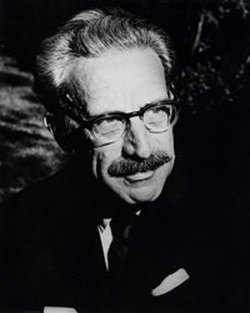

Myra Kingsley, 1946. From Life magazine.

Myra Kingsley, 1946. From Life magazine. Myra Kinglsey

Myra Kinglsey was among the cadre of astrologers attracted to—or recruited by—the Fortean Society, the parade led by Carl Payne Tobey. The relationship between astrology and Forteanism, at first blush, seems strained at beast: Fort’s own cosmological hypotheses left little room for the influence of stars (though his sense that humans might be property fit, to some extent, with the idea that human will was controlled by objects in space). Nonetheless, there were a number of professional astrologers associated with the Society, and many with an amateur interest. Likely, it seems that the Fortean Society enjoyed poking fun at astronomers was enough to attract astrologers—even if they often thought astrology itself was a kid of science, just one ignored by the mainstream. (Kinglsey was not among those astrologers who continued what she did a kind of science.)

Kingsley was born 1 October 1897 in Westport, Connecticut, to William Morgan Kinglsey and Susan (Buek) Kinglsey. She had an older brother, and both a younger brother and sister. William was in finance, the census alternately listing him as a stock broker (1900) and bank vice-president (1910). She had an early interest in music, and was taking singing lessons at age 18; her mother decided to send her to the renowned astrologer Evangeline Adams to see what might become of her career. Adams predicted that Kinglsey would forgo music for astrology, which she did.

The family seems to have broken up sometime after 1915, when they were all in the New York census together, or at least separated. The 1920 census had Susan—now going by the name Mary—heading the family in Los Angeles. Maybe they were there because of Myra’s interest in music; it’s not clear. But the whole family was there, besides William, living in a home owned free and clear with a cook and laundress. That decade seems to have been an active one for Myra. She married and divorced. She started her career in astrology. And, as of 14 April 1930, when the census was taken, she was at the Lexington Hospital, in Manhattan, having moved back East at some point. A few years later, she was visiting Bermuda.

By the late 1930s, Life magazine proclaimed her the most famous of all female astrologers. (Adams had passed by this point.) She was associated with the fecund astrology community in New York, and in 1937 did a radio show; astrology, at the time, was popular enough to support 14 different syndicated newspaper columns. But she ran afoul of government regulations, and the program ended. In the fall of 1938 she moved out to Hollywood and became an astrologer to the stars. As Life magazine had it, Kingsley was especially welcomed in southern California, where fortunes came and went and control was desperately sought but rarely won. (There was a nascent metaphysical community there, too.) The story of her coming to astrology along with the way that she practiced her art, places Kinglsey in the more conservative, more traditional camp of astrologers. Around the turn of the century, and just after, there was a movement among astrologers to rejigger their work such that it aimed at understanding the proclivities of a person, what kinds of things were fortuitous for them, and what dangerous. This practice was in contrast to those astrologers who thought themselves capable of predicting the future. Kingsley was among those who tied astrology to fortune-telling, inspired, she said, in part by Adams, who correctly predicted her own career path.

The following summer, according to Life, she predicted there would be no war in Europe; that fascism would find a foothold within the U.S. and on the continent; and that there would be a revolution in 1942. Within a few weeks, Europe had fallen into World War II. For one reason or another, she didn’t stay in southern California very long. The 1940 census has her living in Oakland with her mother, where she was still practicing astrology. (She was married, but her husband was not living with them.) Eventually, she did make her way back south. From what I have seen, her predictions tended to be very generic, even by the standards of astrology, foretelling that there would be continued conflict here and there around the globe, for example, and that the stock market would have dips and rises. (Apparently, she said these things without irony or self-consciousness.) She divorced twice before 1949, but predicted love would still come her way. (I don’t know if she ever remarried.) In 1951, she published her only book, Outrageous Fortune: How I Practice Astrology. Kirkus reviewed it thusly:

“The principles—and practice—of astrology, as Myra Kingsley, who has been highly successful, brings her talent for seeing it in the stars right down to earth and the charting of your life. The accuracy of astrological revelation as applied to happy marriages- and unhappy; babies and the predetermination of their sex; careers; money; theatre runs; death (this cannot be predicted) and disaster; war (1952 is ""bleak astrologically""); and the planetary planning of your life in general (clothes, decor, etc.). Lots of famous names brighten what is for many a dark- and doubtful-science, add to the aura of it all.”

Kingsley lived a long life, dying 20 November 1996, aged 99, in Miami.

Myra Kingsley’s connection to the Fortean Society is minor in the extreme, getting one mention in Doubt. I do not know that she ever wrote about Charles Fort or Forteanism, and her membership ma very well have been pro forma.

The mention came in Doubt 20 (March 1948), with Thayer praising the Saturday Evening Post for plugging Fort. He noted that the magazine had printed a story by Robert Spencer Carr, and included in his author’s bio a bit on Fort. Then he mentioned, “The Post went farther in that issue, taking up MFS Myra Kingsley, an astrologer.” this referred to John Kobler’s profile of Kingsley—titled “Queen of the Crystal Ball”—that ran on page 30 of the 6 December 1947 issue.

It seems likely that Kingsley had only a passing interest in Fort.

Myra Kinglsey was among the cadre of astrologers attracted to—or recruited by—the Fortean Society, the parade led by Carl Payne Tobey. The relationship between astrology and Forteanism, at first blush, seems strained at beast: Fort’s own cosmological hypotheses left little room for the influence of stars (though his sense that humans might be property fit, to some extent, with the idea that human will was controlled by objects in space). Nonetheless, there were a number of professional astrologers associated with the Society, and many with an amateur interest. Likely, it seems that the Fortean Society enjoyed poking fun at astronomers was enough to attract astrologers—even if they often thought astrology itself was a kid of science, just one ignored by the mainstream. (Kinglsey was not among those astrologers who continued what she did a kind of science.)

Kingsley was born 1 October 1897 in Westport, Connecticut, to William Morgan Kinglsey and Susan (Buek) Kinglsey. She had an older brother, and both a younger brother and sister. William was in finance, the census alternately listing him as a stock broker (1900) and bank vice-president (1910). She had an early interest in music, and was taking singing lessons at age 18; her mother decided to send her to the renowned astrologer Evangeline Adams to see what might become of her career. Adams predicted that Kinglsey would forgo music for astrology, which she did.

The family seems to have broken up sometime after 1915, when they were all in the New York census together, or at least separated. The 1920 census had Susan—now going by the name Mary—heading the family in Los Angeles. Maybe they were there because of Myra’s interest in music; it’s not clear. But the whole family was there, besides William, living in a home owned free and clear with a cook and laundress. That decade seems to have been an active one for Myra. She married and divorced. She started her career in astrology. And, as of 14 April 1930, when the census was taken, she was at the Lexington Hospital, in Manhattan, having moved back East at some point. A few years later, she was visiting Bermuda.

By the late 1930s, Life magazine proclaimed her the most famous of all female astrologers. (Adams had passed by this point.) She was associated with the fecund astrology community in New York, and in 1937 did a radio show; astrology, at the time, was popular enough to support 14 different syndicated newspaper columns. But she ran afoul of government regulations, and the program ended. In the fall of 1938 she moved out to Hollywood and became an astrologer to the stars. As Life magazine had it, Kingsley was especially welcomed in southern California, where fortunes came and went and control was desperately sought but rarely won. (There was a nascent metaphysical community there, too.) The story of her coming to astrology along with the way that she practiced her art, places Kinglsey in the more conservative, more traditional camp of astrologers. Around the turn of the century, and just after, there was a movement among astrologers to rejigger their work such that it aimed at understanding the proclivities of a person, what kinds of things were fortuitous for them, and what dangerous. This practice was in contrast to those astrologers who thought themselves capable of predicting the future. Kingsley was among those who tied astrology to fortune-telling, inspired, she said, in part by Adams, who correctly predicted her own career path.

The following summer, according to Life, she predicted there would be no war in Europe; that fascism would find a foothold within the U.S. and on the continent; and that there would be a revolution in 1942. Within a few weeks, Europe had fallen into World War II. For one reason or another, she didn’t stay in southern California very long. The 1940 census has her living in Oakland with her mother, where she was still practicing astrology. (She was married, but her husband was not living with them.) Eventually, she did make her way back south. From what I have seen, her predictions tended to be very generic, even by the standards of astrology, foretelling that there would be continued conflict here and there around the globe, for example, and that the stock market would have dips and rises. (Apparently, she said these things without irony or self-consciousness.) She divorced twice before 1949, but predicted love would still come her way. (I don’t know if she ever remarried.) In 1951, she published her only book, Outrageous Fortune: How I Practice Astrology. Kirkus reviewed it thusly:

“The principles—and practice—of astrology, as Myra Kingsley, who has been highly successful, brings her talent for seeing it in the stars right down to earth and the charting of your life. The accuracy of astrological revelation as applied to happy marriages- and unhappy; babies and the predetermination of their sex; careers; money; theatre runs; death (this cannot be predicted) and disaster; war (1952 is ""bleak astrologically""); and the planetary planning of your life in general (clothes, decor, etc.). Lots of famous names brighten what is for many a dark- and doubtful-science, add to the aura of it all.”

Kingsley lived a long life, dying 20 November 1996, aged 99, in Miami.

Myra Kingsley’s connection to the Fortean Society is minor in the extreme, getting one mention in Doubt. I do not know that she ever wrote about Charles Fort or Forteanism, and her membership ma very well have been pro forma.

The mention came in Doubt 20 (March 1948), with Thayer praising the Saturday Evening Post for plugging Fort. He noted that the magazine had printed a story by Robert Spencer Carr, and included in his author’s bio a bit on Fort. Then he mentioned, “The Post went farther in that issue, taking up MFS Myra Kingsley, an astrologer.” this referred to John Kobler’s profile of Kingsley—titled “Queen of the Crystal Ball”—that ran on page 30 of the 6 December 1947 issue.

It seems likely that Kingsley had only a passing interest in Fort.

Michael Blankfort.

Michael Blankfort. Michael Blankfort

Michael Blankfort was one of those Forteans in name only.

Born 10 December 1907 in New York City—making him the same generation as Thayer. He graduated from the University of Pennsylvania, and spent some years as a professor at Bowdoin and Princeton. Later, he became a psychologist with the New Jersey state prisons. In 1933, he started working on Broadway, which led him to Hollywood in 1937. (He inverted Thayer’s migrations; Thayer left New York for California in 1932, and returned in 1937.) He wrote short stories, novels, and the screenplay for a number of movies. The New York Times characterized one of his main themes:

“Among his 12 novels were ''A Time to Live'' in 1943, ''The Strong Hand'' in 1956, and ''An Exceptional Man'' in 1980. Many of the novels dealt with the clash of traditional Jewish values with the current cultural and social milieu. His 1965 novel ''Behold the Fire,'' based on the exploits of a small band of Jews who worked as British spies among the virulently anti-Zionist Turks in Palestine during World War I, earned him, among other honors, the S.Y. Agnon Award, given by the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.”

He joined the war effort, serving as a captain in the marines from 1952 to 1945, where he worked on training films. Afterwards, he returned to Hollywood, and the making of movies and books. During the McCarthy era, he fronted for a blacklisted writer. Married twice, he had two daughters. He died 16 July 1982 after falling on his driveway in Los Angeles and hitting his head. He was 74.

Blankfort, like Kingsley, rated only a single mention in Doubt—indeed, in the same issue, only a few lines later. Thayer was rhapsodizing about the Society’s advances: notes in the Saturday Evening Post and the Ajax Carlson, the celebrated scientist, joining (and actually paying dues). He went on to note that there were other members named Carlson—he said there were three, but named only two, the other being “the late Evans Fordyce Carlson, one-time General in the U.S. Marines.” Thayer appreciated E. F. Carlson’s political bravery:

“Despite the Fortean objections to World Fraud II, and to all such armed frauds, it was probably inevitable that we should have a ‘war’ hero. Since it was practically unavoidable, we are glad it was Carlson. He had resigned his commission to write what he wished (and knew) about Red China. He pulled as much as much democracy as possible into his contingent of Marines, enough to turn every brass hat in Washington against him ... Have your bookseller get you Twin Stars of China, by Carlson, Dodd, Mead, 1940 . . .”

The other book he recommended was a biography of Carlson called “the Big Yankee.” It was written by Blankfort and published in 1947. Oddly, the Society sold neither of these books. I am not sure why.

Blankfort’s connection to Fort, Forteanism, and the Society seems to have been entirely through the publication of that biography. A least, I have found no other. It seems likely that Thayer approached him, as a fellow writer, after the book came out, and Blankfort agreed to membership; I do not know if he actually paid dues or not. He certainly never contributed.

E. L. Brancato

I have to speculate and reach a bit to get details on this Fortean; I may be wrong.

The only biographical material on him in Doubt—he made three appearances—was that his name was E. L. Brancato, and had been in the army during World War II, stationed for a time in San Francisco. It’s not much to go on.

The jump I make is noting that there was a correspondent of the psychic Edgar Caye who went by the name E. L. Brancato, the E. in this case—based on the return address on the letter to Cayce coinciding with an address in the New York City directory—standing for Erasmus, though Brancati seems to have sometimes gone by the nickname Ed or Eddie. As it happens, Erasmus served in the army air force during World War II, though I cannot prove that he was in San Francisco. The likelihood that someone with the odd name E. L. Brancato, who served in the army, and was a correspondent of Edgar Cayce would also be a member of the Fortean Society seems high, and so I am going with the connection.

Erasmus Brancato was born 9 December 1916 in New Haven, Connecticut, making him among the younger Forteans. He graduated from Yale University, apparently its Sheffield School of Science. I cannot find him in the 1920 or 1930 census. In 1940, he was living at home, the third of seven children, and working as a secretary. (He seems to have had an interest in music, and copyrighted a piece called “Kathy” in 1940.) When he enlisted, in 1941, he was working as a baggage porter. Brancato was a short man, only 5’2” and 127 pounds. He was back in New York City by 1947. On 20 December, he married a woman named Jean (aka Jeane and Jeanne), born 1926 in Nebraska. She had graduated from Omaha Technical High School and spent a year at New Haven State Teachers College, which is apparently when she moved East. She was a housewife, doing some typing on the side.

It was in the late 1940s that Brancato became involved with Cayce. He seems to have been involved with the testing of “atomidine,” an iodine preparation that Caye recommended, though at least some of the results Brancato learned about were disappointing. In 1948, he evaluated the talents of one curative medium, concluding that she did not work through any extraordinary means, but by playing on the suggestible of the patients and alleviating psychological conditions.

I am not sure of what Brancato was doing in the 1950s. In the early 1960, his wife was involved with the “Woman’s Strike for Peace,” which got her hauled before the House Committee on Un-American Activities. She took the Fifth on most questions, including her involvement with communism. Later, in the 197os, Erasmus seems to have written and trademarked a number of puzzle books that he tried to spin off into a business.

Erasmus Lucian Brancato died 4 June 2004. He was 87.

That Brancato was listed in Doubt three times oversells his connection to the Society. The evidence is hard to judge entirely, but it seems that he likely joined the Society when he was in the army, which accords with Thayer’s address for him—though he also seems to have corresponded after he returned to New York, as well. Perhaps Thayer lost that latter contact. If Brancato did join then, it seems likely he was turned on to the Society by someone else in the military, or perhaps by the relatively recent publication of the omnibus edition of Fort’s work. San Francisco would have been a good place to learn about Fort.

At any rate, what seems to have motivated him mostly was not Fort, but that other dissident thinker George F. Gillette. In Dount 11 (Winter 1944)—indeed, the issue when the magazine became Doubt—Thayer gushed over a new discovery, “The Rational Non-Mystical Universe,” by Gillette.

“This is the first book we have discovered since the restoration of Charles Fort all in one volume, that the Society has wished to reissue. Because THIS is the theory posterity must attack if human mentality is to progress beyond it. Not Einstein. Not Newton. Not Planck. The greatest challenger of the Fortean principle of temporary acceptance--was Gillette. For his ‘cosmic’ theory, ‘a Unitary conception of all Natural Phenomena,’ embraces, envelops and includes Orthodoxy, plus Babbit, Ouspensky, Crehore, Drayson, Graydon, Blavatsky and Page. We are unaware of any cosmogony, from Pythagorous to Voliva, which Gilette’s theory cannot assimilate. In fine, we see no reason why any of them could object to being gobbled up by anything so capacious. There is room for all--and only a few simple readjustments of focus are necessary to bring all the welter of private opinions into general accord--with Gillette.

“The remunerative researches which keep so many gainfully employed need NOT be abandoned. On the contrary, all may be continued, and a raft of new ones added. Here is the book to put a stop to World Fraud III, by using up all the steel they can make and all the mental energy the race can generate. Artists are wanted to embellish the endless charts and graphs--to glorify new loves and animosities: musicians to compose new scores for the ‘spheres.’ Here is an epoch--tailor-made--waiting to be exploited. One could write about the possibilities from now on--but, please do not misunderstand.

“Our enthusiasm for Gillette’s theory is not based upon absolute approval, but upon the challenging circumstance, unique in our experience, that we can find no flaws in it--except some minor ones regarding the terms of the author’s expression, which, doubtless, he could rectify if he were still alive.

“Nobody is going to republish this adversary for us. We must do it ourselves. We are exploring the possibilities, costs, etc., etc., with a view toward doing that as soon as the alleged paper shortage will permit. We shall have to call upon subscribers to underwrite the first complete edition.”

In the late 1940s, when Thayer contemplated a Fortean University, he thought that Gillette’s writing should form the basis of an entire department. Thayer thought it was the equivalent of cosmology, with a “unitary conception of all natural phenomena . . . a single law of nature.” Brancato was taken enough with Gillette’s ideas to send $20 to support a chair in the study of his work, which Thayer reported in Doubt 20 (March 1948). But that seems to be the last time that Brancato interacted with the Society.

Five issues later, Thayer had him listed among the “lost sheep” and was pleading with the membership to reconnect him. The only address he had for him, though, was the army in San Francisco, which made hunting him down difficult.

The last mention came a couple of years later, in Doubt 29 (July 1950)—but this was probably also the first mention. Thayer was hoping to republish Gillette’s work, which had become rare, with the Society running out of its stock. (One member had just sent some material to the Society, which made reprinting seem possible.) He was contemplating a subscription to support the work—but never came through. In the meantime, he reprinted a long and confusing letter from “MFS Brancato,” which he admitted had been sent to him in the past—likely, it seems, when Brancato gave his contribution. Brancato admitted he had not read Gillette’s entire corpus but felt the need to critique several of his points. The upshot was that Gillette’ unitary view was too limiting: that there were a whole host of phenomena that existed outside of his framework and that, indeed, Forteans were in a better position to see these anomalies that one who believed what Gillette wrote.

It was a strike for Fort, and one against Thayer’s own orthodoxy. But there was never a follow up. Brancato crossed the Fortean stream and just kept going, on to his own activities, and what he saw in Fort and Forteanism remains a mystery. That he was also connected with Cayce, though, and the search for new scientific laws puts him in the mainstream of Forteanism as it was interpreted in the late 1940s—even by mild critics like John W. Campbell. But, like a Fortean phenomena, Brancato is himself mysterious, slipping away at the crucial moment.

Michael Blankfort was one of those Forteans in name only.

Born 10 December 1907 in New York City—making him the same generation as Thayer. He graduated from the University of Pennsylvania, and spent some years as a professor at Bowdoin and Princeton. Later, he became a psychologist with the New Jersey state prisons. In 1933, he started working on Broadway, which led him to Hollywood in 1937. (He inverted Thayer’s migrations; Thayer left New York for California in 1932, and returned in 1937.) He wrote short stories, novels, and the screenplay for a number of movies. The New York Times characterized one of his main themes:

“Among his 12 novels were ''A Time to Live'' in 1943, ''The Strong Hand'' in 1956, and ''An Exceptional Man'' in 1980. Many of the novels dealt with the clash of traditional Jewish values with the current cultural and social milieu. His 1965 novel ''Behold the Fire,'' based on the exploits of a small band of Jews who worked as British spies among the virulently anti-Zionist Turks in Palestine during World War I, earned him, among other honors, the S.Y. Agnon Award, given by the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.”

He joined the war effort, serving as a captain in the marines from 1952 to 1945, where he worked on training films. Afterwards, he returned to Hollywood, and the making of movies and books. During the McCarthy era, he fronted for a blacklisted writer. Married twice, he had two daughters. He died 16 July 1982 after falling on his driveway in Los Angeles and hitting his head. He was 74.

Blankfort, like Kingsley, rated only a single mention in Doubt—indeed, in the same issue, only a few lines later. Thayer was rhapsodizing about the Society’s advances: notes in the Saturday Evening Post and the Ajax Carlson, the celebrated scientist, joining (and actually paying dues). He went on to note that there were other members named Carlson—he said there were three, but named only two, the other being “the late Evans Fordyce Carlson, one-time General in the U.S. Marines.” Thayer appreciated E. F. Carlson’s political bravery:

“Despite the Fortean objections to World Fraud II, and to all such armed frauds, it was probably inevitable that we should have a ‘war’ hero. Since it was practically unavoidable, we are glad it was Carlson. He had resigned his commission to write what he wished (and knew) about Red China. He pulled as much as much democracy as possible into his contingent of Marines, enough to turn every brass hat in Washington against him ... Have your bookseller get you Twin Stars of China, by Carlson, Dodd, Mead, 1940 . . .”

The other book he recommended was a biography of Carlson called “the Big Yankee.” It was written by Blankfort and published in 1947. Oddly, the Society sold neither of these books. I am not sure why.

Blankfort’s connection to Fort, Forteanism, and the Society seems to have been entirely through the publication of that biography. A least, I have found no other. It seems likely that Thayer approached him, as a fellow writer, after the book came out, and Blankfort agreed to membership; I do not know if he actually paid dues or not. He certainly never contributed.

E. L. Brancato

I have to speculate and reach a bit to get details on this Fortean; I may be wrong.

The only biographical material on him in Doubt—he made three appearances—was that his name was E. L. Brancato, and had been in the army during World War II, stationed for a time in San Francisco. It’s not much to go on.

The jump I make is noting that there was a correspondent of the psychic Edgar Caye who went by the name E. L. Brancato, the E. in this case—based on the return address on the letter to Cayce coinciding with an address in the New York City directory—standing for Erasmus, though Brancati seems to have sometimes gone by the nickname Ed or Eddie. As it happens, Erasmus served in the army air force during World War II, though I cannot prove that he was in San Francisco. The likelihood that someone with the odd name E. L. Brancato, who served in the army, and was a correspondent of Edgar Cayce would also be a member of the Fortean Society seems high, and so I am going with the connection.

Erasmus Brancato was born 9 December 1916 in New Haven, Connecticut, making him among the younger Forteans. He graduated from Yale University, apparently its Sheffield School of Science. I cannot find him in the 1920 or 1930 census. In 1940, he was living at home, the third of seven children, and working as a secretary. (He seems to have had an interest in music, and copyrighted a piece called “Kathy” in 1940.) When he enlisted, in 1941, he was working as a baggage porter. Brancato was a short man, only 5’2” and 127 pounds. He was back in New York City by 1947. On 20 December, he married a woman named Jean (aka Jeane and Jeanne), born 1926 in Nebraska. She had graduated from Omaha Technical High School and spent a year at New Haven State Teachers College, which is apparently when she moved East. She was a housewife, doing some typing on the side.

It was in the late 1940s that Brancato became involved with Cayce. He seems to have been involved with the testing of “atomidine,” an iodine preparation that Caye recommended, though at least some of the results Brancato learned about were disappointing. In 1948, he evaluated the talents of one curative medium, concluding that she did not work through any extraordinary means, but by playing on the suggestible of the patients and alleviating psychological conditions.

I am not sure of what Brancato was doing in the 1950s. In the early 1960, his wife was involved with the “Woman’s Strike for Peace,” which got her hauled before the House Committee on Un-American Activities. She took the Fifth on most questions, including her involvement with communism. Later, in the 197os, Erasmus seems to have written and trademarked a number of puzzle books that he tried to spin off into a business.

Erasmus Lucian Brancato died 4 June 2004. He was 87.

That Brancato was listed in Doubt three times oversells his connection to the Society. The evidence is hard to judge entirely, but it seems that he likely joined the Society when he was in the army, which accords with Thayer’s address for him—though he also seems to have corresponded after he returned to New York, as well. Perhaps Thayer lost that latter contact. If Brancato did join then, it seems likely he was turned on to the Society by someone else in the military, or perhaps by the relatively recent publication of the omnibus edition of Fort’s work. San Francisco would have been a good place to learn about Fort.

At any rate, what seems to have motivated him mostly was not Fort, but that other dissident thinker George F. Gillette. In Dount 11 (Winter 1944)—indeed, the issue when the magazine became Doubt—Thayer gushed over a new discovery, “The Rational Non-Mystical Universe,” by Gillette.

“This is the first book we have discovered since the restoration of Charles Fort all in one volume, that the Society has wished to reissue. Because THIS is the theory posterity must attack if human mentality is to progress beyond it. Not Einstein. Not Newton. Not Planck. The greatest challenger of the Fortean principle of temporary acceptance--was Gillette. For his ‘cosmic’ theory, ‘a Unitary conception of all Natural Phenomena,’ embraces, envelops and includes Orthodoxy, plus Babbit, Ouspensky, Crehore, Drayson, Graydon, Blavatsky and Page. We are unaware of any cosmogony, from Pythagorous to Voliva, which Gilette’s theory cannot assimilate. In fine, we see no reason why any of them could object to being gobbled up by anything so capacious. There is room for all--and only a few simple readjustments of focus are necessary to bring all the welter of private opinions into general accord--with Gillette.

“The remunerative researches which keep so many gainfully employed need NOT be abandoned. On the contrary, all may be continued, and a raft of new ones added. Here is the book to put a stop to World Fraud III, by using up all the steel they can make and all the mental energy the race can generate. Artists are wanted to embellish the endless charts and graphs--to glorify new loves and animosities: musicians to compose new scores for the ‘spheres.’ Here is an epoch--tailor-made--waiting to be exploited. One could write about the possibilities from now on--but, please do not misunderstand.

“Our enthusiasm for Gillette’s theory is not based upon absolute approval, but upon the challenging circumstance, unique in our experience, that we can find no flaws in it--except some minor ones regarding the terms of the author’s expression, which, doubtless, he could rectify if he were still alive.

“Nobody is going to republish this adversary for us. We must do it ourselves. We are exploring the possibilities, costs, etc., etc., with a view toward doing that as soon as the alleged paper shortage will permit. We shall have to call upon subscribers to underwrite the first complete edition.”

In the late 1940s, when Thayer contemplated a Fortean University, he thought that Gillette’s writing should form the basis of an entire department. Thayer thought it was the equivalent of cosmology, with a “unitary conception of all natural phenomena . . . a single law of nature.” Brancato was taken enough with Gillette’s ideas to send $20 to support a chair in the study of his work, which Thayer reported in Doubt 20 (March 1948). But that seems to be the last time that Brancato interacted with the Society.

Five issues later, Thayer had him listed among the “lost sheep” and was pleading with the membership to reconnect him. The only address he had for him, though, was the army in San Francisco, which made hunting him down difficult.

The last mention came a couple of years later, in Doubt 29 (July 1950)—but this was probably also the first mention. Thayer was hoping to republish Gillette’s work, which had become rare, with the Society running out of its stock. (One member had just sent some material to the Society, which made reprinting seem possible.) He was contemplating a subscription to support the work—but never came through. In the meantime, he reprinted a long and confusing letter from “MFS Brancato,” which he admitted had been sent to him in the past—likely, it seems, when Brancato gave his contribution. Brancato admitted he had not read Gillette’s entire corpus but felt the need to critique several of his points. The upshot was that Gillette’ unitary view was too limiting: that there were a whole host of phenomena that existed outside of his framework and that, indeed, Forteans were in a better position to see these anomalies that one who believed what Gillette wrote.

It was a strike for Fort, and one against Thayer’s own orthodoxy. But there was never a follow up. Brancato crossed the Fortean stream and just kept going, on to his own activities, and what he saw in Fort and Forteanism remains a mystery. That he was also connected with Cayce, though, and the search for new scientific laws puts him in the mainstream of Forteanism as it was interpreted in the late 1940s—even by mild critics like John W. Campbell. But, like a Fortean phenomena, Brancato is himself mysterious, slipping away at the crucial moment.