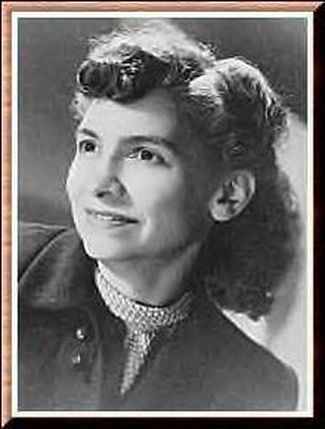

Vashti McCollum

Vashti McCollum Tiffany Thayer liked to buttress the credibility of Forteanism by inviting famous people to join. It was one of the Society’s contradictions, rejecting the mainstream even as it craved its accolades and fanfare.

Vashti McCollum was (née Cromwell) was a New Yorker, born 6 November 1912. She attended Cornell University before transferring to the University of Illinois. She graduated a,d there met her husband, John McCollum. The couple were married in 1933. They had three children. In 1944, when their eldest child, James, entered fourth grade, he came home with a form that essentially mandated ‘voluntary’ religious instruction. James was allowed to attend, until his parents became upset but he content of the class. After back and forth with the school district, Vashti filed suit, in July 1945. The trial was difficult, and life for the McCollums was difficult, too, as they were harassed in their home town. Eventually, the case made its way to the United States Supreme Court. On 8 March 1948, the court ruled that the school’s religious program was unconstitutional.

McCollum became a minor celebrity int he wake of the court case, a defender of humanism, skepticism, and civil liberties against the tyrannies of religion and the state. She became associated with Edwin Wilson’s American Humanist Association (he was a Fortean, too) and served two terms as its president. After her children finished school, she earned a master’s degree and became a world traveller. In 1953, she published a book about her struggle, “One Woman’s Fight.”

Vashti McCollum died 20 August 2006, aged 93.

Her connections to the Fortean Society and Forteanism were mostly adulatory. After the Supreme Court ruled in her favor, Forteans “overwhelmingly”—according to Thayer—voted her the Annual Named Fellow. Thayer announced that she had accepted the honor in Doubt 21 (June 1948), noting that he had liked her fight even before the Supreme Court vindicated her stance. He returned to the subject two issues later (December 1948) hoping that McCollum would take the fight in Fortean directions—“We welcome her heartily, and trust that she will be as alert to prevent science from warping the mind of her son as she was to frustrate the Church’s effort.”

As far as I know, that was never McCollum’s cause, though. Indeed, I am not sure that she knew anything about Fort or Forteanism. She did come to know Edwin Wilson, who investigated the Society a bit, and so may have picked up some information from him, but Forteanism never seems to have been a driving force in her work. Rather, she was rooted in the secular and forethought traditions of America, which brought her parallel with Forteanism, but the two never really overlapped. In 1953, the Society offered her book for sale, at three dollars. That was the last mention of McCollum by Thayer.

***********************************

James Burnham

James Burnham The connections between the Society and James Burnham are even more slight—and positive only by implication.

Born 22 November 1905 in Chicago, Burnham was raised Catholic but rejected it for atheism. He graduated from Princeton, attended Oxford, and became a professor of philosophy at New York University. In the 1930s, Burnham helped to organize the American Workers Party, which later merged with a communist party to become the U.S. Workers Party. In the internecine warfare between various leftist groups, Burnham took the side of the Trotskyists. But in 1940, he broke even with this group, starting a short trudge to the right side of the political aisle. He rejected dialectical materialism for a unified science. In time, he rejected Marxism tout court. During World War II, he worked for the OSS, and afterwards became associated with William Buckley’s National Review. He opposed the New Deal, and saw it had elective affinities with other forms of managerialism—fascism and communism.

Late in his life, Burnham returned to the Catholicism of his youth. He died 28 July 1987, aged 81.

The only connection between Burnham and the Fortean Society is a single mention in Doubt 23 (December 1948). After castigating Ben Hecht for taking the side of Israeli terrorists over the British army but refusing to throw him out of the Society—Thayer was in a hard spot, respecting Hecht, but also attacked by Russell, who hated Hecht’s stance—Thayer went on to list other members that the Society now repudiated. Among them was Burnham. The renunciation raises more questions than it answers.

Clearly at some point Thayer thought Burnham worthy of respect and must have invited him to join the Society. (Presumably, he accepted.) But when that was is unclear. Perhaps in the early 1940s, when Burnham was moving away from communism and rejecting all forms of state management. (He published “The Managerial Revolution” in 1941. His 1943 book “The Machiavellians,” which also warned against centralized government control, may also have appealed to Thayer.) There is no record, but this timeline makes some sense. What Burnham did to warrant public shaming, though, is not clear. Perhaps it was his 1947 book “The Struggle for the World,” which urged the U.S. to take a belligerent stance toward the Soviet Union and communism.

Whatever the case, he was an icon of Forteanism for at least a brief moment, then dropped. That he had any other connections to Fort seems doubtful in light of his search for a true science of politics. It is not that he was on either the right or the left—the Fortean Society had members from both sides—but that his philosophy was so opposed to the humorous, skeptical ideas of Fort and, later, the extreme pacifism of Thayer, and his sense that calling people communists was nothing more than a rhetorical move to define someone outside the realm of reasonable discourse and make them vulnerable to any kind of attack.

Born 22 November 1905 in Chicago, Burnham was raised Catholic but rejected it for atheism. He graduated from Princeton, attended Oxford, and became a professor of philosophy at New York University. In the 1930s, Burnham helped to organize the American Workers Party, which later merged with a communist party to become the U.S. Workers Party. In the internecine warfare between various leftist groups, Burnham took the side of the Trotskyists. But in 1940, he broke even with this group, starting a short trudge to the right side of the political aisle. He rejected dialectical materialism for a unified science. In time, he rejected Marxism tout court. During World War II, he worked for the OSS, and afterwards became associated with William Buckley’s National Review. He opposed the New Deal, and saw it had elective affinities with other forms of managerialism—fascism and communism.

Late in his life, Burnham returned to the Catholicism of his youth. He died 28 July 1987, aged 81.

The only connection between Burnham and the Fortean Society is a single mention in Doubt 23 (December 1948). After castigating Ben Hecht for taking the side of Israeli terrorists over the British army but refusing to throw him out of the Society—Thayer was in a hard spot, respecting Hecht, but also attacked by Russell, who hated Hecht’s stance—Thayer went on to list other members that the Society now repudiated. Among them was Burnham. The renunciation raises more questions than it answers.

Clearly at some point Thayer thought Burnham worthy of respect and must have invited him to join the Society. (Presumably, he accepted.) But when that was is unclear. Perhaps in the early 1940s, when Burnham was moving away from communism and rejecting all forms of state management. (He published “The Managerial Revolution” in 1941. His 1943 book “The Machiavellians,” which also warned against centralized government control, may also have appealed to Thayer.) There is no record, but this timeline makes some sense. What Burnham did to warrant public shaming, though, is not clear. Perhaps it was his 1947 book “The Struggle for the World,” which urged the U.S. to take a belligerent stance toward the Soviet Union and communism.

Whatever the case, he was an icon of Forteanism for at least a brief moment, then dropped. That he had any other connections to Fort seems doubtful in light of his search for a true science of politics. It is not that he was on either the right or the left—the Fortean Society had members from both sides—but that his philosophy was so opposed to the humorous, skeptical ideas of Fort and, later, the extreme pacifism of Thayer, and his sense that calling people communists was nothing more than a rhetorical move to define someone outside the realm of reasonable discourse and make them vulnerable to any kind of attack.

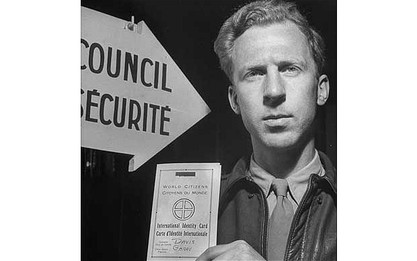

Garry Davis

Garry Davis Garry Davis was the most Fortean of the Fortean icons: there was a reciprocal relationship absent in the cases of McCollum and Burnham.

Sol Gareth Davis was born 27 July 1921 in Bar Harbor, Maine. He graduated from the Episcopal Academy and later Carnegie Institute of Technology. Davis served in World War II and was so horrified by what he saw—and did—that in 1948, while in Paris, he gave up his American citizenship to become a “citizen of the world.” In France, he became attached to Albert Camus, André Gide, and others, becoming a voice for a single world government. Through the 1940s and 1950s, he continued to press these ideas, expanding them.

Garry Davis died 24 July 2013, aged 91.

Unlike McCollum and Burnham, Davis had an independent acquaintance with Fort. He read the serialized version of “Lo!” that appeared in Astounding in 1934. (The Golden Age of science fiction is 12.) Apparently, he was a big fan of “Astounding.” He came to the attention of the Fortean Society in the wake of his renouncing his citizenship and the story he caused in France and at U.N. meeting there. Russell was impressed and suggest that Thayer approach him. Immediately after McCollum was named an annual fellow, there was, according to Thayer, a slew of nominations for Davis. Initially, he was unsure.

In 1950, Thayer hosted a dinner for Davis in New York. Thayer reported in Doubt 29 (July 1950):

“The question mark which was placed after the name of Accepted Fellow (19 FS) Garry Davis, when he accepted with his fingers crossed, was removed May 2, 20 FS. A group of New York City Forteans, which included three Founders, and more than a dozen of the pacifically-inclined, together with several of their wives, welcomed Garry at an informal dinner (without speeches) on that date, and YS was left with the impression of fine understanding and sincere respect exchanged by all hands.

“Garry and his bride, Audrey Peters, are both Forteans, born, and the Society can rely upon them to carry that viewpoint with them wherever they go.

“We were particularly lucky to catch Scott Nearing between debates in Philadelphia and Brooklyn, at the end of the Vermont sugaring season. As a veteran campaigner for rational human relationships, and one who has solved the personal problem of living in self-respect under a shamefully organized economic system, Scott made available his life-time of experience toward the promotion of the ‘world-citizen’ concept.

“Pamphleteers Jay J. M. Scandrett and Paul Bleek, endocrinologist Harry Benjamin, M.D., actor Fred Keating, editor and ‘contemporary-archeologist’ Jack Campbell, Founder Sussman, MFS [Frank] McMahon--AND the ladies--all contributed mightily to the discussions which ranged from vegetarianism to Venus with stopovers at Aristophanes’ Lysistrata. Renaissance banking, Einstein and ‘leadership’ cum demagoguery. The press was not invited.

“Garry Davis is in.”

In private, Thayer was not so positive. He called him “sincere,” in a letter to Ezra Pound, which was not necessarily a compliment. He told Russell that, after putting Davis and Scott Nearing into contact with one another “the world will be saved. You and I will be damned.” The cynicism that bonded Thayer and Russell rubbed raw against the optimism of Nearing and Davis—it was uncomfortable for Thayer, even diminishing. In another letter to Russell he said, “Garry Davis is a good boy. I know he must be because I can’t follow his thinking processes. He comes up with logic that must be from heaven since it bears no similarity to anything I ever think about. That’s why it’s effective. That’s why he belongs in. It won’t hurt us old goats to associate with a bona fide lamb.” Which was a way of denigrating Davis’s optimism even while admitting it might have more lasting power.

The following year, there was some desultory correspondence between Russell and Davis—desultory not from lack of enthusiasm, but follow through on Davis’s part. He was very busy. The first letter came from Davis a year after the dinner in New York, Davis telling Russell he was “profoundly affected” by his short story “. . . And Then There Were None.” Davis hoped to meet Russell, but in the time between writing his letter and sending it, he talked with the editor of Astounding, John W. Campbell, and found that Russell was in England, but he still hoped to continue correspondence. (all of which says that Davis was still a science fiction fan.)

Russell’s story told of a planet of earth refugees who call themselves “Gands” after Gandhi. They are anarchic and peaceful, refusing to do anything that they do not want to do. When other earthlings visit to entice them to join the Terran Alliance, the Gands refuse and say that every last one of them will die before they agree. The earthlings leave when they realize that they cannot win over the Gands and some of their numbers seem to be defecting to this new utopia.

Russell sent a response dated 19 June, but Davis did not get around to answering for almost another month, 14 July 1951. Apparently, Russell had remarked on current Indian politics, which Davis used as a jumping-off point. He had just read the book “India Afire,” which proposed that a merging of American supplies and Gandhi democratic socialism could set the stage for the coming of a one-world government—which he linked to Russell’s story, though that story was rooted in anarchism as opposed to what Burnham would have called managerialism. Davis also liked Russell’s evocation of Nehru, whom he saw as representing the necessary human individuals who desire to make a change in the world.

The later then swerved, highlighting some connections Davis had to Fort, but distancing him from the individuality honored by Russell and Thayer. Davis wrote about how all of human life is a single organism, with people as cells. (Echoes of “Radical Corpuscle.”) What, then, Davis asked, constituted the brain? These are the people influenced by a hope to save the whole thing—people like Nehru and himself (and Russell, he was sure), people who were working to evolve the entire species.

That letter was not sent when it was dated, though. Rather, Davis came back to it on 24 September 1951. He had put the letter in a book he was reading, as a way to remember to send it, but then set the book aside. As he read the letter at this later date, he wasn’t sure he was making any kind of sense. But he sent it any way. Apparently, he was trying to work up an article on the topic, and hoped to send that to Russell for criticism. He then asked about more mundane matters. Was there any science fiction on British TV? Davis watched the shows on American television, and even hoped to become a director or producer for television, making science fiction shows of his own.

That was the last letter between Russell and Davis and, as far as I know, the last link between Davis and Forteanism. Unlike Burnham, he shared a political vision with the Forteans—not an exact one, but with overlapping points. And unlike McCollum that vision had been influenced by Fort, not drawn up in parallel. Like Fort, he was a monist. Like Thayer and Russell, anti-war.

But then, he was off on other matters, leaving the Fortean Society (and Fort) behind. Thayer never mentioned him in Doubt again.

Sol Gareth Davis was born 27 July 1921 in Bar Harbor, Maine. He graduated from the Episcopal Academy and later Carnegie Institute of Technology. Davis served in World War II and was so horrified by what he saw—and did—that in 1948, while in Paris, he gave up his American citizenship to become a “citizen of the world.” In France, he became attached to Albert Camus, André Gide, and others, becoming a voice for a single world government. Through the 1940s and 1950s, he continued to press these ideas, expanding them.

Garry Davis died 24 July 2013, aged 91.

Unlike McCollum and Burnham, Davis had an independent acquaintance with Fort. He read the serialized version of “Lo!” that appeared in Astounding in 1934. (The Golden Age of science fiction is 12.) Apparently, he was a big fan of “Astounding.” He came to the attention of the Fortean Society in the wake of his renouncing his citizenship and the story he caused in France and at U.N. meeting there. Russell was impressed and suggest that Thayer approach him. Immediately after McCollum was named an annual fellow, there was, according to Thayer, a slew of nominations for Davis. Initially, he was unsure.

In 1950, Thayer hosted a dinner for Davis in New York. Thayer reported in Doubt 29 (July 1950):

“The question mark which was placed after the name of Accepted Fellow (19 FS) Garry Davis, when he accepted with his fingers crossed, was removed May 2, 20 FS. A group of New York City Forteans, which included three Founders, and more than a dozen of the pacifically-inclined, together with several of their wives, welcomed Garry at an informal dinner (without speeches) on that date, and YS was left with the impression of fine understanding and sincere respect exchanged by all hands.

“Garry and his bride, Audrey Peters, are both Forteans, born, and the Society can rely upon them to carry that viewpoint with them wherever they go.

“We were particularly lucky to catch Scott Nearing between debates in Philadelphia and Brooklyn, at the end of the Vermont sugaring season. As a veteran campaigner for rational human relationships, and one who has solved the personal problem of living in self-respect under a shamefully organized economic system, Scott made available his life-time of experience toward the promotion of the ‘world-citizen’ concept.

“Pamphleteers Jay J. M. Scandrett and Paul Bleek, endocrinologist Harry Benjamin, M.D., actor Fred Keating, editor and ‘contemporary-archeologist’ Jack Campbell, Founder Sussman, MFS [Frank] McMahon--AND the ladies--all contributed mightily to the discussions which ranged from vegetarianism to Venus with stopovers at Aristophanes’ Lysistrata. Renaissance banking, Einstein and ‘leadership’ cum demagoguery. The press was not invited.

“Garry Davis is in.”

In private, Thayer was not so positive. He called him “sincere,” in a letter to Ezra Pound, which was not necessarily a compliment. He told Russell that, after putting Davis and Scott Nearing into contact with one another “the world will be saved. You and I will be damned.” The cynicism that bonded Thayer and Russell rubbed raw against the optimism of Nearing and Davis—it was uncomfortable for Thayer, even diminishing. In another letter to Russell he said, “Garry Davis is a good boy. I know he must be because I can’t follow his thinking processes. He comes up with logic that must be from heaven since it bears no similarity to anything I ever think about. That’s why it’s effective. That’s why he belongs in. It won’t hurt us old goats to associate with a bona fide lamb.” Which was a way of denigrating Davis’s optimism even while admitting it might have more lasting power.

The following year, there was some desultory correspondence between Russell and Davis—desultory not from lack of enthusiasm, but follow through on Davis’s part. He was very busy. The first letter came from Davis a year after the dinner in New York, Davis telling Russell he was “profoundly affected” by his short story “. . . And Then There Were None.” Davis hoped to meet Russell, but in the time between writing his letter and sending it, he talked with the editor of Astounding, John W. Campbell, and found that Russell was in England, but he still hoped to continue correspondence. (all of which says that Davis was still a science fiction fan.)

Russell’s story told of a planet of earth refugees who call themselves “Gands” after Gandhi. They are anarchic and peaceful, refusing to do anything that they do not want to do. When other earthlings visit to entice them to join the Terran Alliance, the Gands refuse and say that every last one of them will die before they agree. The earthlings leave when they realize that they cannot win over the Gands and some of their numbers seem to be defecting to this new utopia.

Russell sent a response dated 19 June, but Davis did not get around to answering for almost another month, 14 July 1951. Apparently, Russell had remarked on current Indian politics, which Davis used as a jumping-off point. He had just read the book “India Afire,” which proposed that a merging of American supplies and Gandhi democratic socialism could set the stage for the coming of a one-world government—which he linked to Russell’s story, though that story was rooted in anarchism as opposed to what Burnham would have called managerialism. Davis also liked Russell’s evocation of Nehru, whom he saw as representing the necessary human individuals who desire to make a change in the world.

The later then swerved, highlighting some connections Davis had to Fort, but distancing him from the individuality honored by Russell and Thayer. Davis wrote about how all of human life is a single organism, with people as cells. (Echoes of “Radical Corpuscle.”) What, then, Davis asked, constituted the brain? These are the people influenced by a hope to save the whole thing—people like Nehru and himself (and Russell, he was sure), people who were working to evolve the entire species.

That letter was not sent when it was dated, though. Rather, Davis came back to it on 24 September 1951. He had put the letter in a book he was reading, as a way to remember to send it, but then set the book aside. As he read the letter at this later date, he wasn’t sure he was making any kind of sense. But he sent it any way. Apparently, he was trying to work up an article on the topic, and hoped to send that to Russell for criticism. He then asked about more mundane matters. Was there any science fiction on British TV? Davis watched the shows on American television, and even hoped to become a director or producer for television, making science fiction shows of his own.

That was the last letter between Russell and Davis and, as far as I know, the last link between Davis and Forteanism. Unlike Burnham, he shared a political vision with the Forteans—not an exact one, but with overlapping points. And unlike McCollum that vision had been influenced by Fort, not drawn up in parallel. Like Fort, he was a monist. Like Thayer and Russell, anti-war.

But then, he was off on other matters, leaving the Fortean Society (and Fort) behind. Thayer never mentioned him in Doubt again.