Enmeshed with Forteanism or aware of Fort as an expression of modernist literature—they took a stand against Forteans.

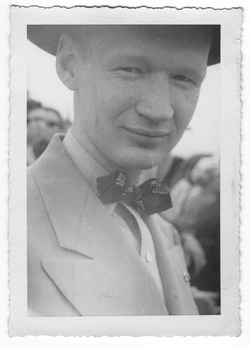

John Bristol—Jack—Speer was born 9 August 1920 in Comanche, Oklahoma. He was the second of four children. His mother was Louise; his father, James, was an attorney. Jack attended George Washington University and worked as a file clerk. His education was interrupted by World War II—he went to work for the Lend Lease Administration—then followed in his father’s footsteps, receiving a law degree from the University of Washington. He settled in the Pacific Northwest, marrying Myrtle Cox in 1951.

Speer belonged to the first generation of science fiction fans, coming to the genre in the mid-1930s. In 1939, not even yet twenty, he published the first history of fandom, “Up to Now” (in which he established the generations of fanhood.) Active with amateur fanzines, he introduced the practice of sending comments to other ‘zines. In 1940, he wrote science fiction songs, which were then handed out at the world convention that year (in Chicago). He was an editor of the National Fantasy Fan Federation and perpetrated seminal hoaxes, practical jokes becoming a part of fannish folk life. In 1944, he codified fan language in an encyclopedia.

John Bristol—Jack—Speer was born 9 August 1920 in Comanche, Oklahoma. He was the second of four children. His mother was Louise; his father, James, was an attorney. Jack attended George Washington University and worked as a file clerk. His education was interrupted by World War II—he went to work for the Lend Lease Administration—then followed in his father’s footsteps, receiving a law degree from the University of Washington. He settled in the Pacific Northwest, marrying Myrtle Cox in 1951.

Speer belonged to the first generation of science fiction fans, coming to the genre in the mid-1930s. In 1939, not even yet twenty, he published the first history of fandom, “Up to Now” (in which he established the generations of fanhood.) Active with amateur fanzines, he introduced the practice of sending comments to other ‘zines. In 1940, he wrote science fiction songs, which were then handed out at the world convention that year (in Chicago). He was an editor of the National Fantasy Fan Federation and perpetrated seminal hoaxes, practical jokes becoming a part of fannish folk life. In 1944, he codified fan language in an encyclopedia.

Speer continued his fan-related activities all of his life. He was also a photographer, a game inventor, and a parliamentarian. He was a Democratic politician in Washington from 1959 to 1961. The following year, he, Myrtle, and their two children relocated to New Mexico. A full life, then, beyond his glancing appearance in Fortean history.

Jack Speer died 28 June 2008, aged 87.

*************************************

Speer became aware of Charles Fort, Forteans, and their Society from reading science fiction, although the exact date and exact reference is unknown to me. His 1944 definition of “Forteanism” from his encyclopedia is mostly straightforward: “The beliefs advance by Charles Fort in his books, of which Lo! was published serially in Astounding. The main idea is that modern science is a tissue of outworn saws, holes continually appearing in it and being patched up or glossed over by new explanations. Fort compiled a great mass of unexplained occurrences, such as the well-known mystery of the Marie Celeste. In arranging and commenting on them, he seemed to be maintaining, among other theories, that the Earth is visited and considered as properly by superior beings (now called vitons); that there is a power of matter-transmission which he calls teleportation being evidenced from time to time, as by showers of objets from within a room near its ceiling; and that the Earth is surrounded by a shell not far away, the planets and stars being eruptions on the shell similar to volcanoes.”

One does detect the whiff of displeasure, though. Part of that is reducing Forteanism to a set of beliefs, rather than a mode of attention—to the anomalous—or philosophical orientation—of skepticism; there’s also the blending of fact and fiction, referring to Fort’s superior beings by the name that Eric Frank Russell gave to such creatures in his novel “Sinister Barrier.” In this case, straightforward description and simple linkages does not do justice to the morass of overlapping ideas that constituted Forteanism and were held by Forteans—beliefs that were often in conflict with each other, with Thayer, and with the Fort himself.

Two years later, Speer made himself plain, writing to Donn Brazier, a Fortean who was then putting out the ‘zine “Ember.” In issue 20 (dated 3 November 1946), a letter Speer wrote is quoted: “On the Fortean material i’m (sic) afraid my reaction will be much the same as Harry Warner’s detailed in the last Horizons. This affects my reception of Ember, too. As i’ve stated in FAPA, I don’t think the energy spent in digging up and publishing odd fragments of all sorts does much good, and the time were better spent in systematic study and research. (This is a hobby, old man, not my ‘life’s work’.) However, as Ember takes on a more general character, it has quite a bit of materials that interests me.” He went on to call out specific problems he saw in Fortean theses, and in Forteans themselves. Talk of the so-called Oregon Vortex—a fun house that was intercepted by some as the product of unknown forces—was bunk, he said; whirlwinds could not lift frogs and rain them down again. (The implication being not that there was some other force, but that the reports themselves were false.) He thought that Thayer was superficial, and he was annoyed by one of the Fortean Society’s recent poster-boys, Robert L. Farnsworth: Speer distrusted his flag-waving nationalism.

Unfortunately, I have not been able to track down what he wrote in FAPA, the Fantasy Amateur Press Association. But I did find one other contribution Speer made to Fortean thought, which does qualify his attacks somewhat. At least, I think this is Speer’s contribution. That surname appears once in “Doubt,” from much later, in the 1950s, suggesting perhaps that Speer mellowed in his estimation, or, at the very least, continued to keep tabs on Forteanism and felt some impulse to contribute.

The appearance of the name Speer is in Doubt 44, from April 1954. It’s impossible to tie the acknowledgment to any particular report, but the name appeared at the end of a column Thayer wrote pointing out the faults of “safety glass” and the tendency of windshields to break for no apparent reason. Was Speer, then, despite his reservations, nonetheless a member of the Society—an anti-Fortean in its midst? Or was this some other person named Speer?

********************************

Jack Speer died 28 June 2008, aged 87.

*************************************

Speer became aware of Charles Fort, Forteans, and their Society from reading science fiction, although the exact date and exact reference is unknown to me. His 1944 definition of “Forteanism” from his encyclopedia is mostly straightforward: “The beliefs advance by Charles Fort in his books, of which Lo! was published serially in Astounding. The main idea is that modern science is a tissue of outworn saws, holes continually appearing in it and being patched up or glossed over by new explanations. Fort compiled a great mass of unexplained occurrences, such as the well-known mystery of the Marie Celeste. In arranging and commenting on them, he seemed to be maintaining, among other theories, that the Earth is visited and considered as properly by superior beings (now called vitons); that there is a power of matter-transmission which he calls teleportation being evidenced from time to time, as by showers of objets from within a room near its ceiling; and that the Earth is surrounded by a shell not far away, the planets and stars being eruptions on the shell similar to volcanoes.”

One does detect the whiff of displeasure, though. Part of that is reducing Forteanism to a set of beliefs, rather than a mode of attention—to the anomalous—or philosophical orientation—of skepticism; there’s also the blending of fact and fiction, referring to Fort’s superior beings by the name that Eric Frank Russell gave to such creatures in his novel “Sinister Barrier.” In this case, straightforward description and simple linkages does not do justice to the morass of overlapping ideas that constituted Forteanism and were held by Forteans—beliefs that were often in conflict with each other, with Thayer, and with the Fort himself.

Two years later, Speer made himself plain, writing to Donn Brazier, a Fortean who was then putting out the ‘zine “Ember.” In issue 20 (dated 3 November 1946), a letter Speer wrote is quoted: “On the Fortean material i’m (sic) afraid my reaction will be much the same as Harry Warner’s detailed in the last Horizons. This affects my reception of Ember, too. As i’ve stated in FAPA, I don’t think the energy spent in digging up and publishing odd fragments of all sorts does much good, and the time were better spent in systematic study and research. (This is a hobby, old man, not my ‘life’s work’.) However, as Ember takes on a more general character, it has quite a bit of materials that interests me.” He went on to call out specific problems he saw in Fortean theses, and in Forteans themselves. Talk of the so-called Oregon Vortex—a fun house that was intercepted by some as the product of unknown forces—was bunk, he said; whirlwinds could not lift frogs and rain them down again. (The implication being not that there was some other force, but that the reports themselves were false.) He thought that Thayer was superficial, and he was annoyed by one of the Fortean Society’s recent poster-boys, Robert L. Farnsworth: Speer distrusted his flag-waving nationalism.

Unfortunately, I have not been able to track down what he wrote in FAPA, the Fantasy Amateur Press Association. But I did find one other contribution Speer made to Fortean thought, which does qualify his attacks somewhat. At least, I think this is Speer’s contribution. That surname appears once in “Doubt,” from much later, in the 1950s, suggesting perhaps that Speer mellowed in his estimation, or, at the very least, continued to keep tabs on Forteanism and felt some impulse to contribute.

The appearance of the name Speer is in Doubt 44, from April 1954. It’s impossible to tie the acknowledgment to any particular report, but the name appeared at the end of a column Thayer wrote pointing out the faults of “safety glass” and the tendency of windshields to break for no apparent reason. Was Speer, then, despite his reservations, nonetheless a member of the Society—an anti-Fortean in its midst? Or was this some other person named Speer?

********************************

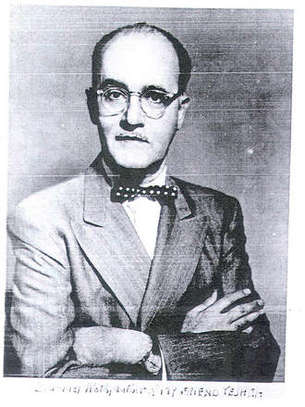

Harry Backer Warner, Jr., was Speer’s contemporary and another historian of science fiction. Born 19 December 1922 in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, Harry was the son of the former Margaret C. Klipp and Harry B. Warner, a bookkeeper. By 1930 the family had relocated to Hagerstown, Maryland, where the elder Harry worked for a confectionary store. Harry dropped out of school early, apparently because of illness. In 1943, he went to work for the Hagerstown Herald-Mail, where he would remain for the next four decades. He taught himself seven languages, and during World War II translated letters from Dutch and German families to the families of soldiers.

Like Speer, Warner came to science fiction during the 1930s, and became active early. In 1938 he used a mimeograph machine to produce his first ‘zine “Spaceways.” About a year later, he started a more personal ‘zine, “Horizons,” which recorded his opinion on important matters of the day. “Spaceways” ran four years”; “Horizons,” sixty-four, with barely an interruption. “Horizons was distributed through FAPA. In 1969, he wrote the (informal) history of science fiction fandom, “All Our Yesterdays.” Later he wrote a sequel of sorts, “A Wealth of Fable.” By accounts, he kept his journalism world and science fiction worlds separate—his newspaper colleagues were surprised to learn of his avocation posthumously.

Harry Warner died 17 February 2003, aged 80.

***************************

Although his writings are generally better known and more accessible, I have found mostly second-hand references of his ideas about Fort and Forteanism. As with Speer, it’s clear that his connection to Forteanism was by necessity: other fans brought Fort, his ideas, and the Society, into ‘zines, and Warner was forced to reckon with the topic. But he apparently did not see much value in it—though he was open minded and accepting.

In the eighth issue of “Spaceways”—October 1939—Warner published Russell’s essay “Fort the Colossus.” That same issue contained a review of Russell’s “Sinister Barrier,” by Jack Chapman Miske (writing as Star Treader), which claimed the Russell had appropriated Fort’s style, and then debunked some of the anomalies that Fort presented: “Absurdity after absurdity, superstition after superstition. I would be the last to dogmatically state that all of Fort’s findings, to so call them, are erroneous, but certainly the bulk of them have no more truth to them than stories of ghosts, ghouls, vampires, and similar famous but non-existent phenomena.” Like Speer, Miske conflated fictional extensions of Fort with Fort himself, seeing the paratext that Russel included in “Sinister Barrier,” which purported that Fort’s theories were genuinely true, as an authentic expression of Russell’s now beliefs.

Continuing directly from the earlier quote, he wrote, “And, at any rate, Russell himself has twice dealt killing blows to his own beliefs—but Russell does believe these ‘blue balls’ do exist and do rule Earth. According to his story, all persons who discover the secret truth about these ‘masters of Earth’ are killed or spirited away before they can disclose it. Russell, however, did a very thorough job of telling all about it, and I believe he’s at this very moment touring the U.S., in fine health indeed. And I see no evidence of the carnage that should have resulted when all the readers of UNKNOWN learned the secret. And now, the crowning glory, Russell has just set about, equally earnestly, to prove that Earth not only has been visited by inhabitants of other worlds, but that we are, continuously! Tell this poor, bewildered one, Eric, sweet, don’t your two contentions contradict just a wee, little bit?”

Russell responded in the first issue of the second volume, dated the next month, November 1939. He said that he only wished he could write in Fort’s style; he admitted that some of Fort’s tales had been debunked, but others not, and that Star Treader needed to be more careful. He also addressed the inconsistency Miske had pointed out, maintaining the stance that he really did believe his theories. (This seems unlikely, but I guess it could be true; more likely is that Russell was continuing his gag.) He said that he had news clippings about the blue lights, attesting to their veracity. And as for his ability to convey the truth, when others who had come to it were dispatched, he said in the story itself that the system was breaking down—and so the actions of the powers-that-be were becoming apparent.

The review was not Warner’s and cannot be strictly attributed to him. After all, he also published Russell’s essay, which took a diametrically opposed view. But the evidence suggests that Warner was on Mike’s side, not Russell’s, though I can only see this evidence tangentially—from Speer’s letter to Donn P. Brazier. I have not been able to read Warner’s issue of “Horizons” that took exception to Fort. But it is clear that Warner was no fan of Fort or Forteans. To my knowledge, he never appeared in the magazine “Doubt.

It is worth noting that some other prominent fans had little interest in the Fortean Society, among them Forest Ackerman, or Forry (or 4-E). For those trying to make science fiction respectable, Fortean topics, like the Shaver mystery, were something of an embarrassment. Or so I imagine. It would be my guess that this concern over Forteanism’s paranormal connections, as well as the assumed credulity of Forteans and the impossibility of some of the anomalies, made Warner unsympathetic to the topic.

*****************************************************

Like Speer, Warner came to science fiction during the 1930s, and became active early. In 1938 he used a mimeograph machine to produce his first ‘zine “Spaceways.” About a year later, he started a more personal ‘zine, “Horizons,” which recorded his opinion on important matters of the day. “Spaceways” ran four years”; “Horizons,” sixty-four, with barely an interruption. “Horizons was distributed through FAPA. In 1969, he wrote the (informal) history of science fiction fandom, “All Our Yesterdays.” Later he wrote a sequel of sorts, “A Wealth of Fable.” By accounts, he kept his journalism world and science fiction worlds separate—his newspaper colleagues were surprised to learn of his avocation posthumously.

Harry Warner died 17 February 2003, aged 80.

***************************

Although his writings are generally better known and more accessible, I have found mostly second-hand references of his ideas about Fort and Forteanism. As with Speer, it’s clear that his connection to Forteanism was by necessity: other fans brought Fort, his ideas, and the Society, into ‘zines, and Warner was forced to reckon with the topic. But he apparently did not see much value in it—though he was open minded and accepting.

In the eighth issue of “Spaceways”—October 1939—Warner published Russell’s essay “Fort the Colossus.” That same issue contained a review of Russell’s “Sinister Barrier,” by Jack Chapman Miske (writing as Star Treader), which claimed the Russell had appropriated Fort’s style, and then debunked some of the anomalies that Fort presented: “Absurdity after absurdity, superstition after superstition. I would be the last to dogmatically state that all of Fort’s findings, to so call them, are erroneous, but certainly the bulk of them have no more truth to them than stories of ghosts, ghouls, vampires, and similar famous but non-existent phenomena.” Like Speer, Miske conflated fictional extensions of Fort with Fort himself, seeing the paratext that Russel included in “Sinister Barrier,” which purported that Fort’s theories were genuinely true, as an authentic expression of Russell’s now beliefs.

Continuing directly from the earlier quote, he wrote, “And, at any rate, Russell himself has twice dealt killing blows to his own beliefs—but Russell does believe these ‘blue balls’ do exist and do rule Earth. According to his story, all persons who discover the secret truth about these ‘masters of Earth’ are killed or spirited away before they can disclose it. Russell, however, did a very thorough job of telling all about it, and I believe he’s at this very moment touring the U.S., in fine health indeed. And I see no evidence of the carnage that should have resulted when all the readers of UNKNOWN learned the secret. And now, the crowning glory, Russell has just set about, equally earnestly, to prove that Earth not only has been visited by inhabitants of other worlds, but that we are, continuously! Tell this poor, bewildered one, Eric, sweet, don’t your two contentions contradict just a wee, little bit?”

Russell responded in the first issue of the second volume, dated the next month, November 1939. He said that he only wished he could write in Fort’s style; he admitted that some of Fort’s tales had been debunked, but others not, and that Star Treader needed to be more careful. He also addressed the inconsistency Miske had pointed out, maintaining the stance that he really did believe his theories. (This seems unlikely, but I guess it could be true; more likely is that Russell was continuing his gag.) He said that he had news clippings about the blue lights, attesting to their veracity. And as for his ability to convey the truth, when others who had come to it were dispatched, he said in the story itself that the system was breaking down—and so the actions of the powers-that-be were becoming apparent.

The review was not Warner’s and cannot be strictly attributed to him. After all, he also published Russell’s essay, which took a diametrically opposed view. But the evidence suggests that Warner was on Mike’s side, not Russell’s, though I can only see this evidence tangentially—from Speer’s letter to Donn P. Brazier. I have not been able to read Warner’s issue of “Horizons” that took exception to Fort. But it is clear that Warner was no fan of Fort or Forteans. To my knowledge, he never appeared in the magazine “Doubt.

It is worth noting that some other prominent fans had little interest in the Fortean Society, among them Forest Ackerman, or Forry (or 4-E). For those trying to make science fiction respectable, Fortean topics, like the Shaver mystery, were something of an embarrassment. Or so I imagine. It would be my guess that this concern over Forteanism’s paranormal connections, as well as the assumed credulity of Forteans and the impossibility of some of the anomalies, made Warner unsympathetic to the topic.

*****************************************************

Samuel Roth was born 1893 or 1894 in Galicia—what is now Poland. His family moved to New York just round the turn of the century. Samuel went to work at a very young age, holding small jobs—peddler, newsboy, baker. His youth was disrupted, a job at the New York Globe evaporating and leaving him homeless; him continuing to scrabble, even doing a year at Columbia. He opened a bookstore, and put out a small magazine. He adopted the name of a Hungarian writer. Roth was bitten by the literature bug.

Roth wrote poetry. Some of it published Mencken’s “Smart Set” (perhaps) and “Poetry: Chicago” (for certain). He knew Carl van Doren, Maxwell Bodenheim, and Luis Zukofsky. He published William Rose Benét, Archibald MacLeish, and D. H. Lawrence. He went to London to interview literary celebrities after the war, then returned to teach English to new immigrants. Leo Hamalian’s account makes it clear that Roth was something of a daredevil publisher from the beginning: he had little scruple about pirating works, about not paying authors, and about selling pornography. He also wrote books of his own, and continued to write for magazines. He published new magazines of his own, some of them famously pirating bowdlerized versions of Joyce.

Roth continued to publish, some works pirated—T. S. Eliot—others not. He came to the attention of postal inspectors and went to jail, where he wrote a book of miscellany “Stone Walls Do Not.” Outside, he returned to pirating—in this case, D. H. Lawrence. He published an “unauthorized” biography of Herbert Hoover that alleged corruption and when that was stopped through legal machinations, a paraphrase of it. There were other such inventions as well as books on masturbation and collections of erotic tales. He was sent to jail again for his pornographic sales. While imprisoned, he ran a school for writers. Outside, there were more piracies and obscenities—some of the histories behind them as baroque enough for a post-modern literary detective novel—and, as a result, another period spent in jail.

Despite the literary names, the salacious details, the convoluted connections, it all starts to become a bore—repetition. Even his tangential relation to the Alger Hiss case reads as more of the same. What Hamalian calls “The Underside of Modern Letters” was as much a business as the glossy up-side and even its shaggy Bohemian side. In the mid-1950s, he was again swept up into a court case on obscenity, and this one landed before the Supreme Court: Roth v. United States (1957). The decision itself was a mess—formally against Roth, but with several concurrent opinions. And, in the end, it was the minority opinion that became a precedent in later decades for breaking down America’s puritanical obscenity laws.

Samuel Roth died 3 July 1974. No one was sure of his exact age, not even him.

**********************************

Samuel Roth’s involvement with Forteanism was an outgrowth of his consuming and repurposing modernist literature—in bowdlerized, paraphrased, or pirated versions. Fort he paraphrased in a 1945 book, “Peep-Hole of the Present: An Inquiry into the Substance of Appearance.” The book was put out by “Philosophical Book-Club”—perhaps an invention of Roth himself, but it points toward his pretension either way. Hamalian, though, characterizes “Peep-Hole” as science fiction, and it was in a science-fictional context that I became aware of it. I still have not read the book myself.

Hamalian simultaneously characterizes and dismisses the book—for an article published in 1974—as “nothing less than an attempt ‘to revolutionize the conception of matter as well as the prevailing conception of the size and shape of the world as a whole.’ This baroque mix of metaphysics and fantasy is dedicated to Albert Einstein, who probably did not understand any better than other bewildered readers the senescent spiritualism of a preface presumably written by Sir Arthur Eddington shortly before his death in1944. Another possibility too obvious to mention requires us to envision Roth as an astronomer—or at least as an astrologer. It only remains for him to be discovered by today’s occult freaks.”

A more sympathetic account comes from Jay A. Gertzman’s “Infamous Modernist.” Roth apparently had a mystical streak—he was unashamed of his Jewish identity, and so upset by the failure of other Jews to stand up for him that he penned a bitter book that was embraced by Nazis and continues to be used by right-wing anti-Semites—and thought that there was a “True World” composed of a substance behind the mundane one—the Mind of God behind the world of appearances. It was a kind of Platonism, then, or reflected the Kantian division between noumenal and phenomenal. Gertzman sees a connection with maverick Theosophist (and founder of Anthroposophy) Rudolf Steiner. But even Gertzman acknowledges the book was incredibly dense and difficult to make sense of.

The Peep-Hole of which Roth speaks—a word, Gertzman notes, chosen for its salacious connotation—is the mode through which humans can escape the capitalist materialism and glimpse the true world. Presumably, Fort might be something that can prepare the mind to look through the Peep-Hole, or might even be a person of the Peep-Hole—the damned facts behind scientific materialism—but Roth did not think so. For him, Fort could be entertaining, but was otherwise nothing more than invention—a good story, but unconnected to the True World. Fort, then, was part of the world of appearances. As far as I can tell, Fort’s appearance in “Peep-Hole” was the only time that Roth would write about him—Fort was something to be cannibalized in his devouring of modernism and recreating of it in his own philosophy, but only a minor thing; it’s proof of Fort’s place in the modernist canon, but Roth himself had very little to no interest in Fort, and most of that was in the service of dismissing him.

Roth’s book came to the attention of at least one science fiction fan. This is where I found the connection between Roth and Forteanism in the first place. Donn Brazier had a ‘zine called “Googol.” (He had other ‘zines, too, “Frontier,” which was explicitly Fortean, and “Embers” which was more oriented around science fiction fandom.) Googol was published in 1946. The first issue included a review of “Peep-Hole.” Brazier reflected the most promising views of the book, incomprehensible as a cohesive work, it nonetheless had intriguing ideas. He wrote,

“The book, for the most part incomprehensible, has its interesting thoughts and ideas scattered in a discussion of such things as space, consciousness, size of the world, memory, extra-dimensions, creatures of space, Godhead, eternal present, and imagination.”

…”What does Roth have to say about Fort? He describes the Henry Holt edition of Fort’s works as ‘. . . a fascinating quadruple hodgepodge of curiousa, fact, doubt, divination and deliberate drivel written in such a state of fire, fury and fine rage that going through it was an experience as delightfully escapist as the reading of a carefully planned detective story.’ And ‘The book appears to have no other ambition than to establish before man and beast that the life they belong to exhibits not a trace of plan, scheme or motive.’”

Brazier concluded, “If you come to this book cold, you’ll go away no warmer; but if are a browser [sic] in the works of the men listed in the first paragraph [Einstein, Eddington, Russell, Poincare, James, Lodge, Dunne, Ouspensky, Hinton, and Fort], you will find here a real intellectual treat. It takes more than eyes to look through the peephole.

Roth might dismiss Fort as pure entertainment, but the Fortean could, in turn, appropriate Roth, dissect him, and fit him into his own views. Perhaps this was the circle with no end and no beginning that Fort mentioned—“One measures a circle, beginning anywhere”—modernism as ouroboros, endlessly eating itself.

Roth wrote poetry. Some of it published Mencken’s “Smart Set” (perhaps) and “Poetry: Chicago” (for certain). He knew Carl van Doren, Maxwell Bodenheim, and Luis Zukofsky. He published William Rose Benét, Archibald MacLeish, and D. H. Lawrence. He went to London to interview literary celebrities after the war, then returned to teach English to new immigrants. Leo Hamalian’s account makes it clear that Roth was something of a daredevil publisher from the beginning: he had little scruple about pirating works, about not paying authors, and about selling pornography. He also wrote books of his own, and continued to write for magazines. He published new magazines of his own, some of them famously pirating bowdlerized versions of Joyce.

Roth continued to publish, some works pirated—T. S. Eliot—others not. He came to the attention of postal inspectors and went to jail, where he wrote a book of miscellany “Stone Walls Do Not.” Outside, he returned to pirating—in this case, D. H. Lawrence. He published an “unauthorized” biography of Herbert Hoover that alleged corruption and when that was stopped through legal machinations, a paraphrase of it. There were other such inventions as well as books on masturbation and collections of erotic tales. He was sent to jail again for his pornographic sales. While imprisoned, he ran a school for writers. Outside, there were more piracies and obscenities—some of the histories behind them as baroque enough for a post-modern literary detective novel—and, as a result, another period spent in jail.

Despite the literary names, the salacious details, the convoluted connections, it all starts to become a bore—repetition. Even his tangential relation to the Alger Hiss case reads as more of the same. What Hamalian calls “The Underside of Modern Letters” was as much a business as the glossy up-side and even its shaggy Bohemian side. In the mid-1950s, he was again swept up into a court case on obscenity, and this one landed before the Supreme Court: Roth v. United States (1957). The decision itself was a mess—formally against Roth, but with several concurrent opinions. And, in the end, it was the minority opinion that became a precedent in later decades for breaking down America’s puritanical obscenity laws.

Samuel Roth died 3 July 1974. No one was sure of his exact age, not even him.

**********************************

Samuel Roth’s involvement with Forteanism was an outgrowth of his consuming and repurposing modernist literature—in bowdlerized, paraphrased, or pirated versions. Fort he paraphrased in a 1945 book, “Peep-Hole of the Present: An Inquiry into the Substance of Appearance.” The book was put out by “Philosophical Book-Club”—perhaps an invention of Roth himself, but it points toward his pretension either way. Hamalian, though, characterizes “Peep-Hole” as science fiction, and it was in a science-fictional context that I became aware of it. I still have not read the book myself.

Hamalian simultaneously characterizes and dismisses the book—for an article published in 1974—as “nothing less than an attempt ‘to revolutionize the conception of matter as well as the prevailing conception of the size and shape of the world as a whole.’ This baroque mix of metaphysics and fantasy is dedicated to Albert Einstein, who probably did not understand any better than other bewildered readers the senescent spiritualism of a preface presumably written by Sir Arthur Eddington shortly before his death in1944. Another possibility too obvious to mention requires us to envision Roth as an astronomer—or at least as an astrologer. It only remains for him to be discovered by today’s occult freaks.”

A more sympathetic account comes from Jay A. Gertzman’s “Infamous Modernist.” Roth apparently had a mystical streak—he was unashamed of his Jewish identity, and so upset by the failure of other Jews to stand up for him that he penned a bitter book that was embraced by Nazis and continues to be used by right-wing anti-Semites—and thought that there was a “True World” composed of a substance behind the mundane one—the Mind of God behind the world of appearances. It was a kind of Platonism, then, or reflected the Kantian division between noumenal and phenomenal. Gertzman sees a connection with maverick Theosophist (and founder of Anthroposophy) Rudolf Steiner. But even Gertzman acknowledges the book was incredibly dense and difficult to make sense of.

The Peep-Hole of which Roth speaks—a word, Gertzman notes, chosen for its salacious connotation—is the mode through which humans can escape the capitalist materialism and glimpse the true world. Presumably, Fort might be something that can prepare the mind to look through the Peep-Hole, or might even be a person of the Peep-Hole—the damned facts behind scientific materialism—but Roth did not think so. For him, Fort could be entertaining, but was otherwise nothing more than invention—a good story, but unconnected to the True World. Fort, then, was part of the world of appearances. As far as I can tell, Fort’s appearance in “Peep-Hole” was the only time that Roth would write about him—Fort was something to be cannibalized in his devouring of modernism and recreating of it in his own philosophy, but only a minor thing; it’s proof of Fort’s place in the modernist canon, but Roth himself had very little to no interest in Fort, and most of that was in the service of dismissing him.

Roth’s book came to the attention of at least one science fiction fan. This is where I found the connection between Roth and Forteanism in the first place. Donn Brazier had a ‘zine called “Googol.” (He had other ‘zines, too, “Frontier,” which was explicitly Fortean, and “Embers” which was more oriented around science fiction fandom.) Googol was published in 1946. The first issue included a review of “Peep-Hole.” Brazier reflected the most promising views of the book, incomprehensible as a cohesive work, it nonetheless had intriguing ideas. He wrote,

“The book, for the most part incomprehensible, has its interesting thoughts and ideas scattered in a discussion of such things as space, consciousness, size of the world, memory, extra-dimensions, creatures of space, Godhead, eternal present, and imagination.”

…”What does Roth have to say about Fort? He describes the Henry Holt edition of Fort’s works as ‘. . . a fascinating quadruple hodgepodge of curiousa, fact, doubt, divination and deliberate drivel written in such a state of fire, fury and fine rage that going through it was an experience as delightfully escapist as the reading of a carefully planned detective story.’ And ‘The book appears to have no other ambition than to establish before man and beast that the life they belong to exhibits not a trace of plan, scheme or motive.’”

Brazier concluded, “If you come to this book cold, you’ll go away no warmer; but if are a browser [sic] in the works of the men listed in the first paragraph [Einstein, Eddington, Russell, Poincare, James, Lodge, Dunne, Ouspensky, Hinton, and Fort], you will find here a real intellectual treat. It takes more than eyes to look through the peephole.

Roth might dismiss Fort as pure entertainment, but the Fortean could, in turn, appropriate Roth, dissect him, and fit him into his own views. Perhaps this was the circle with no end and no beginning that Fort mentioned—“One measures a circle, beginning anywhere”—modernism as ouroboros, endlessly eating itself.