From "Agharta."

From "Agharta." This one is long.

Robert Ernst Dickhoff was born 6 February 1904 in Germany. I do not know anything about his family and very little about his early life. Much later, he remembered that when he was eight—around 1912—and living in a suburb of Cologne, he saw two “little people,” no more than three-and-a-half feet tall sitting against his fourposter bed. Realizing that they had been seen, the naked creatures, humanlike and tan, dissolved into the thing air.

He arrived in the United States in the 1927 (although there is at least one document that says 1925.). The manifest of the ship “New York” shows him arriving in New York on 4 July 1927 from Hamburg. He was a member of the crew, and had been for a few weeks, since 4 June 1927, but had bene at sea for two-and-a-half years. He was not supposed to be discharged in New York, but seems to have jumped ship. According to the manifest he was tall and slim, 5’10” and 166 pounds. He would later admit that he had entered the United States illegally.

Sometime in the 1930s, the family moved into New York City. Another son was born, Ronald, around 1936. The 1940 census has the Dickhoffs living on 85th Street, on the Upper East Side, not far from the river. Dickhoff still worked as a printer; Rose waitressed at a private school, which was apparently a new job: she had worked no hours in 1939. Robert was not fully employed. He reported only 30 weeks of work in 1939, bringing in $1,050 (and paying $30 per month in rent). I do not know have information on what the family did during World War II, but there is a chance that they were viewed skeptically, a family of German and Italian non-citizens.

As World War II reached its conclusion, Dickhoff’s life underwent a major reorganization. The marriage came to an end. In 1944, Robert and Rose separated, according to a later legal case. In 1945, Dickhoff founded the “American Buddhist Society and Fellowship,” according to later published biographies. He seems to have been drawn—when I don’t know—toward an esoteric version of Buddhism that was related to Theosophy or, as he put it, “The Greatest Truths were thus revealed to him in a ‘strange tongue and in a strange land.’” His entrance into this occult realm was blessed by the Lord Maha Chohan, whose he claimed as a friend, but is better known as a Theosophical Ascended Master, associated by Dickhoff with Koot Hoomi, who Madame Blavatsky claimed as a seminal inspiration for Theosophy.

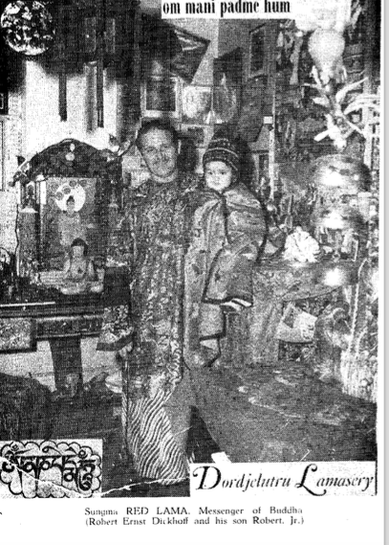

Around this time, Robert—from the States—engaged a Mexican lawyer to draw up a divorce. Rose was served with papers in 1946 and did not contest them. The following year, he supposedly incorporated his Fellowship, with him as Most Reverend Red Lama. On 30 March, he married a woman named Maria, who was some 19 years his junior. They would go on to have three children by 1956. Robert claimed no more than a eighth-grade education, but also that he could read German, English, and Spanish. He continued to work as a compositor. A form filled out in the late 1940s put his height at six feet.

In March 1948, Robert, Maria, and Robert Junior traveled, returning from Puerto Rico 25 April. The trip got Dickhoff entangled with the government. According to the “Information Sheet” for the Immigration and Naturalization Service that Dickhoff filled out, he was returning to New York to meet with relatives, Frank and Ronny Dickhoff. Ronny was apparently his son Ronald; I’m not sure who Frank Dickhoff was. The problem was that he was—as he wrote—“stateless.” He had no proof of residence, telling the immigration official that he had come to the States on 4 July 1927, but having no documents. Th bureaucratic wheels turned, and in the fall of 1948, he had a deportation hearing. I have only seen a reference to it, not the article itself, but in November, the Associated Press carried a story in which Dickhoff, calling himself the “Red Lama,” testified on his own behalf.

According to a later court case, the Board of Immigration Appeals declared him deportable. The case dates this decision as November 1949, but that seems wrong—November 1948 fits better. Whatever the case, the Board stayed the proceedings and offered Dickhoff the right to leave the country voluntarily and re-enter the country legally, clearing up his status. Apparently, though, Dickhoff had bigger matters on his mind. He failed to take advantage of the offer in the time allotted, and so the order of deportation was reinstated.

Among those bigger issues was Dickhoff’s occultism. He put out a collection of essays—that also included some of his own artwork—under the title “The Eternal Fountain, a Kaleidoscope of Divine Inspired Thought Sparks.” The book was published in 1947 by Bruce Humphries, Inc., in Boston. It was copyrighted (again?) 13 June 1949 (with no mention of an earlier edition). The introductory note gave Dickhoff’s spiritual lineage and also the titles “D.D” and “Ph.D.” I have no evidence that Dickhoff ever attended college or that he ever earned a Doctor of Divinity or Doctor of Philosophy. In a later work, he claimed the degrees were received in 1946 from an institution called the “American Indian Association, Incs.” I have tried to read the book, and not found much of originality. The early chapters are written an oracular tone, not gnomic but vague and allusive, and it is hard to extract meaning from them, at least for me.

The vast bulk of the book is reworked Theosophy and 19th-century New Thought. He thinks that humans will return to a more primitive, pre-civilized state soon—and that this is a good thing. The change will occur “as soon as modern science is through wasting its time, money, and labor on experiments and inventions benefiting only a wealthy few and exploiting or destroying millions of their fellow creatures.” And behind all of this—so-called civilization and science—was greed. In another essay. Dickhoff argued that thought existed separate from the human body and could continue after death—suggesting, therefore, that death should hold no horror. (Along the lines, he claimed that suicide was neither good nor bad—life is not worth worrying over.) There’s another bit that seems to presage Dawkins “selfish gene”: that humans are mere fleshy puppets of the germ plasm. For all of his call to go back to nature, Dickhoff seemed to abhor actual nature, the organisms that exist.

Another part of the essays is clearly borrowed from American science fiction and fantasy. Dickhoff was apparently reading his “Amazing Stories.” He incorporated bits of the “Shaver Mystery,” though rendering it vaguely. Evil and good, he says, are projected onto humanity via rays—though he is coy about their origin, suggesting outer space but ultimately non-committal. Their existence has been obscured by religion, which call them God and the Devil, rather than seeing them as actual forces. (Here, then, he is rooting for a scientific understanding, such as it was, against a religious perspective.) Cosmic rays, he thought, were the key to understanding man’s impulses—the warring impulses the once destroyed Atlantis and now threatened to destroy modern civilization, unless humans came to their senses and saw the universe as he saw it.

I do not know what else Dickhoff was doing in the years immediately after he published his collection of essays, exactly, but apparently he was at least continuing his study, promoting his society, and sorting out his immigration status. Between 1949 and 1952, he applied for suspension of deportation two different times, once under the authority of the Immigration Act of 1917; and once under the aegis of the Immigration Act of 1952, which gives some sense of how long the process continued. In both cases, though, his application was denied. The problem in the first case was that Dickhoff admitted to being a member of the Communist Party in 1929 or 1930, which rendered him unfit for suspending the deportation order. The problem in the second case was that he did not meet the criteria for having “good moral quality.” The state refused to recognize his Mexican divorce, which meant he was committing adultery by having married Maria.

Meanwhile, he claimed to have been given a title by the Dalai Lama in 1950. He seems to have been aware of the BSRA and N. Meade Layne. He also seems to have taken notice of the writings put out by another Fortean and Buddhist-inspired prophet, Maurice Doreal. He knew of the so-called Emerald Tablets, which were supposedly translated by Doreal. According to him, these tablets had been set down by the Atlantean Thoth—and he had gained access to them in the 1920s—giving a secret history of the world that recounted a long ago war between humans and a serpent people. In one pamphlet of uncertain vintage—though after 1947—Doreal associated these serpent people with extraterrestrials. This connection may have revised a(n earlier?) pamphlet that had the serpent people as extinct.

Dickhoff continued to read “Amazing Stories,” too, paying special attention, it seems to the Shaver Mystery and to tales about Tibet. W. C. and Ginny Hefferlin claimed in the magazine’s pages to have been in telepathic contact with Tibetan masters and have learned about amazing inventions; the Hefferlins’s ideas were, against their wishes, folded into the Shaver Mystery. (They took to N. Meade Layne’s Borderlands Science Research Association to decouple themselves from Shaver.) The Hefferlins spun an alternative history of earth, in which the planet was once colonized by Mars before catastrophe struck in the form of an invasion by the snake people. The connection to stories being written for the “Weird Tales” crowd is obvious. Others were also promoting Tibet as a source of (Deros) evil in Amazing Stories, including Fortean (and BSRA member) Vincent Gaddis.

Dickhoff synthesized these stories with another tale being promoted in “Amazing Stories”—and other occult publications—that of Agharti, a secret underground city ruled by the King of the World, an adept, possibly from space. In 1951, he put out “Agharta,” published again by Humphries in Boston. Thin like his earlier book, Agharta was plumped by a vamping introduction as well as a disquisition on esoteric Buddhism conclusion. To those who have taken the time to study Dickhoff’s ideas, they are ridiculous on their face, the pretensions toward Buddhism and theological rigor undermined by his ideas’s obvious roots in poorly written science fiction and recently-minted occult theories of the earth’s history. “A truly—and unintenionally—comical version of the Aghast legend,” said Walter Krafton-Minkel in his essential “Subterranean Worlds.” Jocelyn Godwin said that taking in Dickhoff’s ideas, the reader realized “we are scraping new depths.”

The core of Dickhoff’s booklet was a story of how Mars colonized earth long ago, created humanity, and set it toward its Golden Age; Venusian snake people saw what was happening on the third rock from the son and also found there way here. Harassment by the serpent people forced the Martians and earthlings to build underground cities—Shambala beneath Tibet and Agharta below China even as humanity continued on the surface and the Martian gods incarnated themselves as humans. The serpent people again copied, and infiltrated the city governments as “Black Magicians”—a concept borrowed from Theosophy. Eventually full atomic war broke out, destroying most of civilization. The Martians retreated to Shambalah and the Venusians to Agharta (they called it Agharti). He did not make the point, but these were the Deros and Teros. War continued for millennia until 1948 when the serpent people were mostly routed.

But the Venusians were not done; they were working with scientists and had helped humanity (re)discover nuclear weapons. The serpent people nudged governments toward war again—just as had been the case when Atlantis and Lemur destroyed each other and nearly the entire world. They were also involved with the UN. The plan was to destroy the world, then eat humans in the Gobi Desert. (The Gobi Desert was important to Doreal as well.) Meanwhile, the Martians were rallying. Amid this, Dickhoff offered something of a third path, in the form of his esoteric Buddhism, which preached a peace unknown to the martial races, Venusian or Martian. A better day might be dawning, and it could be brought sooner by humans perfecting space travel on their own. There were signs and wonders. The result was unclear, but this period was critical in human history: destruction repeated or a new, peaceful society would soon reveal itself.

“Agharta” did not receive wide dissemination, but Dickhoff continued to move in occult and science fiction circles. He sent a letter in to “Fate” magazine. He supposedly gave lectures. His lamasery was reportedly a bookstore, and so he may have moved from publishing to selling books. This was t 315 E. 107th Street, New York. N. Meade Layne read Dickhoff’s booklet and wrote approvingly of it in “Round Robin” March-April 1953. He made the papers in 1954 for circulating a picture of the Dalai Lama that he said he’d obtained from a Nepalese merchant.

In 1956, his case suing the INS to set aside his deportation—which had been entered in March—was heard in federal court. The judge admitted that under the 1917 law, Dickhoff was unfit for the setting aside of deportation. But supreme court decisions and the 1952 law had given the attorney general more discretion in making decisions and had made mere membership in the communist party insufficient for deportation. So the case really are down to whether Dickhoff’s supposed adultery counted as bad moral character. The judge decided that Dickhoff’s adultery was a technical glitch, not a sign of bad moral character. He invalidated the deportation order. That was in May. It was two months short of 18 years later—in March 1974—that Dickhoff was finally naturalized.

The year following his court victory, Dickhoff was associated with he publication of “The Martian Alphabet and Language,” which purported tone a condensation of the 1898 book “From India to the Planet Mars” by Théodore Flournoy. In 1958, Dickhoff published another booklet, “Homecoming of the Martians: An Encyclopaedic Work on Flying Saucers. This one was put out not by a Boston publisher but one in India, Ghaziabad, India: Bharti Association Publications. It ran to 175 pages. I have not seen it. Reports have it that the book comprises a bunch of news clippings (“Homecoming” was dedicated to Charles Fort) with commentary. These same reports have it that he is still worried over the creating of life—still chary of biological processes—and worried, too, over a bio-engineered brain that subsists on the blood of captured humans. The Manichaean battle between Good and Evil continues to wage. (Dickhoff seems aware of some Gnostic literature, connecting the serpent people to the reptile in the Garden of Eden.) “Homecoming” was advertised in “Fate,” among other places, with Dickhoff’s other works.

To me, his life becomes increasingly opaque beginning in the 1960s. He published one more work of obscure esoterica of which I am aware. On 15 July 1968 he self published “Behold, The Venus Garuda,” a small work—71 leaves, according to the copyright notice. (By this point, according to the copyright, he was living at 600 W. 157th Street—the same address he would have when he was naturalized 6 years later.) The title evoked John 1:29—“Behold! The Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world”—but replaced the absolver with a Babylonian god, Garuda, the birdman, an extraterrestrial that tends to humans as meat for its sustenance. In this account, Venus—still home to the serpent people—was a space station created for the Garuda to nest, and the base from which they raid earth. He read the history of religions in light of this set-up, finding evidence for giant birds in various mythologies, re-interpreting the Bible: for him, religious leaders cloaked the true nature of God—giant man-eating bird aliens—in more benign terms to maintain their political power. But it was’t just traditional religions that were the target of his attack (as science had bene in his earlier books). New Age religions also took their brickbats, as well, particularly the modern “Bible” promoted in so many of Ray Palmer’s publications, The Oahspe.

Dickhoff was also involved with alternative forms of medicine, and opposition to American mainstream practices. He had said as much in “The Eternal Fountain,” objecting to modern medicine and arguing against insurance. He had some association with Walter Siegmeister, aka Raymond Bernard, a health food advocate, vegetarian, and opponent of pesticides, who in 1960 wrote a book on Agharta. In 1964, his “Agharti” was republished by Health Research Associates, which put out a whole lone of fringe books, particularly, as the name suggested, on alternative forms of medicine.

Dickhoff continued living at apartment 56, 600 W. 57th Street, New York, through the 1970s and into the early 1980s, at least. This home remained the center for the “American Buddhist Society and Fellowship, Inc.,” though I do not know what—if anything—the Society was doing. At some point after 1983, he moved to the state of Washington.

He died in Bellevue on 27 July 1991. He was 87.

******

Reconstructing Dickhoff’s Fortean history presents something of a challenge: the dearth of direct evidence. He was mooning about New York City, and quite possibly interested in occultism and esoteric forms of knowledge, when Fort had returned from his sojourn to England and published his two last books. He was there in 1931 when Thayer and a cast of literary iconoclasts formed the Fortean Society, and there in 1937 when Thayer relaunched it. He was reading science fiction and its occult accomplices at a time when both would have mentioned Fort, sometimes quite prominently: his name came up several times in Palmer’s publications. And he was conversant with the writings of other Forteans—Vincent Gaddis, Harold T. Wilkins, N. Meade Layne, Maurice Doreal.

In short, it is impossible to think that Dickhoff wasn’t at least aware of Fort, whether he had read any of his books or not, by the time that “Agharta” appeared in 1951. And there are some subtle reasons to suspect that the connection dated back further, though these, of course, are not dispositive. Still, there’s the phrase from “The Eternal Fountain” in which Dickhoff is discussing alien life from other planets. He called these “new Lands in the Sky.” It is difficult not to hear an echo of Fort here. There’s the “New Lands,” the title of Fort’s third book, published in 1925. Fort had argued that the planets were not far away, but close, reachable by a small journey—not in space, then, but “the sky.”

I have found no references to Fort, direct or otherwise, in “Agharta,” but there is still an homage of sorts. Dickhoff compiled newspaper clippings, and wove them into his account. He noted anomalous reports of early-coming springs might be a sign that the earth was about to embark on a more cosmic rebirth. I have not seen “Homecoming of the Martians,” but the one description I have read of it indicates it, too, included digests of newspaper reports; these he related to presumed kidnappings and disappearances of humans—just as Morris K. Jessup did. In Dickhoff’s hands, mysterious disappearances were proof humans were being harvested as food.

Which brings up another way in which Dickhoff’s books owed an obvious debt to Fort, either directly or via some (science fictional) intermediary. One of Fort’s dos famous suggestions was that humans were property. Eric Frank Russell used it as the basis of his “Sinister Barrier,” in 1937, and other science fiction writers were similarly inspired. There’s an elective affinity between this idea and H. P. Lovecraft’s old gods, which were repurposed in Dickhoff’s cosmogony as Martians and Venusians. Humans were the literal property of Martians in “Agharta,” created by them. In “Homecoming” and “Behold,” they were more figurative property, gathered to feed godlike beings. Fort wrote, in “Book of the Damned,” “I should say we belong to something: That once upon a time, this earth was No-man’s Land that other worlds explored and colonized here, and fought among themselves for possession, but that now it’s owned by something.”

As it happens, Dickhoff mentioned Fort explicitly in “Behold—the Venus Garuda.” Which makes sense given how Fortean the book is—although mostly in the same way as his earlier books. There’s the sense that humans are something else’s property. News clippings are woven into his story. There’s the alternative cosmology based on the slender reed of a few stray facts. There are Fortean science fiction resonances—in this case Nelson Bond’s “And Lo, the Bird” (1950) which posited planets as eggs for giant space-dwelling birds. He called America’s space probe Mariner II a “spatial fishing pole,” which evoked Fort’s idea that humans were being fished for. Fort, Dickhoff noted, mentioned interplanetary tourists possibly visiting the earth, who were sometimes called angels and were lean and hungry: Garuda, then.

There is a bit of confusion here, though, which accounts for the difficulty reconstructing Dickhoff’s Fortean history. Introducing Fort, he says that he did not read “Book of the Damned” until 1964—though he himself admits he had dedicated his 1958 “Homecoming” to Fort. “Book of the Damned” included the passage about humans being property. It seems unlikely that Dickhoff had never read this book before—though not impossible. Perhaps he had read the rest of Fort’s corpus. Perhaps he absorbed Fort’s ideas through the conduit of science fiction. Or perhaps he was simply wrong. In the end, I guess it doesn’t matter a whole lot, because Fortean ideas ran through Dikchoff’s writings, regardless of how much credit he decided to give to Fort.

Dickhoff also had some dealings with the Fortean Society, though these were minor in comparison. All told, his name appeared in “Doubt” three times between 1954 and 1958, and in none of the correspondence that I have examined. The connection between him and the Society were as obvious as the connection between Dickhoff and Fort. Indeed, one could say that his ending up in the Society was overdetermined. In addition to all the other contacts listed, Dickhoff was also a dissenter when it came to medical matters, and so was Thayer. It is worth noting, too, that though Dickhoff was not among the earliest of Forteans, coming to the Society no sooner than the mid-1950s, his joining was much before he supposedly first read “Book of the Damned,” suggesting he was, in fact, familiar with Fort before the publication of “Homecoming,” let alone “Behold.”

It is impossible to extract any more information about Dickhoff’s Forteanism from his appearances in “Doubt”—except that Thayer recognized Fort in his writings. The first two citations were generic credits, Dickohoff’s name in a long list of acknowledgments in each case, “Doubt”s 44 (April 1954) and 57 (July 1958). The only thing that we might say is that Dickhoff was a dues-paying member, except even this has a caveat: Thayer only listed a surname, so it is possible that there was another Dickhoff altogether who belonged to the Fortean Society and sent in material. Usually Thayer was good about providing an initial if he had more than one member with the same last name, but that was not always the case, and it is possible that two Dickhoffs were members in succession, rather than parallel.

The third mention was the most substantial. In it, Thayer called out Dickhoff’s “Homecoming,” and praised it for its Fortean bearing. The reference came in a column on books of interest to members (Doubt 58, October 1958). Thayer wrote, “A curio of curios for the saucer addict has been prepared by Dr. Robert Ernst Dickhoff, MFS, Ph.D., Sangma Red Lama of the White Lodge of Tibet . . . of New York, Buddhist, Ufologist, and any number of other things. It is called “Homecoming of the Martians/An Encyclopaedic work on Flying Saucers” and it is dedicated to Charles Fort.”

Thayer then continued, “Let me tell you nobody would have enjoyed the production more than Fort himself. I wish that I could have sat with him discovering it page by page. . . It is illustrated, mister, and I mean illustrated . . . Altho Dickhoff is a resident of N.Y.C., this book was made wholly in India, and was ‘bounded’ by hand. Typographical errors are quite numerous, but I assure you, you won’t mind.

“Some exception must be taken to the use of the word ‘Encyclopaedic' in the subtitle. It is more in the nature of a scrap-book, beginning with a poem by Lilith Lorraine, and ending with a letter from ‘H.R.H Mysikiitta Fa Sennta, High Priestess Helien Temple.”

The ideas promulgated by Dickhoff survived him and the Fortean Society. There was an inherent conservatism in them—the prophet’s demand that Society turn away from its false idols and return to the practices of a Golden Age. (Hos conservative outlook may be what drew him to the Fortean Lilith Lorraine.) Dickhoff stood against what he saw as the world’s corrupt institutions—religion, science, and government (not incidentally the three-headed beast battled by Fortean Art Castillo). There was an obvious paranoia, too: that these institutions had bene infiltrated by outsiders who wanted to turn humans into food. Dickhoff’s conservative Theosophy would form the basis of later conspiracy theories, especially those of David Ickes. One could even hear their echoes in the “X-Files.” It was through Dickhoff—and those who shared his worldview—that the line between fiction and non-fiction was eroded, giving birth to movements at the end of the 20th century and beginning of the 21st that radically refused such divisions. Fort, too, was essential to this process, not only by influencing Dickhoff, but in his own writing, which similarly blurred—if not quite to meaninglessness—the border between fact and fantasy.

Our postmodern world began here.