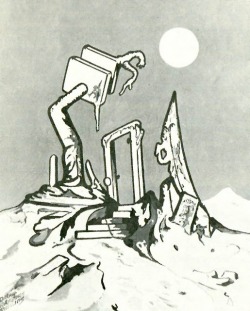

From Destiny 7, Winter 1953.

Ralph Rayburn Phillips did not live in the Bay Area—he was a Portlander. But, he did come to the Bay Area often, and was among those who dropped in on the Fortean meetings, at least according to Don Herron. And so I have included him here, among the Bay Area Forteans. There’s not a lot on Phillips, but it is possible to piece together an outline of his life from census records, a file held at the Portland Art Museum, and a brief biographical sketch in the spring 1953 issue of the fanzine Destiny.

Ralph was born to George T. and May G. on 17 October 1896 in Rutland, Vermont. George T. was a native Vermonter—as were his parents—born just after the end of the Civil War in August 1865. May G. was just a little younger than her husband, born in March 1866 to a couple who had emigrated from Canada. They were married in 1892, when both were in their late twenties.

George’s father had been a farmer and car inspector; May’s had been a carpenter. George became a dentist. The family seemed to start out in good financial standing: by 1900, they owned their home, free and clear.

Ten years later, still in Rutland, Vermont, the house became a bit fuller. According to the census, they took on a boarder from French Canada, and May’s parents, Joseph and Philament Harper were also living with the Phillips. Later evidence also suggests that Ralph had two younger sisters, although they were not captured by the 1910 census. George was the only one working: he was called a “physician.” Ralph was then a student—at “Eastern public schools,” where he studied art.

As he remembered much later, Ralph was a rebel from an early age. He told the Oregon Journal in 1970, “I remember walking out of a Baptist Church in anger. I learned early to hate hopeless conformity.”

By 1920, the family had relocated to Portland, Oregon, without the boarder or May’s parents, who had likely died by this time. According to a brief biography down for a fanzine, the move came when Ralph was eighteen, so about 1914. George now sold farm implements, which seems a step down in prestige, although the family did still own its home.

According to his later recollections, Ralph had continued to study art at high school in Portland, and apprenticed to a commercial artist. The census backs this up, listing his career as commercial artist. (He was still living at home, and so it is likely helped contribute to the family finances.) At some point—maybe in the 1910s, maybe later—he also attended the School of Applied Art in Battle Creek, Michigan.

Sometime in the next ten years, George died, and the family’s fortunes declined. By 1930, they had moved into a rental, and Ralph took a new job—as an organizer and salesman for a fraternal order. The monthly rent was a rather steep $25, but the house had to be big enough to fit Ralph, his mother (who was not working), his sister Iris. Iris had just married a marine engineer, James C. Barrie, but he was at sea when the 1930 census was conducted. Nonetheless, the artistic spirit continued to flow through the family. Iris listed her occupation as poet—a brave choice, indeed!

Ralph would live in Portland until his death in 1974, going from Bohemian to Beatnik to Hippie. The Oregon Journal reported in 1970, “He has been a familiar figure in the SW Park Blocks for years—tall, silver-haired, simply but neatly dressed, and always barefoot. You usually see him on a park bench, sucking on his pipe, as he reads his latest library book, all the while absent-mindedly wriggling his toes.”

During the next decade—if not before—Ralph’s professional world expanded. Probably he received his first real exposure doing Western scenes for the Portland-based magazine “Northwest Background.” At least, he did seem to publish in this magazine, and this work was the most traditional, his later pieces indicating extensive experimentation, which takes time. In the mid-1930s he became intrigued by Buddhism and travelled to Buddhist temples in San Francisco and Los Angeles; for a time he was director of something he called “American Buddhist Society.” Likely this was the American Buddhist Society and Fellowship, founded in 1945 by Robert Ernst Dickhoff, who would later try to link UFOs to Buddhist mythology. (Phillips’s connection to Buddhism seemed to attenuate some over the years: in a 1949 form for the Portland Museum of Art, he made the connection prominent, but he told the Oregon Journal in 1948 he no longer had formal connections to Buddhism.)

Phillips seems to have had a long-standing interest in H.P. Lovecraft and Weird Tales, and this was reflected in his art by the 1940s, when he started to call himself a painter of the “Ultra Weird.” He explained this as “mystic, occult, weird, macabre, psychic-inspired.” He also called his work “modern,” which may have been a nod to the likes of Picasso, although it cut across genres. A few times, at least, he blended his mysticism with his Western scenery, creating images of Native Americans that he thought would interest Spiritualists, who sometimes used Indians as spirit guides.

His methods were occult, too. He tried to get himself into a detached state of mind so that he could receive inspiration from what he called “the invisible world.” He worked at night, when he could see (imagine?) strange faces and alien presences outside his window. Sometimes, the images—and titles—came to him fully formed. His work was often abstract, but—signs of Fort, occasionally had unexpected clarities. He told the Oregon Journal, “I start a picture with no idea what the finished product will be. Often it turns out to be a colorful network of lines, but somewhere in the picture will appear a cat carrying a kitten. Weird, isn’t it?”

The technique and subject matter can sound like a parody of those who uncharitably criticized abstract expressionism—created around the same time that Phillips was working—as something a kid could doodle. But Phillips didn’t see it that way. “Any Tom, Dick, and Harry can paint what he sees, but few can do my type of work.”

Phillips sold paintings to Weird Tales and fanzines; he displayed at science conventions in Los Angeles (1946) and Philadelphia (1947). Robert Bloch, author of Psycho and another devotee of Lovecraft, owned some of his work, as did Erle Korshak, a Chicago science fiction fan who co-founded Shasta Publishing.

How Phillips became involved with the Bay Area Fortean community is unclear. In the late 1940s, he was renting an 8x10 room in a mansion near the corner of SW 12th Avenue and Clay in Portland, where his “favorite friend” was an owl that lived in the eaves. Perhaps he met Haas at a Buddhist temple? Perhaps he met some of the writers at one of the conventions? Perhaps they made contact with him to praise his works. (Haas, after all, was collecting Clark Ashton Smith’s art.) He also developed a fan in Chingwah Lee, an art dealer in San Francisco’s Chinatown and art critic. At any rate, it is known that by the late 1940s he was visiting the San Francisco Bay Area for artistic inspiration, meaning he had connections by then—just as Chapter Two was founded.

Ralph was born to George T. and May G. on 17 October 1896 in Rutland, Vermont. George T. was a native Vermonter—as were his parents—born just after the end of the Civil War in August 1865. May G. was just a little younger than her husband, born in March 1866 to a couple who had emigrated from Canada. They were married in 1892, when both were in their late twenties.

George’s father had been a farmer and car inspector; May’s had been a carpenter. George became a dentist. The family seemed to start out in good financial standing: by 1900, they owned their home, free and clear.

Ten years later, still in Rutland, Vermont, the house became a bit fuller. According to the census, they took on a boarder from French Canada, and May’s parents, Joseph and Philament Harper were also living with the Phillips. Later evidence also suggests that Ralph had two younger sisters, although they were not captured by the 1910 census. George was the only one working: he was called a “physician.” Ralph was then a student—at “Eastern public schools,” where he studied art.

As he remembered much later, Ralph was a rebel from an early age. He told the Oregon Journal in 1970, “I remember walking out of a Baptist Church in anger. I learned early to hate hopeless conformity.”

By 1920, the family had relocated to Portland, Oregon, without the boarder or May’s parents, who had likely died by this time. According to a brief biography down for a fanzine, the move came when Ralph was eighteen, so about 1914. George now sold farm implements, which seems a step down in prestige, although the family did still own its home.

According to his later recollections, Ralph had continued to study art at high school in Portland, and apprenticed to a commercial artist. The census backs this up, listing his career as commercial artist. (He was still living at home, and so it is likely helped contribute to the family finances.) At some point—maybe in the 1910s, maybe later—he also attended the School of Applied Art in Battle Creek, Michigan.

Sometime in the next ten years, George died, and the family’s fortunes declined. By 1930, they had moved into a rental, and Ralph took a new job—as an organizer and salesman for a fraternal order. The monthly rent was a rather steep $25, but the house had to be big enough to fit Ralph, his mother (who was not working), his sister Iris. Iris had just married a marine engineer, James C. Barrie, but he was at sea when the 1930 census was conducted. Nonetheless, the artistic spirit continued to flow through the family. Iris listed her occupation as poet—a brave choice, indeed!

Ralph would live in Portland until his death in 1974, going from Bohemian to Beatnik to Hippie. The Oregon Journal reported in 1970, “He has been a familiar figure in the SW Park Blocks for years—tall, silver-haired, simply but neatly dressed, and always barefoot. You usually see him on a park bench, sucking on his pipe, as he reads his latest library book, all the while absent-mindedly wriggling his toes.”

During the next decade—if not before—Ralph’s professional world expanded. Probably he received his first real exposure doing Western scenes for the Portland-based magazine “Northwest Background.” At least, he did seem to publish in this magazine, and this work was the most traditional, his later pieces indicating extensive experimentation, which takes time. In the mid-1930s he became intrigued by Buddhism and travelled to Buddhist temples in San Francisco and Los Angeles; for a time he was director of something he called “American Buddhist Society.” Likely this was the American Buddhist Society and Fellowship, founded in 1945 by Robert Ernst Dickhoff, who would later try to link UFOs to Buddhist mythology. (Phillips’s connection to Buddhism seemed to attenuate some over the years: in a 1949 form for the Portland Museum of Art, he made the connection prominent, but he told the Oregon Journal in 1948 he no longer had formal connections to Buddhism.)

Phillips seems to have had a long-standing interest in H.P. Lovecraft and Weird Tales, and this was reflected in his art by the 1940s, when he started to call himself a painter of the “Ultra Weird.” He explained this as “mystic, occult, weird, macabre, psychic-inspired.” He also called his work “modern,” which may have been a nod to the likes of Picasso, although it cut across genres. A few times, at least, he blended his mysticism with his Western scenery, creating images of Native Americans that he thought would interest Spiritualists, who sometimes used Indians as spirit guides.

His methods were occult, too. He tried to get himself into a detached state of mind so that he could receive inspiration from what he called “the invisible world.” He worked at night, when he could see (imagine?) strange faces and alien presences outside his window. Sometimes, the images—and titles—came to him fully formed. His work was often abstract, but—signs of Fort, occasionally had unexpected clarities. He told the Oregon Journal, “I start a picture with no idea what the finished product will be. Often it turns out to be a colorful network of lines, but somewhere in the picture will appear a cat carrying a kitten. Weird, isn’t it?”

The technique and subject matter can sound like a parody of those who uncharitably criticized abstract expressionism—created around the same time that Phillips was working—as something a kid could doodle. But Phillips didn’t see it that way. “Any Tom, Dick, and Harry can paint what he sees, but few can do my type of work.”

Phillips sold paintings to Weird Tales and fanzines; he displayed at science conventions in Los Angeles (1946) and Philadelphia (1947). Robert Bloch, author of Psycho and another devotee of Lovecraft, owned some of his work, as did Erle Korshak, a Chicago science fiction fan who co-founded Shasta Publishing.

How Phillips became involved with the Bay Area Fortean community is unclear. In the late 1940s, he was renting an 8x10 room in a mansion near the corner of SW 12th Avenue and Clay in Portland, where his “favorite friend” was an owl that lived in the eaves. Perhaps he met Haas at a Buddhist temple? Perhaps he met some of the writers at one of the conventions? Perhaps they made contact with him to praise his works. (Haas, after all, was collecting Clark Ashton Smith’s art.) He also developed a fan in Chingwah Lee, an art dealer in San Francisco’s Chinatown and art critic. At any rate, it is known that by the late 1940s he was visiting the San Francisco Bay Area for artistic inspiration, meaning he had connections by then—just as Chapter Two was founded.