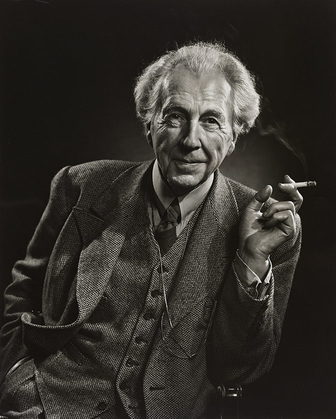

Morris Ernst (left) in court defending Gustave Flaubert's November against censorship, 1930s.

Morris Ernst (left) in court defending Gustave Flaubert's November against censorship, 1930s. Minor Forteans—Majors in their chosen professions.

In the mid- to late-1940s, Tiffany Thayer, secretary of the Fortean Society, was in an organizing mood. He’d soon enough give up on it and repudiate most of his ideas, and many of those he tried to bring into the Society’s fold, but for a fe years he was a downright evangelical Fortean. Among his organizational attempts was naming a number of so-called Accepted Fellows of the Fortean Society, AFFSes, as he would call them. These were people who were not necessarily members of the Fortean Society, but who nonetheless embodied some certain set of Fortean values.

Nominally, at least, nominations and votes came from the membership at large—and there is some evidence of that being the case, in that Thayer was not always happy with those who were proposed for Fellowship—but it is hard to say that was always the case. In part because the process was not transparent. In part because so often the nominees reflected Thayer’s particular version of what counted as Forteanism. That was the case with these three Accepted Fellows of the Fortean Society: the connections between them and Charles Fort are either so obscure as to be invisible or parallel certain of Thayer’s obsessions.

In the mid- to late-1940s, Tiffany Thayer, secretary of the Fortean Society, was in an organizing mood. He’d soon enough give up on it and repudiate most of his ideas, and many of those he tried to bring into the Society’s fold, but for a fe years he was a downright evangelical Fortean. Among his organizational attempts was naming a number of so-called Accepted Fellows of the Fortean Society, AFFSes, as he would call them. These were people who were not necessarily members of the Fortean Society, but who nonetheless embodied some certain set of Fortean values.

Nominally, at least, nominations and votes came from the membership at large—and there is some evidence of that being the case, in that Thayer was not always happy with those who were proposed for Fellowship—but it is hard to say that was always the case. In part because the process was not transparent. In part because so often the nominees reflected Thayer’s particular version of what counted as Forteanism. That was the case with these three Accepted Fellows of the Fortean Society: the connections between them and Charles Fort are either so obscure as to be invisible or parallel certain of Thayer’s obsessions.

In Doubt 15 (Summer 1946), Thayer provided a list of Accepted Fellows, among them some people discussed in earlier posts: Manly P. Hall, Norman Thomas, Albert Jay Nock, the Duke of Bedford. He also mentioned two names that do not otherwise appear in the pages of the magazine during its 20+ year run: Morris Ernst and Claude Fayette Bragdon. Then he includes a new name—a new fellow who was nominated and chosen by the membership, whom Thayer offered the fellowship, and who subsequently accepted (for there were fellows who never accepted the questionable honor). This last was Frank Lloyd Wright. All three belonged to Fort’s generation, much older than Thayer.

Born in Alabama (1888) and raised in New York by immigrant Jewish parents, Morris Ernst put himself through law school at night. In 1917, Ernst was an earl joinder of the National Civil Liberties Bureau, which opposed the Great War and assisted Conscientious Objectors. Members included other honored Forteans, Clarence Darrow and Norman Thomas. Later, the NCLB morphed into the American Civil Liberties Union. The first decades of the ACLU were spent, especially, challenging censorship laws; later, the Union took on the rights of black and Native Americans. Ernst was a general counsel for the ACLU from 1929 to 1959. During the 1930s, he took care of a number of censorship cases, including one that allowed James Joyce’s Ulysses to be published in America.

Thayer left no particular record of why Ernst was among those nominated, or how he saw the lawyer’s actions lining up with Fortean values, but it doesn’t take much to guess. As a general rule, Thayer was a fan of the ACLU and claimed to donate money to it. (Almost certainly true, I just have no more evidence than his claims.) He was vehemently opposed to censorship and would have supported any court cases making literature more free. He was also opposed to war and would have supported anyone who was a friend to Conscientious Objectors. As the Fortean Society developed, it also took up the mantle of civil rights for blacks (to a small extent) and Native Americans (to a much larger extent), especially in the person of the Native American writer Iktomi.

But Why Ernst in particular? Why then? Part of the reason could just have been dumb luck: Ernst accepted the Fellowship, especially since it required absolutely no work. Thayer may have also been inspired by Ernst’s recent books, The Best is Yet: Reflections of an Irrepressible Man (1945), a memoir that would have reminded him that Ernst’s Forteanism—in the form of defending COs—dated back so long or The First Freedom, about censorship, which had been published 7 May 1946, making it just possible that Thayer had time to read it, and correspond with Ernst. It’s also the case that Ernst kept a summer home on Nantucket. Thayer liked to vacation there—it was where he died of a fatal heart attack in 1959—and so it’s not impossible that the two men would have crossed paths there, if not also in New York City where they both lived.

Born in Alabama (1888) and raised in New York by immigrant Jewish parents, Morris Ernst put himself through law school at night. In 1917, Ernst was an earl joinder of the National Civil Liberties Bureau, which opposed the Great War and assisted Conscientious Objectors. Members included other honored Forteans, Clarence Darrow and Norman Thomas. Later, the NCLB morphed into the American Civil Liberties Union. The first decades of the ACLU were spent, especially, challenging censorship laws; later, the Union took on the rights of black and Native Americans. Ernst was a general counsel for the ACLU from 1929 to 1959. During the 1930s, he took care of a number of censorship cases, including one that allowed James Joyce’s Ulysses to be published in America.

Thayer left no particular record of why Ernst was among those nominated, or how he saw the lawyer’s actions lining up with Fortean values, but it doesn’t take much to guess. As a general rule, Thayer was a fan of the ACLU and claimed to donate money to it. (Almost certainly true, I just have no more evidence than his claims.) He was vehemently opposed to censorship and would have supported any court cases making literature more free. He was also opposed to war and would have supported anyone who was a friend to Conscientious Objectors. As the Fortean Society developed, it also took up the mantle of civil rights for blacks (to a small extent) and Native Americans (to a much larger extent), especially in the person of the Native American writer Iktomi.

But Why Ernst in particular? Why then? Part of the reason could just have been dumb luck: Ernst accepted the Fellowship, especially since it required absolutely no work. Thayer may have also been inspired by Ernst’s recent books, The Best is Yet: Reflections of an Irrepressible Man (1945), a memoir that would have reminded him that Ernst’s Forteanism—in the form of defending COs—dated back so long or The First Freedom, about censorship, which had been published 7 May 1946, making it just possible that Thayer had time to read it, and correspond with Ernst. It’s also the case that Ernst kept a summer home on Nantucket. Thayer liked to vacation there—it was where he died of a fatal heart attack in 1959—and so it’s not impossible that the two men would have crossed paths there, if not also in New York City where they both lived.

Claude Fayette Bragdon, undated photo.

Claude Fayette Bragdon, undated photo. Thayer, it seems, also had an interest in architecture, although this shows up in the people he celebrated rather than any prolonged discussion: his views on the matter I cannot suss—somewhat surprising since while he indeed seemed to have opinions on everything, he was very rarely reticent, no matter whether he knew about which he talked or not. This passion showed itself in his championing of R. Buckminster Fuller—to be considered in a different post—as well as the other two Named Fellows discusses here, Claude Fayette Bragdon and Frank Lloyd Wright.

Of the three, it is easiest to see how Bragdon came to Thayer’s attention. He nestled nicely into the confines of the Fortean Society as it developed through the 1940s. Bragdon was an architect from Rochester New York (born two years after Fort, in 1866). Deeply influenced by Theosophy—as well as the Prairie School that also produced Wright—Bragdon wrote texts on Buddhism and translated Ouspensky’s metaphysical classic Tertium Organum. He structured his architecture around numeric patterns found in nature (and metaphysics) and was also pulled toward experimenting with dimensionality—he was particularly intrigued by the fourth dimension and wrote texts on it. In later years, he also wrote on metaphysical topics such as yoga. Bragdon was an associate of John Cowper Powys, one of the early members of the Fortean Society and also a New York eccentric.

By the time that Thayer was celebrating Bragdon, he was long past his heyday. He gave up his architectural practice around World War I after a fight with George Eastman Kodak, king of Rochester, and moved to New York City, where he designed sets for plays. It is highly likely that he had read Fort, although I find no mention of Fort in his 1938 biography More Lives Than One. And, indeed, Brandon would be read by many of those who also read Fort—the photographer Clarence Laughlin, for example, the novelist Malcolm Lowry, and both were prized by N. Meade Layne’s Borderlands Science Research Association, which quoted and promoted Bragdon’s books. What prompted Thayer to reach out at this moment is unclear—maybe he had long meant to connect with someone whose name he must have come across several times; maybe, too, he worried that Bragdon was getting old and would soon pass. If that was the case, he was right, because Bragdon died in September of 1946, just a month or so after his 80th birthday. Given all of the above, though, it is little surprise that Bragdon accepted the Fellowship.

Of the three, it is easiest to see how Bragdon came to Thayer’s attention. He nestled nicely into the confines of the Fortean Society as it developed through the 1940s. Bragdon was an architect from Rochester New York (born two years after Fort, in 1866). Deeply influenced by Theosophy—as well as the Prairie School that also produced Wright—Bragdon wrote texts on Buddhism and translated Ouspensky’s metaphysical classic Tertium Organum. He structured his architecture around numeric patterns found in nature (and metaphysics) and was also pulled toward experimenting with dimensionality—he was particularly intrigued by the fourth dimension and wrote texts on it. In later years, he also wrote on metaphysical topics such as yoga. Bragdon was an associate of John Cowper Powys, one of the early members of the Fortean Society and also a New York eccentric.

By the time that Thayer was celebrating Bragdon, he was long past his heyday. He gave up his architectural practice around World War I after a fight with George Eastman Kodak, king of Rochester, and moved to New York City, where he designed sets for plays. It is highly likely that he had read Fort, although I find no mention of Fort in his 1938 biography More Lives Than One. And, indeed, Brandon would be read by many of those who also read Fort—the photographer Clarence Laughlin, for example, the novelist Malcolm Lowry, and both were prized by N. Meade Layne’s Borderlands Science Research Association, which quoted and promoted Bragdon’s books. What prompted Thayer to reach out at this moment is unclear—maybe he had long meant to connect with someone whose name he must have come across several times; maybe, too, he worried that Bragdon was getting old and would soon pass. If that was the case, he was right, because Bragdon died in September of 1946, just a month or so after his 80th birthday. Given all of the above, though, it is little surprise that Bragdon accepted the Fellowship.

Frank Lloyd Wright

Frank Lloyd Wright The hardest connection to make is between the Fortean Society and Frank Lloyd Wright. Wright, of course, is the well known architect—probably the most famous American architect—who did so much to strip away Victorian housing structures and create open floor plans, drawing from other Prairie School architects, nature, and Japanese art to create organic structures, in the same vein as Bragdon. He is perhaps most known for Taliesin in Wisconsin and Falling Water in Pennsylvania, but also designed and produced hundreds of other structures. Wright was born in 1867, three years after Fort, and died in 1959, the same year as Thayer.

Competing with his architectural ideas for newspaper space were his affairs: like Theodore Dreiser, Wright was a notorious womanizer, fathering several children with his first wife even while stepping out with another woman publicly. He was denied a divorce because his wife was sure he would come back. He never did; his mistress at the time was tragically murdered at Taliesin while it was under construction, after which time his first wife finally acceded to the divorce. Wright married again, but was again unfaithful—taking up with Olgivanna Ivanovna Lazovich, a dancer some three decades his junior, causing much furor. The two moved into Taliesin together, though each still married to other people, and Wright was even arrested under the Mann act, although charges were dropped. Eventually, but got divorces, and married each other in 1928.

Wright and Olgivanna lived in southern California, for a time, which is the most obvious connection with Forteanism. It was there that Wright may have met John Cowper Powys, while Powys was making his SoCal rounds. (At least Wright’s son, also an architect, did.) The two shared an interest in Welsh mythology,t he name Taliesin and its motto coming from Welsh legend: Taliesin the poet-magician, Y Gwir yn Erbyn y Byd meaning ‘Truth Against the World.’ Olgivanna was a follower of the mystic G. I. Gurdjieff and interested in Theosophical ideas, both enthusiasms she passed to Wright, although they became tempered in the transmission. That he may have come across the name, perhaps even the writing, of Charles Fort seems possible, given the southern California milieux. But he makes no mention of Fort in his autobiography, nor is Fort’s name brought up in any of the biographies of Wright I have seen.

And so it was that in April 1946—according to An Index to the Taliesin Correspondence, Volume 1 (a copy of which I have requested)—that Thayer wrote to Wright, noting that he had been nominated and voted a Fellow of the Fortean Society. And so it was that Wright accepted. The questions, as above, are why did Thayer make the offer then—and why did Wright accept? As to why Wright would accept—I have nothing more than vague speculation, based on his own developed interest in Theosophy and alternative modes of thought and science. The timing of the offer may have had to do with his Wright’s advancing age, or perhaps with his work on the Guggenheim building, which began in 1943. Wright’s son had published a book, My Father Who Is on Earth in March of 1946, and that may have caught Thayer’s attention—certainly the timing is about right. Thirteen years later, when Thayer wrote an obituary for Wright, he gave only a slight justification for him as a Fortean, even though he never seems to have soured on Wright the way he did other Named Fellows, other Fortean organizations, and, indeed, so many Forteans: “He used architecture as a springboard to his true life vocation which was to be the number on controversialist of all time. That was what made him the splendid Fortean he was.”

Beside the announcement of his accepting the fellowship and the brief notice of his passing, Wright made the pages of Doubt one more time—three times as often, then as either Ernst or Bragdon. But, as in all the other cases, there is no evidence that Wright was actually in communication with the Fortean Society, in sympathy with its activities, or even reading Doubt. The mention came as part of a news item that Thayer himself had found, and was using to comment on Joseph McCarthy, the Republican Senator from Wisconsin and leading agitator against Communism in American government. Writing in 1955, after a failed recall attempt, McCarthy’s censure by the Senate, and two years before his death, Thayer said (Doubt 16 Summer 1946, the issue after Wright’s Fellowship acceptance was announced): “Accepted Fellow Fortean Society, Frank Lloyd Wright, says he’s going to take the roof off Taliesin and move out of Wisconsin because the supreme court of that State disallowed his claim for tax-exemption as a school. We could give him another good reason for leaving the State, but that will probably rectify itself at the next Senatorial election.”

As in other cases of big-named Forteans, the connections between the celebrities and the Society say more about the Society, and how it wanted to be seen, than the views of the Accepted Fellows. So, yes, Morris Ernst, Claude Bragdon, and Frank Lloyd Wright all accepted Fellowship with the Society—an honor that required no payment, no work—but they were hardly more than members in name only, and their enthusiasm for the works of Charles Fort muted at best, more probably close to, if not exactly, non-existent.

PS: I have since seen Thayer's letter offering Fellowship to Wright, and Wright's acceptance. The letter was generic, and included a pamphlet on the Society as well as an offer to send the books. Wright said he was "quite willing to be Fortified if you say so" and asked that Fort's books be sent. He had heard of the man, but had not read him,. and was curious. So, it seems, Wright accepted becoming a Named Fellow purely as a flyer and had no real experience with Forteanism. 1/30/15.

Competing with his architectural ideas for newspaper space were his affairs: like Theodore Dreiser, Wright was a notorious womanizer, fathering several children with his first wife even while stepping out with another woman publicly. He was denied a divorce because his wife was sure he would come back. He never did; his mistress at the time was tragically murdered at Taliesin while it was under construction, after which time his first wife finally acceded to the divorce. Wright married again, but was again unfaithful—taking up with Olgivanna Ivanovna Lazovich, a dancer some three decades his junior, causing much furor. The two moved into Taliesin together, though each still married to other people, and Wright was even arrested under the Mann act, although charges were dropped. Eventually, but got divorces, and married each other in 1928.

Wright and Olgivanna lived in southern California, for a time, which is the most obvious connection with Forteanism. It was there that Wright may have met John Cowper Powys, while Powys was making his SoCal rounds. (At least Wright’s son, also an architect, did.) The two shared an interest in Welsh mythology,t he name Taliesin and its motto coming from Welsh legend: Taliesin the poet-magician, Y Gwir yn Erbyn y Byd meaning ‘Truth Against the World.’ Olgivanna was a follower of the mystic G. I. Gurdjieff and interested in Theosophical ideas, both enthusiasms she passed to Wright, although they became tempered in the transmission. That he may have come across the name, perhaps even the writing, of Charles Fort seems possible, given the southern California milieux. But he makes no mention of Fort in his autobiography, nor is Fort’s name brought up in any of the biographies of Wright I have seen.

And so it was that in April 1946—according to An Index to the Taliesin Correspondence, Volume 1 (a copy of which I have requested)—that Thayer wrote to Wright, noting that he had been nominated and voted a Fellow of the Fortean Society. And so it was that Wright accepted. The questions, as above, are why did Thayer make the offer then—and why did Wright accept? As to why Wright would accept—I have nothing more than vague speculation, based on his own developed interest in Theosophy and alternative modes of thought and science. The timing of the offer may have had to do with his Wright’s advancing age, or perhaps with his work on the Guggenheim building, which began in 1943. Wright’s son had published a book, My Father Who Is on Earth in March of 1946, and that may have caught Thayer’s attention—certainly the timing is about right. Thirteen years later, when Thayer wrote an obituary for Wright, he gave only a slight justification for him as a Fortean, even though he never seems to have soured on Wright the way he did other Named Fellows, other Fortean organizations, and, indeed, so many Forteans: “He used architecture as a springboard to his true life vocation which was to be the number on controversialist of all time. That was what made him the splendid Fortean he was.”

Beside the announcement of his accepting the fellowship and the brief notice of his passing, Wright made the pages of Doubt one more time—three times as often, then as either Ernst or Bragdon. But, as in all the other cases, there is no evidence that Wright was actually in communication with the Fortean Society, in sympathy with its activities, or even reading Doubt. The mention came as part of a news item that Thayer himself had found, and was using to comment on Joseph McCarthy, the Republican Senator from Wisconsin and leading agitator against Communism in American government. Writing in 1955, after a failed recall attempt, McCarthy’s censure by the Senate, and two years before his death, Thayer said (Doubt 16 Summer 1946, the issue after Wright’s Fellowship acceptance was announced): “Accepted Fellow Fortean Society, Frank Lloyd Wright, says he’s going to take the roof off Taliesin and move out of Wisconsin because the supreme court of that State disallowed his claim for tax-exemption as a school. We could give him another good reason for leaving the State, but that will probably rectify itself at the next Senatorial election.”

As in other cases of big-named Forteans, the connections between the celebrities and the Society say more about the Society, and how it wanted to be seen, than the views of the Accepted Fellows. So, yes, Morris Ernst, Claude Bragdon, and Frank Lloyd Wright all accepted Fellowship with the Society—an honor that required no payment, no work—but they were hardly more than members in name only, and their enthusiasm for the works of Charles Fort muted at best, more probably close to, if not exactly, non-existent.

PS: I have since seen Thayer's letter offering Fellowship to Wright, and Wright's acceptance. The letter was generic, and included a pamphlet on the Society as well as an offer to send the books. Wright said he was "quite willing to be Fortified if you say so" and asked that Fort's books be sent. He had heard of the man, but had not read him,. and was curious. So, it seems, Wright accepted becoming a Named Fellow purely as a flyer and had no real experience with Forteanism. 1/30/15.