Another Fortean bookseller—although not much of a Fortean, at that.

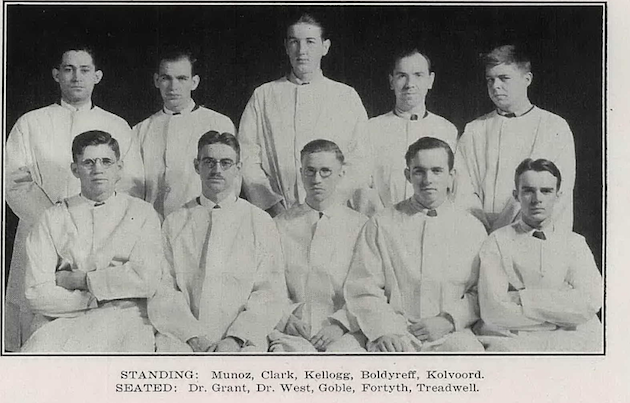

Rense A. “Robert” or “Bob” Kolvoord was born on 1 February 1907 in Battle Creek, Michigan. His father, Albert, born in Iowa to parents from Michigan, worked as a printer. His mother, Jennie (Hookstrah), born a Michiganer, had given birth to three children by 1910: Anna in 1906, Rense, and Dorothy in 1908. Both parents were about twenty one when they married at the very end of 1904. When the Great War broke out, the family was still in Michigan, Albert a painter (I’ve looked very hard at the 1910 census and his draft card, and although printer and painter look alike, I am sure that the records are different); he had lost the tips of the smallest two fingers on his left hand, which may have been one reason he didn’t serve. As captured by the 1920 census, the family had grown—a John H. Kolvoord had been born sometime around 1913—and Albert had changed jobs again, working as a carpenter. Nobody else at home was working. The family seemed well-off, at least comfortable, owning their home free and clear. Several neighbors, too, were carpenters, who owned their own homes, too, though these were usually mortgaged.

Rense A. “Robert” or “Bob” Kolvoord was born on 1 February 1907 in Battle Creek, Michigan. His father, Albert, born in Iowa to parents from Michigan, worked as a printer. His mother, Jennie (Hookstrah), born a Michiganer, had given birth to three children by 1910: Anna in 1906, Rense, and Dorothy in 1908. Both parents were about twenty one when they married at the very end of 1904. When the Great War broke out, the family was still in Michigan, Albert a painter (I’ve looked very hard at the 1910 census and his draft card, and although printer and painter look alike, I am sure that the records are different); he had lost the tips of the smallest two fingers on his left hand, which may have been one reason he didn’t serve. As captured by the 1920 census, the family had grown—a John H. Kolvoord had been born sometime around 1913—and Albert had changed jobs again, working as a carpenter. Nobody else at home was working. The family seemed well-off, at least comfortable, owning their home free and clear. Several neighbors, too, were carpenters, who owned their own homes, too, though these were usually mortgaged.

By 1930, and the beginning of the depression, the eldest daughter, Anna, had moved out of the family home—she married in 1925—but the other three children were still there. Albert and the youngest son, John, were doing contract work as decorators. Dorothy was in school. Rense had graduated from Battle Creek College, where he studied biology, but was not working. (John was not in school either.) Apparently, he married right around this time, Ruth Fitts, with whom he would have two children in the next ten years, Jeannie around 1930 (born in New York) and Philip around 1933 (born in Michigan). Ruth was a few years older than Rense. According to his biography in the Dictionary of American Antiquarian Bookdealers, he was a sailor, medical student, day laborer, and professional billiard player at various points during this period—all of which goes some distance toward explaining why his two children were born in very different places.

At some time during the dirty thirties, Rense left America behind and traveled to England. According to a (much) later newspaper article, he worked in the book business there, at a shop on Museum Street. That article says the bookstore was owned by his brother-in-law—which likely means Dorothy’s husband. Anna and her husband (Clarence Leonard) seem to have resided in Michigan all through the 1930s, while Dorothy took a teaching degree, taught for a time, and disappears from the records in 1933: she certainly could have married and moved to England at the time and invited over her unemployed brother. Whatever the case, Rense returned to America in 1936, arriving in Boston from Liverpool. By 1937, according to city directories, he was back in New Hampshire, working for a manufacturing company.

By 1939, he started dealing in books. (That news article dated the beginning of his book business in New Hampshire to 1941.) He started by selling the books from his home—maybe in Vermont, maybe in New Hampshire, records differ. For whatever reason, I cannot find a World War II draft card on Rense. The 1940s saw both of his parents pass, Albert in 1943, Jennie in 1947. Ruth’s mother died in 1948. (Her father would live into the 1960s.) In the fall of 1943, he bought the Old Settler Bookshop, which served as a home and place of business. This was in Walpole, New Hampshire. Four years later, he would be joined in the city by John Davenport Crehore, another Fortean who was in a similar business: procuring periodicals. It is most likely they knew each other, although I have no proof of it.

Over the next forty-plus years, Kolvoord would come to be a well-know institution, both in Walpole and in the bookdealing business generally. At some point, he started going by the name Robert or, less formally, Bob. His stock ranged from 40,000 to 80,000 volumes, much of it diverse, although with an emphasis on American history and tomes focused on Vermont and New Hampshire. He did a lot of business with college and university libraries and became expert at appraising books and prints. He worked closely with retiring Dartmouth faculty and at one point acquired all “the major literary journals of twentieth-century America in complete and unbound runs,” The Paris Review, Hudson Review, Partisan Review, Antioch Review, Virginia Quarterly Review, Yale Review, and others.

The family seems to have been comfortable enough. Philip attended Walpole High School, then matriculated at the University of Virginia. He became a lawyer, marrying Edith Belden in 1960. They lived in Vermont. Life for Jeanne seems to have been a bit more dramatic—albeit this is from a view far away in place and time, unable to capture the texture of the day-to-day. In 1943, the year her father opened his shop, she and a friend seem to have run away from home, according to newspaper reports, leaving notes that were not described. She married young: in 22 September 1948, she gave born to a son, Thomas. Her husband was Paul R. Galloway, an electrician and plumber. Given the mores of the time, she likely did not attend college or work, at least not until much later in life: in the 1980s she was a Vermont realtor.

As with another Fortean-associated bookseller—Ben Abrams—Kolvoord did most of his business by mail, issuing five to six catalogs each year. His store was open, though, to the public, and, by accounts, Kolvoord was popular. He was a natural raconteur, with a fondness for martinis, cigars, and talks about the book business. Kolvoord was a long-time member of the Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association, traveled for lectures, and read a lot of what he collected (before selling it again). Ruth helped him in his business but, according to one source, while lovely she was frail. She passed away in 1972, a month and a half shy of her 69th birthday; his daughter, Jeanne would die in 1981. Kolvoord continued working in the business, until his own death, when the rest of the family closed the business and sold its stock.

Rense “Bob” Albert Kolvoord died 10 November 1987 in Walpole.

It is not clear to me what brought Kolvoord to Fort or the Fortean Society. In 1938, he did publish Wonders of the World: A Guide Book, which title has a Fortean flavor, but the text is very conventional. In it, Kolvoord surveyed various wonders of the world, including those from ancient times which have since been lost, but also focusing on new ones such as streamlined trains and the George Washington Bridge. His descriptions were all deferential to official knowledge, especially scientific knowledge, which he credited as the source of many of the wonders. The closest he came to discussing alternative forms of knowledge was an oblique reference to Lemuria or Mu in a passage on Easter Island—from which he immediately backtracks, citing modern oceanography as dispelling the possibility of a vanished Pacific island. Indeed, he spent time lauding the soon-to-be-opened Palomar Observatory, which would be a butt of Thayer’s Fortean Society.

He only gets one mention in Doubt, and that one a passing reference. In issue 16 (January 1947), Thayer notes that Vermont is a “nest of Forteans,” and gives as examples Scott Nearing (who really did live in Vermont), the Crehores, and R. Kolvoord—the latter of whom all lived in Walpole, New Hampshire. True enough that Walpole was close to Vermont, but if any news publication had made a similar claim, Thayer would have pounced on the inexactitude of the statement.

That reference apparently prompted a query from one of the more diligent Forteans, Don Bloch, a bookseller, who donated his Fortean correspondence to the New York Public Library. Unfortunately, the collection only includes incoming letters, not what Bloch himself wrote. In a 21 May 1947 letter, Thayer replied, “Sure, Kolvoord is a Fortean from way back. I buy quite a lot from him.” The connection that probably attracted Bloch to Kolvoord was the book business. But how Thayer became connected to Kolvoord—and why he would have (likely) invited him to join the Society—and why Kolvoord would have joined—“way back” in the day. Well, all that remains mysterious.

The most likely connection is the Walpole one. While Rense and Thayer certainly could have met each other in New York during the early 1930s, this seems a stretch: New York is a big city. More likely, John Davenport Crehore was aware of the Fortean Society both through his uncle and his own work in collecting periodicals. It seems entirely possible that Crehore the younger could have made the connection between Kolvoord and Thayer or Kolvoord and the Society. All that is speculation, though, and the real story will remain untold.

At some time during the dirty thirties, Rense left America behind and traveled to England. According to a (much) later newspaper article, he worked in the book business there, at a shop on Museum Street. That article says the bookstore was owned by his brother-in-law—which likely means Dorothy’s husband. Anna and her husband (Clarence Leonard) seem to have resided in Michigan all through the 1930s, while Dorothy took a teaching degree, taught for a time, and disappears from the records in 1933: she certainly could have married and moved to England at the time and invited over her unemployed brother. Whatever the case, Rense returned to America in 1936, arriving in Boston from Liverpool. By 1937, according to city directories, he was back in New Hampshire, working for a manufacturing company.

By 1939, he started dealing in books. (That news article dated the beginning of his book business in New Hampshire to 1941.) He started by selling the books from his home—maybe in Vermont, maybe in New Hampshire, records differ. For whatever reason, I cannot find a World War II draft card on Rense. The 1940s saw both of his parents pass, Albert in 1943, Jennie in 1947. Ruth’s mother died in 1948. (Her father would live into the 1960s.) In the fall of 1943, he bought the Old Settler Bookshop, which served as a home and place of business. This was in Walpole, New Hampshire. Four years later, he would be joined in the city by John Davenport Crehore, another Fortean who was in a similar business: procuring periodicals. It is most likely they knew each other, although I have no proof of it.

Over the next forty-plus years, Kolvoord would come to be a well-know institution, both in Walpole and in the bookdealing business generally. At some point, he started going by the name Robert or, less formally, Bob. His stock ranged from 40,000 to 80,000 volumes, much of it diverse, although with an emphasis on American history and tomes focused on Vermont and New Hampshire. He did a lot of business with college and university libraries and became expert at appraising books and prints. He worked closely with retiring Dartmouth faculty and at one point acquired all “the major literary journals of twentieth-century America in complete and unbound runs,” The Paris Review, Hudson Review, Partisan Review, Antioch Review, Virginia Quarterly Review, Yale Review, and others.

The family seems to have been comfortable enough. Philip attended Walpole High School, then matriculated at the University of Virginia. He became a lawyer, marrying Edith Belden in 1960. They lived in Vermont. Life for Jeanne seems to have been a bit more dramatic—albeit this is from a view far away in place and time, unable to capture the texture of the day-to-day. In 1943, the year her father opened his shop, she and a friend seem to have run away from home, according to newspaper reports, leaving notes that were not described. She married young: in 22 September 1948, she gave born to a son, Thomas. Her husband was Paul R. Galloway, an electrician and plumber. Given the mores of the time, she likely did not attend college or work, at least not until much later in life: in the 1980s she was a Vermont realtor.

As with another Fortean-associated bookseller—Ben Abrams—Kolvoord did most of his business by mail, issuing five to six catalogs each year. His store was open, though, to the public, and, by accounts, Kolvoord was popular. He was a natural raconteur, with a fondness for martinis, cigars, and talks about the book business. Kolvoord was a long-time member of the Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association, traveled for lectures, and read a lot of what he collected (before selling it again). Ruth helped him in his business but, according to one source, while lovely she was frail. She passed away in 1972, a month and a half shy of her 69th birthday; his daughter, Jeanne would die in 1981. Kolvoord continued working in the business, until his own death, when the rest of the family closed the business and sold its stock.

Rense “Bob” Albert Kolvoord died 10 November 1987 in Walpole.

It is not clear to me what brought Kolvoord to Fort or the Fortean Society. In 1938, he did publish Wonders of the World: A Guide Book, which title has a Fortean flavor, but the text is very conventional. In it, Kolvoord surveyed various wonders of the world, including those from ancient times which have since been lost, but also focusing on new ones such as streamlined trains and the George Washington Bridge. His descriptions were all deferential to official knowledge, especially scientific knowledge, which he credited as the source of many of the wonders. The closest he came to discussing alternative forms of knowledge was an oblique reference to Lemuria or Mu in a passage on Easter Island—from which he immediately backtracks, citing modern oceanography as dispelling the possibility of a vanished Pacific island. Indeed, he spent time lauding the soon-to-be-opened Palomar Observatory, which would be a butt of Thayer’s Fortean Society.

He only gets one mention in Doubt, and that one a passing reference. In issue 16 (January 1947), Thayer notes that Vermont is a “nest of Forteans,” and gives as examples Scott Nearing (who really did live in Vermont), the Crehores, and R. Kolvoord—the latter of whom all lived in Walpole, New Hampshire. True enough that Walpole was close to Vermont, but if any news publication had made a similar claim, Thayer would have pounced on the inexactitude of the statement.

That reference apparently prompted a query from one of the more diligent Forteans, Don Bloch, a bookseller, who donated his Fortean correspondence to the New York Public Library. Unfortunately, the collection only includes incoming letters, not what Bloch himself wrote. In a 21 May 1947 letter, Thayer replied, “Sure, Kolvoord is a Fortean from way back. I buy quite a lot from him.” The connection that probably attracted Bloch to Kolvoord was the book business. But how Thayer became connected to Kolvoord—and why he would have (likely) invited him to join the Society—and why Kolvoord would have joined—“way back” in the day. Well, all that remains mysterious.

The most likely connection is the Walpole one. While Rense and Thayer certainly could have met each other in New York during the early 1930s, this seems a stretch: New York is a big city. More likely, John Davenport Crehore was aware of the Fortean Society both through his uncle and his own work in collecting periodicals. It seems entirely possible that Crehore the younger could have made the connection between Kolvoord and Thayer or Kolvoord and the Society. All that is speculation, though, and the real story will remain untold.