David Bascom was born in Pennsylvania in 1912 to Franklin Bascom and Mabel (Rathbun) Bascom. His place of birth is given as Oil City, Pennsylvania; the previous census had given Franklin’s job as stenographer. By 1918, Franklin was in Arizona; by 1920, Franklin and Mabel divorced, with Franklin still in Arizona, where he was a forest ranger, and Mabel in Pennsylvania working as a stenographer: she was forty and supporting a 7 year old son, which could not have been easy, although her parents were nearby.

By 1938, Bascom had relocated to Oakland, California, according to voter registration records. (He was a democrat.) He was working as a commercial artist. There is reason to believe that Bascom had come West earlier than this—perhaps driven by the Depression. A 1965 article about Bascom in Sports Illustrated gives a brief biography, stating that he studied art in San Francisco and worked in the circulation department of the San Francisco Chronicle, only later moving into advertising. His given profession suggests, according to this timeline, that he had already studied art and worked for the newspaper.

An Oakland Tribune article from 1940 puts Bascom in the advertising game, working for Awful Fresh MacFarlane and a member of the Oakland Advertising Club. Awful Fresh MacFarlane was a candy and nut store. An article from the same paper the following year also gives a glimpse of Bascom’s fondness for invention. He had apparently created something called a “steetoscope” that, using fluoroscopy, followed candy through the digestive system.

In 1942, according to the same Sports Illustrated article, he went to work as a copy writer for Garfield & Guild. He had moved by this point, and apparently married, Mary Charlene (Smith). He was also living with his mother. David was still a democrat; his wife and mother were republicans. David called himself an advertising manager, his wife a stenographer. At some point, the Bascoms had a son, and it may have been in the early 1940s, since Peck lists herself as a housewife. As her parents seemed to do for her, she may have been helping her son raise his child.

Billboard magazine noted that Garfield & Guild broke up in either late 1948 or early 1949. Guild joined Bascom to create Guild Bascom & Bonfigli. Over the next decade, the agency became a powerhouse in advertising. In 1957, Bascom was awarded “outstanding achievement in advertising” by the Association of Advertising Men and Women—the first time an advertising man in the West had been so honored. Two years later, the New York Times noted that GB&B was the talk of San Francisco, doing $12 million in billing—all with national accounts. And in 1960, the agency did the advertising for John F. Kennedy’s presidential bid, pulling in over $2 million. In 1967, after being courted by many suitors over a long time, GB&B merged with New York’s Dancer, Fitzgerald, Sample.

Through all of this, Bascom indulged his tinkering and sense of humor. The same New York Times article has it that his office was filled with phones—something on the order of eight—although most did not work; they were a gag. And behind him on the wall were pictures of his ulcers. According to Bascom, it was his ulcers—and Guild—who turned him on to the Zen art of fly-fishing. After reading through some of the literature and taking some trips, Bascom felt confident to try making his own fly. He added feathers, tin, ribbon, Christmas ornaments, yarn. A wretched mess, he called it, and—using his advertising skills—made up a flyer advertising its sale, which he sent to 150 people; he even started selling the fly in a Montana fishing store. This was about the time of his mother's death, in 1961.

The advertisement took off, and soon became a parody magazine—the last bastion of Yellow Journalism, Bascom trumpeted. Articles included such searching inquiries, as “Is Smokey the Bear a Communist Spy?” In the manner of San Francisco collagists, he illustrated the rag with simple line drawings he did himself as well as pictures he cut from magazines and prints—although they were not always relevant to the text.

Bascom was also inspired by another of Guild’s passions, golfing, and invented and patented a golfishing clubrod. It allowed the user to hit the ball with a driver, carrying fishing line so that the cast would go out farther than if thrown; alternatively, if a golfer hit a ball into a water hazard, he (or she) could reel it back onto dry land.

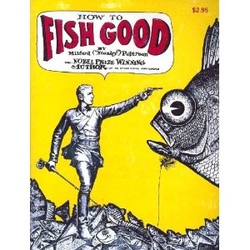

Bascom retired from the agency in the late 1960s or early 1970s, and continued what Tide—an advertising journal—had called his puckish ways. He continued to work on A Wretched Mess, although now under the name Milford Poltroon, and even expanded to sending out calendars. In 1971, under his alter ego, he published How to Fish Good, a parody of fishing books. A sequel appeared in 1977, The Happy Fish Hooker. Under the same name, he published The Phony Phone Book, apparently a collection of humorous ways to answer the phone.

Bascom died in 1985.

Who knows when Bascom had his first run in with Fort or Fortean phenomena? What is known, is that he was involved by 1947. In July of that year, the Oakland Tribune did a large spread on the nation’s fascination with flying saucers, first reported that year in the state of Washington. The stories started on page 1 and continued on page 3. They were no serious—and Bascom was part of the joking. He said he had seen lights in the sky, but they did not look like flying saucers, or plates. Rather, they resembled . . . gravy boats!

In response to a series of letters published in the same paper on the topic of the moon, Bascom was moved to write a letter that was published on 22 May 1948. He expressed mock amazement at the “misinformed writers” who had clearly been exposed to the “completely erroneous information” in science and astronomy texts. Such books, he said, obviously could not be taken seriously: they had it that tomatoes were poisonous, flying machines and submarines were impossible, and kangaroos avoided migraines by eating fresh salmon.

Yeah, those are definitely odd claims.

Rather, Bascom went on, the moon was made of green cheese. In support of this—admittedly scoffed at—contention, Bascom cited Dr. Throckmorton’s work in “Behind the Beyond.” This reference is mysterious. There is a book called Behind the Beyond by Stephen Leacock, which is a nonsense novel, but there is no reference in it to Throckmorton. Maybe that was part of the joke.

At any rate, the other source cited for this claim was—Charles Fort!

Tongue firmly in cheek, Bascom goes on to say that the moon’s craters are made by the nibbling of rats and the air composed of Cheddaroxide, which can be converted into gasses breathable by humans with “a common cheese-gas converter” added to any gas mask. He ends with what had become a common plea—“I say by all means let us establish bases on the moon before some other nation or planet gets the jump on us.”

While a bit broader than Fort’s, the humor was clearly Fortean, using the style of science to arrive at ridiculous conclusions that undermined science’s authority—and its sanctimony, as well as the pretensions of those who took it too seriously.