A 1938 book party at the Algonquin Hotel. Seated left to right: Fritz Foord, Wolcott Gibbs, Frank Case and Dorothy Parker. Standing: Alan Campbell, St. Clair McKelway, Russell Maloney and James Thurber.

A 1938 book party at the Algonquin Hotel. Seated left to right: Fritz Foord, Wolcott Gibbs, Frank Case and Dorothy Parker. Standing: Alan Campbell, St. Clair McKelway, Russell Maloney and James Thurber. A behind-the-scenes kind of Fortean.

Russell Vincent Maloney was born 26 June 1910 in Brookline Massachusetts to Vincent Paul Maloney and Alta V. Brooks. He was the eldest of three children, followed by a brother—Vincent Paul Jr.—and a sister—Alta. I don’t know why the two younger children were named after the parents, but Russell only carried his father’s middle name. He grew up in Newtown. The parents had come from the Midwest—Vincent born in Kansas, Alta in Missouri. Vincent senior was an advertising manager for the Boston Globe. (Alta had once worked for the Kansas City Star; and her father had been a peripatetic newspaper publisher—practitioner of what Fortean Harry Leon Wilson called “a good loose trade.”)

Maloney attended Mason Grammar School, Newtown High School, and then matriculated at Harvard in 1928. The Freshmen Red Book has him as broad-faced with close-cropped hair and perfectly circular glasses. That year, he was associated with the University Dramatic Club. He majored in English literature and hoped to follow his father into advertising—not unlike Thayer himself, then, born a few years earlier, bitten by the theater bug, making a career in advertising. And like Thayer Maloney became a writer—which was, however, his sole occupation.

Russell Vincent Maloney was born 26 June 1910 in Brookline Massachusetts to Vincent Paul Maloney and Alta V. Brooks. He was the eldest of three children, followed by a brother—Vincent Paul Jr.—and a sister—Alta. I don’t know why the two younger children were named after the parents, but Russell only carried his father’s middle name. He grew up in Newtown. The parents had come from the Midwest—Vincent born in Kansas, Alta in Missouri. Vincent senior was an advertising manager for the Boston Globe. (Alta had once worked for the Kansas City Star; and her father had been a peripatetic newspaper publisher—practitioner of what Fortean Harry Leon Wilson called “a good loose trade.”)

Maloney attended Mason Grammar School, Newtown High School, and then matriculated at Harvard in 1928. The Freshmen Red Book has him as broad-faced with close-cropped hair and perfectly circular glasses. That year, he was associated with the University Dramatic Club. He majored in English literature and hoped to follow his father into advertising—not unlike Thayer himself, then, born a few years earlier, bitten by the theater bug, making a career in advertising. And like Thayer Maloney became a writer—which was, however, his sole occupation.

“In the dreadful summer of 1932,” he recounted years later, The New Yorker “paid me ten dollars for an anecdote. I was ripe for seduction, as it happened, having been given two prizes by Harvard for thesis on the fiction-writing methods of Aldous Huxley. In addition to medals and scrolls (one of which, I remember, mentioned my ‘contributions to useful and polite literature’) there were cash prizes totaling four hundred and fifty dollars. That, and the New Yorker’s check, made me think; and my father’s suggestion that I might plan on writing ‘after I got home from work’ fell, as they say, on deaf ears. One of the gossip columns in the Boston newspapers informed me that the New Yorker artists did not always think up their own ideas for pictures, that the management paid outsiders for suggestions. I sent in an account of a situation that I thought would make a good Helen Hopkinson picture—a lady librarian handing over a book to a patron with the admonishment, ‘Now don’t take this too literally, it’s symbolism’—and got paid for that: seven dollars. After that, of course, there was no question of working. I sent batches of drawing ideas to the New Yorker, and enough were accepted to take care of my frugal wants. Two years later I moved to New York, simply to save postage.”

Maloney arrived with just two suitcases, and was given a job working at The New Yorker in 1935. Fortunate, to say the least, given the state of the economy. At the time, James Thurber, the humorist who had been responsible for The New Yorker’s “Talk of the Town” feature was less often coming into the offices, having made a name for himself and doing his own writing. Maloney took over that job, in time, in addition to writing profiles and essays—‘casuals,’ as they called the at the New Yorker—and other pieces. He was especially interested in in theater, and wrote a lot about that. He was not so positive toward John Steinbeck or Ernest Hemingway, however—although he did go out of his way in his casuals to make clear he did not want to pick a fight with Hemingway, scared as he was of the author. He was an outstanding rewrite man, putting the New Yorker finish on metric tons of prose.

Maloney did the circuit: he was interested in celebrity and gossip, and made the rounds. He became friendly with Alfred Hitchcock and perhaps Ben Hecht—the first disciple of Charles Fort—who wrote for Hitchcock. He could be seen at the Algonquin Hotel and so likely knew Alexander Woollcott, another Fortean. He also seems to have known Thayer. In 1938, he eloped with the actress Miriam Battista. They had a child in 1945, Amelia. He edited the New Yorker’s in-house gossip rag during the War, The Conflict.

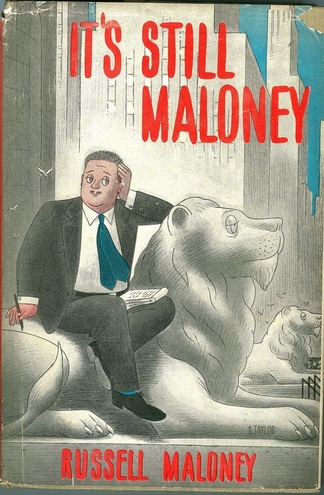

For all that Maloney was well known about New York, and a staff writer for the New Yorker since he was barely out of college, he doesn’t seem to have felt like he fit in. His collection of pieces from the magazine, It’s Still Maloney has a defensive, even bitter edge to it—proud of how strong the editorial tradition was at the New Yorker but also noting that while he did lots of writing—millions of words—he never got the recognition he craved, overshadowed by E. B. White and James Thurber. Brendan Gill, a friend and successor at the magazine, thought that his Irish Catholic roots made him feel an outsider there and at Harvard. His name sounded funny; his face looked babyish. Gill notes that the title It’s Still Maloney echoed Rube Goldberg’s quip that no matter how you slice it, it’s still baloney: self-mocking trending toward self-loathing. Another New Yorker colleague, Carl Rose, caught both Maloney’s skills and his anonymity: “The two best gagmen in the world, for my money are E.B. White and Russell Maloney…for a couple of years he sold an incredible number of picture ideas to The New Yorker and has been represented anonymously by most of the regular contributors to the magazine.”

After ten years—2,600 anecdotes and millions of words—Maloney left the New Yorker. At the time, he attributed his leaving to being burned-out. Gill thinks there was bitterness—that he hadn’t become famous, that he was shouldering so much work. He tried to distance himself from the New Yorker, ceding his complete collection of the magazine to Gill. But he continued to write for a number of publications—the New York Times, the Atlantic Monthly, Coronet (where fellow Fortean R. DeWitt Miller also write), The Saturday Review, Collier’s, and likely elsewhere. He also wrote under the pseudonyms Nosmo King (foreshadowing the later Fortean Nopar King); J J O’Malley; Arthur Canfield; and Barbara Anne Fuller. He also did related work—metaphorically following Alexander Woollcott onto the radio—doing reviews for CBS and appearing on talk shows. He and his wife produced a Broadway musical of The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, but it flopped, closing after only twelve weeks.

Always a big man, Maloney joked about his blood pressure several times in the New Yorker. It proved prophetic. In 1948, aged only thirty eight, he died of a cerebral hemorrhage.

It was in the course of doing his job with the New Yorker that Maloney came into contact with Thayer. That was around 1940, and the magazine was considering doing a profile on Thayer, in the manner that Maloney did them on Orson Welles and Alfred Hitchcock. They met for a couple of interviews, but Maloney determined that Thayer was too eccentric, and plans for the profile were scrapped. Likely it was at that time that Thayer recruited Maloney to the Fortean Society, although he did not get mentioned for a number of years—and, in the end, there were only two references to him. The first dealt with a “Talk of the Town” item in March 1946 about the naming of plants. The piece quoted an expert saying 350,000 plants had been discovered, and there were probably 150,000 yet unknown. Thayer was sure Maloney was slyly making a Fortean point and mocking the expert—how could the botanist know how many undiscovered plants there were? They were undiscovered! The next mention came two years later and was an obituary: “MFS Russell Maloney, who made the New Yorker much funnier than it is likely to be again for some time, died, Fort 20, 18 FS.”

How Maloney came to Fort is harder to specify. It seems that he probably knew of Fort before he met Thayer, and so was open to joining the Society. He notes that his brother was a dabbler in the occult, and so may have pointed Russell to the various books (before they were compiled into an omnibus edition). He may have heard about them from Hecht or from Wollcott, too. Maloney—as we will see—was a dyed in the wool Fortean, but he left no comment on him, and so one can only guess that at least part of the appeal was Fort’s humor. If he saw reviews of Lo!, which was widely publicized in 1931, while Maloney was attending Harvard, he may have picked up the book on his own—perhaps all the books, perhaps just the one, perhaps the omnibus edition in 1941.

Maloney, though, whatever his views on Fort, had little truck with Thayer or the Fortean Society. He took the time to read issue 7 of The Fortean Society Magazine, published June 1943, with the soon-to-be notorious article “Socratic Method.” The article was enough to have Thayer’s friend Aaron Susan quit the Society and Thayer reconsider its direction. On 20 July Maloney, Maloney passed the issue to the New York Field Division of the FBI. Attached to the issue was a letter—which seems to be missing—in which Maloney, as the FBI put it, said the article was “obviously the work of a man who is more of a crank than a skilled propagandist.” The FBI noted the issue, and that Thayer’s Fortean writings had come to the Bureau’s attention in the past, but otherwise did not act.

But for all his dislike of Thayer (and the Society), Maloney seemed to have absorbed some of Fort’s thoughts—or his work paralleled Fort’s in ways that Forteans such as Thayer could obviously see. For example, to combat obviously ridiculous legislation and court orders, Maloney suggested creating a Bureau of Homeric Laughter—a most Fortean idea, and in keeping with the government’s mad frenzy to create an alphabet soup of agencies. The BHL, he thought it should be called—making fun of government the way Fort poked holes in scientific scholarship. He wasn’t a baseball fan, another fact about which he felt self-conscious, and, in defense, he found a way to make others doubt whether the sport even existed: when they asked him what he thought about what’d just happened in the ‘thoid’ inning, he’d reply, there was no game—it’d been rained out. The obviously stunned questioner would point out the game was being broadcast on the radio at that very moment, and Maloney would knowingly reply that, well, the sponsors needed something to fill the air time: again, a very Fortean response to a difficult predicament, making the source of his discomfort disappear in doubt.

Maloney also wrote light fantasies, species of science fiction before science fiction was an accepted part of the slicks. (Or perhaps science fiction was always included in the slicks, in one way or another, and the breakthrough attributed to Heinlein is more a self-serving story of success for science fictionists than a reflection of reality.) It may be that Maloney was familiar with science fiction, which is another way that he might have come across Fort, whose Lo! was excerpted in Astounding. These stories had a Fortean—puckish—humor. In one tale, told from an imagined future, television had brought the world together and solved its ills, until, once, Orson Welles cursed on TV and bluenoses had the whole operation shut down. Another discussed the future of music, with records no longer albums of music but sound effects.

Indeed, his most famous piece—the one for which, momentarily, he stepped out of the background and found a bit of fame—is a science fiction tale published in the New Yorker. Called “Inflexible Logic,” the story builds from the so-called “infinite monkey theorem,” which was popularized earlier in the century. According to that hypothetical, a number of monkeys—or chimpanzees—banging on typewriters would, given enough time, reproduce the works of Shakespeare down to the last comma. It was a way of visualizing statistical processes. Maloney’s story, though, in true Fortean fashion, smashed this statistical view of the universe against the chaos of individuality. A rich man decides he should test the theory, and, to his surprise, the six chimpanzees he sets in front of typewriters, begin reproducing the great works of literature immediately, title pages and all. One even writes Samuel Pepys’s diary with all the naughty bits that had been abridged out of the rich man’s own edition. A scientist, unable to cope with this development, the violation of statistical laws, shoots all six chimps, while being shot himself. That is the one unpredictable force of the universe, the actions of people, even if they serve to recalibrate the laws of nature, to set them back on track.

As Gill noted, the story had a personal reflection—Maloney, the typing chimp, producing one piece of literature after another, unacknowledged—but it also proved popular. H. Allen Smith—the journalist who had covered Fort and the founding of the Fortean Society, finding it all so much fooferall—wanted the story for the anthology he edited Desert Island Decameron and offered to pay $25. Maloney refused the amount—too low—and was left out (again!) of a book that included the likes of Alexander Woollcott and James Thurber. It did make it into other collections, though, of mathematical fiction, and a Ray Bradbury edited anthology that was frequently republished. He even received praise from the quarters he most cherished: E. B. White (and Katharine White) included the story in the 1941 compendium A Subtreasury Of American Humor, where his name was featured alongside Thurber and Twain and many other famous authors.

Maloney arrived with just two suitcases, and was given a job working at The New Yorker in 1935. Fortunate, to say the least, given the state of the economy. At the time, James Thurber, the humorist who had been responsible for The New Yorker’s “Talk of the Town” feature was less often coming into the offices, having made a name for himself and doing his own writing. Maloney took over that job, in time, in addition to writing profiles and essays—‘casuals,’ as they called the at the New Yorker—and other pieces. He was especially interested in in theater, and wrote a lot about that. He was not so positive toward John Steinbeck or Ernest Hemingway, however—although he did go out of his way in his casuals to make clear he did not want to pick a fight with Hemingway, scared as he was of the author. He was an outstanding rewrite man, putting the New Yorker finish on metric tons of prose.

Maloney did the circuit: he was interested in celebrity and gossip, and made the rounds. He became friendly with Alfred Hitchcock and perhaps Ben Hecht—the first disciple of Charles Fort—who wrote for Hitchcock. He could be seen at the Algonquin Hotel and so likely knew Alexander Woollcott, another Fortean. He also seems to have known Thayer. In 1938, he eloped with the actress Miriam Battista. They had a child in 1945, Amelia. He edited the New Yorker’s in-house gossip rag during the War, The Conflict.

For all that Maloney was well known about New York, and a staff writer for the New Yorker since he was barely out of college, he doesn’t seem to have felt like he fit in. His collection of pieces from the magazine, It’s Still Maloney has a defensive, even bitter edge to it—proud of how strong the editorial tradition was at the New Yorker but also noting that while he did lots of writing—millions of words—he never got the recognition he craved, overshadowed by E. B. White and James Thurber. Brendan Gill, a friend and successor at the magazine, thought that his Irish Catholic roots made him feel an outsider there and at Harvard. His name sounded funny; his face looked babyish. Gill notes that the title It’s Still Maloney echoed Rube Goldberg’s quip that no matter how you slice it, it’s still baloney: self-mocking trending toward self-loathing. Another New Yorker colleague, Carl Rose, caught both Maloney’s skills and his anonymity: “The two best gagmen in the world, for my money are E.B. White and Russell Maloney…for a couple of years he sold an incredible number of picture ideas to The New Yorker and has been represented anonymously by most of the regular contributors to the magazine.”

After ten years—2,600 anecdotes and millions of words—Maloney left the New Yorker. At the time, he attributed his leaving to being burned-out. Gill thinks there was bitterness—that he hadn’t become famous, that he was shouldering so much work. He tried to distance himself from the New Yorker, ceding his complete collection of the magazine to Gill. But he continued to write for a number of publications—the New York Times, the Atlantic Monthly, Coronet (where fellow Fortean R. DeWitt Miller also write), The Saturday Review, Collier’s, and likely elsewhere. He also wrote under the pseudonyms Nosmo King (foreshadowing the later Fortean Nopar King); J J O’Malley; Arthur Canfield; and Barbara Anne Fuller. He also did related work—metaphorically following Alexander Woollcott onto the radio—doing reviews for CBS and appearing on talk shows. He and his wife produced a Broadway musical of The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, but it flopped, closing after only twelve weeks.

Always a big man, Maloney joked about his blood pressure several times in the New Yorker. It proved prophetic. In 1948, aged only thirty eight, he died of a cerebral hemorrhage.

It was in the course of doing his job with the New Yorker that Maloney came into contact with Thayer. That was around 1940, and the magazine was considering doing a profile on Thayer, in the manner that Maloney did them on Orson Welles and Alfred Hitchcock. They met for a couple of interviews, but Maloney determined that Thayer was too eccentric, and plans for the profile were scrapped. Likely it was at that time that Thayer recruited Maloney to the Fortean Society, although he did not get mentioned for a number of years—and, in the end, there were only two references to him. The first dealt with a “Talk of the Town” item in March 1946 about the naming of plants. The piece quoted an expert saying 350,000 plants had been discovered, and there were probably 150,000 yet unknown. Thayer was sure Maloney was slyly making a Fortean point and mocking the expert—how could the botanist know how many undiscovered plants there were? They were undiscovered! The next mention came two years later and was an obituary: “MFS Russell Maloney, who made the New Yorker much funnier than it is likely to be again for some time, died, Fort 20, 18 FS.”

How Maloney came to Fort is harder to specify. It seems that he probably knew of Fort before he met Thayer, and so was open to joining the Society. He notes that his brother was a dabbler in the occult, and so may have pointed Russell to the various books (before they were compiled into an omnibus edition). He may have heard about them from Hecht or from Wollcott, too. Maloney—as we will see—was a dyed in the wool Fortean, but he left no comment on him, and so one can only guess that at least part of the appeal was Fort’s humor. If he saw reviews of Lo!, which was widely publicized in 1931, while Maloney was attending Harvard, he may have picked up the book on his own—perhaps all the books, perhaps just the one, perhaps the omnibus edition in 1941.

Maloney, though, whatever his views on Fort, had little truck with Thayer or the Fortean Society. He took the time to read issue 7 of The Fortean Society Magazine, published June 1943, with the soon-to-be notorious article “Socratic Method.” The article was enough to have Thayer’s friend Aaron Susan quit the Society and Thayer reconsider its direction. On 20 July Maloney, Maloney passed the issue to the New York Field Division of the FBI. Attached to the issue was a letter—which seems to be missing—in which Maloney, as the FBI put it, said the article was “obviously the work of a man who is more of a crank than a skilled propagandist.” The FBI noted the issue, and that Thayer’s Fortean writings had come to the Bureau’s attention in the past, but otherwise did not act.

But for all his dislike of Thayer (and the Society), Maloney seemed to have absorbed some of Fort’s thoughts—or his work paralleled Fort’s in ways that Forteans such as Thayer could obviously see. For example, to combat obviously ridiculous legislation and court orders, Maloney suggested creating a Bureau of Homeric Laughter—a most Fortean idea, and in keeping with the government’s mad frenzy to create an alphabet soup of agencies. The BHL, he thought it should be called—making fun of government the way Fort poked holes in scientific scholarship. He wasn’t a baseball fan, another fact about which he felt self-conscious, and, in defense, he found a way to make others doubt whether the sport even existed: when they asked him what he thought about what’d just happened in the ‘thoid’ inning, he’d reply, there was no game—it’d been rained out. The obviously stunned questioner would point out the game was being broadcast on the radio at that very moment, and Maloney would knowingly reply that, well, the sponsors needed something to fill the air time: again, a very Fortean response to a difficult predicament, making the source of his discomfort disappear in doubt.

Maloney also wrote light fantasies, species of science fiction before science fiction was an accepted part of the slicks. (Or perhaps science fiction was always included in the slicks, in one way or another, and the breakthrough attributed to Heinlein is more a self-serving story of success for science fictionists than a reflection of reality.) It may be that Maloney was familiar with science fiction, which is another way that he might have come across Fort, whose Lo! was excerpted in Astounding. These stories had a Fortean—puckish—humor. In one tale, told from an imagined future, television had brought the world together and solved its ills, until, once, Orson Welles cursed on TV and bluenoses had the whole operation shut down. Another discussed the future of music, with records no longer albums of music but sound effects.

Indeed, his most famous piece—the one for which, momentarily, he stepped out of the background and found a bit of fame—is a science fiction tale published in the New Yorker. Called “Inflexible Logic,” the story builds from the so-called “infinite monkey theorem,” which was popularized earlier in the century. According to that hypothetical, a number of monkeys—or chimpanzees—banging on typewriters would, given enough time, reproduce the works of Shakespeare down to the last comma. It was a way of visualizing statistical processes. Maloney’s story, though, in true Fortean fashion, smashed this statistical view of the universe against the chaos of individuality. A rich man decides he should test the theory, and, to his surprise, the six chimpanzees he sets in front of typewriters, begin reproducing the great works of literature immediately, title pages and all. One even writes Samuel Pepys’s diary with all the naughty bits that had been abridged out of the rich man’s own edition. A scientist, unable to cope with this development, the violation of statistical laws, shoots all six chimps, while being shot himself. That is the one unpredictable force of the universe, the actions of people, even if they serve to recalibrate the laws of nature, to set them back on track.

As Gill noted, the story had a personal reflection—Maloney, the typing chimp, producing one piece of literature after another, unacknowledged—but it also proved popular. H. Allen Smith—the journalist who had covered Fort and the founding of the Fortean Society, finding it all so much fooferall—wanted the story for the anthology he edited Desert Island Decameron and offered to pay $25. Maloney refused the amount—too low—and was left out (again!) of a book that included the likes of Alexander Woollcott and James Thurber. It did make it into other collections, though, of mathematical fiction, and a Ray Bradbury edited anthology that was frequently republished. He even received praise from the quarters he most cherished: E. B. White (and Katharine White) included the story in the 1941 compendium A Subtreasury Of American Humor, where his name was featured alongside Thurber and Twain and many other famous authors.