So what did Lamantia mean when he wrote that he had died in 1945? Certainly, part of it may have been his break with surrealism. He had invested a lot of himself into the movement, had defined himself as a revolutionary—both socialist and surrealist—and seeing this movement flounder would have been difficult. But he did not act like a dead man: he continued to study and investigate other forms of cultural radicalism.

More likely to have “killed” him is the weapon most closely associated with that year, 1945: the atomic bomb. We can see evidence for this claim in his letters to the selective service board petitioning for conscientious objector status. He argued that the nineteenth-century dream of perfecting man through science had reached its inevitable conclusion in the atomic bomb, and that conclusion was tragic. The state, he said, was evil. Lamantia rooted his understanding of humankind’s predicament in a religious vision. God, he said, was reality—was nature. But through consciousness humans had separated themselves from nature, from the whole. Another autobiographical note, dated the end of August 1961, makes the connection more explicit. The apocalypse had already come, he said, and so humans needed to find a new way of life, “Anything not identifiable with the stupid, synthetic half/life of postAtomicBomb man, his exploded his cities, literature, art, his corny mis/education, his phantom governments, his corny reasoning, sick politics . . .”

Despite his death, Lamantia continued to study poetry. [Now that’s a Fortean sentence!] At the University of California, Berkeley—which he attended but never graduated—he took classes from Josephine Miles, the doyenne of Bay Area poetry; although her work tended toward the more mainstream, she encouraged students such as Robert Duncan to explore and foment what would become the Berkeley Renaissance. Lamantia also became closely attached to Kenneth Rexroth, whose encyclopedic knowledge of poetry proved an education in itself. Rexroth influenced Lamantia to turn his poetic attention to nature, one of Rexroth’s common themes. Lamantia also seemed to have been influenced by Rexroth’s anarchic politics. In December 1960 he wrote a brief manifesto on the “anarchist state” saying that the goal of the state should be to nurture individual genius. He destroyed a great deal of poems he wrote during this period, though, an act referenced in a later collection, Destroyed Works.

Much of his time during the years after World War II were spent in search of meaning. Given his interpretation of humankind’s place in the universal order and the destruction wrought by Western thought and science, it is no wonder that Lamantia explored other forms of culture during this period. Yet a third autobiographical note from the early 1960s notes that at this time he developed an interest in Jazz and “negro culture.” He experimented with marijuana. At the University, he studied “Asian subjects, Vedanta, Buddhism, Chinese religion and philosophy” (which he had derided to Leite from New York). Lamantia then went “underground,” as he called it, and traveled the world—searching, it seems, for mystical experiences. He tried peyote with Native Americans in Nevada and Mexico, went to North Africa and France before returning the States.

Allen Ginsburg memorialized one of Lamantia’s mystical experiences in “Howl”:

I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by

madness, starving hysterical naked,

dragging themselves through the negro streets at dawn

looking for an angry fix,

angelheaded hipsters burning for the ancient heavenly

connection to the starry dynamo in the machin-

ery of night,

who poverty and tatters and hollow-eyed and high sat

up smoking in the supernatural darkness of

cold-water flats floating across the tops of cities

contemplating jazz,

who bared their brains to Heaven under the El and

saw Mohammedan angels staggering on tene-

ment roofs illuminated

The last line refers to an event in 1953. On Post Street in San Francisco, Lamantia, while reading the Koran, felt himself leave his body and enter a state of perfect blissfulness. For a time, he considered becoming a Muslim, but, instead, the following year converted to Catholicism. Of course, Lamantia, the son of Italian immigrants, had already been baptized, but his family was never particularly observant. Through 1955, he continued to struggle with what he latter called “a crisis of conversion.”

That year, 1955, on October 7, at the “Six Poets at Gallery Six” event the Beat Generation was born—if that doesn’t put too fine a point on it. Kenneth Rexroth introduced Allen Ginsberg, Philip Lamantia, Michael McClure, Philip Whalen, Gary Snider. Jack Kerouac was in the audience and later wrote about the night. Ginsberg debuted “Howl”—a poem that owed a great deal to Lamantia’s automatic writing and free associations. Lamantia himself read first: but he read known of his own poems, choosing, instead, poems written by John Hoffman, whom he had met in 1947 and who died mysteriously in Mexico in 1952. Hoffman had been a great friend and another religious seeker.

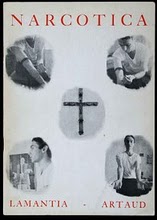

Lamantia’s choice to not read his own poems seems a reflection of his crisis of conversion. In a later interview, he said that Rexroth tried to convince him that his poems were not a mortal sin, but it was in vain. Lamantia had put together a book of poems, which was supposed to have been published by Bern Porter that year, but Tau would not be published until after Lamantia’s death. Lamantia did not have another collection published until 1959, when Ekstasis appeared. These poems were much clearly influenced by Christian mysticism. Despite this conversion, he continued to use narcotics—and demand their legalization—into the 1960s.

After his resurrection—or conversion—Lamantia published much more often—seven books between 1959 and 1970, including a selection of previously published works.

Eventually, though, he found himself returning to surrealism and breaking from the Church (which he then rejoined in the late 1990s). He characterized his later work in an undated autobiographical note:

“Poetic origins lie in surrealism . . . though I have since gone beyond any ‘orthodox’ interpretation of the surrealist position, I retain, the main objective . . . which, today, means an awareness of the most hidden levels of sensibility, vision & being”

“I believe in a poetry that conveys the poetic state, the poetic trance; hence I recognize as primary writing which bears in its marrow the poet’s striving into the ‘essentials’ of Being—in which the Eye has beheld & recorded & allowed to be transformed what lies beyond the narrow confines of pre-conceptions, cerebration or merely literary pre-conditioning.”

Despite his death, Lamantia continued to study poetry. [Now that’s a Fortean sentence!] At the University of California, Berkeley—which he attended but never graduated—he took classes from Josephine Miles, the doyenne of Bay Area poetry; although her work tended toward the more mainstream, she encouraged students such as Robert Duncan to explore and foment what would become the Berkeley Renaissance. Lamantia also became closely attached to Kenneth Rexroth, whose encyclopedic knowledge of poetry proved an education in itself. Rexroth influenced Lamantia to turn his poetic attention to nature, one of Rexroth’s common themes. Lamantia also seemed to have been influenced by Rexroth’s anarchic politics. In December 1960 he wrote a brief manifesto on the “anarchist state” saying that the goal of the state should be to nurture individual genius. He destroyed a great deal of poems he wrote during this period, though, an act referenced in a later collection, Destroyed Works.

Much of his time during the years after World War II were spent in search of meaning. Given his interpretation of humankind’s place in the universal order and the destruction wrought by Western thought and science, it is no wonder that Lamantia explored other forms of culture during this period. Yet a third autobiographical note from the early 1960s notes that at this time he developed an interest in Jazz and “negro culture.” He experimented with marijuana. At the University, he studied “Asian subjects, Vedanta, Buddhism, Chinese religion and philosophy” (which he had derided to Leite from New York). Lamantia then went “underground,” as he called it, and traveled the world—searching, it seems, for mystical experiences. He tried peyote with Native Americans in Nevada and Mexico, went to North Africa and France before returning the States.

Allen Ginsburg memorialized one of Lamantia’s mystical experiences in “Howl”:

I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by

madness, starving hysterical naked,

dragging themselves through the negro streets at dawn

looking for an angry fix,

angelheaded hipsters burning for the ancient heavenly

connection to the starry dynamo in the machin-

ery of night,

who poverty and tatters and hollow-eyed and high sat

up smoking in the supernatural darkness of

cold-water flats floating across the tops of cities

contemplating jazz,

who bared their brains to Heaven under the El and

saw Mohammedan angels staggering on tene-

ment roofs illuminated

The last line refers to an event in 1953. On Post Street in San Francisco, Lamantia, while reading the Koran, felt himself leave his body and enter a state of perfect blissfulness. For a time, he considered becoming a Muslim, but, instead, the following year converted to Catholicism. Of course, Lamantia, the son of Italian immigrants, had already been baptized, but his family was never particularly observant. Through 1955, he continued to struggle with what he latter called “a crisis of conversion.”

That year, 1955, on October 7, at the “Six Poets at Gallery Six” event the Beat Generation was born—if that doesn’t put too fine a point on it. Kenneth Rexroth introduced Allen Ginsberg, Philip Lamantia, Michael McClure, Philip Whalen, Gary Snider. Jack Kerouac was in the audience and later wrote about the night. Ginsberg debuted “Howl”—a poem that owed a great deal to Lamantia’s automatic writing and free associations. Lamantia himself read first: but he read known of his own poems, choosing, instead, poems written by John Hoffman, whom he had met in 1947 and who died mysteriously in Mexico in 1952. Hoffman had been a great friend and another religious seeker.

Lamantia’s choice to not read his own poems seems a reflection of his crisis of conversion. In a later interview, he said that Rexroth tried to convince him that his poems were not a mortal sin, but it was in vain. Lamantia had put together a book of poems, which was supposed to have been published by Bern Porter that year, but Tau would not be published until after Lamantia’s death. Lamantia did not have another collection published until 1959, when Ekstasis appeared. These poems were much clearly influenced by Christian mysticism. Despite this conversion, he continued to use narcotics—and demand their legalization—into the 1960s.

After his resurrection—or conversion—Lamantia published much more often—seven books between 1959 and 1970, including a selection of previously published works.

Eventually, though, he found himself returning to surrealism and breaking from the Church (which he then rejoined in the late 1990s). He characterized his later work in an undated autobiographical note:

“Poetic origins lie in surrealism . . . though I have since gone beyond any ‘orthodox’ interpretation of the surrealist position, I retain, the main objective . . . which, today, means an awareness of the most hidden levels of sensibility, vision & being”

“I believe in a poetry that conveys the poetic state, the poetic trance; hence I recognize as primary writing which bears in its marrow the poet’s striving into the ‘essentials’ of Being—in which the Eye has beheld & recorded & allowed to be transformed what lies beyond the narrow confines of pre-conceptions, cerebration or merely literary pre-conditioning.”