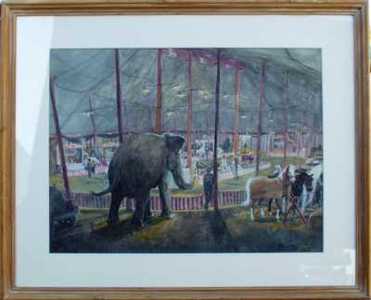

A painting by RBJ.

A painting by RBJ. Yet another mysterious Fortean.

This write-up is a revised and (slightly) updated version of a series of posts I first did back in 2009 (!) and 2010. It seems to be the un-cited source for much of the wikipedia entry on the man.

Robert Barbour Johnson was born on 19 August. That much we can say with some certainty. It's the date given on his application for a social security number and on his death certificate. Beyond that, well, there's a range of possible answers. His World War II enlistment card says 1905. His application for social security says 1906. Obviously, there are incentives for making one's self older to get social security earlier. There are also incentives for making oneself younger and some suggestion Johnson relished the idea of being a wunderkind. When his story "Far Below" was chosen as the best yarn ever published in Weird Tales, he was noted as one of the magazine's younger writer. He said that he harassed his writer friends with that for month, pointing out that lots of people say they are young, but he had written proof. His death certificate says 1907 (as does the SSDI). His recollections for The Weird Tales Story suggests that he was born in 1909. Edan Hughes's “Artists in California” has him born in that year as well.

This write-up is a revised and (slightly) updated version of a series of posts I first did back in 2009 (!) and 2010. It seems to be the un-cited source for much of the wikipedia entry on the man.

Robert Barbour Johnson was born on 19 August. That much we can say with some certainty. It's the date given on his application for a social security number and on his death certificate. Beyond that, well, there's a range of possible answers. His World War II enlistment card says 1905. His application for social security says 1906. Obviously, there are incentives for making one's self older to get social security earlier. There are also incentives for making oneself younger and some suggestion Johnson relished the idea of being a wunderkind. When his story "Far Below" was chosen as the best yarn ever published in Weird Tales, he was noted as one of the magazine's younger writer. He said that he harassed his writer friends with that for month, pointing out that lots of people say they are young, but he had written proof. His death certificate says 1907 (as does the SSDI). His recollections for The Weird Tales Story suggests that he was born in 1909. Edan Hughes's “Artists in California” has him born in that year as well.

Johnson appears twice in the U.S. census. In 1930, he claimed to be 22. That census was taken in April, which would put his birth in 1907. At the time, he was living alone, in San Francisco, and so could have been fibbing about his age. Ten years earlier, though, when he was still living with his parents, his age is given as twelve. Since he was censused in January, that would again put his birth date as 1907.

So, then, he was born in 1907. But where? All the public records give his birth as Kentucky, and Johnson himself says it was Hopkinsville, Kentucky, in Christian County, which makes some sense—both of his parents died in there. The one discordant note is the 1920 census, which gives his place of birth as Ohio. Perhaps the issue could be settled with a birth certificate? No doubt. Unfortunately, Kentucky did not keep good records before 1911, and previous searches for Johnsons in Christian County have come up blank. Ohio organized its birth records by county until 20 December 1908, and the census gives no indication what county Johnson was born in. Hopkinsville is in the far southwest corner of Kentucky, nowhere near Ohio, and so it is not even possible to check with bordering counties.

These are the problems inherent in trying to reconstruct Barbour's life. He once called himself—in homage to one of H.P. Lovecraft's stories—The Outsider. And there's a lot of truth to that. Indeed, I am not the first to go in quest of Johnson's history. R. Alain Everts did before me, and he came up with nothing. I think I've had a little more success.

His father, Robert Jefferson Johnson, was born in November 1869 to a farming family in Holmes, Mississippi, according to the 1880 census. His future wife, Mary Barbour Legrand, was born about 1865 to a farming family in Kentucky, according to the same source. I can't find them on Ancestry.com again until 1920. If Robert Barbour Johnson was born in 1907, then his father was thirty-seven and his mother forty-two. At least according to the 1920 census, he was there only child. One wonders of they had earlier families, given the relative lateness of this one. At any rate, it seems that the trio moved around a bit. They were probably in Hopkinsville, Kentucky, during Johnson's early years. They were in Louisville for the 1920 census. They were in New Orleans in 1930, according to the census (and Johnson's memories—although those seem to be quite shaky on actual dates). Robert Jefferson and Mary B. both died later in the decade, 1933 and 1934, respectively.

In the both the 1920 and 1930 census, the Johnsons were boarders in group homes. Mary B. was a housewife. Robert Jefferson worked for an unnamed railroad company, in 1920 as a claims agent and in 1930 as part of the railroad's secret service, which was responsible for preventing crimes against railroads. It was in Louisville that Johnson first encountered “Weird Tales” when he found the an issue on a newsstand near a fire station. He was an "inveterate reader" of other pulps and was turned off by Weird Tales poor production, but fell in love with the stories. “It contents! Ye Gods, its contents!”

According to Johnson, he wanted to be a writer ("among other things") at least since high school. He tried a few stories for Weird Tales—all rejected—but was otherwise more interested in journalism. Supposedly, he took journalism courses at Tulane while the family was in New Orleans, but no record of his attendance has been found (which doesn't mean he lied; it's likely a problem with the records, since it seems that Johnson never actually received a degree). He also supposedly worked for The New Orleans Item, writing stories first as a summer job and then beyond that—seeing his stories in print quickly and getting paid for them, also quickly, more rewarding than grinding out a magazine story that might not appear in print for months with payment only coming upon publication. Exact dates for this employment history are hard to nail down, first because of uncertainty surrounding Johnson's birthdate and second because his "specialty in those days" was pretending to be another age—apparently the start of a life-long habit. "I looked, talked and acted at least five years more than my age, and was able to pass as an adult without question," he said later.

While in New Orleans, he also found another love: the circus. While there, he agreed to be a press agent for a traveling circus, according to his memoir in “The Weird Tales Story.” As he recounted there, he passed through most of Canada and the U.S. during his summer stints (he was still enrolled in Tulane otherwise). Quickly bored by his duties, he “discovered a new talent, that of animal training. I was soon handling dogs, ponies, goats, horses, and even camels.” I have uncovered no confirmatory documents, which is not a surprise. Circuses performers are notoriously hard to track—circuses are where people run away to, where they go to get lost. There’s no special reason to disbelieve Johnson, and some things which give credence to his story. He was also well known for training his pet cat, "Kitty K." Clark Ashton Smith's wife, Carol, commented on it in a letter. And at the 1956 West Coast Science Fiction Conference (Westercon), Johnson's pet performed—in the words of the Oakland Tribune—“35 stunts you wouldn't normally expect a cat to do. Unless it was Jueles Verne's cat.” He wrote about circuses often for the pulpish magazine Blue Book throughout the 1940s and 1950s, as well as a few articles for some smaller magazines. Here's a probably incomplete bibliography, from the FictionMags Index:

# The Big Hitch Blue Book Feb 1948

# Animal Man Blue Book Apr 1948

# Elephant Boss Blue Book Aug 1948

# White Horse Pioneers Blue Book Nov 1948

# Lion-Tamer Blue Book Dec 1948

# Parade Wagon Blue Book Feb 1949

# The Man Who Didn’t Like Dogs Blue Book Apr 1949

# Buffalo Bill Holds Five Kings Blue Book Jun 1949

# Truck Show Bull Blue Book Aug 1949

# Liberty Horse Blue Book Dec 1949

# Grift Show Parade Blue Book Apr 1950

# The Big Herd Blue Book Jul 1950

# Zebra Team Blue Book Dec 1950

# King of the Cage Blue Book May 1951

# Longneck Blue Book Jul 1951

# John Robinson Rides Four Blue Book Dec 1951

# Killer Lion Short Stories Dec 1958

# The Clown Short Stories for Men Aug 1959

But even if—and it's only a slight if—Johnson never joined the circus but only invented these tales, it is nonetheless true that the circus world meshed with his continued interest in the fantastic. He met someone, he said, for example, who planned to hunt for the Sasquatch at a time when the creature was not well known outside the confines of Canada. And in a world of actual freaks, the weird stories he favored seemed a lot more plausible.

According to Johnson, he quit the circus in New York, tried to live in New York City but fled the winter and went home again to New Orleans before heading to San Francisco, drawn by its literary and artistic communities. He says he left the Big Easy for the City by the Bay in 1931, but the 1930 census puts him in San Francisco already, living in a group house on Fifth Street, his job listed as essayist. In time, he would move to what he called an “artist's shack” at 1443 Montgomery Street in Telegraph Hill, not far from where Coit Tower was built in 1933. He lived in a basement apartment, but when he came out, Johnson would have been able to track the building of the Oakland-San Francisco Bay Bridge from his street.

This was a critical time in Johnson's life, but it's difficult to get an exact handle on it. It seems clear that he came to San Francisco to make his artistic mark, and in his remembrances for “The Weird Tales Story” he tells of meeting some of The City's leading literary lights—John Steinbeck, William Saroyan, Herb Caen. R. Alain Evarts, however, contacted Caen much later, and the newspaper columnist had no memory of Johnson. As well, some of Johnson's recollections just don't ring true. He said that he was welcomed into the literary circle in part because he had read every issue of Weird Tales and corresponded with the editor, he was considered an expert on the magazine—at a time when "every celebrated author in town was trying to get a story into it; and most of them had failed.” It's hard to believe Steinbeck, Saroyan, or Caen were trying to break into Weird Tales, which calls into question a lot of Johnson's memories of the time.

Apparently, Johnson lived alone during his time in San Francisco, but for his cat(s?). In an article for the fanzine New Frontiers Johnson wrote, “I am as interested in sex as the next man,” but he never married, and I've come across no evidence that he had girlfriends. That doesn't mean he didn't have any girlfriends, but his lifelong bachelorhood—like George Haas’s--certainly raises question about his sexuality. That may also explain his feeling of being an outsider. Still, he did find a community of sorts. At some point, he met up with George Haas and, through him, Clark Ashton Smith, and Smith's wife, Carol. He also knew Anton LaVey, who would later found the Church of Satan. (Through a church administrator, LaVey told Everts that he had known Johnson since 1947, when both were in the circus. That's obviously wrong—but then LaVey is known to have fabricated parts of his past when it suits him.) He seems to have been an important part of the 1956 Westercon—and that might help explain Johnson’s recollections.

The San Francisco Bay Area—San Francisco and its suburbs, Oakland, Berkeley, Palo Alto, maybe stretching the definition enough to include the Monterey Peninsula—was a hotbed for science fiction and fantasy writing in the years around World War II. Perhaps, then, he inflated the literary merit of this welcoming community by combining them with Steinbeck and Saroyan in his memories. (That's not to say some of the science fiction writers—including Anthony Boucher and Philip K. Dick were not excellent authors or, in Boucher's case, editors, but their fame is not that of Steinbeck’s.) Certainly, the pulp writer Garen Drussai has fond recollections of Johnson, and Clark Ashton Smith's wife also wrote warmly of him. It's possible, given his background, he had some of the Southerner's charm.

That Robert Johnson Barbour sometimes wrote for Weird Tales's sordid sisters (pseudonymously, of course) did not mean that he was too intimidated to write for it. "Lead Soldiers" appeared in the December 1935 issue, followed by "They" in January 1936, and "Mice" in November of that year. Johnson, though, remembers the publication history differently, writing that "They" was both the first accepted and published—which is interesting given what I think is its resonance in the San Francisco Fortean community. According to Johnson, he based the . . . well, let's call it tale . . . on “a peculiar glen I had discovered down the Peninsula, with a strangely unpleasant atmosphere." The tale, in Johnson's accounting, "had neither characters, action or plot; but it was definitely weird.” I suspect that this is the same glen that came up in conversation between George Haas and Clark Ashton Smith's wife. Haas seems to have asked her about such a place near Pacific Grove, where the Smith's were living, and she responded:

“George, I found your ‘magnetic field’ as Hazel Dreis calls it, tho she says: Near San Luis Obispo . . . . She has been there not once but twice with friends.” Hazel Dreis did not feel any sense of oppresion, as Haas (and Johnson?) did—that she experienced near Pt. Lobos, which Smith also had sensed. Rather, the glen made her feel “magnetized" and her legs “tingle.”

This sense that the world had uncanny places was central to Weird Tales (and influenced the development of Forteanism in the San Francisco Bay Area). And so it's not necessarily surprising—but it is a testament to his skill—that "They" was well-received by readers of Weird Tales. Johnson's other two stories also provoked fan mail, "Lead Soldiers" even prompting H.P. Lovecraft to write a congratulatory note.

But despite the accolades, Johnson continued to feel "always the Outsider." He thought that the editor of Weird Tales, Farnsworth Wright, didn't like him. Wright, he complained, never wrote a personal note of acceptance, always said that the stories would need careful editing (although according to Johnson nothing was changed), and perpetually complained that a page was missing from Johnson's story—which is either an eccentricity on Wright's part, or something like paranoia on Johnson's. After "Mice," Johnson had two articles rejected; these, he said, were perfectly good—one was later sold to Weird Tales—but reflected Wright's dislike for Johnson. (In fact, Wright was famous for his idiosyncratic rejections.) And so he stopped publishing there for a few years.

It may be that this is when Johnson started publishing for Rogers Terrill’s magazines; or maybe he made his money some other way. Perhaps he was a frequent contributor to the pulps; but none of his remembrances indicate this, and so suggests both the kind of writer he was as well as raising some questions about his livelihood.

Some Weird Tales writers are best understood as literary snobs. H.P. Lovecraft hated the idea of writing for money—it sullied the art. There was some of this attitude in Clark Ashton Smith. Others, such as E. Hoffman Price—another Bay Area fantasy writer and Fortean (kind of)—were professional writers. They paid attention to markets, understood what editors wanted, and created that, selling hundreds of stories over the course of their lifetime. Johnson, it seems, at least from the bibliography that now exists, was of the former type. Unknown is how he made a living. Hoffman sold enough stories to live; Smith supplemented his literary and artistic endeavors with manual labor. What did Johnson do?

He claims that his paintings sold well enough to keep him in food and clothes, as did writings for local art publications—although he doesn't say which one. He also wrote a book on Golden Gate Park—The Magic Park—but that wasn't published until 1940, so hardly could account for an income in the late 1930s. And so the question remains: What did Johnson do?

Whatever else Johnson was up to in the 1930s, he says that he drifted to San Diego for a time—there's no record of this, but also no reason to disbelieve him—and, while there, started writing for Weird Tales again, producing a letter for the May 1939 issue and three stories, "Lupa," "Silver Coffin," and "Far Below." “Lupa" included a nude scene in hopes that it would make the cover—Weird Tales's covers at the time featured nudes. Apparently, it was acceptable to finesse a nude scene into a story for Weird Tales, by Johnson's reckoning, but not so much for Terror Tales. "Far Below" was an homage to H.P. Lovecraft, was once named as the best story printed in Weird Tales, and was widely anthologized. ("The Silver Coffin" was also anthologized.)

That ended Johnson's association with Weird Tales (but not weird tales), with "Lupa" appearing in January 1941 (by which time Farnsworth Wright was no longer editor, part of a series of cost-cutting measures that also led to a decline in quality).

In 1940, he published his The Magic Park, about the Golden Gate Park.

He was drafted into the US Army as a private on 6 November 1942 (Serial Number: 39112693). According to his enlistment record, he was back in San Francisco at the time and gave his birthdate as 1905—making him 37 rather than his (actual?) 35. If it wasn't a mistake, why he would give a wrong age is not clear. According to Dan Sebby, Director and Curator of the California State Military Museum in Sacramento, the unit to which Johnson was assigned (Service Command Unit (SCU) 1952) was the permanent garrisoning party stationed at Fort Rosecrans, and so Johnson would have been involved not with the artillery batteries that were stationed at the Fort but to housekeeping services.

****

After the War, Johnson returned to his basement apartment at 1443 Montgomery—at least that's what Don Herron's timeline would have—and resumed his literary life. Not that he took care of his books. Again according to Herron, the first thing he did with a new book was break its spine so that it was easier to read. And George Haas once discovered that he had been using a slice of bacon (!) as a bookmark. He made miniature circus dioramas, and was mentioned in the novel "Laughter on the Hill," about the dissolute lifestyle among Bohemians and ex-soldiers in San Francisci during and just after the war.

In the late 1940s, he signed a contract with Blue Book magazine for six circus stories and novellas each year. He wrote in The Weird Tales Story that he made "ten times" as much as he did for any of his weird writing. At the time, Weird Tales paid about 1.5 cents per word for stories. According to Paul Reynolds's The Middle Man, Blue Book was paying about 7.5 cents per word—not quite ten times as much, but still a substantial increase.

Blue Book, at the time, was filling a niche between the pulps and the slicks such as Redbook and Saturday Evening Post, offering quality fiction at a lower cost and open to lesser known authors than those magazines. Its competitor was Argosy. Argosy was one of the first pulps; it had declined seriously by the end of the 1930s and was purchased by Popular Publications—the upstart company where Rogers Terrill worked. Eventually, he was given command of that magazine and raised its quality—surprising given his earlier interest in the sexploitation pulps. One wonders whether Johnson did not avoid Argosy because of his past associations with Terrill.

At any rate, this seems to have been Johnson's main—if not only—source of income through the late 1940s and early 1950s. He published five stories there in 1948, five in 1949, and then three each in 1950 and 1951. They are not very good. For the most part, they are heavily dipped in nostalgia—the old circus man is always right, new ways always lead to danger. There’s a sugar-coated patriotism to them—George Washington makes a cameo appearance in one, and is rendered mono-dimensionally.

Beyond that, the stories engage in an awful lot of telling. There are large lectures throughout. I get the sense that these were excerpted from—or inspired by—the novel Johnson was supposed to be writing on circus life, and expressed ideas that he held very dearly, and therefore not very clearly or critically.

(In 1942, Architect and Engineer noted that he was slotted to give a lecture “The American Circus.” The contents of the lecture—or if it was actually given—are unknown. Almost twelve years later, Billboard picked up a story that Johnson had written for Clarion, publication of the Al G. Barnes Ring of the Circus Model Builders. In the article, Johnson argued that the street parades associated with the coming of the circus—at least back in the day—was poised for a revival, but there would need to be changes. Horses would no longer lead them, but be replaced by elephants and other exotic beasts of burden. As well, the trains would be made of plastic, painted colorfully, and mounted with organs and performers.)

Johnson continued to publish after his run in “Blue Book,” contributing articles to the Fortean-inflected Mystic, Short Story, Short Story for Men, and The Magazine of Horror. (There are probably others, too, still yet uncatalogued.) He even sent a story to Weird Tales—a cursed story, as he was to later remember: an earlier version had been destroyed—along with the agent—during the London blitz; another version had been accepted at some magazine that then folded. As fate would have it, Weird Tales accepted Johnson's story, but also went out of business before publishing it. That was in 1954, a time that generally witnessed the passing or transformation of all the pulps.

Four years later, Johnson was of the opinion—put down in the fanzine New Frontiers—that the heyday of weird fiction was gone. Certainly, examples of it would still be published, but only his generation was blessed with magazines that provided only weird fiction.

It is tempting to see the end of Weird Tales as signaling an end of Johnson's creative outputs. The record bears that out—but then the record could be wrong, and the absence of available evidence make this seem a more definitive period.

Be that as it may, by the mid-1960s, he had moved to 2040 Franklin Street, Apartment 803, and only saw Haas occasionally, the last recorded connection between them in 1970, when they discussed the possibility of escaped circus gorillas being mistaken for Bigfoot. When R. Alain Evarts tracked him down, he did not want to talk about the past or himself. Johnson's friends reported to Evarts that he had become reclusive and obese. Rumors abounded; that he was paranoid, told stories of having no social security card, avoided paying taxes, and had moved to Salinas, California.

Not all of this is true. He did have a social security card, which he applied for in 1971, claiming he was born in 1906 (which made him eligible for benefits). Whether he was paranoid or claimed to have been an intelligence officer in World War II cannot be verified. But, he seems to have moved to Salinas. At least, there's a death certificate from there for a Robert B. Johnson, whose birth was listed as 19 August 1907 in Kentucky, and whose death was given as 26 December 1987 (the SSDI has a different date), caused by a heart attack secondary to pneumonia.

******

When Robert Johnson discovered Charles Fort is not known. But, Chapter Two was in full swing by 1948. Tiffany Thayer wrote to Eric Frank Russell, “Our San Francisco—Chapter Two—is going great guns. Meetings that last all night and so on.” Johnson, of course, was in San Francisco at the time, and should have been familiar with some of those who had an interest in matters Fortean. He was not, however, "a 'joiner,' by nature," he told Damon Knight. "And have always stubbornly refused to hold any office in the very few organizations to which I have belonged. In my judgement, it takes up too much time, for a writer; and distracts too much from his own work."

But, he must have joined relatively soon after its founding, because he was there in 1949 when Thayer came down against the Chapters.

As Johnson has it, his interest in Fort was two-fold. First, Fort provided a great number of story ideas. In 1951, he told the Berkeley, California, Elves,' Gnomes' and Little Men's Science-Fiction, Chowder and Marching Society, “It was recently proposed to form a club that would be called, 'Writers Who Have Stolen lots from Charles Fort.' The idea was dropped, however, when it was realized that such a group would include virtually every writer in the imaginative field, including many now deceased.”

Johnson was also interested in damn facts—which, as he tells it, was the cause of Chapter Two's eviction from the Fortean Society. The group dutifully collected reports of anomalous events and even gathered ice that fell on Oakland in the middle of summer. These reports they passed on to Thayer, who complained that his Society was more interested in political things ("other rebellions") than traditional damned facts. Apparently upset over the direction of the San Francisco chapter, Thayer withdrew their charter; the Bay Area Forteans resigned en masse and reconstituted themselves as Chapter Two. (Thayer told Russell that it was the Shaver Mystery more than Chapter Two which caused him to discontinue support for the Chapters.)

So upset over Thayer's direction was Johnson that he never bought any issues of Doubt and publicly complained to the Berkeley group. That complaint was later published in the groups fanzine Rhodomagnetic Digest, then reprinted in If and Anubis—indicating the continued interest in Fort among science fiction and fantasy enthusiasts.

According to Johnson's later recollections, Chapter Two continued to meet until the death of Kenneth MacNichol and Polly Lamb. He dates this as 1957 for MacNichol and 1958 for Lamb—giving Chapter Two a lifespan of nine or ten years—but his memory, as should be obvious by now, cannot always be trusted, and the official records on this matter are still unclear.

Robert Barbour Johnson’s interest in Forteana did not end with the death of Thayer’s Fortean Society. He was a consulting editor on the journal of the Society’s successor, the International Fortean Organizations Fortean Journal, at least as early as 1974. (The International Fortean Organization was established in the mid 1960s.) The Journal also mentioned a renascent Chapter Two, which probably included George Haas, as he made connections with INFO and even considered donating his Fortean material to its archives. (It’s worth noting that INFO Journal said that there was a “Chapter Two” of their society in San Francisco, just as there had been with Thayer’s organization—but evidence of this Chapter Two is hard to come by.)

How exactly he became attached to INFO is unknown, but there is some evidence worth considering. Ron and Paul Willis created INFO; they also owned a bookstore and published a science fiction magazine, Anubis. Anubis republished Johnson’s critique of Thayer, which originally ran in the Berkeley fanzine Rhodomagnetic Digest. In a letter to Damon Knight, Johnson said that he did not know how Anubis came to reprint the article, which implies he did not know the Willis brothers—but they obviously knew him. It is possible that they approached him.

The connection may also have been made through George Haas, who was aware of INFO, even as he was thinking of getting rid of his Fortean collection. When Johnson sent a letter to INFO Journal, it was Haas who provided the bibliography—suggesting a continued connection between the two men and Forteanism.

More important, for the purpose of exploring Forteanism from the 1930s to 1960, which is my subject, Johnson wrote to INFO about a controversial issue that, according to his recollections to Damon Knight, were what got Chapter Two expelled from the Fortean Society. A description of this letter was published in INFO Journal four years after Knight’s book on Fort came out—thus, 1974.

The letter and article concerned a collection of supposed “apports”—that is to say, things which were supposed to have been teleported—collected by the Stanford family and displayed at the Stanford University Museum. These apports were the subject of an article in an early issue of Fate magazine. That story prompted a response from Stanford, which claimed no such apports existed. Johnson dismissed this as the usual damning of unconventional facts—he knew that the Stanford family had been interested in spiritualism. (It was a spiritualist the Stanford family hired to contact their dead son who had materialized the apports.) And, he had seen the display himself while he was in living in San Francisco.

It’s worth noting that the Stanford University archive has material on these apports. So they did exist.

So, then, he was born in 1907. But where? All the public records give his birth as Kentucky, and Johnson himself says it was Hopkinsville, Kentucky, in Christian County, which makes some sense—both of his parents died in there. The one discordant note is the 1920 census, which gives his place of birth as Ohio. Perhaps the issue could be settled with a birth certificate? No doubt. Unfortunately, Kentucky did not keep good records before 1911, and previous searches for Johnsons in Christian County have come up blank. Ohio organized its birth records by county until 20 December 1908, and the census gives no indication what county Johnson was born in. Hopkinsville is in the far southwest corner of Kentucky, nowhere near Ohio, and so it is not even possible to check with bordering counties.

These are the problems inherent in trying to reconstruct Barbour's life. He once called himself—in homage to one of H.P. Lovecraft's stories—The Outsider. And there's a lot of truth to that. Indeed, I am not the first to go in quest of Johnson's history. R. Alain Everts did before me, and he came up with nothing. I think I've had a little more success.

His father, Robert Jefferson Johnson, was born in November 1869 to a farming family in Holmes, Mississippi, according to the 1880 census. His future wife, Mary Barbour Legrand, was born about 1865 to a farming family in Kentucky, according to the same source. I can't find them on Ancestry.com again until 1920. If Robert Barbour Johnson was born in 1907, then his father was thirty-seven and his mother forty-two. At least according to the 1920 census, he was there only child. One wonders of they had earlier families, given the relative lateness of this one. At any rate, it seems that the trio moved around a bit. They were probably in Hopkinsville, Kentucky, during Johnson's early years. They were in Louisville for the 1920 census. They were in New Orleans in 1930, according to the census (and Johnson's memories—although those seem to be quite shaky on actual dates). Robert Jefferson and Mary B. both died later in the decade, 1933 and 1934, respectively.

In the both the 1920 and 1930 census, the Johnsons were boarders in group homes. Mary B. was a housewife. Robert Jefferson worked for an unnamed railroad company, in 1920 as a claims agent and in 1930 as part of the railroad's secret service, which was responsible for preventing crimes against railroads. It was in Louisville that Johnson first encountered “Weird Tales” when he found the an issue on a newsstand near a fire station. He was an "inveterate reader" of other pulps and was turned off by Weird Tales poor production, but fell in love with the stories. “It contents! Ye Gods, its contents!”

According to Johnson, he wanted to be a writer ("among other things") at least since high school. He tried a few stories for Weird Tales—all rejected—but was otherwise more interested in journalism. Supposedly, he took journalism courses at Tulane while the family was in New Orleans, but no record of his attendance has been found (which doesn't mean he lied; it's likely a problem with the records, since it seems that Johnson never actually received a degree). He also supposedly worked for The New Orleans Item, writing stories first as a summer job and then beyond that—seeing his stories in print quickly and getting paid for them, also quickly, more rewarding than grinding out a magazine story that might not appear in print for months with payment only coming upon publication. Exact dates for this employment history are hard to nail down, first because of uncertainty surrounding Johnson's birthdate and second because his "specialty in those days" was pretending to be another age—apparently the start of a life-long habit. "I looked, talked and acted at least five years more than my age, and was able to pass as an adult without question," he said later.

While in New Orleans, he also found another love: the circus. While there, he agreed to be a press agent for a traveling circus, according to his memoir in “The Weird Tales Story.” As he recounted there, he passed through most of Canada and the U.S. during his summer stints (he was still enrolled in Tulane otherwise). Quickly bored by his duties, he “discovered a new talent, that of animal training. I was soon handling dogs, ponies, goats, horses, and even camels.” I have uncovered no confirmatory documents, which is not a surprise. Circuses performers are notoriously hard to track—circuses are where people run away to, where they go to get lost. There’s no special reason to disbelieve Johnson, and some things which give credence to his story. He was also well known for training his pet cat, "Kitty K." Clark Ashton Smith's wife, Carol, commented on it in a letter. And at the 1956 West Coast Science Fiction Conference (Westercon), Johnson's pet performed—in the words of the Oakland Tribune—“35 stunts you wouldn't normally expect a cat to do. Unless it was Jueles Verne's cat.” He wrote about circuses often for the pulpish magazine Blue Book throughout the 1940s and 1950s, as well as a few articles for some smaller magazines. Here's a probably incomplete bibliography, from the FictionMags Index:

# The Big Hitch Blue Book Feb 1948

# Animal Man Blue Book Apr 1948

# Elephant Boss Blue Book Aug 1948

# White Horse Pioneers Blue Book Nov 1948

# Lion-Tamer Blue Book Dec 1948

# Parade Wagon Blue Book Feb 1949

# The Man Who Didn’t Like Dogs Blue Book Apr 1949

# Buffalo Bill Holds Five Kings Blue Book Jun 1949

# Truck Show Bull Blue Book Aug 1949

# Liberty Horse Blue Book Dec 1949

# Grift Show Parade Blue Book Apr 1950

# The Big Herd Blue Book Jul 1950

# Zebra Team Blue Book Dec 1950

# King of the Cage Blue Book May 1951

# Longneck Blue Book Jul 1951

# John Robinson Rides Four Blue Book Dec 1951

# Killer Lion Short Stories Dec 1958

# The Clown Short Stories for Men Aug 1959

But even if—and it's only a slight if—Johnson never joined the circus but only invented these tales, it is nonetheless true that the circus world meshed with his continued interest in the fantastic. He met someone, he said, for example, who planned to hunt for the Sasquatch at a time when the creature was not well known outside the confines of Canada. And in a world of actual freaks, the weird stories he favored seemed a lot more plausible.

According to Johnson, he quit the circus in New York, tried to live in New York City but fled the winter and went home again to New Orleans before heading to San Francisco, drawn by its literary and artistic communities. He says he left the Big Easy for the City by the Bay in 1931, but the 1930 census puts him in San Francisco already, living in a group house on Fifth Street, his job listed as essayist. In time, he would move to what he called an “artist's shack” at 1443 Montgomery Street in Telegraph Hill, not far from where Coit Tower was built in 1933. He lived in a basement apartment, but when he came out, Johnson would have been able to track the building of the Oakland-San Francisco Bay Bridge from his street.

This was a critical time in Johnson's life, but it's difficult to get an exact handle on it. It seems clear that he came to San Francisco to make his artistic mark, and in his remembrances for “The Weird Tales Story” he tells of meeting some of The City's leading literary lights—John Steinbeck, William Saroyan, Herb Caen. R. Alain Evarts, however, contacted Caen much later, and the newspaper columnist had no memory of Johnson. As well, some of Johnson's recollections just don't ring true. He said that he was welcomed into the literary circle in part because he had read every issue of Weird Tales and corresponded with the editor, he was considered an expert on the magazine—at a time when "every celebrated author in town was trying to get a story into it; and most of them had failed.” It's hard to believe Steinbeck, Saroyan, or Caen were trying to break into Weird Tales, which calls into question a lot of Johnson's memories of the time.

Apparently, Johnson lived alone during his time in San Francisco, but for his cat(s?). In an article for the fanzine New Frontiers Johnson wrote, “I am as interested in sex as the next man,” but he never married, and I've come across no evidence that he had girlfriends. That doesn't mean he didn't have any girlfriends, but his lifelong bachelorhood—like George Haas’s--certainly raises question about his sexuality. That may also explain his feeling of being an outsider. Still, he did find a community of sorts. At some point, he met up with George Haas and, through him, Clark Ashton Smith, and Smith's wife, Carol. He also knew Anton LaVey, who would later found the Church of Satan. (Through a church administrator, LaVey told Everts that he had known Johnson since 1947, when both were in the circus. That's obviously wrong—but then LaVey is known to have fabricated parts of his past when it suits him.) He seems to have been an important part of the 1956 Westercon—and that might help explain Johnson’s recollections.

The San Francisco Bay Area—San Francisco and its suburbs, Oakland, Berkeley, Palo Alto, maybe stretching the definition enough to include the Monterey Peninsula—was a hotbed for science fiction and fantasy writing in the years around World War II. Perhaps, then, he inflated the literary merit of this welcoming community by combining them with Steinbeck and Saroyan in his memories. (That's not to say some of the science fiction writers—including Anthony Boucher and Philip K. Dick were not excellent authors or, in Boucher's case, editors, but their fame is not that of Steinbeck’s.) Certainly, the pulp writer Garen Drussai has fond recollections of Johnson, and Clark Ashton Smith's wife also wrote warmly of him. It's possible, given his background, he had some of the Southerner's charm.

That Robert Johnson Barbour sometimes wrote for Weird Tales's sordid sisters (pseudonymously, of course) did not mean that he was too intimidated to write for it. "Lead Soldiers" appeared in the December 1935 issue, followed by "They" in January 1936, and "Mice" in November of that year. Johnson, though, remembers the publication history differently, writing that "They" was both the first accepted and published—which is interesting given what I think is its resonance in the San Francisco Fortean community. According to Johnson, he based the . . . well, let's call it tale . . . on “a peculiar glen I had discovered down the Peninsula, with a strangely unpleasant atmosphere." The tale, in Johnson's accounting, "had neither characters, action or plot; but it was definitely weird.” I suspect that this is the same glen that came up in conversation between George Haas and Clark Ashton Smith's wife. Haas seems to have asked her about such a place near Pacific Grove, where the Smith's were living, and she responded:

“George, I found your ‘magnetic field’ as Hazel Dreis calls it, tho she says: Near San Luis Obispo . . . . She has been there not once but twice with friends.” Hazel Dreis did not feel any sense of oppresion, as Haas (and Johnson?) did—that she experienced near Pt. Lobos, which Smith also had sensed. Rather, the glen made her feel “magnetized" and her legs “tingle.”

This sense that the world had uncanny places was central to Weird Tales (and influenced the development of Forteanism in the San Francisco Bay Area). And so it's not necessarily surprising—but it is a testament to his skill—that "They" was well-received by readers of Weird Tales. Johnson's other two stories also provoked fan mail, "Lead Soldiers" even prompting H.P. Lovecraft to write a congratulatory note.

But despite the accolades, Johnson continued to feel "always the Outsider." He thought that the editor of Weird Tales, Farnsworth Wright, didn't like him. Wright, he complained, never wrote a personal note of acceptance, always said that the stories would need careful editing (although according to Johnson nothing was changed), and perpetually complained that a page was missing from Johnson's story—which is either an eccentricity on Wright's part, or something like paranoia on Johnson's. After "Mice," Johnson had two articles rejected; these, he said, were perfectly good—one was later sold to Weird Tales—but reflected Wright's dislike for Johnson. (In fact, Wright was famous for his idiosyncratic rejections.) And so he stopped publishing there for a few years.

It may be that this is when Johnson started publishing for Rogers Terrill’s magazines; or maybe he made his money some other way. Perhaps he was a frequent contributor to the pulps; but none of his remembrances indicate this, and so suggests both the kind of writer he was as well as raising some questions about his livelihood.

Some Weird Tales writers are best understood as literary snobs. H.P. Lovecraft hated the idea of writing for money—it sullied the art. There was some of this attitude in Clark Ashton Smith. Others, such as E. Hoffman Price—another Bay Area fantasy writer and Fortean (kind of)—were professional writers. They paid attention to markets, understood what editors wanted, and created that, selling hundreds of stories over the course of their lifetime. Johnson, it seems, at least from the bibliography that now exists, was of the former type. Unknown is how he made a living. Hoffman sold enough stories to live; Smith supplemented his literary and artistic endeavors with manual labor. What did Johnson do?

He claims that his paintings sold well enough to keep him in food and clothes, as did writings for local art publications—although he doesn't say which one. He also wrote a book on Golden Gate Park—The Magic Park—but that wasn't published until 1940, so hardly could account for an income in the late 1930s. And so the question remains: What did Johnson do?

Whatever else Johnson was up to in the 1930s, he says that he drifted to San Diego for a time—there's no record of this, but also no reason to disbelieve him—and, while there, started writing for Weird Tales again, producing a letter for the May 1939 issue and three stories, "Lupa," "Silver Coffin," and "Far Below." “Lupa" included a nude scene in hopes that it would make the cover—Weird Tales's covers at the time featured nudes. Apparently, it was acceptable to finesse a nude scene into a story for Weird Tales, by Johnson's reckoning, but not so much for Terror Tales. "Far Below" was an homage to H.P. Lovecraft, was once named as the best story printed in Weird Tales, and was widely anthologized. ("The Silver Coffin" was also anthologized.)

That ended Johnson's association with Weird Tales (but not weird tales), with "Lupa" appearing in January 1941 (by which time Farnsworth Wright was no longer editor, part of a series of cost-cutting measures that also led to a decline in quality).

In 1940, he published his The Magic Park, about the Golden Gate Park.

He was drafted into the US Army as a private on 6 November 1942 (Serial Number: 39112693). According to his enlistment record, he was back in San Francisco at the time and gave his birthdate as 1905—making him 37 rather than his (actual?) 35. If it wasn't a mistake, why he would give a wrong age is not clear. According to Dan Sebby, Director and Curator of the California State Military Museum in Sacramento, the unit to which Johnson was assigned (Service Command Unit (SCU) 1952) was the permanent garrisoning party stationed at Fort Rosecrans, and so Johnson would have been involved not with the artillery batteries that were stationed at the Fort but to housekeeping services.

****

After the War, Johnson returned to his basement apartment at 1443 Montgomery—at least that's what Don Herron's timeline would have—and resumed his literary life. Not that he took care of his books. Again according to Herron, the first thing he did with a new book was break its spine so that it was easier to read. And George Haas once discovered that he had been using a slice of bacon (!) as a bookmark. He made miniature circus dioramas, and was mentioned in the novel "Laughter on the Hill," about the dissolute lifestyle among Bohemians and ex-soldiers in San Francisci during and just after the war.

In the late 1940s, he signed a contract with Blue Book magazine for six circus stories and novellas each year. He wrote in The Weird Tales Story that he made "ten times" as much as he did for any of his weird writing. At the time, Weird Tales paid about 1.5 cents per word for stories. According to Paul Reynolds's The Middle Man, Blue Book was paying about 7.5 cents per word—not quite ten times as much, but still a substantial increase.

Blue Book, at the time, was filling a niche between the pulps and the slicks such as Redbook and Saturday Evening Post, offering quality fiction at a lower cost and open to lesser known authors than those magazines. Its competitor was Argosy. Argosy was one of the first pulps; it had declined seriously by the end of the 1930s and was purchased by Popular Publications—the upstart company where Rogers Terrill worked. Eventually, he was given command of that magazine and raised its quality—surprising given his earlier interest in the sexploitation pulps. One wonders whether Johnson did not avoid Argosy because of his past associations with Terrill.

At any rate, this seems to have been Johnson's main—if not only—source of income through the late 1940s and early 1950s. He published five stories there in 1948, five in 1949, and then three each in 1950 and 1951. They are not very good. For the most part, they are heavily dipped in nostalgia—the old circus man is always right, new ways always lead to danger. There’s a sugar-coated patriotism to them—George Washington makes a cameo appearance in one, and is rendered mono-dimensionally.

Beyond that, the stories engage in an awful lot of telling. There are large lectures throughout. I get the sense that these were excerpted from—or inspired by—the novel Johnson was supposed to be writing on circus life, and expressed ideas that he held very dearly, and therefore not very clearly or critically.

(In 1942, Architect and Engineer noted that he was slotted to give a lecture “The American Circus.” The contents of the lecture—or if it was actually given—are unknown. Almost twelve years later, Billboard picked up a story that Johnson had written for Clarion, publication of the Al G. Barnes Ring of the Circus Model Builders. In the article, Johnson argued that the street parades associated with the coming of the circus—at least back in the day—was poised for a revival, but there would need to be changes. Horses would no longer lead them, but be replaced by elephants and other exotic beasts of burden. As well, the trains would be made of plastic, painted colorfully, and mounted with organs and performers.)

Johnson continued to publish after his run in “Blue Book,” contributing articles to the Fortean-inflected Mystic, Short Story, Short Story for Men, and The Magazine of Horror. (There are probably others, too, still yet uncatalogued.) He even sent a story to Weird Tales—a cursed story, as he was to later remember: an earlier version had been destroyed—along with the agent—during the London blitz; another version had been accepted at some magazine that then folded. As fate would have it, Weird Tales accepted Johnson's story, but also went out of business before publishing it. That was in 1954, a time that generally witnessed the passing or transformation of all the pulps.

Four years later, Johnson was of the opinion—put down in the fanzine New Frontiers—that the heyday of weird fiction was gone. Certainly, examples of it would still be published, but only his generation was blessed with magazines that provided only weird fiction.

It is tempting to see the end of Weird Tales as signaling an end of Johnson's creative outputs. The record bears that out—but then the record could be wrong, and the absence of available evidence make this seem a more definitive period.

Be that as it may, by the mid-1960s, he had moved to 2040 Franklin Street, Apartment 803, and only saw Haas occasionally, the last recorded connection between them in 1970, when they discussed the possibility of escaped circus gorillas being mistaken for Bigfoot. When R. Alain Evarts tracked him down, he did not want to talk about the past or himself. Johnson's friends reported to Evarts that he had become reclusive and obese. Rumors abounded; that he was paranoid, told stories of having no social security card, avoided paying taxes, and had moved to Salinas, California.

Not all of this is true. He did have a social security card, which he applied for in 1971, claiming he was born in 1906 (which made him eligible for benefits). Whether he was paranoid or claimed to have been an intelligence officer in World War II cannot be verified. But, he seems to have moved to Salinas. At least, there's a death certificate from there for a Robert B. Johnson, whose birth was listed as 19 August 1907 in Kentucky, and whose death was given as 26 December 1987 (the SSDI has a different date), caused by a heart attack secondary to pneumonia.

******

When Robert Johnson discovered Charles Fort is not known. But, Chapter Two was in full swing by 1948. Tiffany Thayer wrote to Eric Frank Russell, “Our San Francisco—Chapter Two—is going great guns. Meetings that last all night and so on.” Johnson, of course, was in San Francisco at the time, and should have been familiar with some of those who had an interest in matters Fortean. He was not, however, "a 'joiner,' by nature," he told Damon Knight. "And have always stubbornly refused to hold any office in the very few organizations to which I have belonged. In my judgement, it takes up too much time, for a writer; and distracts too much from his own work."

But, he must have joined relatively soon after its founding, because he was there in 1949 when Thayer came down against the Chapters.

As Johnson has it, his interest in Fort was two-fold. First, Fort provided a great number of story ideas. In 1951, he told the Berkeley, California, Elves,' Gnomes' and Little Men's Science-Fiction, Chowder and Marching Society, “It was recently proposed to form a club that would be called, 'Writers Who Have Stolen lots from Charles Fort.' The idea was dropped, however, when it was realized that such a group would include virtually every writer in the imaginative field, including many now deceased.”

Johnson was also interested in damn facts—which, as he tells it, was the cause of Chapter Two's eviction from the Fortean Society. The group dutifully collected reports of anomalous events and even gathered ice that fell on Oakland in the middle of summer. These reports they passed on to Thayer, who complained that his Society was more interested in political things ("other rebellions") than traditional damned facts. Apparently upset over the direction of the San Francisco chapter, Thayer withdrew their charter; the Bay Area Forteans resigned en masse and reconstituted themselves as Chapter Two. (Thayer told Russell that it was the Shaver Mystery more than Chapter Two which caused him to discontinue support for the Chapters.)

So upset over Thayer's direction was Johnson that he never bought any issues of Doubt and publicly complained to the Berkeley group. That complaint was later published in the groups fanzine Rhodomagnetic Digest, then reprinted in If and Anubis—indicating the continued interest in Fort among science fiction and fantasy enthusiasts.

According to Johnson's later recollections, Chapter Two continued to meet until the death of Kenneth MacNichol and Polly Lamb. He dates this as 1957 for MacNichol and 1958 for Lamb—giving Chapter Two a lifespan of nine or ten years—but his memory, as should be obvious by now, cannot always be trusted, and the official records on this matter are still unclear.

Robert Barbour Johnson’s interest in Forteana did not end with the death of Thayer’s Fortean Society. He was a consulting editor on the journal of the Society’s successor, the International Fortean Organizations Fortean Journal, at least as early as 1974. (The International Fortean Organization was established in the mid 1960s.) The Journal also mentioned a renascent Chapter Two, which probably included George Haas, as he made connections with INFO and even considered donating his Fortean material to its archives. (It’s worth noting that INFO Journal said that there was a “Chapter Two” of their society in San Francisco, just as there had been with Thayer’s organization—but evidence of this Chapter Two is hard to come by.)

How exactly he became attached to INFO is unknown, but there is some evidence worth considering. Ron and Paul Willis created INFO; they also owned a bookstore and published a science fiction magazine, Anubis. Anubis republished Johnson’s critique of Thayer, which originally ran in the Berkeley fanzine Rhodomagnetic Digest. In a letter to Damon Knight, Johnson said that he did not know how Anubis came to reprint the article, which implies he did not know the Willis brothers—but they obviously knew him. It is possible that they approached him.

The connection may also have been made through George Haas, who was aware of INFO, even as he was thinking of getting rid of his Fortean collection. When Johnson sent a letter to INFO Journal, it was Haas who provided the bibliography—suggesting a continued connection between the two men and Forteanism.

More important, for the purpose of exploring Forteanism from the 1930s to 1960, which is my subject, Johnson wrote to INFO about a controversial issue that, according to his recollections to Damon Knight, were what got Chapter Two expelled from the Fortean Society. A description of this letter was published in INFO Journal four years after Knight’s book on Fort came out—thus, 1974.

The letter and article concerned a collection of supposed “apports”—that is to say, things which were supposed to have been teleported—collected by the Stanford family and displayed at the Stanford University Museum. These apports were the subject of an article in an early issue of Fate magazine. That story prompted a response from Stanford, which claimed no such apports existed. Johnson dismissed this as the usual damning of unconventional facts—he knew that the Stanford family had been interested in spiritualism. (It was a spiritualist the Stanford family hired to contact their dead son who had materialized the apports.) And, he had seen the display himself while he was in living in San Francisco.

It’s worth noting that the Stanford University archive has material on these apports. So they did exist.