Sam Youd was born 16 April 1922 in Lancashire. (His last name rhymes with crowd, not rude.) His father, Samuel—different than his son’s name, which was just Sam—worked in a factory. His mother, Harriet, had a hard-luck life: she had been widowed three times (and had three children) by the time she gave birth to Sam. Harriet was the head cook at the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst. Sam was the couple’s only child.

Youd attended Peter Symonds School (now College), in Winchester. When he was confirmed the the Church of England, he took the first name Christopher. Shortly after he finished school, he enlisted in the Royal Corps of Signals and was stationed in Gibraltar, North Africa, and Italy. In 1947, he married the Joyce Fairbairn. They would have five children, one son and four daughters. Immediately after the war, and just after his marriage, he tried to make a living on writing alone, but the few sales were not enough for material support and so he took a job doing publicity for the Diamond Corporation. The work was in contradiction to his personality, which was private and opposed to author’s acting as publicists for their own work. (That made them actors and actresses, he thought, not writers.)

In April 1939, Youd started putting out his own ‘zine, The Fantast. Whatever hard feelings there may have been with Clarke were blown over by now. He had an article in the first issue. (And Youd would cite him as a major influence on his own later work.) He would remained editor of the ‘zine through March 1941, nine issues in all, when he went to war and Douglas Webster took over four another five issues (through July 1942). By this point, Youd was using the byline CS Youd. (His earlier appearance in Novae Terrae had been as S. Youd.) The fan historian Harry Turner wrote, “Until the vicissitudes of wartime publishing in England became too great, The Fantast was the best illustrated, most literate, funniest and deepest thinking publication to emerge from the British Isles.” It’s an interesting description, as a portrait of Youd in the Fantast from about this time—also cited by Turner—notes, “His dislike of ‘intellectuals’—a class which includes a surprisingly varied assortment of people—has led him to become an inverted highbrow, praising the tastes of the general public and treating the less popular forms of art and entertainment with scorn.” Among the contributors to The Fantast was future Fortean Julian F. Parr.

Youd published some poetry in other ‘zines, and had some letters published in professional magazines, and apparently there may have been some articles when he just came through the war, but his first acknowledged professional sale came in 1949 with “Christmas Tree,” which appeared in the February issue of “Astounding.” He then appeared in the April issue with “Colonial.” Having settled in London, he was now close to the center of British fandom—his office was near the White Horse Pub where science fiction fans had their meetings. In a retrospective, he wrote, “On Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday and Friday evenings I took the train home to immerse myself in the sweat of literary endeavour. Thursday was freedom night: the office closed shortly before the White Horse opened for the evening and until the eleven o’clock closing time I sat on a stool by the bar, drinking beer and arguing about ... well, anything; even sometimes, despite a growing disillusionment with the genre, science fiction.”

In the late 1940s, he received a scholarship from the Rockefeller Foundation that allowed him to finish his first acknowledged novel (he may or may not have written one earlier), 1949’s “The Winter Swan.”Through the early 1950s, he continued to write short stories for the science fiction and fantasy magazines, under various pseudonyms, and a series of novels under the name Samuel Youd. He broke through with the 1956 novel “The Death of Grass,” which was published under the name “John Christopher.” Around this time, he had also been given a management position with his job and the combined forces let him relocate to Guernsey and, eventually, quit his publicity work to become a fill-time writer. There followed a succession of thematically similar novels, post-apocalyptic and dystopian. (Some of these were mentioned in fellow Fortean John Atkins’s “Tomorrow Revealed.”) As the Guardian noted in his obituary, Youd was often compared to another British science fiction writer, John Wyndham, who shared a publisher and an interest in catastrophic disasters.

There is a cache correspondence between Youd and Eric Frank Russell preserved in Russell’s papers at the University of Liverpool. These run from February 1947-early 1948, then resume in 1964, and give some further insight into Youd’s views. The very first letter comes int he middle of an already established correspondence, with Youd chiding Russell for having disparaged Italians and Jews, which had apparently caused Russell to react violently: “An excess of vehemence always seems unnecessary to me,” Youd replied, “on practical any subject, and your letter reads like a riot.”

He went on to point out that Russell’s views sat on a thine evidentiary base: the comments of some British troops who had been stationed in Italy, for instance. Youd pointed out that he’d been in Italy, too, and did not have the same opinions. And then he used a bit of Fortean jiu-jitsu on him: “Your position is about as valid as would be a science-fiction fan’s who said: ‘I’ve not read any Charles Fort, but I know he’s just a crazy idiot because all the fans at the Convention said he was.’ I know that it’s not easy for you to go and check up on Italy, as it would be for this hypothetical fan to read Fort, but at least you can practice your Forteanism by refusing to have a ready-made dogma about the nation.”

What really seems to have set the whole argument off, unsurprisingly, was N. V. Dagg and his publication “Tomorrow,” which had taken, by the accounts of other Forteans and even Thayer, an anti-Semitic turn. Apparently Youd had complained about the “racial strife” in his letter, which Russell took as a personal attack, but which Youd meant as “a general criticism of the tone of the magazine. Maybe it should have been directed to Dagg rather than you, but I don’t feel like wasting a stamp on Dagg. And presumably you like the magazine or you wouldn’t write so many articles for them. Yu say we’re all nuts. Perhaps we are, but some of us are nuts in ways that do less damage to others. Anti-Semitic nuts does [sic] a hell of a lot more damage than science-fiction nuts (say).” Youd went so far as to admit that he didn’t like Jewish people himself, but thought that “very likely my fault.” It was a level of introspection that was often alien to Russell and Thayer. Youd continued to criticize Dagg and Tomorrow the next month, but admitted that Russell might be wearied of the subject.

Suggesting that Youd’s self-conception—that nothing should cause one to get to worked up—was right, he continued on with Russell, despite their disagreements, asking when Russell would be in town for a visit, seeking advice on literary agents, and wondering if Campbell would barter for stories rather than paying. There were things in America that money could just not by in post-War England—Joyce wanted nylons, for example—and Youd was hoping Campbell would provide. (Russell told him this was naive; take the cash.) At the time—mid 1948—the Youds were struggling, Sam making a pittance writing and otherwise looking for a job (he’d been shot down doing advertising for meat, soft drinks, and ice cream), Joyce paying the bills with what she made from editing work.

Even after he began selling books, though, living was tight; the cost of having five children. In April 1964, he admitted that Thayer and Russell were probably right in how best to structure an author’s life, but couldn’t see how he could manage: “I think you and Thayer are right in feeling that a separate office, well away from home, would help a lot towards making life easier. The difficulty is that this is an under-capitalized profession. With five little odds and sods to feed, clothe, educate and such, I don’t find myself with the means of indulging in anything that can remotely be described as a luxury, as far as writing is concerned. And I have, so far, managed to get books written despite various domestic catastrophes.” He continued to seek advice on agents, especially American ones, both from Russell and Arthur Clarke, who remained a friend, as well as others too, probably. (In addition, he and Russell gave each other advice about how to handle the Scott Meredith Agency, which they viewed with some measure of distrust.)

In the late 1960s, Youd turned to young-adult literature, for which he may be best remembered. Some of these books would be adapted for television in the 1980s. In 1978, Sam and Joyce divorced. Youd married Jessica Ball, who preceded him in death, passing 2001.

Sam Youd died 3 February 2012. He was 89.

*********************

As in most cases, I cannot specify exactly when Youd met Fort, though it seems it may have been through Russell. There’s a cryptic passage in Youd’s response to Arthur C. Clarke that suggests Russell was a Fortean as early as late 1937, and that Youd was aware of it. Clarke had attacked Donald Wandrei’s “Colossus” for mis-using the Lorentz-Fitzgerald Contraction Theory. Youd responded, “Does that really matter? After all, to followers of those two latter day Aristotles, Russell and Fort, said theory is merely another example of scientific incompetence and ignorance—all true Russellians know that Alpha Centauri is a cosmic glow-worm and that the moon is made of fused wire-staples.”

I have no information on what Youd was doing, Fortean-wise, through the end of the ‘30s and the first half of the ‘40s. In 1947, though—at the same time he was arguing with Russell over anti-Semitism—he was introducing Fortean ideas into his ‘zine. On 5 February 1947, he wrote Russell that he would be running a piece by him. Russell thought it would be the one on the maverick Italian astronomers Pollini and Azzario, who had been featured in Doubt, but it wasn’t. (That piece, or one like it, would run in James Blish’s ‘zine.) Instead, Youd ran “Fort the Colossus,” which had previously appeared in the ‘zine Spaceways. (He also scheduled Russell’s story “Shades of Night.”)

Simultaneously, he continued to use Fort to try to argue Russell out of his racist views. Apparently, Russell had come back to Youd claiming that his views were on what the fifty-year old Pollini had told him. “Do you think that’s an argument,” Youd wrote, with what seems like incredulity. “And I thought Forteans were students of semantics! Hark now, if a Frenchman told you the English were a lot of low-grade punks, admitted he’d never been to England, but said the opinion was passed onto him by a 50-year old Englishman—what would you think? Certainly Pollini is entitled to form his own opinion of his countrymen, but shame on you for accepting it from him ready-made!”

The Youds—both Sam and Joyce—seem to have become official members of the Fortean Society right around this time. Reflecting some of the confusion in the Society as it became more firmly established and started trying for an international audience, Sam wrote on 17 April 1947, “J. and I have to date received 4 copies of the latest DOUBT. What are they trying to do—convert us? Apparently an arrangement was made to exchange copies of Doubt and Youds magazine, which may have accounted for some of the extras being sent to them: they got some for their signing up, some from Russell, and some from Thayer, too. Thayer wanted more, though. He wrote Russell in May, that he’d received the magazine, but wanted a wedding photo, too. “The publicity is good for us, but a laugh is better.” Russell passed the information on (the request may have been made more than once), and Youd responded to one of these that he appreciated the request but they did not have any suitable glossies; “I’ll carry my little AGFA around and take snaps of us all over the place. When we get a good one I’ll send it to you or TT.

Meanwhile, somehow Sam became entangled with the a Fortean imbroglio. An Austrian living in England, Fred Weiss, had gotten the idea to film Fort’s books. Thayer was not keen on the idea and it seems that Russell was sour on Weiss. Youd tried to smooth over feelings and pump for the idea. He admitted that the man Weiss had tapped to do the filming, Rene Clair, was probably wrong for the job, as he was best known as a satirist. “This being so,” he wrote Russell in a letter dated 9 June 1948, he hardly seems the kind of man who could have done justice to Fort, as probably he and Thayer realised (he when he finally read the Books). Don’t tell me Fort is a satirist, either—it’s not the same kind of satire.” But then he went on to encourage Russell to reach out to Weiss—saying that he was looking for excuses not to like the man, who was, after all, a committed anti-dogmatist.

And he expressed amazement at Thayer’s approach—which was to dissuade the whole project by making it prohibitively expensive. Anyone who would pay up that kind of dough, he said, was a “Hollywood pimp” who would ruin an adaptation. “But surely where an honest pro-Fortean attempt is projected sympathy should be the real aim?” He noted that Weiss was approaching Thayer again, directly, and that Youd was, too, but diplomatically. As it happened, of course, nothing came of the plans.

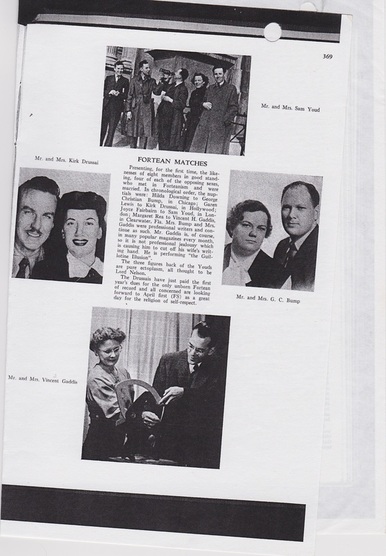

Still, the diplomacy must have worked. Thayer liked the Youds. They re so “sweet,” he commented to Russell,they “must be partly american.” Proving how much the anti-Semitic and pro-monarchy turn in Tomorrow had irritated even him, Thayer added in parentheses: “tell Dagg.” And when they finally sent in their picture, Thayer was happy. He joked with Russell: “The Youds sent photo. They are beautiful—but not as pretty as you and I.” The photo—and the publicity that Thayer was planning—was displayed in Doubt 24 (April 1949). Thayer was trying to show that Forteanism was a movement affecting the very core institutions of society, including marriage: that Forteans were marrying, and begetting Fortean children. A new world was on the horizon.

In that issue, he wrote a column titled “Fortean Matches,” showed discussed four Fortean marriages and gave the pictures of the happy couples. It’s not clear to me how much of a Fortean Joyce was (or, for that matter, Hilda Downing), since I have not otherwise seen her mentioned in the magazine or any other references to her having an interest in Fort beyond receiving some copies of Doubt in her name (as Youd implied in the letter to Russell from April 1947). At any rate, Thayer wrote, “Presenting, for the first time, the likenesses of eight members in good standing, four of each of the opposite sexes, who met in Forteanism and were married. In chronological order, the nuptials were: Hilda Downing to George Christian Bump, in Chicago; Garen Lewis to Kirk Drussai, in Hollywood; Joyce Faribairn to Sam Youd, in Lodnin; Margaret Rea to Vincent H. Gaddis, in Clearwater, Fla. Mrs. Bump and Mrs. Gaddis were professional writers and continue as such. Mr. Gaddis is, of course, in many popular magazines every month, so it is not professional jealousy which is causing him to cut off his wife’s hand. He is performing ‘the Guillotine Illusion.’ The three figures back of the Youds are pure ectoplasm, all thought to be Lord Nelson. The Drussais have just paid the first year’s dues for the only unborn Fortean of record and all concerned are looking forward to April first (FS) as a great day for the religion of self-respect.”

As it happened, that was the only time either of the Youds appeared in Doubt. Already by that time, they seem to have dropped out of the Society. In January of 1949, Thayer wrote Russell noting that the address he had for them was no longer correct. He said the same in February. Now, it ma be that the confusion over the address was eventually corrected—there’s no mention of them in any subsequent correspondence between Russel and Thayer, either. But it is entirely possible, too, that the Youds belong to the group of Forteans who showed interest int he Society during the late 1940s, but not into the 1950s. Sam was starting to make money writing—as well as being kept busy with his day job—and there family was growing, which would have occupied a lot of their time. Probably Thayer’s vehemence on matters political would have been a turn off to the good-natured Sam Youd, as well, if not also to Joyce.

In that same April 1947 letter, Youd had demonstrated a very Fortean imagination. He told Russell, “We went to the Zoo yesterday. Such strange animals—you’d never believe! We saw one monstrosity that was labelled ‘giraffe’—but I think it’s Fortean . . .” There was, on display, an ability to still find wonder in a world that seemed regimented and named. Fort had also led him to question his own certainties on the matters of race and ethnicities—to not trust his own predilections. That’s a difficult thing to do, and so even if Sam Youd dropped Fort (or at least the Fortean Society) in the 1950s, he had once used Forteanism to open his own mind.