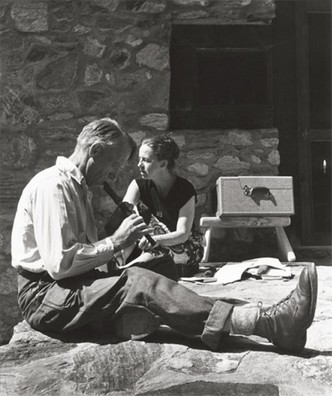

Scott and Helen Nearing, 1950.

Scott and Helen Nearing, 1950. A Fortean radical—though a Fortean mostly by admiration.

Scott Nearing may need to be introduced to the modern world, but for a time he was quite famous as a leftist and early advocate of the back-to-the-land movement. His life is well documented, by himself and his second wife, biographers, and historians. So I’ll keep the biographical portion of this relatively brief.

Nearing was born in Pennsylvania on 6 August 1883, almost a decade after Charles Fort and almost two decades before Tiffany Thayer. He lived a privileged life in coal country and attended Penn Charter School, where he was a classmate of future Fortean Society founder J. David Stern. As Stern recalled, the two worked together on a paper about the Fourier movement in America, but had to turn in separate essays because they could not agree on an interpretation: Nearing blamed the downfall of that early Utopian society on external factors, while Stern thought the silly ideas held by the members was to blame. It was a telling split, Stern going on to become a business liberal, friend of the New Deal, while Nearing—alone among his family—nurtured a sensitive social consciousness that would drive him to the left of socialism and toward a kind of primitivist anarchism.

Scott Nearing may need to be introduced to the modern world, but for a time he was quite famous as a leftist and early advocate of the back-to-the-land movement. His life is well documented, by himself and his second wife, biographers, and historians. So I’ll keep the biographical portion of this relatively brief.

Nearing was born in Pennsylvania on 6 August 1883, almost a decade after Charles Fort and almost two decades before Tiffany Thayer. He lived a privileged life in coal country and attended Penn Charter School, where he was a classmate of future Fortean Society founder J. David Stern. As Stern recalled, the two worked together on a paper about the Fourier movement in America, but had to turn in separate essays because they could not agree on an interpretation: Nearing blamed the downfall of that early Utopian society on external factors, while Stern thought the silly ideas held by the members was to blame. It was a telling split, Stern going on to become a business liberal, friend of the New Deal, while Nearing—alone among his family—nurtured a sensitive social consciousness that would drive him to the left of socialism and toward a kind of primitivist anarchism.

Nearing bounced around through Philadelphia Colleges. In 1908, he married Nellie Marguerite Seeds; they would have three sons. Eventually, Nearing graduating from the Wharton School of Business, with a Ph.D. in economics granted in 1909. He worked on the problem of child labor and also became a professor at Wharton himself. In 1915, he was summarily fired because of his leftist views—a case that would be of some moment to the radical left movement of the time. During World War I, he became a pacifist and continued to produce a steady stream of writings attacking war, nationalism, and capitalism. In 1917, he became a vegetarian, influenced in part by what he read in the magazine Physical Culture, as a younger man, and also by the barbarity of war: he reasoned that if it was wrong to kill people, it was wrong, as well, to kill animals.

His philippics got him noticed by the government and in 1919 he was put on trial for obstructing recruiting—the argument being that his ant-militaristic writings might turn off potential recruits. He was found not guilty, but the American Socialist Society, with which he was associated, was fined. During the 1920s, Nearing’s politics moved further left, adopting communism, but also looking beyond it to a kind of anarchism. Like Fort himself, Nearing did not want to be comfortable in any system, but always an outsider, a critic. He was not especially clear-eyed, though, when it came to Soviet Communism. In 1925, he and Nellie separated; that year, he also visited the Soviet Union and came away impressed with that country’s educational system. Two years later, he was in China, urging on the Communists there.

By the late 1920s, Nearing and Nellie had a farm in upstate New York, where they were practicing living the simple life: growing and eating their own foods, mostly raw, mostly fresh. Among those hanging around the farm was Helen Knothe, a Theosophist, vegetarian, and free-spirit with whom Nearing was having an affair, and with whom he worked on his writing. The farm also provided another Fortean connection: among those who attended was Yvette Szkely. At the time, she was having an affair of her own, with the Nearing’s oldest son, Johnny, but soon, aged only 17, when would become an object of lustful attraction to Theodore Dreiser, then about fifty. Dreiser, of course, helped discover, publish, and publicize Fort and the Fortean Society (at least at the beginning). The link between Nearing and Dreiser was not as direct as between Nearing and Stern, but still it’s there, an overlapping of social worlds.

In the 1930s, Nearing and Knothe visited the Soviet Union, again praising its development. Nearing’s son, John—who went by the name John Scott—had a more complicated view. After attending the University of Wisconsin, then known for its progressive educational style, he moved to the Soviet Union, went to work there, and raised a family—escaping just before the purges. Meanwhile, Scott and Helen established a farm in Vermont where they practiced self-reliance, growing their own food, making their own clothes, selling maple syrup and maple sugar. Like Hereward Carrington and other naturopathics, they practiced fasting—sometimes for more than a week—or simplified their diet tot he point that they would eat only one item—say, apples—for a fortnight or some other time period. Nearing continued to give lectures and write.

In 1943, he started publishing a regular pamphlet, called “World Events.” Nearing spoke out against World War II—which cost him some writing gigs. In 1947, he and Helen finally married. They wrote books together, advocating modern homesteading, and in the 1950s traveled around the world, once again seeing in the Soviet Union and Communist China solid, peaceful societies. It was around this time that the Nearings left Vermont because of development, and relocated to Maine.

The two would go on to live very long lives, much longer than the first iteration of the Fortean community, which more or less broke up in 1959. Nearing died in 1983, a few weeks after his hundredth birthday, making a conscious decision to end his life by no longer eating. Helen would live another twelve years, dying in 1995 from complications that arose after a car accident. She was 91.

As far as I can tell—and that may not be very far—Nearing never mentioned Fort. His writing is voluminous, though, and I certainly have not gone through all of it, so there may be a mention here or there, but Fort does not seem to have been central—or even important—to Nearing’s philosophy. There are other connections, though, ways one might see that Nearing at least knew of Fort’s writings and maybe appreciated them. Certainly, there are personal connections: Stern, maybe Dreiser, perhaps even Thayer. Thayer recalls one time when he was hanging out with some spiritualists and ghost hunters—Fred Keating, Hereward Carrington, Eric J. Dingwall—and included in the group was Scott Nearing. This was supposedly around 1940. There is no chance that in a group such as that one Thayer would not have been talking up Fort, and so, if that meeting actually happened, there can be no doubt that Nearing heard of Fort at least at that time.

I don’t have a great sense of Nearing’s religious views, but he does seem to have had some mystical inclinations, possibly an acceptance of spiritualism. Helen undoubtedly influenced him here, having grown up as a Theosophist and having had an earlier affair with the mystic Jiddu Krishnamurti. Helen quotes Scott as saying—regarding a question about the immortality of the soul—“I prefer to put the question differently: Does a man go on keeping company with the universe of which he is a part? I have come to the conclusion that life goes on for a substantial range of experiences which differ a great deal. Life is not simple, but complex, and one of its complexities is the division of life into fragments of longer or shorter duration, but certainly more durable than the apparatus with which we pursue life on this earth.”

Nearing seems to have had other connections to Thayer, if not close, then separated by only a single connection. In 1946, for example, Thayer recruited a Nearing follower to visit Ezra Pound in the hospital. And in 1950, when Thayer and a group of other Forteans had dinner with world citizen Garry Davis to induct him into the Society, Nearing was there. If nothing else, Thayer and Nearing shared a belief in non-conformity and the need to constantly question the given-account, which was also a point made repeatedly by Fort, and so there is a parallel between Nearing and Fort, perhaps independently derived rather than influence flowing in either direction, but a similarity nonetheless.

And Thayer saw this, whether or not Nearing did, appreciating the left libertarianism that was common among Forteans. He first mentioned Nearing in The Fortean 10 (fall 1944), when he made Nearing one of the earliest Honorary Founders (replacing the recently deceased Alexander Woollcott):

“Many younger Forteans will not remember when Scott Nearing was—in effect—fired from the faculty of the U. of Pennsylvania in 1915. He was the ‘Bertrand Russell’ of that day, and the cause of academic freedom has been his cause ever since. No ‘Party’ has ever been broad enough in its principles to hold him. No Party ‘Discipline’ has ever been strong enough to break his indomitable will. Year in, year out, he was lectured and written from the depths of a truly understanding heart and a brilliantly lucid, luminous mind . . . Scott Nearing is an Honorary Founder of the Fortean Society, and no living man is better entitled to every Fortean’s respect.

“Every month or oftener, a printed letter is now being issued from Washington, D.C., by a private group of enthusiasts, under the heading: ‘WORLD EVENTS, analyzed and interpreted by Scott Nearing.”

Thayer would go on to advertise “World Events” on the back page of Doubt for years and years. “Its value to you is that it views events in the perspective of history even as they occur. A very good Fortean habit,” he wrote in one endorsement. He would also promote a number of Nearing’s other publishing ventures—“Man’s Search for the Good Life” and, with Helen, a book on growing maple syrup; their joint book “The Brave New World”; and his “Revolution of our Time”: “You may not like the book’s implications or relish the course it points, but if you have lived through the past 20 years you must acknowledge its verity, and if you live through the next 20, you will probably see its projections made into history by the day. Order direct from the publishers. $1.00. Make checks payable to World Events, and address them to 125 Fifth Street, NE, Washington 2 DC.”

The Nearings may have been interested enough in the Society to send in clippings. Helen’s name appears once in a credit section, but it is unconnected to any particular item. And in Doubt 38 (October 1952), in a regular update on flying saucers—which he hated to do—Thayer noted that “World Events” had done an issue on UFOs. It is not clear whether the Nearings passed this on to Thayer, or he noted it in his usual reading. He was confused by the subject—he loathed flying saucers but adored Nearing— “The total take on SAUCERS for the period went up to 281 pieces, including a lead article in “World Events” by no less a meteorologist than Scott Nearing. It seems, an odd topic for Scott to write about, unless, as one suspects, at last the classic ‘twain’ have met.” What Thayer seems not to have known is that Helen was a devotee of flying saucer lore, a collector of books on the subject—no doubt an outgrowth of her Theosophy, as many Theosophists were interested in flying saucers, seeing them as connected to Madame Blavatsky’s speculative philosophy.

Thayer’s admiration for Nearing can be gleaned in his correspondence with Eric Frank Russell. In early 1950, there was that dinner for Garry Davis. In his write up for Doubt, Thayer noted, “We were particularly lucky to catch Scott Nearing between debates in Philadelphia and Brooklyn, at the end of the Vermont sugaring season. As a veteran campaigner for rational human relationships, and one who has solved the personal problem of living in self-respect under a shamefully organized economic system, Scott made available his life-time of experience toward the promotion of the ‘world-citizen’ concept.” He told Russell in May, privately, that Davis was an earnest man and he felt good for having gotten Davis and Nearing in contact. He came back to the subject in a letter the following month: Davis met Nearing “and so the world will be saved. You and I will be damned.”

That was an especially positive remark from Thayer, who dismissed almost every utopian visionary. Always the crank, he knew that he couldn’t quite by into the system—he was doomed an outsider—but he thought that Davis and Nearing were legitimately great people with legitimately valuable ideas worth pursuing. From Thayer, there was no higher praise.

His philippics got him noticed by the government and in 1919 he was put on trial for obstructing recruiting—the argument being that his ant-militaristic writings might turn off potential recruits. He was found not guilty, but the American Socialist Society, with which he was associated, was fined. During the 1920s, Nearing’s politics moved further left, adopting communism, but also looking beyond it to a kind of anarchism. Like Fort himself, Nearing did not want to be comfortable in any system, but always an outsider, a critic. He was not especially clear-eyed, though, when it came to Soviet Communism. In 1925, he and Nellie separated; that year, he also visited the Soviet Union and came away impressed with that country’s educational system. Two years later, he was in China, urging on the Communists there.

By the late 1920s, Nearing and Nellie had a farm in upstate New York, where they were practicing living the simple life: growing and eating their own foods, mostly raw, mostly fresh. Among those hanging around the farm was Helen Knothe, a Theosophist, vegetarian, and free-spirit with whom Nearing was having an affair, and with whom he worked on his writing. The farm also provided another Fortean connection: among those who attended was Yvette Szkely. At the time, she was having an affair of her own, with the Nearing’s oldest son, Johnny, but soon, aged only 17, when would become an object of lustful attraction to Theodore Dreiser, then about fifty. Dreiser, of course, helped discover, publish, and publicize Fort and the Fortean Society (at least at the beginning). The link between Nearing and Dreiser was not as direct as between Nearing and Stern, but still it’s there, an overlapping of social worlds.

In the 1930s, Nearing and Knothe visited the Soviet Union, again praising its development. Nearing’s son, John—who went by the name John Scott—had a more complicated view. After attending the University of Wisconsin, then known for its progressive educational style, he moved to the Soviet Union, went to work there, and raised a family—escaping just before the purges. Meanwhile, Scott and Helen established a farm in Vermont where they practiced self-reliance, growing their own food, making their own clothes, selling maple syrup and maple sugar. Like Hereward Carrington and other naturopathics, they practiced fasting—sometimes for more than a week—or simplified their diet tot he point that they would eat only one item—say, apples—for a fortnight or some other time period. Nearing continued to give lectures and write.

In 1943, he started publishing a regular pamphlet, called “World Events.” Nearing spoke out against World War II—which cost him some writing gigs. In 1947, he and Helen finally married. They wrote books together, advocating modern homesteading, and in the 1950s traveled around the world, once again seeing in the Soviet Union and Communist China solid, peaceful societies. It was around this time that the Nearings left Vermont because of development, and relocated to Maine.

The two would go on to live very long lives, much longer than the first iteration of the Fortean community, which more or less broke up in 1959. Nearing died in 1983, a few weeks after his hundredth birthday, making a conscious decision to end his life by no longer eating. Helen would live another twelve years, dying in 1995 from complications that arose after a car accident. She was 91.

As far as I can tell—and that may not be very far—Nearing never mentioned Fort. His writing is voluminous, though, and I certainly have not gone through all of it, so there may be a mention here or there, but Fort does not seem to have been central—or even important—to Nearing’s philosophy. There are other connections, though, ways one might see that Nearing at least knew of Fort’s writings and maybe appreciated them. Certainly, there are personal connections: Stern, maybe Dreiser, perhaps even Thayer. Thayer recalls one time when he was hanging out with some spiritualists and ghost hunters—Fred Keating, Hereward Carrington, Eric J. Dingwall—and included in the group was Scott Nearing. This was supposedly around 1940. There is no chance that in a group such as that one Thayer would not have been talking up Fort, and so, if that meeting actually happened, there can be no doubt that Nearing heard of Fort at least at that time.

I don’t have a great sense of Nearing’s religious views, but he does seem to have had some mystical inclinations, possibly an acceptance of spiritualism. Helen undoubtedly influenced him here, having grown up as a Theosophist and having had an earlier affair with the mystic Jiddu Krishnamurti. Helen quotes Scott as saying—regarding a question about the immortality of the soul—“I prefer to put the question differently: Does a man go on keeping company with the universe of which he is a part? I have come to the conclusion that life goes on for a substantial range of experiences which differ a great deal. Life is not simple, but complex, and one of its complexities is the division of life into fragments of longer or shorter duration, but certainly more durable than the apparatus with which we pursue life on this earth.”

Nearing seems to have had other connections to Thayer, if not close, then separated by only a single connection. In 1946, for example, Thayer recruited a Nearing follower to visit Ezra Pound in the hospital. And in 1950, when Thayer and a group of other Forteans had dinner with world citizen Garry Davis to induct him into the Society, Nearing was there. If nothing else, Thayer and Nearing shared a belief in non-conformity and the need to constantly question the given-account, which was also a point made repeatedly by Fort, and so there is a parallel between Nearing and Fort, perhaps independently derived rather than influence flowing in either direction, but a similarity nonetheless.

And Thayer saw this, whether or not Nearing did, appreciating the left libertarianism that was common among Forteans. He first mentioned Nearing in The Fortean 10 (fall 1944), when he made Nearing one of the earliest Honorary Founders (replacing the recently deceased Alexander Woollcott):

“Many younger Forteans will not remember when Scott Nearing was—in effect—fired from the faculty of the U. of Pennsylvania in 1915. He was the ‘Bertrand Russell’ of that day, and the cause of academic freedom has been his cause ever since. No ‘Party’ has ever been broad enough in its principles to hold him. No Party ‘Discipline’ has ever been strong enough to break his indomitable will. Year in, year out, he was lectured and written from the depths of a truly understanding heart and a brilliantly lucid, luminous mind . . . Scott Nearing is an Honorary Founder of the Fortean Society, and no living man is better entitled to every Fortean’s respect.

“Every month or oftener, a printed letter is now being issued from Washington, D.C., by a private group of enthusiasts, under the heading: ‘WORLD EVENTS, analyzed and interpreted by Scott Nearing.”

Thayer would go on to advertise “World Events” on the back page of Doubt for years and years. “Its value to you is that it views events in the perspective of history even as they occur. A very good Fortean habit,” he wrote in one endorsement. He would also promote a number of Nearing’s other publishing ventures—“Man’s Search for the Good Life” and, with Helen, a book on growing maple syrup; their joint book “The Brave New World”; and his “Revolution of our Time”: “You may not like the book’s implications or relish the course it points, but if you have lived through the past 20 years you must acknowledge its verity, and if you live through the next 20, you will probably see its projections made into history by the day. Order direct from the publishers. $1.00. Make checks payable to World Events, and address them to 125 Fifth Street, NE, Washington 2 DC.”

The Nearings may have been interested enough in the Society to send in clippings. Helen’s name appears once in a credit section, but it is unconnected to any particular item. And in Doubt 38 (October 1952), in a regular update on flying saucers—which he hated to do—Thayer noted that “World Events” had done an issue on UFOs. It is not clear whether the Nearings passed this on to Thayer, or he noted it in his usual reading. He was confused by the subject—he loathed flying saucers but adored Nearing— “The total take on SAUCERS for the period went up to 281 pieces, including a lead article in “World Events” by no less a meteorologist than Scott Nearing. It seems, an odd topic for Scott to write about, unless, as one suspects, at last the classic ‘twain’ have met.” What Thayer seems not to have known is that Helen was a devotee of flying saucer lore, a collector of books on the subject—no doubt an outgrowth of her Theosophy, as many Theosophists were interested in flying saucers, seeing them as connected to Madame Blavatsky’s speculative philosophy.

Thayer’s admiration for Nearing can be gleaned in his correspondence with Eric Frank Russell. In early 1950, there was that dinner for Garry Davis. In his write up for Doubt, Thayer noted, “We were particularly lucky to catch Scott Nearing between debates in Philadelphia and Brooklyn, at the end of the Vermont sugaring season. As a veteran campaigner for rational human relationships, and one who has solved the personal problem of living in self-respect under a shamefully organized economic system, Scott made available his life-time of experience toward the promotion of the ‘world-citizen’ concept.” He told Russell in May, privately, that Davis was an earnest man and he felt good for having gotten Davis and Nearing in contact. He came back to the subject in a letter the following month: Davis met Nearing “and so the world will be saved. You and I will be damned.”

That was an especially positive remark from Thayer, who dismissed almost every utopian visionary. Always the crank, he knew that he couldn’t quite by into the system—he was doomed an outsider—but he thought that Davis and Nearing were legitimately great people with legitimately valuable ideas worth pursuing. From Thayer, there was no higher praise.