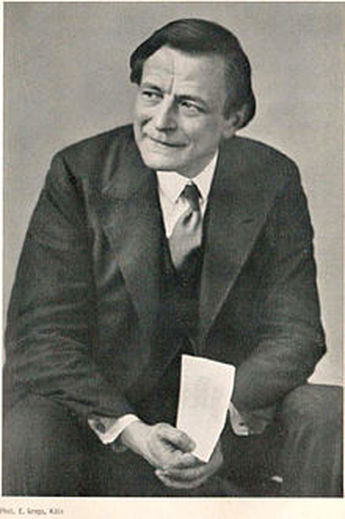

Thayer told Russell that Fuhrmann would be mentioned in Doubt 21, out that same month, and indeed he was, under the title “Living Genius.” He waxed eloquent—Thayer was always looking for intellectual heroes: “Most of the men the Society has ‘discovered’ as neglected or spat-upon for their ideas had already joined Charles Fort in Hades or were tottering on the brink before we came upon their work. Now we have found an authentic genius, entirely unsung in this country but somewhat better known in Germany, who lives, and works at his heterodoxy every day. Neither is he an old man, but his health does want improving. This is Ernst Fuhrmann, Accepted Fellow Fortean Society.”

After calling attention to Fuhrmann’s photo and how he was brought to the Society’s attention by Kloss, Thayer continued, placing him squarely int he Fortean tradition: As long ago as 1926 AD, Fuhrmann was publishing a magazine in Germany, by title, Zwiefel, which is DOUBT. In its third year the title was changed to Auriga. We are searching for a complete file and will report. The subject matter was critical, especially of written history, philology and biology.

He had already published many books and edited several scholarly series. The range of his interests is obvious from two volumes at hand, Das Tier in der Religion [The Animal in Religion] (1922) and Der Sinn in Gegenstand [The Meaning of the Object].

“In 1931 (the year 1 FS), a collection of Fuhrmann’s work was published in ten volumes, containing papers on a world of subjects from Maori culture to Insulin. We hope to print some of these in translation, but more important than that is to present the author’s two pet theories which now run to 60 unpublished volumes, in decidedly cumbersome English.

“Philologist Fuhrmann essays to establish that all languages were once one. This makes him both critical and appreciative of MFS Sherwin’s Viking and Red Man, which attempts to prove that the Algonquin Indians spoke Norse. Fuhrmann says—so did everybody else, only it wasn’t Norse, but a much older tongue.

“Biologist Fuhrmann sets out to trace all life back to the hydra—and does so, to his own satisfaction and to the consternation of the orthodox.

The man and his work present a serious Fortean problem and a challenge which we must meet. Members who are specifically interested and who think they might help substantially, address YS in confidence.”

But for all the fulsome praise, Fuhrmann only appeared once more in the pages of Thayer’s magazine, though the two men lived in the same city into the mid-1950s. That was three issues later, number 24, dated April 1949, or thereabouts. Apparently Thayer had requested him to provide some information on himself and his ideas, which he then printed, though it is nearly impossible to extract anything from the letter:

“Even the shortest auto-biography would mean enumerating the steps of success, as I understand. Well I was not made to succeed, but to doubt. Constantly to learn while I doubted that even anything was true that I was told to learn. Thus have I looked into everything that was accessible (and before unsuccessful people all things are closed) but I went into business and looked into mines, I have been busy with plant-research as well as linguistics, ethnology and many more things.

“Certainly I am not a negativist but quite the contrary. And while there is still enough left to doubt there were numberless amazing facts I discovered. (The last was deciphering the Disc of Phaistos.)

“My work is rather a journal of the learning. Thus it is terribly extensive. What ignorance of ages has piled up makes a gigantic jungle in which every path must be tried for the first time. My ideas only are suggestions to follow one and the other trail. Since decades I had prepared a great library of my own to be well equipped. The war-machines preferred to destroy such equipment (probably because mankind feels that it would not be good to know the truth. But maybe a later age may start again from honesty. If I should doll up my biography with ‘success’ it would be altogether dishonest because i would suggest, advise [sic], while I learn but never would dictate in the wonderful courageous way of scientists: This is so. Of course when other people’s structures tumble down the next expert starts shaking them a little.

“In a monastery of the future I think people would be extremely glad to have my work and follow my trails, still learning, doubting yet accomplishing the Cathedral which one single mind is bound to outline while it is at work.

“I do not remember having slaved for others and society resents that. Why should I blame them. [sic] what should they pay for. [sic] Yet it is some misery also to continue learning, never to be so arrogant as to believe to know and thus boldly start to teach, this age more than any other would poison a seducer of the people who follow the rut.

“The last aboriginate people of this globe have interested me most. I think I resemble them, and only them. And while I doubt and and try to learn I never forget where I got lost. I always return and by and by the trails I went so many times have become reliable for others to follow. But—you see: who ever asked a native to give his autobiography? Certainly my little island now since so many years is a tiny room. But the world you find in it I think is greater than any continent thus far discovered.”

Perhaps in this missive is a partial explanation for why Fuhrmann dropped from the Society’s attention. His writing was coy and difficult in English, and German was a barrier for most members. He was also, by account, an elitist, and his arrogance may have made it hard for him and Thayer to connect. It’s also true that Thayer liked to kill his idols. The ones that maintained his adoration—Fort, Omar Khayyam and his translator, Fitzgerald—had to advantage of having died, and so could not disappoint him. There were exceptions, of course—Ezra Pound, notably—but in most cases Thayer turned on those he once approved, and it is entirely possible that he did so with Fuhrmann, too, finding little reason to try to overcome the language barrier. And so the bulk of Furhmann’s writing and ideas—imaginative as they were, stimulating as they were, Fortean as they may have been—remained unincorporated into American Forteanism. If Kloss indeed hoped to create a pan-Germanic folk consciousness, his plan faltered here.

***********

Ernst Barthel was born 17 October 1890 in Schiltigheim, a contemporary of Fuhrmann, whose thought seem to run along a parallel track. (And both these also in parallel with Rudolf Steiner, founder of Anthroposophy, a more-explicitly Christian version of Theosophy.) He was a philosopher, mathematician, and inventor, a private teacher associated with the University of Cologne, editor of the magazine Antäus, a journal for “new Reality Thinking,” and a prolific author. Barthel was similarly rooted in mysticism—in his case Christian Neo-Platonism, that emphasized the importance of geometry. (One thinks here of the American Buckminster Fuller who also had a mystical understanding of geometry.) Like Fuhrmann, Barthel ran into difficulties with the Nazis, losing his position at Cologne.

Barthel developed a construction of the earth as a plane—apparently this developed out of his workings in non-Euclidean geometry—and this idea, as much as anything else, may have drawn Thayer to Barthel as well as the cadre of Germans who were connected to the Society via Kloss. Thayer had his own heterodox view of the earth, which he only very occasionally mentioned in Doubt. He imagined the planet growing, but through stages, a cube, then a sphere, then a tube again, which could account for earthquakes, changing ideas about the shape of the world, and the fitting together of continents. Obviously, the ideas were very different, and could not be made consistent, but the idea may have been appealing to Thayer.

Barthel died 16 February 1953, aged 62.

Barthel became associated with the Fortean Society through the same route as Fuhrmann, but was not as closely connected. The first mention of Barthel in the pages of Doubt—and the only mention to come while he was still alive—was in Doubt 23 (December 1948). Thayer listed Barthel as among those whose writing Kloss had provided to the Society. If Thayer really did seek out translators of the material—and there is some evidence of that—either nothing of Barthel’s was translated, or it was never published in the magazine. It suggests, again, that language was a barrier to communication between American Forteans and Germans of a similar cast of mind.

Five years went on before Barthel graced the pages of Doubt once more, and this was to note his passing and the Society’s inability to bring him into the Fortean fold—Doubt 41 (July 1953). Thayer mentioned the death, the language barrier, continuing plans to publish his work, and that Barthel’s wife had accepted an honorary life membership in the Society, as a tribute to her husband. The next issue—Doubt 42 (October 1953) did offer for sale a pamphlet by Barthel on Goethe’s color theory—a favorite subject of German’s in the mold of Steiner. I do not know what the pamphlet was—perhaps “Komplementaristische Wellenmechanik. Eine Rechtfertigung der Goethe'schen Farbenlehre” [“Complementary Wave Mechanics. A Justification of Goethe's Theory of Color”]. Nor do I know whether it was in English or German, though I strongly suspect it was in German.

Another four years went by, and then Barthel was mentioned again, this time when the Society was making actual strides in spreading Forteanism in Germany, thanks to the work of Julian F. Parr, an English science fiction fan and diplomat, who was not hindered by the language barrier. But by this point, Barthel was merely a reference, his ideas having never been absorbed by the Society or Forteans more generally, not even his ideas about the geometry of the earth, which should have been of special interest to Thayer. In Doubt 55 (November 1957), under title “Fort in Germany,” Thayer remarked on Parr’s experiences in Germany and writing of an article about Fort and the Society for a German magazine. That magazine was a science fiction one, “Andromeda,” which served as the official publication of “a dozen German organizations of science fiction and UFO fans.”

In the course of a letter Parr wrote, which Thayer was appending, Parr had mentioned The Gesselschaft fur Erdweltschung, which he glossed as a group “fairly active in Germany” that advocated humans lived on the inside of a globe. Thayer wondered if it was “founded on the work of Karl Neupert or Ernst Barthel, which we have so often mentioned in DOUBT.” I have no idea if the Gesellschaft was so founded—though there was an obvious affinity—but more striking is his memory that Barthel had been mentioned often in Doubt. Quite the opposite. Thayer obviously linked Barthel to unusual ideas about the geometry of the planet, but otherwise he rarely showed up in Doubt. He was an adornment, a citation, but not an active force.

Fuhrmann came to Forteanism in the late 1940s—this was when Thayer was making a real go of the Society and its magazine, after an uneven relaunch in the late 1930s and troubles with friends during the war years. Apparently, he heard of Fuhrmann through the German Fortean Heinz Kloss—and, it seems, the two actually met, Fuhrmann impressing Thayer a great deal. The connection was made in early 1948; Thayer told Eric Frank Russell, in March 1948, “Have you ever heard of Ernst Fuhrmann? He is here—and appears to have the boldest imagination I have encountered since Fort.” Russell apparently asked about Fuhrmann, and Thayer reiterated his appreciation in June: “Brightest guy I’ve talked to since Fort died.”

Thayer told Russell that Fuhrmann would be mentioned in Doubt 21, out that same month, and indeed he was, under the title “Living Genius.” He waxed eloquent—Thayer was always looking for intellectual heroes: “Most of the men the Society has ‘discovered’ as neglected or spat-upon for their ideas had already joined Charles Fort in Hades or were tottering on the brink before we came upon their work. Now we have found an authentic genius, entirely unsung in this country but somewhat better known in Germany, who lives, and works at his heterodoxy every day. Neither is he an old man, but his health does want improving. This is Ernst Fuhrmann, Accepted Fellow Fortean Society.”

After calling attention to Fuhrmann’s photo and how he was brought to the Society’s attention by Kloss, Thayer continued, placing him squarely int he Fortean tradition: As long ago as 1926 AD, Fuhrmann was publishing a magazine in Germany, by title, Zwiefel, which is DOUBT. In its third year the title was changed to Auriga. We are searching for a complete file and will report. The subject matter was critical, especially of written history, philology and biology.

He had already published many books and edited several scholarly series. The range of his interests is obvious from two volumes at hand, Das Tier in der Religion [The Animal in Religion] (1922) and Der Sinn in Gegenstand [The Meaning of the Object].

“In 1931 (the year 1 FS), a collection of Fuhrmann’s work was published in ten volumes, containing papers on a world of subjects from Maori culture to Insulin. We hope to print some of these in translation, but more important than that is to present the author’s two pet theories which now run to 60 unpublished volumes, in decidedly cumbersome English.

“Philologist Fuhrmann essays to establish that all languages were once one. This makes him both critical and appreciative of MFS Sherwin’s Viking and Red Man, which attempts to prove that the Algonquin Indians spoke Norse. Fuhrmann says—so did everybody else, only it wasn’t Norse, but a much older tongue.

“Biologist Fuhrmann sets out to trace all life back to the hydra—and does so, to his own satisfaction and to the consternation of the orthodox.

The man and his work present a serious Fortean problem and a challenge which we must meet. Members who are specifically interested and who think they might help substantially, address YS in confidence.”

But for all the fulsome praise, Fuhrmann only appeared once more in the pages of Thayer’s magazine, though the two men lived in the same city into the mid-1950s. That was three issues later, number 24, dated April 1949, or thereabouts. Apparently Thayer had requested him to provide some information on himself and his ideas, which he then printed, though it is nearly impossible to extract anything from the letter:

“Even the shortest auto-biography would mean enumerating the steps of success, as I understand. Well I was not made to succeed, but to doubt. Constantly to learn while I doubted that even anything was true that I was told to learn. Thus have I looked into everything that was accessible (and before unsuccessful people all things are closed) but I went into business and looked into mines, I have been busy with plant-research as well as linguistics, ethnology and many more things.

“Certainly I am not a negativist but quite the contrary. And while there is still enough left to doubt there were numberless amazing facts I discovered. (The last was deciphering the Disc of Phaistos.)

“My work is rather a journal of the learning. Thus it is terribly extensive. What ignorance of ages has piled up makes a gigantic jungle in which every path must be tried for the first time. My ideas only are suggestions to follow one and the other trail. Since decades I had prepared a great library of my own to be well equipped. The war-machines preferred to destroy such equipment (probably because mankind feels that it would not be good to know the truth. But maybe a later age may start again from honesty. If I should doll up my biography with ‘success’ it would be altogether dishonest because i would suggest, advise [sic], while I learn but never would dictate in the wonderful courageous way of scientists: This is so. Of course when other people’s structures tumble down the next expert starts shaking them a little.

“In a monastery of the future I think people would be extremely glad to have my work and follow my trails, still learning, doubting yet accomplishing the Cathedral which one single mind is bound to outline while it is at work.

“I do not remember having slaved for others and society resents that. Why should I blame them. [sic] what should they pay for. [sic] Yet it is some misery also to continue learning, never to be so arrogant as to believe to know and thus boldly start to teach, this age more than any other would poison a seducer of the people who follow the rut.

“The last aboriginate people of this globe have interested me most. I think I resemble them, and only them. And while I doubt and and try to learn I never forget where I got lost. I always return and by and by the trails I went so many times have become reliable for others to follow. But—you see: who ever asked a native to give his autobiography? Certainly my little island now since so many years is a tiny room. But the world you find in it I think is greater than any continent thus far discovered.”

Perhaps in this missive is a partial explanation for why Fuhrmann dropped from the Society’s attention. His writing was coy and difficult in English, and German was a barrier for most members. He was also, by account, an elitist, and his arrogance may have made it hard for him and Thayer to connect. It’s also true that Thayer liked to kill his idols. The ones that maintained his adoration—Fort, Omar Khayyam and his translator, Fitzgerald—had to advantage of having died, and so could not disappoint him. There were exceptions, of course—Ezra Pound, notably—but in most cases Thayer turned on those he once approved, and it is entirely possible that he did so with Fuhrmann, too, finding little reason to try to overcome the language barrier. And so the bulk of Furhmann’s writing and ideas—imaginative as they were, stimulating as they were, Fortean as they may have been—remained unincorporated into American Forteanism. If Kloss indeed hoped to create a pan-Germanic folk consciousness, his plan faltered here.

***********

Ernst Barthel was born 17 October 1890 in Schiltigheim, a contemporary of Fuhrmann, whose thought seem to run along a parallel track. (And both these also in parallel with Rudolf Steiner, founder of Anthroposophy, a more-explicitly Christian version of Theosophy.) He was a philosopher, mathematician, and inventor, a private teacher associated with the University of Cologne, editor of the magazine Antäus, a journal for “new Reality Thinking,” and a prolific author. Barthel was similarly rooted in mysticism—in his case Christian Neo-Platonism, that emphasized the importance of geometry. (One thinks here of the American Buckminster Fuller who also had a mystical understanding of geometry.) Like Fuhrmann, Barthel ran into difficulties with the Nazis, losing his position at Cologne.

Barthel developed a construction of the earth as a plane—apparently this developed out of his workings in non-Euclidean geometry—and this idea, as much as anything else, may have drawn Thayer to Barthel as well as the cadre of Germans who were connected to the Society via Kloss. Thayer had his own heterodox view of the earth, which he only very occasionally mentioned in Doubt. He imagined the planet growing, but through stages, a cube, then a sphere, then a tube again, which could account for earthquakes, changing ideas about the shape of the world, and the fitting together of continents. Obviously, the ideas were very different, and could not be made consistent, but the idea may have been appealing to Thayer.

Barthel died 16 February 1953, aged 62.

Barthel became associated with the Fortean Society through the same route as Fuhrmann, but was not as closely connected. The first mention of Barthel in the pages of Doubt—and the only mention to come while he was still alive—was in Doubt 23 (December 1948). Thayer listed Barthel as among those whose writing Kloss had provided to the Society. If Thayer really did seek out translators of the material—and there is some evidence of that—either nothing of Barthel’s was translated, or it was never published in the magazine. It suggests, again, that language was a barrier to communication between American Forteans and Germans of a similar cast of mind.

Five years went on before Barthel graced the pages of Doubt once more, and this was to note his passing and the Society’s inability to bring him into the Fortean fold—Doubt 41 (July 1953). Thayer mentioned the death, the language barrier, continuing plans to publish his work, and that Barthel’s wife had accepted an honorary life membership in the Society, as a tribute to her husband. The next issue—Doubt 42 (October 1953) did offer for sale a pamphlet by Barthel on Goethe’s color theory—a favorite subject of German’s in the mold of Steiner. I do not know what the pamphlet was—perhaps “Komplementaristische Wellenmechanik. Eine Rechtfertigung der Goethe'schen Farbenlehre” [“Complementary Wave Mechanics. A Justification of Goethe's Theory of Color”]. Nor do I know whether it was in English or German, though I strongly suspect it was in German.

Another four years went by, and then Barthel was mentioned again, this time when the Society was making actual strides in spreading Forteanism in Germany, thanks to the work of Julian F. Parr, an English science fiction fan and diplomat, who was not hindered by the language barrier. But by this point, Barthel was merely a reference, his ideas having never been absorbed by the Society or Forteans more generally, not even his ideas about the geometry of the earth, which should have been of special interest to Thayer. In Doubt 55 (November 1957), under title “Fort in Germany,” Thayer remarked on Parr’s experiences in Germany and writing of an article about Fort and the Society for a German magazine. That magazine was a science fiction one, “Andromeda,” which served as the official publication of “a dozen German organizations of science fiction and UFO fans.”

In the course of a letter Parr wrote, which Thayer was appending, Parr had mentioned The Gesselschaft fur Erdweltschung, which he glossed as a group “fairly active in Germany” that advocated humans lived on the inside of a globe. Thayer wondered if it was “founded on the work of Karl Neupert or Ernst Barthel, which we have so often mentioned in DOUBT.” I have no idea if the Gesellschaft was so founded—though there was an obvious affinity—but more striking is his memory that Barthel had been mentioned often in Doubt. Quite the opposite. Thayer obviously linked Barthel to unusual ideas about the geometry of the planet, but otherwise he rarely showed up in Doubt. He was an adornment, a citation, but not an active force.