Ray Jurgen. Perhaps Jürgen. He’s mentioned in Doubt once—#15, January 1947. At the time, he was living at 32-12 54th Street, Woodside, Long Island New York. We know from what was reported by Tiffany Thayer that he was involved in horse racing—and as it happens, his house was only about fifteen miles from the Belmont Park Race Track.

Searching for Ray Jurgen’s associated with horse racing reveals that this Ray Jurgen lived in Chicago around 1930. We can be fairly certain it’s the same one, since at the time he was advertising a winning system that sounds like the one discussed by Thayer. So we have two biographical points. What can be discovered from these? As it turns out, not much: not much at all.

A good start, maybe? Except it never goes beyond there. I cannot find him in the 1940 census. Or the 1920 census. I can find no immigration records for him, no list of him among Illinois lawyers. I cannot find him in the city directories for either Chicago or New York. Newspapers-dot-com doesn’t point me toward any information. This failure is mine. There’re records somewhere. I just cannot find them. I don’t even know if the Ray Jurgen in the 1930 census is the same guy that wrote into the Fortean Society.

I can tracks the horse-racing aficionado Ray Jurgen a little bit through his publications, though. I have not been able to look at any of these, because they are scarce and expensive, and its simply not worth it. They may offer more biographical insight; I don’t know. But here’s what I can get by following the races.

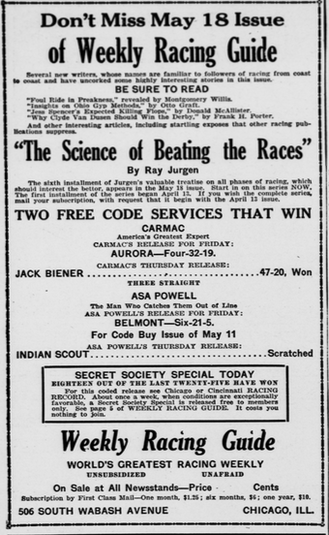

Starting in the 13 April 1929 issue, Ray Jurgen published a series of articles in Weekly Racing Guide titled ‘The Science of Beating the Races,” which was described in Kentucky-based Daily Racing Form—where the series was advertised in April and May—as “A series of articles dealing with all phases of racing, from a bettor’s standpoint.” The magazine bragged—in the same advertisement—“Since this remarkable series has been appearing, WEEKLY RACING GUIDE has received hundreds of letters praising the methods of selecting winners set forth by Mr. Jurgen.” These were collected and published as a small book in 1929 under the same title. A year later, Ray Jurgen copyrighted “The Only Way,” which was also published by Racing World, and which may have been an update or second edition.

By 1935, he seems to have become editor of a magazine, “Horse and Jockey,” which was being put out monthly from Chicago. I have not been able to find this magazine listed in WorldCat. But a biography of the writer Irving Wallace notes that he made his first sale to this magazine, an article on horse racing oddities. It was listed in “The Author & the Journalist” as well as “The Writer’s Monthly”—both of which offered potential writers descriptions of various magazines and the kind of material they wanted. The 1935 issue of “The Writer’s Monthly” reported, “Desire human-interest racing articles, about 1500 words. One short-story, about 12,000 words with the track as a background. Departments handled by specialists.” Jurgen was the editor; the magazine went for a buck-fifty.

At some point after 1935, and before 1945, Jurgen relocated to Woodside, New York, on Long Island. on 20 February of 1945 he self-published “Freedom through Horses.” I have not found it in any libraries, nor have I seen it for sale. The title suggests that it may have been an update of Jurgen’s earlier ideas, the suggestion being that if one used his system he or she could make enough money to be liberated from the drudgery of work and the everyday world.

It is possible that Jurgen later went to California. At any rate, there’s a death record for a Ray J. Jurgen in Riverside, California, who was born in another country on 1 January 1886. That Jurgen died on Christmas Eve 1963.

Jurgen appeared in Doubt once, where he was announced as a member of the Fortean Society, which implies that he may have some earlier connection with Fort, Thayer, or the Society—but the nature of that interaction is lost to history, as is much of Jurgen’s life. It’s worth considering his involvement, though, because it lights up a Fortean theme prompted by Thayer that ran against the grain of Fort’s own thoughts.

Thayer was fascinated by “cycles.” On the one hand, he worried over the constant talk of cyclical events, especially with the publication of “Cycles” by Edward R. Dewey and Edwin Dakin, which claimed to offer a “science of prediction.” As a good Fortean skeptic, Thayer thought this thesis—that everything is controlled by hidden cycles, the weather as much as economics—as under-supported by the evidence, just a new fad to justify more research spending, and a way of protecting the privileged: “It isn’t the Fat Boys who shake you down. It’s the sun.” He condemned Dewey, Deakin, and the media loveliest for cyclical theories in Doubt 21 (June 1948). Fort’s own theory of history was progressive, not cyclical—the world moving the Religious Dominant to the Scientific Dominant and now poised to enter the era of the hyphen and so stood opposed to cyclic understandings of the world.

On the other hand, though, Thayer promoted some cyclical theories—including his own. John Alden Knight’s theory of using solar and lunar cycles to guide hunting and fishing times he promoted positively. And he nursed the idea that geological history was cyclical. He imagined that the Earth went through periods when it was a sphere—and then it became a larger cube—before becoming an even larger sphere: 7 times as large, in fact. The theory explained so much, he said: why Amelia Earhart got lost (that’s why the lead article in the first issue was on her.) It explains why 7 is a sacred number, the old flat earth theories, traces of ice in the tropics, how the land masses used to fit together (explaining biogeography), earthquakes, the similarity of Mayan and Egyptian pyramids (since those two places were once close together). The Noachian Flood is the memory of the last transformation. It will happen again, Thayer thinks, and the chaos gives him pleasant dreams. The theorizing is un-Fortean in offering a real alternative science—something Thayer criticized others for doing—and also for asserting not a progressive history but a repetitive one.

It is Thayer’s fascination with cycles that makes Jurgen’s ideas worth noting, given I have found so little on him or his theories specifically, and certainly on his connection to Fort, which is a giant black box. As mentioned, Thayer took up Jurgen’s ideas in Doubt 16—which got him thinking about cycles. He nodded at Jurgen in his discussion of how talk of cycles “paralyzed thought” in issue 21. And his initial write-up sounded the tocsin over the new intellectual respectability go cycles. (One imagines that Spengler’s cyclical theory of history might have been both exemplary and inspirational.)

“Following Ponies

“The geegees have emotional cycles, according to a theory of MFS Ray Jurgen, a conceit not incompatible with MFS Knight’s Solunar Theory for fish-feeding and grist for the mill of the Foundation for the Study of Cycles. MFS Jurgen is not so explicit, but implication appears to be that when a nag is at the top of an emotional cycle, really ‘feeling his oats’, the gentlemen’s agreement between owners, their orders to their jockeys—bribes, drugs and gamblers notwithstanding—all go by the boards. The horse starts out to win and there’s just no holding him. Details from Ray Jurgen, 32-12 Fifty-fourth Street, Woodside, Long Island, N.Y.

Your Secretary has not risked a dime on it, and won’t, but the value of such a study is neither more nor less than that of the findings put forth by the academic group named above . . . But so far are we from decrying the use of bequests for such intellectual hoopla, that we advocate setting up branches on the site of every draft board, training 18-year-olds to the purpoce [sic] and passing out the gravy as generously as the Army did Spam.”

This ambiguity towards research spending fit with Thayer’s Perpetual Peace Plan, in which nations wasted money on science Thayer thought ridiculous rather than spending it blowing up young men. Better gambling on horses than war.