According to Miriam Allen de Ford, Jackson reviewed Fort’s Wild Talents, which came out in June 1932—a month or so after Fort’s death. De Ford mentions the review in her biography of Fort written for Boucher’s Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction; she did not give any bibliographical information, however, and I have been unable to locate it. I looked through the San Francisco Chronicle for June 1932; as well, librarians at the California State Library compiled an index to the Chronicle, and there is no listing for a review of Wild Talents. (There is for Fort’s collected works, though.) It is entirely possible that Jackson published it elsewhere, but I don’t know its location. Assuming it exists, though, that dates Jackson’s awareness of Fort to the early 1930s, just after he joined the Chronicle, at the very least.

What is known is that his interest in Fort became public (again?)—and positive—in the early 1940s, first with the aforementioned review of Fort’s collected works, introduced, edited, and indexed by Tiffany Thayer and published by Henry Holt. Jackson took the opportunity of the publication as an excuse to introduce Fort and his ideas to a wide world, making it clear that he was a Fortean “in spirit” if not “in fact,” as he put it in his “Bookman’s Daily Notebook” on 1 May 1941 (p. 17).

Having now read this article—which is also referenced by de Ford in her biography—it is clear that Jackson’s interpretation of Fort influenced de Ford greatly. Both saw Fort the man as relatively uninteresting—at least they didn’t find much in his biography to note. Like so many others, they were attracted by his ideas. Jackson characterized Fort as “The Man Who Kept Saying ‘No!’” He stood against scientists who made too positive declarations, Jackson thought, and pointed out that there were yet many unexplained things in this world, “hushed up” by scientists because they did not fit into contemporary theories. There’s a certain truth to this, of course, but seeing Fort as only a compiler of the odd ignores his humor and his alternate theories—both of which influenced later thinkers more than the collecting.

Jackson, though, does point to some of these other parts of Fort, comparing him to Rabelais at one point, and noting that while many may not like his writing style—and may therefore dismiss him as sane—others will entertain the teasing thought that perhaps Fort is the only one who is sane, the rest of the world crazy. Those who think so, he says, have “made the first step to becoming a Fortean, because” they have shifted into a new dimension and asked, “What if?” (Not coincidentally, a central question in science fiction.) To those, he recommends Thayer’s Fortean Society which he—at least at this relatively early date—saw as having “no ax to grind” and “no other purpose” than making people reconsider received opinions.

Jackson had reason to return to Fort the following year. He was editing and introducing a collection of Ambrose Bierce’s short stories called Tales of Soldiers and Civilians. The book came out in 1943, but the introduction suggests that it was written in 1942.

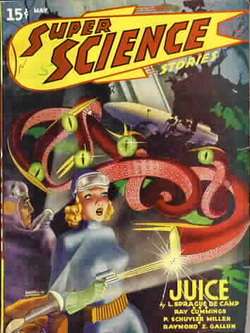

Jackson begins the introduction by considering Bierce’s mysterious end: on 26 December 1913 he crossed into Mexico and was never seen from again. This disappearance, Jackson notes, had become more famous than Bierce’s writings, with plenty of people speculating on the writer’s final days. Jackson obliquely references Robert Heinlein’s novella "Lost Legacy" published in 1941, which had Bierce joining the Lemurians on Mt. Shasta. Jackson suggested Fort’s “mystical” explanation was better. Noting that Bierce disappeared about the same time as someone named Ambrose Small, Fort impishly suggested that perhaps there was an Ambrose collector about. Though only a small comment, the introduction shows a familiarity with Fort and science fiction, and this before it is generally supposed that Jackson and Boucher met. Note that Heinlein’s tale appeared in Super Science Stories, not exactly top-flight science fiction (and was published under the name Lyle Monroe, I believe: see illustration).

We do know that Boucher and Jackson had befriended by the following year--1943—and Fort seemed to be part of that friendship, or least led them in a parallel direction. As mentioned before, Boucher became interested in reports that stones were falling from the sky over Oakland. Jackson, too, had his curiosity piqued and mentioned the stones in his “Bookman’s Daily Notebook” on 1 September 1943. He used the reports as another opportunity to introduce Fort to a public that had not properly attended the writer.

This article evinced a more expansive understanding of Fort, which may reflect Boucher’s influence, Jackson’s development, or his willingness to go further in a second piece. At any rate, Jackson started by describing Fort as a clip collector who wanted to encourage skepticism of science. He mentioned, again, Thayer and the Fortean Society, again lauding them as carrying on Fort’s work, singling out Thayer’s introduction to the collected works as an excellent encapsulation of the Fortean approach to life. (Boucher did not share this enthusiasm for Thayer’s introduction; at least by the 1950s—after Thayer had made many enemies—he compared it to Thayer’s earlier introduction to Lo! And found it lacking that Fortean je ne sais quoi.) Miriam Allen de Ford praised the article in a letter to Boucher and hoped it would gain Fort more readers.

But Jackson did not stop at this conventional—one is tempted to same provincial—interpretation of Fort. He went on to praise Fort’s Rabelaisian exaggerations: “He juggled paradoxes and played games with words—even with sentence structure,” Jackson wrote. “But you’d better read him,” he admonished. “While you’re reading you won’t be sure if you’re on your head or heels. But then Fort knew that. He wrote to shake up the reader. He does.”

There’s an echo of Maynard Shipley’s comment that reading Fort is like riding a comment. But while Shipley is loathe to take any of Fort’s theorizing seriously and spends time defending science against what he sees as Fort’s naiveté, Jackson eschews any such defense of science. Not to put too fine a point on it, but it’s possible to see a transition taking place here, from the Bay Area provincial interpretation of Fort to the looser, more radical understanding championed by Bay Area Forteans in the years after World War II. It is tempting to suggest, as well, that World War II itself mencouraged this new interpretation: the war made it seem that much more likely that humans were, indeed, property; that sinister forces controlled the world; that science would doom us all and that there needed to be not just new facts, but new theories.

Better to take a Fortean approach—to note that possible interpretation, leave it hanging for contemplation, but be ready to dismiss it as only fiction: another story we tell ourselves to make sense of a world that is always beyond our full comprehension.

What is known is that his interest in Fort became public (again?)—and positive—in the early 1940s, first with the aforementioned review of Fort’s collected works, introduced, edited, and indexed by Tiffany Thayer and published by Henry Holt. Jackson took the opportunity of the publication as an excuse to introduce Fort and his ideas to a wide world, making it clear that he was a Fortean “in spirit” if not “in fact,” as he put it in his “Bookman’s Daily Notebook” on 1 May 1941 (p. 17).

Having now read this article—which is also referenced by de Ford in her biography—it is clear that Jackson’s interpretation of Fort influenced de Ford greatly. Both saw Fort the man as relatively uninteresting—at least they didn’t find much in his biography to note. Like so many others, they were attracted by his ideas. Jackson characterized Fort as “The Man Who Kept Saying ‘No!’” He stood against scientists who made too positive declarations, Jackson thought, and pointed out that there were yet many unexplained things in this world, “hushed up” by scientists because they did not fit into contemporary theories. There’s a certain truth to this, of course, but seeing Fort as only a compiler of the odd ignores his humor and his alternate theories—both of which influenced later thinkers more than the collecting.

Jackson, though, does point to some of these other parts of Fort, comparing him to Rabelais at one point, and noting that while many may not like his writing style—and may therefore dismiss him as sane—others will entertain the teasing thought that perhaps Fort is the only one who is sane, the rest of the world crazy. Those who think so, he says, have “made the first step to becoming a Fortean, because” they have shifted into a new dimension and asked, “What if?” (Not coincidentally, a central question in science fiction.) To those, he recommends Thayer’s Fortean Society which he—at least at this relatively early date—saw as having “no ax to grind” and “no other purpose” than making people reconsider received opinions.

Jackson had reason to return to Fort the following year. He was editing and introducing a collection of Ambrose Bierce’s short stories called Tales of Soldiers and Civilians. The book came out in 1943, but the introduction suggests that it was written in 1942.

Jackson begins the introduction by considering Bierce’s mysterious end: on 26 December 1913 he crossed into Mexico and was never seen from again. This disappearance, Jackson notes, had become more famous than Bierce’s writings, with plenty of people speculating on the writer’s final days. Jackson obliquely references Robert Heinlein’s novella "Lost Legacy" published in 1941, which had Bierce joining the Lemurians on Mt. Shasta. Jackson suggested Fort’s “mystical” explanation was better. Noting that Bierce disappeared about the same time as someone named Ambrose Small, Fort impishly suggested that perhaps there was an Ambrose collector about. Though only a small comment, the introduction shows a familiarity with Fort and science fiction, and this before it is generally supposed that Jackson and Boucher met. Note that Heinlein’s tale appeared in Super Science Stories, not exactly top-flight science fiction (and was published under the name Lyle Monroe, I believe: see illustration).

We do know that Boucher and Jackson had befriended by the following year--1943—and Fort seemed to be part of that friendship, or least led them in a parallel direction. As mentioned before, Boucher became interested in reports that stones were falling from the sky over Oakland. Jackson, too, had his curiosity piqued and mentioned the stones in his “Bookman’s Daily Notebook” on 1 September 1943. He used the reports as another opportunity to introduce Fort to a public that had not properly attended the writer.

This article evinced a more expansive understanding of Fort, which may reflect Boucher’s influence, Jackson’s development, or his willingness to go further in a second piece. At any rate, Jackson started by describing Fort as a clip collector who wanted to encourage skepticism of science. He mentioned, again, Thayer and the Fortean Society, again lauding them as carrying on Fort’s work, singling out Thayer’s introduction to the collected works as an excellent encapsulation of the Fortean approach to life. (Boucher did not share this enthusiasm for Thayer’s introduction; at least by the 1950s—after Thayer had made many enemies—he compared it to Thayer’s earlier introduction to Lo! And found it lacking that Fortean je ne sais quoi.) Miriam Allen de Ford praised the article in a letter to Boucher and hoped it would gain Fort more readers.

But Jackson did not stop at this conventional—one is tempted to same provincial—interpretation of Fort. He went on to praise Fort’s Rabelaisian exaggerations: “He juggled paradoxes and played games with words—even with sentence structure,” Jackson wrote. “But you’d better read him,” he admonished. “While you’re reading you won’t be sure if you’re on your head or heels. But then Fort knew that. He wrote to shake up the reader. He does.”

There’s an echo of Maynard Shipley’s comment that reading Fort is like riding a comment. But while Shipley is loathe to take any of Fort’s theorizing seriously and spends time defending science against what he sees as Fort’s naiveté, Jackson eschews any such defense of science. Not to put too fine a point on it, but it’s possible to see a transition taking place here, from the Bay Area provincial interpretation of Fort to the looser, more radical understanding championed by Bay Area Forteans in the years after World War II. It is tempting to suggest, as well, that World War II itself mencouraged this new interpretation: the war made it seem that much more likely that humans were, indeed, property; that sinister forces controlled the world; that science would doom us all and that there needed to be not just new facts, but new theories.

Better to take a Fortean approach—to note that possible interpretation, leave it hanging for contemplation, but be ready to dismiss it as only fiction: another story we tell ourselves to make sense of a world that is always beyond our full comprehension.