A moonstruck Fortean.

This one's huge. Be forewarned.

Robert Lee Farnsworth was born 3 July 1909 in Illinois—which puts him of the same generation and same background as Tiffany Thayer, midwestern men born a little too late to serve in the Great War. His father, Lee—seemingly the inspiration for Robert’s middle name; I have no reason to suspect it was a reference to the Civil War general—was a real estate broker. His mother’s name was May D., but at least one record has her as Mattie, apparently a slurring together of the fist name and middle initial. She had been born in New Jersey. Lee was 34, and May about 27 when Robert was born. He was an only child—although not by choice.

Check the 1930 census, and Lee Orville gives his age at first marriage as 30. Check the newspapers, and the story is different. He was the son of a wealthy widow, and had attended law school at Northwestern, where he was a promising student. While there, he secretly married Maude Seaton in Milwaukee. That was in 1896, a full decade before he’d marry May. The wedding did not go as planned. In 1902, Maude told a judge, "Our marriage was an elopement. We agreed to keep it secret. In living up to this agreement, I think my husband overdid the thing. He kept the matter secret even from me.” Farnsworth left Maud the day of their wedding; years later, she successfully sued to get her maiden name back.

This one's huge. Be forewarned.

Robert Lee Farnsworth was born 3 July 1909 in Illinois—which puts him of the same generation and same background as Tiffany Thayer, midwestern men born a little too late to serve in the Great War. His father, Lee—seemingly the inspiration for Robert’s middle name; I have no reason to suspect it was a reference to the Civil War general—was a real estate broker. His mother’s name was May D., but at least one record has her as Mattie, apparently a slurring together of the fist name and middle initial. She had been born in New Jersey. Lee was 34, and May about 27 when Robert was born. He was an only child—although not by choice.

Check the 1930 census, and Lee Orville gives his age at first marriage as 30. Check the newspapers, and the story is different. He was the son of a wealthy widow, and had attended law school at Northwestern, where he was a promising student. While there, he secretly married Maude Seaton in Milwaukee. That was in 1896, a full decade before he’d marry May. The wedding did not go as planned. In 1902, Maude told a judge, "Our marriage was an elopement. We agreed to keep it secret. In living up to this agreement, I think my husband overdid the thing. He kept the matter secret even from me.” Farnsworth left Maud the day of their wedding; years later, she successfully sued to get her maiden name back.

That episode in the past, the family settled in Glen Ellyn, a tiny village—population less than 800 in 1910—located in Chicago’s suburbs. Familial drama, though, was not over. In 1914, the Farnsworths attempted to adopt Victor, a five year old boy like Robert. The adoption, though, was messy: Victor was initially in the care of another attorney, Frank Comerford, and his wife Jean. They had taken him in after he had moved through a couple of other households, having been put with those families when his mother contracted tuberculosis. The mother had signed a document which, she said later, she thought only gave the Comerfords temporary custody, but which actually gave them complete control over the child. (Victor’s father never signed a document.) The mother and father lost track of Victor after he had left the Comerford’s care, and hired a detective to find him, which they did, and eventually nullified the adoption.

The teens continued to be a disruptive time for the Farnsworths, eventually giving way to a more prosperous decade. Lee signed up for alternative service during the Great War—he was in his forties—acting as a secretary of the National War Work Council of the YMCA and worked with American Expeditionary Forces in France. He left the family in May 1918 and did not return March 1919. The 1920 census had him back in Glen Ellyn, working in real estate. The family had taken out a mortgage on a home, which suggests its economic fortunes were improving. There was rapid growth during Farnsworth’s lifetime, the village population increasing ten times by 1930. Lee was at the center of much of this development, responsible for several large subdivisions and important buildings, even as competition in the real estate business increased; he also was an underwriter. In 1923, Lee—alone, apparently—traveled again to France (and England and Belgium), for pleasure. During this time, presumably, Robert attended to his studies in public school.

If the family’s financial status can be judged by their home, then it had declined by 1930, when the Farnsworth’s were renting a house for $75. Lee was still in real estate; Robert, having finished high school, did clerical work. I do not know what happened with the family through the rest of the 1930s, although it appears—from an absence of evidence, admittedly—that Lee was less active, or at least less successful than he had been in the 1920s. Given the turn in the national economy, the family’s (possible) decline is not a surprise.

By 1940, Robert had struck out on his own. That year, on 8 November, he married Evelyn Swenson in Chicago. She was the daughter of a Norwegian immigrant who worked on the Chicago police force, and an Illinois woman. Evelyn was a few years older—born 28 June 1904—and worked as a stenographer, at least in 1930. The records suggest that Robert had moved into Chicago sometime during the 1930s, and that was where the couple met. Evelyn was the eldest of five siblings. I can find no other records of Robert and Evelyn for the early 1940s—no census record, no military registration.

Lee Farnsworth appears again in the early 1940s, now as a justice. Glen Ellyn was much larger than when the Farnsworth’s had first arrived, but Lee was still an important man, and involved in political wrangling, running for office in 1943 as part of an upstart political party. He would die two years later; I don’t know what happened to May Farnsworth. Meanwhile, his son was looking for a frontier even vaster than the transformation of a small village into a populous suburb.

Robert worked for a rubber company in the 1940s, according to newspaper accounts—likely Goodyear—but his career was something else: he wanted to guide U.S. space policy—to prompt a rocket to the moon, and the beginning of a new empire. He seems to have been familiar with science fiction, but his main interest, at least initially, was to turn fiction into fact, to make those galactic empires of the pulps into reality. In 1942, he founded the United States Rocket Society. It got a slow start—the society was part of Farnsworth’s signature in a letter he sent to Astounding that year, and there were advertisements in Popular Science—but otherwise the first couple of years were quiet: “Join U. S. Rocket Society! Information, dime. 4108-501 N. Kenmore, Chicago.”

The mid-1940s saw changes in Farnsworth's life, and an explosion of activity by his Society. At some point, he became office manager for Pennsylvania Oil in Chicago. Evelyn and he had two children, a son (Robert) in 1944, and a daughter (Tannissee) around 1947. And Farnsworth learned how to use the press to bring attention to his cause: the world itself seemed to be making science fiction into science fact, and the ‘rocket zanies’ no longer seemed so zany. Launching rockets in the desert, writing cryptic pamphlets no longer seemed the limit. Rockets, like other technological developments, heralded a new development in civilization. And the U.S. Rocket Society was the true prophet of their coming. The 1940s saw a number of amateur and semi-professional rocket societies, including one in Chicago—the Chicago Rocket Society, founded in 1946—but Farnsworth had little to nothing to do with these organizations, attempting, instead, to make his the de facto voice of American rocketry.

The first indication of the more prominent (if not renewed) activity came in December 1944. If one thought of the moon as real estate—who owned it? And how could someone buy property? The question was once pie in the sky—ha!—but with the development of rocket technology, Farnsworth thought, the question was pressing. And so he wrote to the Department of the Interior, wondering if there were rules. The Department noted that homesteading the moon would be controlled by the General Land Office, and the 5,000 (!!) public land laws it administered. That meant anyone wanting testate a claim on the moon had to submit an affidavit of interest and establish a permanent residence on that site within six months of approval. The story of the unusual correspondence was picked up by the Associated Press, and spread over the newswires.

The next month—January 1945—saw Farnsworth hitting his stride. He told newspapers the technology was no longer the problem—the only reasons humans stayed earthbound was financing. And this was a big risk, not shooting for the moon. The Germans might get there first, and drop bombs from the high heavens—or even, as precision increased, from Europe. If, on the contrary, Americans perfected rockets first, and reached the moon, it would be a boon for businesses: humans could settle there, living in specially made rockets while they constructed buildings on the surface. The moon, he said, was a perfect observatory, an excellent vantage for mapping the earth, a laboratory for viewing the weather, and—most importantly—the key way station for interplanetary travel.

By this point, Farnsworth claimed membership in his Society numbered 4,000, four-fifths of whom were in the military. He sent them regular updates, but in 1945 upgraded his publications—the first issue of Rockets appeared in May 1945. Startling Stories, the science fiction, was not impressed with the first issue—nor its price—a truly startling $1 per issue, for what was a relatively small quarterly—it measured about ten pages. Later issues, though, were more professional, and Startling Stories’s reviewer called it excellent, and admitted he had changed his mind. Rockets seems to have inspired Farnsworth to reissue a pamphlet he had written—Rockets, New Trail to Empire.

Farnsworth had originally published the pamphlet in July 1943, but it doesn’t seem to have received any publicity. With his name now in the papers, the piece caught some attention. Trail to Empire expanded the argument he had been making the past several months. It started with a basic description of rockets and their possible uses: carrying mail, carrying passengers, studying the weather, and then dealt with the various technical issues still plaguing rocket engineering: reaching escape velocity, financing their building, discovering the right kind of fuel, design, and how to make certain the rockets could return. He then argued that rockets should be aimed at the moon, as a business opportunity, and as the seed of a new empire. He predicted colonization of the moon would prompt a new Renaissance, as every possible subject from art to economics would be revitalized—with new forms made possible by weightlessness and new opportunities created. [http://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.$b80383;view=1up;seq=9]

Days after the end of World War II, Farnsworth was back in the news. He petitioned the U.S. government for permission to use atomic power in peaceful pursuits: the energy that had destroyed two Japanese cities could be harnessed for space travel. Atomic power could life rockets beyond earth’s gravitation, and could heat astronauts wherever they landed. Farnsworth figured that, with atomic power, the entire galaxy could be visited easily. The moon would still play a key role—it would be the “Chicago of the solar universe,” the place where trade routs intersected. This particular story was carried by the United Press, but variations on it, expressing the constellation of Farnsworth’s concerns, would echo through the press for a couple of years. He appeared on the television special “Exploring the Unknown” in December 1945; when the Army claimed to have bounced radar off the moon, he told newspapers the feat only proved his theories; he predicted that with proper financing the moon could be reached before the 1950s. Interest in the Society was high enough that in 1946, he started charging a quarter to those who read the ad in Popular Science and were inclined to write him for more information.

Farnsworth’s proclamation of a new manifest destiny had varying success among science fiction fans. Startling Stories continued to recommend Rockets through the 1940s, and even opened its pages to Farnsworth. He published “First Target in Space” in the September 1948 issue and “Rocket Target No. 2” in May 1949. The first reiterated, once again, Farnsworth’s idea that Americans should claim the moon. He does take the argument in a different direction, though, contradicting those who thought the moon a ‘dead planet,’ suggesting that there might be volcanic activity, even living beings. (Fellow Fortean Eric Frank Russell was among those who thought a trip to the moon worthless.) I have not seen “Rocket Target No. 2.” He seems also to have contributed to the ‘zine “Alien Culture” in April 1949.

Farnsworth also found a warm reception among Midwestern fans. He became close with Donn Brazier, who published the ‘zine “Embers.” Brazier recommended Rockets no later than the fourth issue, and had Farnsworth on his priority mailing list. The ‘zine ran ads for the U.S. Rocket Society, and included articles in dialogue with those in Rockets. Always publicity-conscious, Farnsworth sent Ember an autographed photograph. Later, the two met, and Ember came away convinced that Farnsworth had solid government contacts.

When Startling Stories first noticed Rockets, the reviewer thought it would be good only for rocket fanatics. Shortly thereafter, Farnsworth incorporated science fiction, and SF fans noticed. British fan Walter Gillings wrote in his Fantasy Review, “Unlike most astronautics journals, Rockets, organ of the U.S. Rocket Society, has sympathetic interest in science fiction, is considering featuring it. Fan magazines get reviews in its columns; it even deals in rumors for which fandom is notorious. Suggests that Raymond A. Palmer, Amazing Stories editor, writes the Richard Shaver ‘Lemurian Hoax’ tales aforementioned; that Editor Campbell, too, does the pieces in Astounding under the name of George O. Smith. Comments: ‘It may explain monotonous sameness of the science fiction digest. Thank Heaven for Van Vogt!’”

Not all the fans, however, were as content with this drift. The fan historian Harry Warner wrote in his All Our Yesterdays, “The rocket group that made the biggest splash in America’s fandom during this decade [the 1940s] was the non-fannish United States Rocket Society. It worked out a deal with me at the start of 1942 that provided it with a page in my fanzine Spaceways for publication of its news. In return, I got an imposing number of new customers: everyone on its membership roster. R. L. Farnsworth, Chicago, was the president. By 1946 it had its own lithographed 16-page publication called Rockets, but the science had become adulterated with mysticism and Forteanism.” In the early 1950s, Startling Stories had switched reviewers of ‘zines, and the new writer was not pleased with Farnsworth’s publication: Rocket's material is definitely of value to those interested in rockets—and who isn't?—but our careful calculations indicate that the ‘zine costs one buck per copy, which seems on the walloping side for seven, pages’ mimeographed~on one side. Included in this -issue are reports on rocket-doings, a plethora of bombastic bleats such as NEW HORIZONS! GET READY! FOR THE CONQUEST OF SPACE! Altogether we found ROCKETS interesting, fairly newsy, and inclined to gurgle in its enthusiasm.”

The matter which most struck in the craw of fans was Farnsworth’s unapologetic imperialism. British writers were especially sensitive to his patriotism. The British Interplanetary Society had been established in 1933 by P. E. Cleator to advocate for space exploration—and its members were anguished by the idea of Americans taking the lead, and doing so for business and country, which stood against the scientific ideal of selflessly sharing knowledge beyond national borders. Arthur C. Clarke, one of the earliest members of the BIS, penned a bitter attack on Farnsworth’s pamphlet, bemoaning his jingoism and water-carrying for American businesses. He feared Farnsworth’s use of “all the most blatant tricks of journalistic advertising” would turn astronautics into a “laughingstock.” Cleator also went after Farnsworth in the Journal of the British Interplanetary Society. Farnsworth replied in the Journal, urging them to get over their differences so that they could focus on getting a rocket to space, but Cleator was not mollified, complaining to H. L. Mencken about him.

In 1952, the author Marion Zimmer Bradley also criticized Farnsworth. He critique came in the pages of Startling Stories and took issue with his underlying assumption: that humankind needed to reach the stars to survive. It was exactly the constant search for new frontiers to conquer that kept humanity in its infancy. Rather than confront problems, people—read: men—lit out for the colonies, the West, anywhere. In the process, they created new problems—the extinction of bison and Native Americans, the creation of a society marred and marked by violence—without solving older ones. Indeed, she suggested, those most likely to head for the frontiers were those incapable of fitting into nora society. So save space exploration for some other time, after humans had stewed in their juices and solved the very many problems that plagued the species. (The editor of Startling Stories argued in return that the desire to see new places and confront new challenges was one of humanity’s great gifts.) Bradley was a woman, and therefore something of an outsider, and she did not like Farnsworth’s championing of the mainstream, the perpetuation of the current cultural order: a cultural order, not incidentally, which had almost destroyed civilization twice in the previous thirty years.

Farnsworth continued on despite the protests against his vision, although the 1940s were to be the high point of his rocket career, at least in terms of the publicity he received. In 1950 and again in 1952 he ran for Congress, but lost badly in the primary to the incumbent Republican Chauncey W. Reed. Rockets continued into the late 1950s, still advertised in Popular Science; however, its price had come down—$1.00 per year for those under 18, $3.00 for those older. By that point, Farnsworth had relocated to Nevada, reaching that state in 1955. He worked as a real estate appraiser and was president of the Tennessee Uranium Mining Company. At some point—maybe in Nevada, maybe while he was still in Illinois—Farnsworth joined the Masons and the Shriners. Evelyn died in 1970. Robert died 3 August 1998, exactly one month after his 89th birthday.

As the commentary by those who knew him and read his Rockets shows, Farnsworth was inspired by Fort, and the Fortean Society. He seems to have known of Fort before he was mentioned in the Fortean Society. In 1945, Henry Holt noted, with amusement, that the U.S. Rocket Society had purchased several copies of Fort’s omnibus: “The United States Rocket Society ordered a quantity of Charles Fort's works—and it's a pity Mr. Fort can't know and relish that fact.” Likely, Farnsworth ordered the books in light of their reprint, but he also may have decided to do so since it was in 1945 that his Society was really taking off. He might have had reason to believe that he would need to share the the books a lot.

His name first appeared in Doubt 14 (Spring 1946), a few months after Holt’s comments—and Thayer (not for the only time) had a very different idea about the Society than his publisher. He saw no paradox with rocketeers buying the books of a man who claimed that the planets were nearby:

“When we were founding the Fortean Society, Charles Fort refused to join. We wanted to name him Honorary President, or to give him some other title, one especially calculated to remove all onus of vanity or self-exploitation, of which he had an insuperable dread. ‘No,’ said he, ‘call it the Interplanetary Exploration Society and I’ll come in, but not as long as it has my name on it.’

“Ever since, we have had the warmest cordiality for the rocketeers, and kept tabs on their progress here and abroad until censorship interfered.

“Now we are delighted to announce that the President of the United States Rocket Society, the well known pioneer in this field, R. L. Farnsworth, and one of the vice-presidents, John M. Griggs are members of the Fortean Society, and will thenceforward be our liaison—transportation-wise—with Luna, Mars, and points up.”

That same summer, Farnsworth’s Rockets advertised the Fortean Society—“The last stronghold of realistic, analytical thought.” And he provided an updated address. US Rocket Society members had been getting their letters returned when they used the address that he provided in the second edition of “Trails to Empire.” (He also recommended subscribing to the British Interplanetary Society, which had recently begun publishing again with the end of the war.)

Life Between Holt’s view and Thayer’s was tenuous though: was the US Rocket Society meant as a serious provocateur for space exploration, or a nose-thumbing joke at the scientific establishment? It wasn’t always clear, much to the chagrin of both the Forteans and their detractors among the science fiction and aeronautics communities.

On the Fortean side, Farnsworth kept Thayer well-supplied with clippings until the mid 1950s (ewhen he relocated to Nevada) many of them far afield of rocketry, and some expressing unexpected political perspectives. His name first appeared in Doubt, actually, a page before Thayer’s comments, appended to a series of clippings about mysterious creatures—what we’d now call cryptozoological reports. He also sent in material about mysterious balls of fire and dead fish washed ashore by the tons (Doubt 15); flying saucers (Doubt 19); a baby strangled to death in sleep by her necklace (Doubt 20); and a pamphlet that was sent home from school with Farnsworth’s son (Doubt 39):

“The 8-year-old son of Rocketeer Farnsworth brought home from school (Glen Ellyn, Ill.) a 16-page ‘comic’ book entitled FIRE AND BLAST! It had been given him by his teacher. It had been published by the National Fire Protection Association of Boston, and in it is reference to a previous publication, AMERICA IN FLAMES.

“The contents is [sic] unspeakably nefarious, an effort to terrify under the do-good cloak of teaching fire prevention. No school teacher fit for her post would put this obscene matter into a child’s hands, but the trick is turned by glorifying Civil Defense in the text.

“SPEAK UP in your Parent-Teacher meeting before this happens to your child. Oppose this ghastly attack upon juvenile mentality before the youngsters are subjected to it.”

Despite his plumping for America and big business, Farnsworth, apparently, also had a libertarian streak like Thayer’s: his must’ve just run in a more rightward direction. And all of these contributions are independent of other times that Farnsworth, and his ambitions, were referenced in Doubt. In addition, Farnsworth joined the third Chapter of the Fortean Society—the Chicago Chapter—during the late 1940s, when Thayer was playing with the idea of having local branches of the Society.

On the aeronautics side, Farnsworth’s peers—mostly in the scientific community—acknowledged that he was technically accurate in his discussion of rockets. Even his critic Clarke acknowledged his proficiency (minus a few howlers). His work was taken seriously enough to attract the attention of professional astronomer (and science fiction writer) R. S. Richardson, who found some of Farnsworth’s calculations shaky. When he stuck to the physics of rockets, and kept his Fortean musings hidden away in Doubt, he found respect.

The trouble was, for Farnsworth, Forteanism and rocketry were not separate subjects, but worked in conjunction with one another: the line between science fiction and science fact was too blurred. In a 1947 editorial for Rockets that was picked up by the United Press, Farnsworth surmised that the moon’s craters were left-over from a prehistoric atomic war between aliens. And perhaps those Lunarians came to earth, after that war, and were somehow involved with now-lost continents, such as Atlantis. A trip to the moon, the editorial said, could solve these ancient mysteries. Around the same time, attention was drawn to flying saucers, and Farnsworth chimed in. Don’t shoot! The discs could be electronic eyes from Mars. Or perhaps they were living creatures from Venus. The planet could have evolved a form of life that powered itself through the cosmos with electric current. Farnsworth made clear that these were Fortean musings, noting the large collection of reports Fort had gathered in his books about unusual lights in the sky.

(Incidentally, Farnsworth thus helped promote Fort back into the limelight with the flying saucer flap of the late 1940s. Among those to pick up on his musings was the Chicago journalist Marcia Winn, who became a Fortean and wrote approvingly of the Society in her columns.)

Although I have not read through the entire run of Rockets—it is rare—the consensus from others is that overtime it increasingly included bits of Forteana. A 1946 issue, for instance, included a column called “Fortean Data,” which discussed a weird star; and the books of Charles Fort were listed on the recommended reading. R. DeWitt Miller, a Fortean of good standing, used some of Farnsworth’s material in his Forgotten Mysteries. For science fiction fans who thought of Fort mostly as a stimulant to the imagination, and not at all a serious astronomical thinker, Farnsworth’s blending of the two subjects wrankled. A reviewer for Startling Stories poked fun at Rocket’s attraction to fringe science. Farnsworth’s rag had covered Velikovsky’s Worlds in Collision and decided, ‘This book is good fun and we understand that it is being made into a movie.’ The reviewer snarked back, ‘With Don Ameche as Venus?’ The whole point was to separate rocketry from crankery, to make it a real science, and Farnsworth was hurting the cause.

Thayer, on the contrary, thought Farnsworth to conventional, although admitted his was a necessary tactic. When news broke that radar had bounced off the moon, Thayer wrote in Doubt (14): “Probably he will report upon the recent ‘radar high jinks in the columns of his publication. No advocate of flights to Luna could afford to scorn such an opportunity. For what it may be worth, however, we pass along the observation of MFS Stevens, that such nonsense as the ‘Heaviside layer’ and other ‘ceilings’, which have been ‘bouncing back radio waves’ for ever so long, must have parted like the Red Sea to let ‘radar’ through—round trip!” Farnsworth was “moon-ho”; he had his cause—and the money spent would take away from war, anyway, even if it was all a boondoggle, and the planets, as Fort said, could be reached in short order.

But Thayer had his limits (and he tended to turn on allies, anyway), which Farnsworth crossed. In Doubt 17, Thayer wrote, that there was a “natural affinity of Forteans for the exploratory accounts for the closeness of our association with such institutions as the National Speleological Society and the United States Rocket Society.” But Forteans did not have to agree with those organization, and Thayer took exception to Farnsworth’s call to use atomic power in rockets headed to the moon. Farnsworth had made the comments in the press, in an American Weekly article had had written called “The Moon my Destination,” and in a letter to Senator Wayland C. Brooks. “We wish that this compromise with the Great Atom Fraud were not necessary, but if Farnsworth wants $350,000 to build his rocket he must assassinate his conscience to get it.” Other Forteans had their limits, too, and Buffalo’s B. Goldstein asked about the planned interplanetary empire: ‘Did it ever occur to Mr. F., that someone else may be there already?” For a Fortean Society that was all in with Native American rights, the prospect of a new empire, a new wild west, as Marion Zimmer Bradley had it, was awful. Thayer didn't want to be a part of it.

All of which raises the question, How did Farnsworth reconcile these two views, his acceptance of rocketry’s technical standards with a Fortean contempt for consensual reality? It is not clear from the writing I have studied how he managed to pull this off. But it is also worth noting that he was not the only person who worked at the blurry edge of conventional science and the paranormal. Ray Palmer made a career of it. There were others in Farnsworth’s orbit—Brazier, Griggs—who also sought to combine science and Forteanism. I guess one way to look at it is to say, that these men saw science (and engineering) developing so quickly that they were inclined to allow entirely imaginary parameters for the future. If rocketry had gone from a derided, amateurish hobby in the 1920s to an area of active scientific research in the 1940s—and it had—then who was to say what the final limits were? Why not electric fish flying through the cosmos. Nelson Bond had written a brilliant Fortean short story on just such a topic.

What surprises, then, even if we cannot completely come to terms with how Farnsworth combined these two sets of ideas that other people saw as diametrically opposed, is that the future world he imagined—the world of a science unconstrained by then-current limits, a world of atomic-powered rockets and terraforming and interplanetary trade and a renaissance of art and religion was encysted in such a conventional structure. All that imaginative power, and Farnsworth came up with a reworking of America’s myth of the frontier, manifest destiny, and financial imperialism. As much as the unsavory implications of Farnsworth’s project, the lack of imagination disappoints.

The teens continued to be a disruptive time for the Farnsworths, eventually giving way to a more prosperous decade. Lee signed up for alternative service during the Great War—he was in his forties—acting as a secretary of the National War Work Council of the YMCA and worked with American Expeditionary Forces in France. He left the family in May 1918 and did not return March 1919. The 1920 census had him back in Glen Ellyn, working in real estate. The family had taken out a mortgage on a home, which suggests its economic fortunes were improving. There was rapid growth during Farnsworth’s lifetime, the village population increasing ten times by 1930. Lee was at the center of much of this development, responsible for several large subdivisions and important buildings, even as competition in the real estate business increased; he also was an underwriter. In 1923, Lee—alone, apparently—traveled again to France (and England and Belgium), for pleasure. During this time, presumably, Robert attended to his studies in public school.

If the family’s financial status can be judged by their home, then it had declined by 1930, when the Farnsworth’s were renting a house for $75. Lee was still in real estate; Robert, having finished high school, did clerical work. I do not know what happened with the family through the rest of the 1930s, although it appears—from an absence of evidence, admittedly—that Lee was less active, or at least less successful than he had been in the 1920s. Given the turn in the national economy, the family’s (possible) decline is not a surprise.

By 1940, Robert had struck out on his own. That year, on 8 November, he married Evelyn Swenson in Chicago. She was the daughter of a Norwegian immigrant who worked on the Chicago police force, and an Illinois woman. Evelyn was a few years older—born 28 June 1904—and worked as a stenographer, at least in 1930. The records suggest that Robert had moved into Chicago sometime during the 1930s, and that was where the couple met. Evelyn was the eldest of five siblings. I can find no other records of Robert and Evelyn for the early 1940s—no census record, no military registration.

Lee Farnsworth appears again in the early 1940s, now as a justice. Glen Ellyn was much larger than when the Farnsworth’s had first arrived, but Lee was still an important man, and involved in political wrangling, running for office in 1943 as part of an upstart political party. He would die two years later; I don’t know what happened to May Farnsworth. Meanwhile, his son was looking for a frontier even vaster than the transformation of a small village into a populous suburb.

Robert worked for a rubber company in the 1940s, according to newspaper accounts—likely Goodyear—but his career was something else: he wanted to guide U.S. space policy—to prompt a rocket to the moon, and the beginning of a new empire. He seems to have been familiar with science fiction, but his main interest, at least initially, was to turn fiction into fact, to make those galactic empires of the pulps into reality. In 1942, he founded the United States Rocket Society. It got a slow start—the society was part of Farnsworth’s signature in a letter he sent to Astounding that year, and there were advertisements in Popular Science—but otherwise the first couple of years were quiet: “Join U. S. Rocket Society! Information, dime. 4108-501 N. Kenmore, Chicago.”

The mid-1940s saw changes in Farnsworth's life, and an explosion of activity by his Society. At some point, he became office manager for Pennsylvania Oil in Chicago. Evelyn and he had two children, a son (Robert) in 1944, and a daughter (Tannissee) around 1947. And Farnsworth learned how to use the press to bring attention to his cause: the world itself seemed to be making science fiction into science fact, and the ‘rocket zanies’ no longer seemed so zany. Launching rockets in the desert, writing cryptic pamphlets no longer seemed the limit. Rockets, like other technological developments, heralded a new development in civilization. And the U.S. Rocket Society was the true prophet of their coming. The 1940s saw a number of amateur and semi-professional rocket societies, including one in Chicago—the Chicago Rocket Society, founded in 1946—but Farnsworth had little to nothing to do with these organizations, attempting, instead, to make his the de facto voice of American rocketry.

The first indication of the more prominent (if not renewed) activity came in December 1944. If one thought of the moon as real estate—who owned it? And how could someone buy property? The question was once pie in the sky—ha!—but with the development of rocket technology, Farnsworth thought, the question was pressing. And so he wrote to the Department of the Interior, wondering if there were rules. The Department noted that homesteading the moon would be controlled by the General Land Office, and the 5,000 (!!) public land laws it administered. That meant anyone wanting testate a claim on the moon had to submit an affidavit of interest and establish a permanent residence on that site within six months of approval. The story of the unusual correspondence was picked up by the Associated Press, and spread over the newswires.

The next month—January 1945—saw Farnsworth hitting his stride. He told newspapers the technology was no longer the problem—the only reasons humans stayed earthbound was financing. And this was a big risk, not shooting for the moon. The Germans might get there first, and drop bombs from the high heavens—or even, as precision increased, from Europe. If, on the contrary, Americans perfected rockets first, and reached the moon, it would be a boon for businesses: humans could settle there, living in specially made rockets while they constructed buildings on the surface. The moon, he said, was a perfect observatory, an excellent vantage for mapping the earth, a laboratory for viewing the weather, and—most importantly—the key way station for interplanetary travel.

By this point, Farnsworth claimed membership in his Society numbered 4,000, four-fifths of whom were in the military. He sent them regular updates, but in 1945 upgraded his publications—the first issue of Rockets appeared in May 1945. Startling Stories, the science fiction, was not impressed with the first issue—nor its price—a truly startling $1 per issue, for what was a relatively small quarterly—it measured about ten pages. Later issues, though, were more professional, and Startling Stories’s reviewer called it excellent, and admitted he had changed his mind. Rockets seems to have inspired Farnsworth to reissue a pamphlet he had written—Rockets, New Trail to Empire.

Farnsworth had originally published the pamphlet in July 1943, but it doesn’t seem to have received any publicity. With his name now in the papers, the piece caught some attention. Trail to Empire expanded the argument he had been making the past several months. It started with a basic description of rockets and their possible uses: carrying mail, carrying passengers, studying the weather, and then dealt with the various technical issues still plaguing rocket engineering: reaching escape velocity, financing their building, discovering the right kind of fuel, design, and how to make certain the rockets could return. He then argued that rockets should be aimed at the moon, as a business opportunity, and as the seed of a new empire. He predicted colonization of the moon would prompt a new Renaissance, as every possible subject from art to economics would be revitalized—with new forms made possible by weightlessness and new opportunities created. [http://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.$b80383;view=1up;seq=9]

Days after the end of World War II, Farnsworth was back in the news. He petitioned the U.S. government for permission to use atomic power in peaceful pursuits: the energy that had destroyed two Japanese cities could be harnessed for space travel. Atomic power could life rockets beyond earth’s gravitation, and could heat astronauts wherever they landed. Farnsworth figured that, with atomic power, the entire galaxy could be visited easily. The moon would still play a key role—it would be the “Chicago of the solar universe,” the place where trade routs intersected. This particular story was carried by the United Press, but variations on it, expressing the constellation of Farnsworth’s concerns, would echo through the press for a couple of years. He appeared on the television special “Exploring the Unknown” in December 1945; when the Army claimed to have bounced radar off the moon, he told newspapers the feat only proved his theories; he predicted that with proper financing the moon could be reached before the 1950s. Interest in the Society was high enough that in 1946, he started charging a quarter to those who read the ad in Popular Science and were inclined to write him for more information.

Farnsworth’s proclamation of a new manifest destiny had varying success among science fiction fans. Startling Stories continued to recommend Rockets through the 1940s, and even opened its pages to Farnsworth. He published “First Target in Space” in the September 1948 issue and “Rocket Target No. 2” in May 1949. The first reiterated, once again, Farnsworth’s idea that Americans should claim the moon. He does take the argument in a different direction, though, contradicting those who thought the moon a ‘dead planet,’ suggesting that there might be volcanic activity, even living beings. (Fellow Fortean Eric Frank Russell was among those who thought a trip to the moon worthless.) I have not seen “Rocket Target No. 2.” He seems also to have contributed to the ‘zine “Alien Culture” in April 1949.

Farnsworth also found a warm reception among Midwestern fans. He became close with Donn Brazier, who published the ‘zine “Embers.” Brazier recommended Rockets no later than the fourth issue, and had Farnsworth on his priority mailing list. The ‘zine ran ads for the U.S. Rocket Society, and included articles in dialogue with those in Rockets. Always publicity-conscious, Farnsworth sent Ember an autographed photograph. Later, the two met, and Ember came away convinced that Farnsworth had solid government contacts.

When Startling Stories first noticed Rockets, the reviewer thought it would be good only for rocket fanatics. Shortly thereafter, Farnsworth incorporated science fiction, and SF fans noticed. British fan Walter Gillings wrote in his Fantasy Review, “Unlike most astronautics journals, Rockets, organ of the U.S. Rocket Society, has sympathetic interest in science fiction, is considering featuring it. Fan magazines get reviews in its columns; it even deals in rumors for which fandom is notorious. Suggests that Raymond A. Palmer, Amazing Stories editor, writes the Richard Shaver ‘Lemurian Hoax’ tales aforementioned; that Editor Campbell, too, does the pieces in Astounding under the name of George O. Smith. Comments: ‘It may explain monotonous sameness of the science fiction digest. Thank Heaven for Van Vogt!’”

Not all the fans, however, were as content with this drift. The fan historian Harry Warner wrote in his All Our Yesterdays, “The rocket group that made the biggest splash in America’s fandom during this decade [the 1940s] was the non-fannish United States Rocket Society. It worked out a deal with me at the start of 1942 that provided it with a page in my fanzine Spaceways for publication of its news. In return, I got an imposing number of new customers: everyone on its membership roster. R. L. Farnsworth, Chicago, was the president. By 1946 it had its own lithographed 16-page publication called Rockets, but the science had become adulterated with mysticism and Forteanism.” In the early 1950s, Startling Stories had switched reviewers of ‘zines, and the new writer was not pleased with Farnsworth’s publication: Rocket's material is definitely of value to those interested in rockets—and who isn't?—but our careful calculations indicate that the ‘zine costs one buck per copy, which seems on the walloping side for seven, pages’ mimeographed~on one side. Included in this -issue are reports on rocket-doings, a plethora of bombastic bleats such as NEW HORIZONS! GET READY! FOR THE CONQUEST OF SPACE! Altogether we found ROCKETS interesting, fairly newsy, and inclined to gurgle in its enthusiasm.”

The matter which most struck in the craw of fans was Farnsworth’s unapologetic imperialism. British writers were especially sensitive to his patriotism. The British Interplanetary Society had been established in 1933 by P. E. Cleator to advocate for space exploration—and its members were anguished by the idea of Americans taking the lead, and doing so for business and country, which stood against the scientific ideal of selflessly sharing knowledge beyond national borders. Arthur C. Clarke, one of the earliest members of the BIS, penned a bitter attack on Farnsworth’s pamphlet, bemoaning his jingoism and water-carrying for American businesses. He feared Farnsworth’s use of “all the most blatant tricks of journalistic advertising” would turn astronautics into a “laughingstock.” Cleator also went after Farnsworth in the Journal of the British Interplanetary Society. Farnsworth replied in the Journal, urging them to get over their differences so that they could focus on getting a rocket to space, but Cleator was not mollified, complaining to H. L. Mencken about him.

In 1952, the author Marion Zimmer Bradley also criticized Farnsworth. He critique came in the pages of Startling Stories and took issue with his underlying assumption: that humankind needed to reach the stars to survive. It was exactly the constant search for new frontiers to conquer that kept humanity in its infancy. Rather than confront problems, people—read: men—lit out for the colonies, the West, anywhere. In the process, they created new problems—the extinction of bison and Native Americans, the creation of a society marred and marked by violence—without solving older ones. Indeed, she suggested, those most likely to head for the frontiers were those incapable of fitting into nora society. So save space exploration for some other time, after humans had stewed in their juices and solved the very many problems that plagued the species. (The editor of Startling Stories argued in return that the desire to see new places and confront new challenges was one of humanity’s great gifts.) Bradley was a woman, and therefore something of an outsider, and she did not like Farnsworth’s championing of the mainstream, the perpetuation of the current cultural order: a cultural order, not incidentally, which had almost destroyed civilization twice in the previous thirty years.

Farnsworth continued on despite the protests against his vision, although the 1940s were to be the high point of his rocket career, at least in terms of the publicity he received. In 1950 and again in 1952 he ran for Congress, but lost badly in the primary to the incumbent Republican Chauncey W. Reed. Rockets continued into the late 1950s, still advertised in Popular Science; however, its price had come down—$1.00 per year for those under 18, $3.00 for those older. By that point, Farnsworth had relocated to Nevada, reaching that state in 1955. He worked as a real estate appraiser and was president of the Tennessee Uranium Mining Company. At some point—maybe in Nevada, maybe while he was still in Illinois—Farnsworth joined the Masons and the Shriners. Evelyn died in 1970. Robert died 3 August 1998, exactly one month after his 89th birthday.

As the commentary by those who knew him and read his Rockets shows, Farnsworth was inspired by Fort, and the Fortean Society. He seems to have known of Fort before he was mentioned in the Fortean Society. In 1945, Henry Holt noted, with amusement, that the U.S. Rocket Society had purchased several copies of Fort’s omnibus: “The United States Rocket Society ordered a quantity of Charles Fort's works—and it's a pity Mr. Fort can't know and relish that fact.” Likely, Farnsworth ordered the books in light of their reprint, but he also may have decided to do so since it was in 1945 that his Society was really taking off. He might have had reason to believe that he would need to share the the books a lot.

His name first appeared in Doubt 14 (Spring 1946), a few months after Holt’s comments—and Thayer (not for the only time) had a very different idea about the Society than his publisher. He saw no paradox with rocketeers buying the books of a man who claimed that the planets were nearby:

“When we were founding the Fortean Society, Charles Fort refused to join. We wanted to name him Honorary President, or to give him some other title, one especially calculated to remove all onus of vanity or self-exploitation, of which he had an insuperable dread. ‘No,’ said he, ‘call it the Interplanetary Exploration Society and I’ll come in, but not as long as it has my name on it.’

“Ever since, we have had the warmest cordiality for the rocketeers, and kept tabs on their progress here and abroad until censorship interfered.

“Now we are delighted to announce that the President of the United States Rocket Society, the well known pioneer in this field, R. L. Farnsworth, and one of the vice-presidents, John M. Griggs are members of the Fortean Society, and will thenceforward be our liaison—transportation-wise—with Luna, Mars, and points up.”

That same summer, Farnsworth’s Rockets advertised the Fortean Society—“The last stronghold of realistic, analytical thought.” And he provided an updated address. US Rocket Society members had been getting their letters returned when they used the address that he provided in the second edition of “Trails to Empire.” (He also recommended subscribing to the British Interplanetary Society, which had recently begun publishing again with the end of the war.)

Life Between Holt’s view and Thayer’s was tenuous though: was the US Rocket Society meant as a serious provocateur for space exploration, or a nose-thumbing joke at the scientific establishment? It wasn’t always clear, much to the chagrin of both the Forteans and their detractors among the science fiction and aeronautics communities.

On the Fortean side, Farnsworth kept Thayer well-supplied with clippings until the mid 1950s (ewhen he relocated to Nevada) many of them far afield of rocketry, and some expressing unexpected political perspectives. His name first appeared in Doubt, actually, a page before Thayer’s comments, appended to a series of clippings about mysterious creatures—what we’d now call cryptozoological reports. He also sent in material about mysterious balls of fire and dead fish washed ashore by the tons (Doubt 15); flying saucers (Doubt 19); a baby strangled to death in sleep by her necklace (Doubt 20); and a pamphlet that was sent home from school with Farnsworth’s son (Doubt 39):

“The 8-year-old son of Rocketeer Farnsworth brought home from school (Glen Ellyn, Ill.) a 16-page ‘comic’ book entitled FIRE AND BLAST! It had been given him by his teacher. It had been published by the National Fire Protection Association of Boston, and in it is reference to a previous publication, AMERICA IN FLAMES.

“The contents is [sic] unspeakably nefarious, an effort to terrify under the do-good cloak of teaching fire prevention. No school teacher fit for her post would put this obscene matter into a child’s hands, but the trick is turned by glorifying Civil Defense in the text.

“SPEAK UP in your Parent-Teacher meeting before this happens to your child. Oppose this ghastly attack upon juvenile mentality before the youngsters are subjected to it.”

Despite his plumping for America and big business, Farnsworth, apparently, also had a libertarian streak like Thayer’s: his must’ve just run in a more rightward direction. And all of these contributions are independent of other times that Farnsworth, and his ambitions, were referenced in Doubt. In addition, Farnsworth joined the third Chapter of the Fortean Society—the Chicago Chapter—during the late 1940s, when Thayer was playing with the idea of having local branches of the Society.

On the aeronautics side, Farnsworth’s peers—mostly in the scientific community—acknowledged that he was technically accurate in his discussion of rockets. Even his critic Clarke acknowledged his proficiency (minus a few howlers). His work was taken seriously enough to attract the attention of professional astronomer (and science fiction writer) R. S. Richardson, who found some of Farnsworth’s calculations shaky. When he stuck to the physics of rockets, and kept his Fortean musings hidden away in Doubt, he found respect.

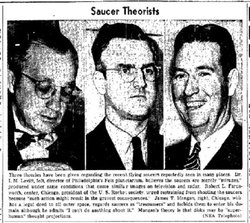

The trouble was, for Farnsworth, Forteanism and rocketry were not separate subjects, but worked in conjunction with one another: the line between science fiction and science fact was too blurred. In a 1947 editorial for Rockets that was picked up by the United Press, Farnsworth surmised that the moon’s craters were left-over from a prehistoric atomic war between aliens. And perhaps those Lunarians came to earth, after that war, and were somehow involved with now-lost continents, such as Atlantis. A trip to the moon, the editorial said, could solve these ancient mysteries. Around the same time, attention was drawn to flying saucers, and Farnsworth chimed in. Don’t shoot! The discs could be electronic eyes from Mars. Or perhaps they were living creatures from Venus. The planet could have evolved a form of life that powered itself through the cosmos with electric current. Farnsworth made clear that these were Fortean musings, noting the large collection of reports Fort had gathered in his books about unusual lights in the sky.

(Incidentally, Farnsworth thus helped promote Fort back into the limelight with the flying saucer flap of the late 1940s. Among those to pick up on his musings was the Chicago journalist Marcia Winn, who became a Fortean and wrote approvingly of the Society in her columns.)

Although I have not read through the entire run of Rockets—it is rare—the consensus from others is that overtime it increasingly included bits of Forteana. A 1946 issue, for instance, included a column called “Fortean Data,” which discussed a weird star; and the books of Charles Fort were listed on the recommended reading. R. DeWitt Miller, a Fortean of good standing, used some of Farnsworth’s material in his Forgotten Mysteries. For science fiction fans who thought of Fort mostly as a stimulant to the imagination, and not at all a serious astronomical thinker, Farnsworth’s blending of the two subjects wrankled. A reviewer for Startling Stories poked fun at Rocket’s attraction to fringe science. Farnsworth’s rag had covered Velikovsky’s Worlds in Collision and decided, ‘This book is good fun and we understand that it is being made into a movie.’ The reviewer snarked back, ‘With Don Ameche as Venus?’ The whole point was to separate rocketry from crankery, to make it a real science, and Farnsworth was hurting the cause.

Thayer, on the contrary, thought Farnsworth to conventional, although admitted his was a necessary tactic. When news broke that radar had bounced off the moon, Thayer wrote in Doubt (14): “Probably he will report upon the recent ‘radar high jinks in the columns of his publication. No advocate of flights to Luna could afford to scorn such an opportunity. For what it may be worth, however, we pass along the observation of MFS Stevens, that such nonsense as the ‘Heaviside layer’ and other ‘ceilings’, which have been ‘bouncing back radio waves’ for ever so long, must have parted like the Red Sea to let ‘radar’ through—round trip!” Farnsworth was “moon-ho”; he had his cause—and the money spent would take away from war, anyway, even if it was all a boondoggle, and the planets, as Fort said, could be reached in short order.

But Thayer had his limits (and he tended to turn on allies, anyway), which Farnsworth crossed. In Doubt 17, Thayer wrote, that there was a “natural affinity of Forteans for the exploratory accounts for the closeness of our association with such institutions as the National Speleological Society and the United States Rocket Society.” But Forteans did not have to agree with those organization, and Thayer took exception to Farnsworth’s call to use atomic power in rockets headed to the moon. Farnsworth had made the comments in the press, in an American Weekly article had had written called “The Moon my Destination,” and in a letter to Senator Wayland C. Brooks. “We wish that this compromise with the Great Atom Fraud were not necessary, but if Farnsworth wants $350,000 to build his rocket he must assassinate his conscience to get it.” Other Forteans had their limits, too, and Buffalo’s B. Goldstein asked about the planned interplanetary empire: ‘Did it ever occur to Mr. F., that someone else may be there already?” For a Fortean Society that was all in with Native American rights, the prospect of a new empire, a new wild west, as Marion Zimmer Bradley had it, was awful. Thayer didn't want to be a part of it.

All of which raises the question, How did Farnsworth reconcile these two views, his acceptance of rocketry’s technical standards with a Fortean contempt for consensual reality? It is not clear from the writing I have studied how he managed to pull this off. But it is also worth noting that he was not the only person who worked at the blurry edge of conventional science and the paranormal. Ray Palmer made a career of it. There were others in Farnsworth’s orbit—Brazier, Griggs—who also sought to combine science and Forteanism. I guess one way to look at it is to say, that these men saw science (and engineering) developing so quickly that they were inclined to allow entirely imaginary parameters for the future. If rocketry had gone from a derided, amateurish hobby in the 1920s to an area of active scientific research in the 1940s—and it had—then who was to say what the final limits were? Why not electric fish flying through the cosmos. Nelson Bond had written a brilliant Fortean short story on just such a topic.

What surprises, then, even if we cannot completely come to terms with how Farnsworth combined these two sets of ideas that other people saw as diametrically opposed, is that the future world he imagined—the world of a science unconstrained by then-current limits, a world of atomic-powered rockets and terraforming and interplanetary trade and a renaissance of art and religion was encysted in such a conventional structure. All that imaginative power, and Farnsworth came up with a reworking of America’s myth of the frontier, manifest destiny, and financial imperialism. As much as the unsavory implications of Farnsworth’s project, the lack of imagination disappoints.