Kathleen Ludwick had a lucrative 1930, about that we can be reasonably sure. About anything else—not much. Although she did leave evidence she appreciated her Fort.

Ludwick had come to the attention of bibliographers before I happened upon her, for her story in Amazing Stories Quarterly “Dr. Immortelle” (1930, of course). In his great resource Science Fiction: The Gernsback Years, Everett Bleiler supposes that the Kathleen Ludwick listed as writing the article might be the same Kathleen Ludwick who the social security agency listed as dying in 1970. That Kathleen Ludwick was born in New York in 1892, and passed in Maryland.

Ludwick had come to the attention of bibliographers before I happened upon her, for her story in Amazing Stories Quarterly “Dr. Immortelle” (1930, of course). In his great resource Science Fiction: The Gernsback Years, Everett Bleiler supposes that the Kathleen Ludwick listed as writing the article might be the same Kathleen Ludwick who the social security agency listed as dying in 1970. That Kathleen Ludwick was born in New York in 1892, and passed in Maryland.

It is doubtful that this is the Kathleen Ludwick we are after.

Why? Because the Kathleen Ludwick who wrote “Dr. Immortelle” gave her address as Oakland California. And, from the census of that most productive of years, it is known that there was a (different) Kathleen Ludwick in Oakland. That Ludwick says that she was sixty—so born around 1870—and originally from Nevada.

There is further reason to suspect that there were two Kathleen Ludwicks living around this time. A search of the name at newspaperarchives.com gives a pot of articles from Pennsylvania and a second lot from Oakland.

Furthermore, the Kathleen Ludwick living in Oakland for the 1930 census gives her occupation as writer.

So, then, stipulate that the Kathleen Ludwick of the 1930 census is the Kathleen Ludwick of interest. Furthermore, stipulate that the Kathleen Ludwick of the census is the same one who wrote several letters to the Oakland Tribune, among other things arguing for a new library and protesting the conversion of University High School into a home for veterans. If this is right, then the letters further confirm her identity, as the writer claims to have both a son who was a veteran and a grandson. A woman born in 1892 would have only been (about) 54 when she made this claim in 1946. This is fairly young to have a grandson who served in WWII, although not impossible. A woman born in 1870 would have been 76, which makes more sense.

This is the Kathleen Ludwick in question then, born in Nevada in 1870. What else can we say about her?

Not much.

Letters to the editor begin to appear in 1937. They last until 1947.

California has no death records for anyone by the name Kathleen Ludwick. Ancestry.com has no records for Kathleen Ludwick before 1930. The census notes that she was divorced, and so maybe lived under a different surname. But searches for her using various other facts of her life—first name only, birth state, birth year(s)—turns up no obvious candidates. That doesn’t mean she didn’t exist, or that Kathleen Ludwick was a fake name—although that is possible—it just means there is no way to definitively identify her. The lack of death records is especially a hindrance—and another question mark about her.

It is possible to identify some of her writing, though. Bleiler noted that, in addition to her tale for Amazing Stories Quarterly, she contributed to Western Story. And, indeed, bibliographers have found stories by Ludwick in that magazine.

All but two were published in 1930. The other two come from 1929 and 1931:

What the Western Red Man Ate: Apaws, (article) Western Story Magazine Dec 28 1929

What the Western Red Man Ate: Fruit (ar) Western Story Magazine Jan 4 1930

The Humanness of the Indian: Different Viewpoints (ar) Western Story Magazine May 17 1930

The Humanness of the Indian: Social and Family Relations (column) Western Story Magazine May 24 1930

What the Western Red Man Ate (ar) Western Story Magazine Jun 14 1930

The Humanness of the Indian: Gratitude (cl) Western Story Magazine Jun 21 1930

The Humanness of the Indian: Were the Indians Lazy? (cl) Western Story Magazine Jul 5 1930

What the Western Red Man Ate: Wokas, the Yellow Water Lily (ar) Western Story Magazine Aug 2 1930

The Humanness of the Indian: Religion, Burial Customs, etc. (ar) Western Story Magazine Aug 30 1930

When Rattlers Bite (ar) Western Story Magazine Oct 11 1930

Poisonous Snakes (ar) Western Story Magazine Dec 6 1930

Hypnotic Snakes (ar) Western Story Magazine Mar 7 1931

As for speculative fiction, what is known is that she wrote one story:

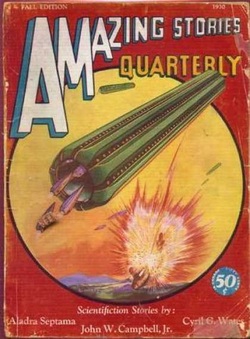

Dr. Immortelle Amazing Stories Quarterly, Fall 1930.

It was republished twice:

Fantastic, May 1968

More Tales of Unknown Horror, (Jan 1979, ed. Peter Haining, publ. New English Library)

Bleiler dismisses this story as “Pretty bad. Involuted and confusing.” It’s also worth noting that the author assumes whites are a superior race—given the titles alone of her pieces for Western Story one suspects that Ludwick may not have had the most progressive racial views. But at this point, such suggestions are highly speculative.

Later science fiction critics, approaching the tale from a decidedly feminist point of view, have not necessarily contradicted this opinion, but added to it. Jane L. Donawerth and Carol A. Kolmerten connect the story to a tradition of fantastic fiction that descends from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Eric Leif Davin puts her in the line of Victorian feminism, which promoted women’s positive qualities and saw them ending war and making the world a better place.

From these accounts, her story owes nothing in particular to Charles Fort. But that she read and admired Fort is not in question.

On 8 July 1947, in light of the nation’s fascination with flying saucers, the Oakland Tribune offered what was really a mealy-mouthed editorial, refusing to take a stand on the issue and not that, of nothing else, it was fun. In the course of covering the subject, the unnamed editorialists noted that Forteans—followers of Charles Fort—were nonplussed by the discussion: they were primed for such stories.

Five days later, the paper ran three letters in response—all by women, interestingly. The first made fun of the phenomenon. The second wanted answers from the government. The third was from Ludwick and focused on Fort: “Well, shiver my timbers! Was I astounded, amazed to read the reference to Charles Fort, the Apostle of Doubt, the High Priest of Skepticism, in the Tribune!,” she began.

Ludwick went on to say that she had independently reached Fort’s conclusion that astronomical objects must be much closer than astronomers declaimed. After all, how could she see a moon that was a quarter of a million miles away? Or a sun 93 million miles away!

It is hard to know whether this was meant as a joke or not: there was no obvious wink and nudge. But the context suggests that, if not a joke, the claim was meant, at least, in the same light-hearted manner Fort made his arguments.

At any rate, she continued on, speculating what the flying saucers might be if, indeed, the heavens were not so far away. Perhaps, she suggested, some enemy nation had sent radio-active material into the sky, but then dismissed the possibility because the enemy nation would be harmed just as well.

Most likely, she concluded, the saucers were an advertising stunt, “like this horrendous monster of the airways that has been seen hovering over Oakland at night advertising some brand of gasoline.” (Possible example.)She wanted such stunts to stop.

The ending was a very clever, and very Fortean twist—undermining the power of the saucers while at the same time subtly suggesting a giant conspiracy, in the vein of Fort’s famous quip, “I think we are property.”

In conjunction with the Tribune’s coverage of flying saucers and David Bascom’s similarly Fortean-themed letter, it is possible to get a sense of how familiar Fort was in Oakland during the late 1940s, and how events of the world made his writing seem especially on point.

Why? Because the Kathleen Ludwick who wrote “Dr. Immortelle” gave her address as Oakland California. And, from the census of that most productive of years, it is known that there was a (different) Kathleen Ludwick in Oakland. That Ludwick says that she was sixty—so born around 1870—and originally from Nevada.

There is further reason to suspect that there were two Kathleen Ludwicks living around this time. A search of the name at newspaperarchives.com gives a pot of articles from Pennsylvania and a second lot from Oakland.

Furthermore, the Kathleen Ludwick living in Oakland for the 1930 census gives her occupation as writer.

So, then, stipulate that the Kathleen Ludwick of the 1930 census is the Kathleen Ludwick of interest. Furthermore, stipulate that the Kathleen Ludwick of the census is the same one who wrote several letters to the Oakland Tribune, among other things arguing for a new library and protesting the conversion of University High School into a home for veterans. If this is right, then the letters further confirm her identity, as the writer claims to have both a son who was a veteran and a grandson. A woman born in 1892 would have only been (about) 54 when she made this claim in 1946. This is fairly young to have a grandson who served in WWII, although not impossible. A woman born in 1870 would have been 76, which makes more sense.

This is the Kathleen Ludwick in question then, born in Nevada in 1870. What else can we say about her?

Not much.

Letters to the editor begin to appear in 1937. They last until 1947.

California has no death records for anyone by the name Kathleen Ludwick. Ancestry.com has no records for Kathleen Ludwick before 1930. The census notes that she was divorced, and so maybe lived under a different surname. But searches for her using various other facts of her life—first name only, birth state, birth year(s)—turns up no obvious candidates. That doesn’t mean she didn’t exist, or that Kathleen Ludwick was a fake name—although that is possible—it just means there is no way to definitively identify her. The lack of death records is especially a hindrance—and another question mark about her.

It is possible to identify some of her writing, though. Bleiler noted that, in addition to her tale for Amazing Stories Quarterly, she contributed to Western Story. And, indeed, bibliographers have found stories by Ludwick in that magazine.

All but two were published in 1930. The other two come from 1929 and 1931:

What the Western Red Man Ate: Apaws, (article) Western Story Magazine Dec 28 1929

What the Western Red Man Ate: Fruit (ar) Western Story Magazine Jan 4 1930

The Humanness of the Indian: Different Viewpoints (ar) Western Story Magazine May 17 1930

The Humanness of the Indian: Social and Family Relations (column) Western Story Magazine May 24 1930

What the Western Red Man Ate (ar) Western Story Magazine Jun 14 1930

The Humanness of the Indian: Gratitude (cl) Western Story Magazine Jun 21 1930

The Humanness of the Indian: Were the Indians Lazy? (cl) Western Story Magazine Jul 5 1930

What the Western Red Man Ate: Wokas, the Yellow Water Lily (ar) Western Story Magazine Aug 2 1930

The Humanness of the Indian: Religion, Burial Customs, etc. (ar) Western Story Magazine Aug 30 1930

When Rattlers Bite (ar) Western Story Magazine Oct 11 1930

Poisonous Snakes (ar) Western Story Magazine Dec 6 1930

Hypnotic Snakes (ar) Western Story Magazine Mar 7 1931

As for speculative fiction, what is known is that she wrote one story:

Dr. Immortelle Amazing Stories Quarterly, Fall 1930.

It was republished twice:

Fantastic, May 1968

More Tales of Unknown Horror, (Jan 1979, ed. Peter Haining, publ. New English Library)

Bleiler dismisses this story as “Pretty bad. Involuted and confusing.” It’s also worth noting that the author assumes whites are a superior race—given the titles alone of her pieces for Western Story one suspects that Ludwick may not have had the most progressive racial views. But at this point, such suggestions are highly speculative.

Later science fiction critics, approaching the tale from a decidedly feminist point of view, have not necessarily contradicted this opinion, but added to it. Jane L. Donawerth and Carol A. Kolmerten connect the story to a tradition of fantastic fiction that descends from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Eric Leif Davin puts her in the line of Victorian feminism, which promoted women’s positive qualities and saw them ending war and making the world a better place.

From these accounts, her story owes nothing in particular to Charles Fort. But that she read and admired Fort is not in question.

On 8 July 1947, in light of the nation’s fascination with flying saucers, the Oakland Tribune offered what was really a mealy-mouthed editorial, refusing to take a stand on the issue and not that, of nothing else, it was fun. In the course of covering the subject, the unnamed editorialists noted that Forteans—followers of Charles Fort—were nonplussed by the discussion: they were primed for such stories.

Five days later, the paper ran three letters in response—all by women, interestingly. The first made fun of the phenomenon. The second wanted answers from the government. The third was from Ludwick and focused on Fort: “Well, shiver my timbers! Was I astounded, amazed to read the reference to Charles Fort, the Apostle of Doubt, the High Priest of Skepticism, in the Tribune!,” she began.

Ludwick went on to say that she had independently reached Fort’s conclusion that astronomical objects must be much closer than astronomers declaimed. After all, how could she see a moon that was a quarter of a million miles away? Or a sun 93 million miles away!

It is hard to know whether this was meant as a joke or not: there was no obvious wink and nudge. But the context suggests that, if not a joke, the claim was meant, at least, in the same light-hearted manner Fort made his arguments.

At any rate, she continued on, speculating what the flying saucers might be if, indeed, the heavens were not so far away. Perhaps, she suggested, some enemy nation had sent radio-active material into the sky, but then dismissed the possibility because the enemy nation would be harmed just as well.

Most likely, she concluded, the saucers were an advertising stunt, “like this horrendous monster of the airways that has been seen hovering over Oakland at night advertising some brand of gasoline.” (Possible example.)She wanted such stunts to stop.

The ending was a very clever, and very Fortean twist—undermining the power of the saucers while at the same time subtly suggesting a giant conspiracy, in the vein of Fort’s famous quip, “I think we are property.”

In conjunction with the Tribune’s coverage of flying saucers and David Bascom’s similarly Fortean-themed letter, it is possible to get a sense of how familiar Fort was in Oakland during the late 1940s, and how events of the world made his writing seem especially on point.