Far more interesting than his brief moment as a Fortean.

Although it’s through-a-glass darkly.

Russel Stewart Jaque was born 6 June 1898 in Kansas City, Missouri, to Joseph R. and Mary M. (Stewart) Jaque—yes, to Mary and Joseph. The Jaque name was carried to America a couple of generations back from Switzerland. Mary and Joseph wed in 1897, the year she turned 18, and he 35. They seem to have split shortly thereafter. In 1900, Mary and Russel lived with her parents, as well as another city, in Kansas City. Both Mary and Joseph went on to remarry, Marry wedding Hadley G. Chamberlain, a potter, on Christmas day 1908, in Alameda, California. That’s where they were living at the time of the next census, too, in Oakland. Also in the family home was Mary’s father and her daughter, Ruth. Mary and Hadley—some four years her junior—would go on to have five children together, four girls and a boy..

At some point, in the 1910s, though, the family found its way to Pueblo, Colorado, where Hadley worked as a watchmaker in a foundry and Jaque became a printer with E. W. Frick. According to a 1919 notice in “Inland Printer,” Frick had only relatively recently started his company and seems to have been using it, in part at least, to train students in the art. (The 1940 census reported Jaque had only completed one year of high school, and so this may have been a form of vocational education for him.) It was from here, in Pueblo, that Jaque registered for the draft on 12 September 1918. He was tall and slender with brown hair and eyes, according to his registration card. The war would end in a couple of months, Armistice Day coming on 11 November 1918 and Jaque was not be drafted.

Although it’s through-a-glass darkly.

Russel Stewart Jaque was born 6 June 1898 in Kansas City, Missouri, to Joseph R. and Mary M. (Stewart) Jaque—yes, to Mary and Joseph. The Jaque name was carried to America a couple of generations back from Switzerland. Mary and Joseph wed in 1897, the year she turned 18, and he 35. They seem to have split shortly thereafter. In 1900, Mary and Russel lived with her parents, as well as another city, in Kansas City. Both Mary and Joseph went on to remarry, Marry wedding Hadley G. Chamberlain, a potter, on Christmas day 1908, in Alameda, California. That’s where they were living at the time of the next census, too, in Oakland. Also in the family home was Mary’s father and her daughter, Ruth. Mary and Hadley—some four years her junior—would go on to have five children together, four girls and a boy..

At some point, in the 1910s, though, the family found its way to Pueblo, Colorado, where Hadley worked as a watchmaker in a foundry and Jaque became a printer with E. W. Frick. According to a 1919 notice in “Inland Printer,” Frick had only relatively recently started his company and seems to have been using it, in part at least, to train students in the art. (The 1940 census reported Jaque had only completed one year of high school, and so this may have been a form of vocational education for him.) It was from here, in Pueblo, that Jaque registered for the draft on 12 September 1918. He was tall and slender with brown hair and eyes, according to his registration card. The war would end in a couple of months, Armistice Day coming on 11 November 1918 and Jaque was not be drafted.

But he still joined the military, enlisting in April 1919 and serving as an engineer for three years—coming out in April 1922. I am not sure what prompted Jaque to join the service, nor what he did—beyond engineering. He was discharged in New York, which suggests that he at least saw some of the country, if not the world.

By the end of 1922, Jaque was back in Colorado, writing to “Inland Printer” from Trinidad, about 85 miles south of Pueblo. Apparently, he had seen an announcement for “Weird Tales" (the first issue would come out in 1923) and found something interesting about it—perhaps the contents, certainly the typography. He sent it to the magazine for critique. (“The Inland Printer” published a section each issue with its editors commenting on “specimens of printing” readers sent in.) The magazine noted the announcement was “neat and rather unusual,” while the envelope and letterhead were “excellent,” but sniffed “the magazine itself hardly merits the name [“The Unique Magazine”], but, perhaps, it will grow and improve with age.”

The next year, 1923, Russel was in California, and getting married. On 21 September 1923, he wed Elvira Myrtha Auld. She was 24 (Jaque 25) and from Chicago, Illinois. Her father, John, was born in Ireland to Scottish parents. By 1920, John was no longer with the family—the census listed his wife, Ida, as a widow, but there’s a death record for him, or someone with the same name and birth month, for 1961—and Ida lived with her family in Oakland, California—perhaps that was where Russel and Elvira first met (if they overlapped; it’s not clear), or perhaps it gave them common ground. It must have been a hard life for the Aulds: Ida had given birth to 7 children—a big family, like the Chamberlains—including two sets of twins! In 1920, according to the census, none of them had jobs—meaning no official jobs. Three of the children were 18 or older, and so may have done some work for pay.

Russel and Elvira lived in Pasadena at the time of their marriage; the witnesses were Elvira’s mother and brother, who also lived in Pasadena. That continued to be their home at the time of the 1930 census, and, as best can be judged from official documents, life continued to be challenging. Russel worked as a printer in a print shop; they rented their home—$30 per month—and had two children and one of Elvira’s sisters living with them. They also had a live-in servant, a widower, but no radio in the house. Unusual for a married woman at the time, Elvira worked outside the home, as a bookkeeper for a newspaper. And Gladys, her sister, was a real estate advertiser.

In June, Russel was admitted to a home for disabled veterans in Sawtelle, California. He suffered from chronic bronchitis and neurasthenia. The chronic bronchitis might very well have been a aide effect of working in the printing industry, which exposed laborers to a stew of noxious chemicals. Neurasthenia was a once common diagnosis that is no longer recognized. It was associated, especially, with inability to cope with the rapidity of modern life—think of nervous breakdowns—and after World War I, with the effects of extreme stress on the human body. Jaque’s neurasthenia could have been a case of what we now call PTSD, or a response to the strain of work and family life. Or something else altogether, of course.

In 1934, still living in Pasadena, Jaque published the first of his books—at least of those I know about. I have not seen it, nor have I seen any of his other writing. It is incredibly obscure. His early work seems to have been self-published, and the only copies I have discovered are at the University of California, Santa Barbara’s special collections; later works have a different publisher, but are similarly rare, at UCSB or the New York Public Library’s special collections. There’s also a piece in a small publication from the 1970s. The titles are enough to suggest the drift of his thought, and that there is an interesting line of thought ere which bears closer scrutiny—by someone—but it goes beyond the bounds of Forteanism, especially considering Jaque only has a short period of documented connection with the Society.

The book was titled “Facemarks” and, in part, the subtitle was “method of instantaneous reading of the colors, contours and expressions of the faces of mankind.” Purportedly, it contained a plan of study. Judging by the title, the book stood in the tradition of physiognomy, a 19th-century fringe science; whether it was an update or retread, I obviously don’t know.

Six years later, Jaque put out another book on what would have been fringe topic for the time. It was called “The Peace Book” and, according to the subtitle, offered “practical technique for achieving absolute non-violence.” Jaque aimed his work at “pacifists, conscientious objectors, humanists, and all peace workers of the world.” It was a slim volume, put out by “Advance Book Service,” running only 32 pages. (The subtitle called to a “pocket guide). As far as I can determine, “advance book service” put out no other volumes, which suggests it was Jaque’s own press. And like the first book, it seems that the book was a compilation of what others wrote, edited by Jaque, rather thann something he composed.

The year “The Peace Book” came out, the census captured the Jaques living in Los Angeles, at 956 Glen Arbor Avenue. They were renting a house—still at $30 per. Russel hadn’t worked in two years and was seeking work. Elvira was the one keeping the family afloat, it seems, making $1,200 per year as a bookkeeper for a wholesale drug company. (She had worked all 52 weeks the previous year, 40 hours each week.) Their two sons were at school, one in 7th grade, the other a sophomore in high school. No one else lived in the house.

Whether or not physiognomy was an idle curiosity or something more, I don’t know—but pacifism and its cultural attendants were clearly dear to Jaque’s heart. There’s an index to correspondence and case files of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, and Jaque appears in it. According to the summary, on 11 July 1940, Jaque “renounced nationalistic obligations of cit[i]z[enshi]p.” This was the day after the beginning of the Battle of Britain, but I do not know if that was the precipitating cause, or something else. Then, after America entered the War—in December 1941—he started to wonder that this meant for his own participation in the effort—and his own status. on 6 January 1942, he wrote the INS asking what international laws applied to him, what his status in America was—as a non-alien and non-national, and whether he had to register for the draft.

I have not seen the INS’s answer, if there was one, but the request, together with Jaque’s renunciation, makes clear that he had come far in two decades. It may be that what he saw during his service in the early 1920s was what radicalized him, or it may not be, I don’t know, but he was a committed pacifist now, and joined the ranks of those like Garry Davis and Caresse Crosby; Jaque was pushing toward some kind of global citizenship—and rejecting war.

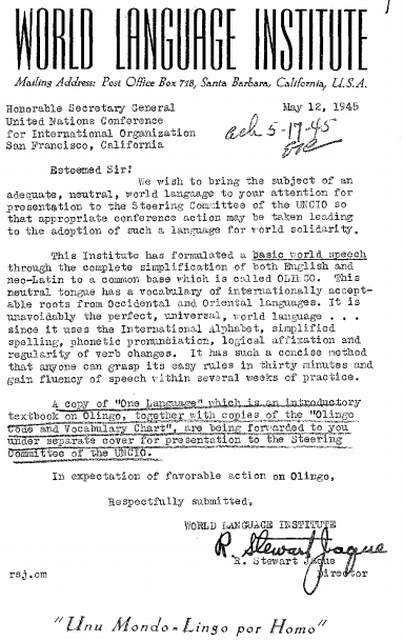

Jaque’s concern for pacifism (and possible interest in citizenship beyond national boundaries) seems to have been (one of) the root(s) from which his next project grew. In 1944, he published “One Language” (which was put out by the Santa Barbara publisher of fringe and metaphysical books J. Rowny Press). It was Jaque’s attempt to revise and update Esperanto, with a language he called Olingo. It was only 64 pages—Jaque did not write long books, apparently—but prided itself on taking a lot of words from non-European languages. It also removed accented letters. The book received a modicum of attention—infinitely more than his earlier works, infinitely less than Esperanto itself.

He continued to publish books in the late- and immediate post- War years. Again, I have not seen them—again, the only extant copies I kind find are at the University of California, Santa Barbara Special Collections (and, in the latter case, the New York Public Library). In 1945 he put out “The Gloriyat,” which was published by the “Gift Book Club” in Riverside. The library catalog entry for the book has it at 46 pages, including an index, and lists it both as a bibliography and as on “meditations.” The following you Rowny published for him “The Christmas Ghost and Other Writings,” a 29-page booklet catalogued as concerning “Christianity—Controversial Literature” and “Free Thought.” That year’s city directory, by the way, has Jaque living in Santa Barbara and employed as a writer.

Information on his activities is harder to come by from the 1950s on. In 1950, he revised his Olingo with the mystical writer George Arnsby Jones. The updated language was called “Globaqo”: the “brotherhood tongue for world freefolk economy.” As with his earlier attempt at a universal language, Globaqo received a smattering attention, as in a 1955 notice in the “International Language Review” (and advertisements for it appeared as late as 1968.) That Jones was a co-author and Rowny a publisher does not seem to have been happenstance. Apparently, Jaque was becoming increasingly attached to New Age spirituality—remember that Santa Barbara was a center of American Theosophy and some of its off-shoots.

Some time during this decade, Jaque traveled to India, to meet Kripal Singh, founder of Ruhani Satsang (School of Spirituality or Science of the Soul). Singh became a world-renowned guru, a syncretic religion. Jaque wrote about Singh and the six-months he spent at his Ashram in 1959’s “Gurudev: The Lord of Compassion.” The book was apparently reprinted in 1977, and it is that edition which is housed at UCSB. There are two volumes, one of text and one of prints. An excerpt of the book may also have appeared in a small magazine called “Morning Talks” in 1972.

Russell Stewart Jaque’s last known address was in San Francisco. He died 11 June 1990, five days after he had turned 92.

****************

Given the dearth of detailed information, I do not know Jaque’s path to Forteanism or his interpretation of the subject, but, if this were a novel, his coming to the Society would have been overdetermined. He practiced a profession Tiffany Thayer idolized—based on his reading of the early Fortean Harry Leon Wilson: Wilson had called printing a “good loose trade,” and Thayer concurred. It was a portable skill, allowing one to travel freely and do as one pleased without being tied down. He developed into a pacifist and had mystical inclinations; he was a pamphleteer, and Thayer collected pamphleteers. He resisted the determinisms of the state. Jaque must have been an eclectic reader, and investigating any of his enthusiasms could have uncovered mention of the Fortean Society.

So the only surprise is that he did not appear in the Society’s publication, Doubt, until 1952, and then only that one year. The mentions are in Doubt 35 (January 1952) and 36 (April 1952). Both mentions only deepen what we already know about him from the above sketch: that he was skeptical of government interventions, a left libertarian, as was common among the Forteans, opposed to mandatory medical requirements. Thayer made the Society a clearinghouse for opposition to vaccinations and fluoridation of water, and Jaque agreed with him on these points.

The first inclusion of Jaque in Doubt was the publication of two letters that he had written. The first was dated 10 October 1951; the recipient was unknown, but it seems to have been a form letter of some sort, sent out to many people. It started out by citing the authority of the U.S. Constitution as a bulwark against mandatory medical interventions. It then set out its argument, in a paragraph that presages much contemporary argument against vaccinations: that the germ theory isn’t correct, that individuals should have control over their body, that the medical professions has been bought off by the pharmaceutical industry.

“If freemen still roam the broad expanse of this country, free from compulsion or restraint, if justice still blossoms in the communal activities of the American people, if commercially-minded medical exploitation does not influence, dictate to and control governmental agencies and services such as U.S. Public Health Service, if the nervous system, and not the erroneous germ theory, provides the basis upon which the cause of disease rests, what can I expect in this instance from the Universally Inherent Life force and Principle?”

Included with this letter was a separate one, to the U.S. Public Health Service, dated 8 days earlier. In it, he enumerated 7 points. Apparently, these stemmed from an incident that had occurred in September, as he traveled from Mexico to the United States. Public Health officials took him from a train to one of their offices because he had refused to accept a vaccination—he was “opposed to the pollution of the human bloodstream with pus-virus from diseased cattle.” They wanted him to sign a refusal form, but did not have one on their possession in the train; but then they would not allow him to sign one in the office, either, and he was forced to get the vaccine, even though he offered a blood test to prove he was disease free. Jaque saw this as an arbitrary exercise of power against his bodily integrity. He demanded recompense.

I am not sure of the outcome of his campaign, but he continued it, regardless. The next issue offered for sale one of his pamphlets—and for the first and only time referred to Jaque as a member of the Society. Thayer wrote,

“Another MFS who would let nature takes it course, not only in malaise but in most everything else, is R. Jaque, whose run-in with the stooges for serum-makers has been mentioned in recent DOUBTs. Jaque has compiled a mimeographed booklet called Freefolk Guide, ‘a nature-lover’s manuscript which tells you how you can free yourself from civilized slavery to markets, doctors, drug-stores and tax-collectors.’

“The chances are you won’t go the whole way with Frere Jaque, but you can’t read Freefolk Guide without some profit. From the Society, $1.00.”

The glimpse into this pamphlet, which I have not otherwise seen, gives more insight into Jaque’s position. He seems to be putting forth an anarchist position. If nothing else, it would explain why he is relatively difficult to track in the 1950s—and may go some distance to explaining why he did not remain tightly bound to the Society, After all, it was another organization. Unfortunately, the pamphlet is another of Jaque’s products which I cannot find.

By the end of 1922, Jaque was back in Colorado, writing to “Inland Printer” from Trinidad, about 85 miles south of Pueblo. Apparently, he had seen an announcement for “Weird Tales" (the first issue would come out in 1923) and found something interesting about it—perhaps the contents, certainly the typography. He sent it to the magazine for critique. (“The Inland Printer” published a section each issue with its editors commenting on “specimens of printing” readers sent in.) The magazine noted the announcement was “neat and rather unusual,” while the envelope and letterhead were “excellent,” but sniffed “the magazine itself hardly merits the name [“The Unique Magazine”], but, perhaps, it will grow and improve with age.”

The next year, 1923, Russel was in California, and getting married. On 21 September 1923, he wed Elvira Myrtha Auld. She was 24 (Jaque 25) and from Chicago, Illinois. Her father, John, was born in Ireland to Scottish parents. By 1920, John was no longer with the family—the census listed his wife, Ida, as a widow, but there’s a death record for him, or someone with the same name and birth month, for 1961—and Ida lived with her family in Oakland, California—perhaps that was where Russel and Elvira first met (if they overlapped; it’s not clear), or perhaps it gave them common ground. It must have been a hard life for the Aulds: Ida had given birth to 7 children—a big family, like the Chamberlains—including two sets of twins! In 1920, according to the census, none of them had jobs—meaning no official jobs. Three of the children were 18 or older, and so may have done some work for pay.

Russel and Elvira lived in Pasadena at the time of their marriage; the witnesses were Elvira’s mother and brother, who also lived in Pasadena. That continued to be their home at the time of the 1930 census, and, as best can be judged from official documents, life continued to be challenging. Russel worked as a printer in a print shop; they rented their home—$30 per month—and had two children and one of Elvira’s sisters living with them. They also had a live-in servant, a widower, but no radio in the house. Unusual for a married woman at the time, Elvira worked outside the home, as a bookkeeper for a newspaper. And Gladys, her sister, was a real estate advertiser.

In June, Russel was admitted to a home for disabled veterans in Sawtelle, California. He suffered from chronic bronchitis and neurasthenia. The chronic bronchitis might very well have been a aide effect of working in the printing industry, which exposed laborers to a stew of noxious chemicals. Neurasthenia was a once common diagnosis that is no longer recognized. It was associated, especially, with inability to cope with the rapidity of modern life—think of nervous breakdowns—and after World War I, with the effects of extreme stress on the human body. Jaque’s neurasthenia could have been a case of what we now call PTSD, or a response to the strain of work and family life. Or something else altogether, of course.

In 1934, still living in Pasadena, Jaque published the first of his books—at least of those I know about. I have not seen it, nor have I seen any of his other writing. It is incredibly obscure. His early work seems to have been self-published, and the only copies I have discovered are at the University of California, Santa Barbara’s special collections; later works have a different publisher, but are similarly rare, at UCSB or the New York Public Library’s special collections. There’s also a piece in a small publication from the 1970s. The titles are enough to suggest the drift of his thought, and that there is an interesting line of thought ere which bears closer scrutiny—by someone—but it goes beyond the bounds of Forteanism, especially considering Jaque only has a short period of documented connection with the Society.

The book was titled “Facemarks” and, in part, the subtitle was “method of instantaneous reading of the colors, contours and expressions of the faces of mankind.” Purportedly, it contained a plan of study. Judging by the title, the book stood in the tradition of physiognomy, a 19th-century fringe science; whether it was an update or retread, I obviously don’t know.

Six years later, Jaque put out another book on what would have been fringe topic for the time. It was called “The Peace Book” and, according to the subtitle, offered “practical technique for achieving absolute non-violence.” Jaque aimed his work at “pacifists, conscientious objectors, humanists, and all peace workers of the world.” It was a slim volume, put out by “Advance Book Service,” running only 32 pages. (The subtitle called to a “pocket guide). As far as I can determine, “advance book service” put out no other volumes, which suggests it was Jaque’s own press. And like the first book, it seems that the book was a compilation of what others wrote, edited by Jaque, rather thann something he composed.

The year “The Peace Book” came out, the census captured the Jaques living in Los Angeles, at 956 Glen Arbor Avenue. They were renting a house—still at $30 per. Russel hadn’t worked in two years and was seeking work. Elvira was the one keeping the family afloat, it seems, making $1,200 per year as a bookkeeper for a wholesale drug company. (She had worked all 52 weeks the previous year, 40 hours each week.) Their two sons were at school, one in 7th grade, the other a sophomore in high school. No one else lived in the house.

Whether or not physiognomy was an idle curiosity or something more, I don’t know—but pacifism and its cultural attendants were clearly dear to Jaque’s heart. There’s an index to correspondence and case files of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, and Jaque appears in it. According to the summary, on 11 July 1940, Jaque “renounced nationalistic obligations of cit[i]z[enshi]p.” This was the day after the beginning of the Battle of Britain, but I do not know if that was the precipitating cause, or something else. Then, after America entered the War—in December 1941—he started to wonder that this meant for his own participation in the effort—and his own status. on 6 January 1942, he wrote the INS asking what international laws applied to him, what his status in America was—as a non-alien and non-national, and whether he had to register for the draft.

I have not seen the INS’s answer, if there was one, but the request, together with Jaque’s renunciation, makes clear that he had come far in two decades. It may be that what he saw during his service in the early 1920s was what radicalized him, or it may not be, I don’t know, but he was a committed pacifist now, and joined the ranks of those like Garry Davis and Caresse Crosby; Jaque was pushing toward some kind of global citizenship—and rejecting war.

Jaque’s concern for pacifism (and possible interest in citizenship beyond national boundaries) seems to have been (one of) the root(s) from which his next project grew. In 1944, he published “One Language” (which was put out by the Santa Barbara publisher of fringe and metaphysical books J. Rowny Press). It was Jaque’s attempt to revise and update Esperanto, with a language he called Olingo. It was only 64 pages—Jaque did not write long books, apparently—but prided itself on taking a lot of words from non-European languages. It also removed accented letters. The book received a modicum of attention—infinitely more than his earlier works, infinitely less than Esperanto itself.

He continued to publish books in the late- and immediate post- War years. Again, I have not seen them—again, the only extant copies I kind find are at the University of California, Santa Barbara Special Collections (and, in the latter case, the New York Public Library). In 1945 he put out “The Gloriyat,” which was published by the “Gift Book Club” in Riverside. The library catalog entry for the book has it at 46 pages, including an index, and lists it both as a bibliography and as on “meditations.” The following you Rowny published for him “The Christmas Ghost and Other Writings,” a 29-page booklet catalogued as concerning “Christianity—Controversial Literature” and “Free Thought.” That year’s city directory, by the way, has Jaque living in Santa Barbara and employed as a writer.

Information on his activities is harder to come by from the 1950s on. In 1950, he revised his Olingo with the mystical writer George Arnsby Jones. The updated language was called “Globaqo”: the “brotherhood tongue for world freefolk economy.” As with his earlier attempt at a universal language, Globaqo received a smattering attention, as in a 1955 notice in the “International Language Review” (and advertisements for it appeared as late as 1968.) That Jones was a co-author and Rowny a publisher does not seem to have been happenstance. Apparently, Jaque was becoming increasingly attached to New Age spirituality—remember that Santa Barbara was a center of American Theosophy and some of its off-shoots.

Some time during this decade, Jaque traveled to India, to meet Kripal Singh, founder of Ruhani Satsang (School of Spirituality or Science of the Soul). Singh became a world-renowned guru, a syncretic religion. Jaque wrote about Singh and the six-months he spent at his Ashram in 1959’s “Gurudev: The Lord of Compassion.” The book was apparently reprinted in 1977, and it is that edition which is housed at UCSB. There are two volumes, one of text and one of prints. An excerpt of the book may also have appeared in a small magazine called “Morning Talks” in 1972.

Russell Stewart Jaque’s last known address was in San Francisco. He died 11 June 1990, five days after he had turned 92.

****************

Given the dearth of detailed information, I do not know Jaque’s path to Forteanism or his interpretation of the subject, but, if this were a novel, his coming to the Society would have been overdetermined. He practiced a profession Tiffany Thayer idolized—based on his reading of the early Fortean Harry Leon Wilson: Wilson had called printing a “good loose trade,” and Thayer concurred. It was a portable skill, allowing one to travel freely and do as one pleased without being tied down. He developed into a pacifist and had mystical inclinations; he was a pamphleteer, and Thayer collected pamphleteers. He resisted the determinisms of the state. Jaque must have been an eclectic reader, and investigating any of his enthusiasms could have uncovered mention of the Fortean Society.

So the only surprise is that he did not appear in the Society’s publication, Doubt, until 1952, and then only that one year. The mentions are in Doubt 35 (January 1952) and 36 (April 1952). Both mentions only deepen what we already know about him from the above sketch: that he was skeptical of government interventions, a left libertarian, as was common among the Forteans, opposed to mandatory medical requirements. Thayer made the Society a clearinghouse for opposition to vaccinations and fluoridation of water, and Jaque agreed with him on these points.

The first inclusion of Jaque in Doubt was the publication of two letters that he had written. The first was dated 10 October 1951; the recipient was unknown, but it seems to have been a form letter of some sort, sent out to many people. It started out by citing the authority of the U.S. Constitution as a bulwark against mandatory medical interventions. It then set out its argument, in a paragraph that presages much contemporary argument against vaccinations: that the germ theory isn’t correct, that individuals should have control over their body, that the medical professions has been bought off by the pharmaceutical industry.

“If freemen still roam the broad expanse of this country, free from compulsion or restraint, if justice still blossoms in the communal activities of the American people, if commercially-minded medical exploitation does not influence, dictate to and control governmental agencies and services such as U.S. Public Health Service, if the nervous system, and not the erroneous germ theory, provides the basis upon which the cause of disease rests, what can I expect in this instance from the Universally Inherent Life force and Principle?”

Included with this letter was a separate one, to the U.S. Public Health Service, dated 8 days earlier. In it, he enumerated 7 points. Apparently, these stemmed from an incident that had occurred in September, as he traveled from Mexico to the United States. Public Health officials took him from a train to one of their offices because he had refused to accept a vaccination—he was “opposed to the pollution of the human bloodstream with pus-virus from diseased cattle.” They wanted him to sign a refusal form, but did not have one on their possession in the train; but then they would not allow him to sign one in the office, either, and he was forced to get the vaccine, even though he offered a blood test to prove he was disease free. Jaque saw this as an arbitrary exercise of power against his bodily integrity. He demanded recompense.

I am not sure of the outcome of his campaign, but he continued it, regardless. The next issue offered for sale one of his pamphlets—and for the first and only time referred to Jaque as a member of the Society. Thayer wrote,

“Another MFS who would let nature takes it course, not only in malaise but in most everything else, is R. Jaque, whose run-in with the stooges for serum-makers has been mentioned in recent DOUBTs. Jaque has compiled a mimeographed booklet called Freefolk Guide, ‘a nature-lover’s manuscript which tells you how you can free yourself from civilized slavery to markets, doctors, drug-stores and tax-collectors.’

“The chances are you won’t go the whole way with Frere Jaque, but you can’t read Freefolk Guide without some profit. From the Society, $1.00.”

The glimpse into this pamphlet, which I have not otherwise seen, gives more insight into Jaque’s position. He seems to be putting forth an anarchist position. If nothing else, it would explain why he is relatively difficult to track in the 1950s—and may go some distance to explaining why he did not remain tightly bound to the Society, After all, it was another organization. Unfortunately, the pamphlet is another of Jaque’s products which I cannot find.