Something like a Fortean John Dee.

One might expect Richard Buckminster Fuller to fall into the category of “Forteans in name only,” as so many celebrities did—people Tiffany Thayer managed to get to sing up for the Society, even if they had no idea who Fort was, and never did anything with Fort, his ideas, or the Fortean Society again. But the story’s a bit more complicated than that.

Fuller himself is well known, at least as a name, and so the biography here will be abbreviated. There are a number of works on him, but none that I know of which have really made use of his so-called Chronofile, now housed at Stanford, in which—once he got the system rolling—Fuller was making notes on what he was doing every fifteen minutes! That might answer some questions about his Forteanism, but the small gain for the large amount of work means I have no plans to sort through it.

One might expect Richard Buckminster Fuller to fall into the category of “Forteans in name only,” as so many celebrities did—people Tiffany Thayer managed to get to sing up for the Society, even if they had no idea who Fort was, and never did anything with Fort, his ideas, or the Fortean Society again. But the story’s a bit more complicated than that.

Fuller himself is well known, at least as a name, and so the biography here will be abbreviated. There are a number of works on him, but none that I know of which have really made use of his so-called Chronofile, now housed at Stanford, in which—once he got the system rolling—Fuller was making notes on what he was doing every fifteen minutes! That might answer some questions about his Forteanism, but the small gain for the large amount of work means I have no plans to sort through it.

At any rate, Fuller was born to a relatively prominent Yankee family 12 July 1895. He followed a family tradition in entering Harvard in 1913, but was expelled; returned to the school in 1915, he was kicked out once again. Fuller did time in the navy during the Great War, and was impressed by that organizations’s bureaucratic efficiencies—it was from the Navy that he adopted the idea of a Chronofile. Married in 1917, Fuller struggled through the early 1920s, in large part because of the death of a daughter. He was also a Bohemian of sorts, drinking and apparently carousing quite a bit. With his father-in-law, he became involved with building houses—which had a personal impetus, Fuller feeling as though the poor conditions of his own house may have led young Alexandra to come down with polio.

The nadir came in 1927, when Fuller lost his job, the family had a another daughter (Allegra), won he could not support. The family was without savings, and he was spending money on his drinking. Eventually, he worked himself out of his depression, emerging with a mystical understanding of the universe. God was “The Greater Intellect,” and would allow those ideas to prosper which would be of the most benefit to society. Fuller dedicated himself to public service work and refused to promote himself. He continued in his Bohemianism—hanging with the likes of Dreiser and Thayer, who may have introduced him to Fort—and raged against big business, even as he continually was forced to seek employment from them. By the mid-1930s, though, he was drifting away from one crowd of Bohemians, including Dreiser, whom he felt were too closely associated with Communism, and looking for mental stimulation elsewhere.

In Fuller’s view, as explained by Lloyd Steven Seiden, the entire universe was comprised of energy. Humans, too, were energy—pattern integrities, in his vocabulary, meaning energetic waves that kept their shape—inhabiting their bodies for only a small time, then continuing on in a more metaphysical realm. In a cosmology that was not so different from some of the odder ones promoted by the Fortean Society—like that of Albert Page and N. Meade Layne—and thus may have been influenced by etheric theories of physics—Fuller argued that he seeming hierarchy of matter was made up of different kinds of energy that were knotted together, becoming increasingly more substantial. There’s more than a little of the “as Above, so Below” thinking that is characteristic of occult and esoteric philosophies.

This view of the universe had certain consequences. First, Fuller believed humans were still relatively primitive, not yet confronting the metaphysical parts of the universe. Second, it made both telepathy and teleportation theoretically possible—just a matter of waves moving through the ether, in either case (as best as I can make it out). It also meant that life after death was a given, though it was unclear exactly how to understand what that life would look like.

During the late 1920s and into the 1930s, Fuller had more practical ideas, too, though these have not really been picked up. He invented the Dymaxion House and Dymaxion Car, which were supposed to be light and assembled from kits. They did find some use during World War II. Fuller was also fascinated with geometry and invented a system of what might be called “sacred geometry,” that gave pride of place to the number four. During the late 1930s and into the 1940s, he published a magazine on shelters, and gave lectures. (In 1948 and 1949 he taught at Black Mountain College in North Carolina, which was one of the centers that gave birth to the Beats in the 1950s.) During this period, he also published two book, 4d Timelock in 1928 and, ten years later, Nine Chains to the Moon, which hoped that technology could create a better future for humans.

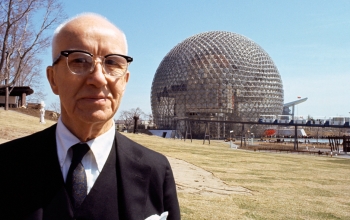

Fuller’s best known invention, The Geodesic Dome, was developed through the 1940s and patented in 1954. The Dome was seen as a symbol the future and was adopted in a number of large-scale buildings though, today, to my eye, it looks very dated: a 1950s’ vision of what the future should look like. Although Fuller kept a packed schedule, his life did become something close to more settled in the 1950s—leastwise, the struggle for existence was not so strong, comfort more at hand. (Indeed, he was becoming fat, and dieted to change that.) He became associated with Southern Illinois University Carbondale for more than a decade, which became his base of operations. He was well-known enough that he started publishing again, including poems—he was a poet of some renown. His interests expanded from housing individual families to the human family in general, and he contemplated issues of sustainability.

Fuller died 1 July 1983.

Fuller received only two mentions in the Fortean Society magazine, which again might indicate he had little connection to Fort or Fortean ideas. The first came in Doubt 15 (Summer 1946) when he was made an Honorary Life Member. This was a tribute given out by Thayer—supposedly at the instigation of the membership more broadly—that required the honoree to at least accept. In practice, it meant that Thayer wrote a letter to Fuller—though in this case I have seen no such letter—asking if he would like to be associated with the Society; Fuller would have had to say yes. And that would have buckminsterbeen that—no dues required (although in this case Fuller may have paid, since Thayer said he was “a paid up member”). Thayer would have sent issues of Doubt to Fuller, and Fuller could read them or not.

The second mention comes in the same issue, two pages on, and described Fuller’s Forteanism—as Thayer saw it—in more depth. Thayer wrote that he enjoyed Nine Chains to the Moon, although he winced at the “faith of Mr. Fuller in his jade-mistress, Science” until it became clear “that he is using the term to mean ‘technical proficiency,’ rather than ‘God,’ and that he is quite ready to forsake her the moment a more accomplished wench comes along.” He noted that there was a story about Fuller in Fortune magazine from April 1946 and another in Life “about 3 years ago.” He also noted that Fuller had published a map like the Butterfly map by BJS Cahill, which tried to show an undistorted image of the earth on a piece of paper. Fuller called his a Dymaxion Map.

That last gives some indication that Fuller’s Forteanism extended beyond what he did or did not do with the Fortean Society—that he had similar interests to other Forteans. Already there’s been hints of such overlap—in his cosmology, for example, and his friendship with the few people who were friends with Fort. It is worth noting that Fuller was also fascinated by Korzybski’s General Semantics, attended workshops by the Institute of General Semantics, gave lectures on the topic, and mentioned Korzybski in his own Synergistics. Korzybski was hobbyhorse of many Forteans, who saw him doing what Fort had done and cutting through the bullshit of language and inherited dogmas to the nut of truth.

Fuller’s respect for Fort—still uncharacterized at this point—continued into the 1960s. That was when he met a student at Southern Illinois University, Loren Coleman, who would go on to become the nation’s leading cryptozoologist and a dedicated Fortean, At the time, Coleman was looking for a way to avoid being drafted into the Vietnam War. He applied as a Conscientious Objector—and COs had been widely praised by Thayer in Doubt—getting Fuller (and Ivan Sanderson) to write him supporting letters. Coleman based his CO status on Fortean pacifism. I have not seen the letters, so I do not know what Fuller said on the matter—the story is Coleman’s—but suggests that he took Fort as a challenge to authority generally, much in the way that Thayer did.

The clearest—and latest—expression of Fuller’s Forteanism I have found is in his introduction to Damon Knight’s biography of Fort: Charles Fort: Prophet of the Unexplained. That Fuller agreed already indicates his affection for Fort. The introduction is relatively short, though, and the meat of it is at the end: indeed, the essay is best read from back, tthen beginning, and finally middle. Fuller notes that Fort is becoming popular again with the University students, who—like Fort—see that the world is more complicated than it is said to be, more worthy of love. Fuller admits that Fort’s writing is not Romantic at all, but he is a romantic at heart—which may say more about Fuller than it does Fort. For like others with a more scientific cast—I’m thinking of Maynard Shipley, especially—Fuller thinks that Fort’s collection is grand, and important, and may someday be explained by science. He says as much in the first paragraph.

The middle of the introduction is harder to make sense of. For a moment he compares Fort to George Boole, the logician, then moves on to say that somehow Fort proved publishers only publish the absurd, since he convinced a few publishers to put out his work, which was absurd. The point is not clear, and made muddier when Fuller leaves Fort altogether for the bulk of the essay, first writing about a navy man, Matthew Fontaine Moray, who instituted log-keeping rules for ships that allowed for the amassing of a great amount of data that was turned into scientific knowledge about weather—here we get a collection even more massive than Fort’s, but put to very different uses. Fuller then goes on to consider a man who took time-lapse photography in the Grand Canyon, showing that mist moved in waves—again the amassing of data for scientific ends. Which fit with Fuller’s own procedure: he emphasized imagination working on a great collections of data to derive new abstractions. But this is very far from Fort’s own era of the hyphen.

Fitting, then, that in my reconstruction of the essay it ends with Fuller’s declining memory. He admits that he doesn’t know if he ever met Fort, though he did go about town with Dreiser and Thayer. Then he attempts to set down the record of what he does know—and which seems wrong. He writes that Thayer made him an Honorary Life Member of the Society in 1938, on the occasion of Nine Chains to the Moon’s publication. Perhaps this is how it happened and it took Thayer eight years to mention it all in Doubt, but it certainly doesn’t accord with the written record.

There is a bit more to be pulled out of the essay, though not as published. Stanford University, which houses much of Fuller’s papers, has a file on his writing of the introduction. The correspondence is all strictly business, but there are several drafts, a couple of them much longer. What I am guessing is the first—because it is handwritten—confirms that Fuller saw Fort as providing grist for the scientific mill. He thought Fort appeared prematurely, his data ignored when it would have been taken up and studied. The bulk of the essay, though, is about the history of science, written in Fuller-speak that would have been impenetrable to anyone not versed in the language. It also makes Fort out to be a proponent of reincarnation, which would suggest that Fuller did not go back and read Fort before writing the introduction.

A (perhaps?) later version, dated 26 September 1969, is more in accord with the one that was eventually published, though it includes some of Fuller’s own uncanny experiences—in particular, noting the different colors of ocean water while sailing off the coast of Florida. This version noted, briefly, Fort’s Romanticism, but also took time out to mention that Fort included many terribly inaccurate reports—and that it was the job of people now to remove the distortions and get back to the nut-truth. Fuller absolved Fort of some of the blame, though, as he note that newspapers themselves were full of inaccuracies. Nonetheless, Fort made it “perfectly clear that there are very important universal events taking place that pass un-noticed.”

A draft dated 25 October 1969 opened in the same way as the handwritten draft (so maybe that draft is from later), with he short paragraph “Charles Fort is hauntingly picturable. He is also lovable,” and then going on to Fuller’s history of science, with its still- and premature births. Fort again is representative of the premature breakthrough. The essay then continues, incorporating pieces from the September draft—about the inaccuracies of newspapers, and Fort; Fuller’s experiences in the Florida waters; and then going on to name-check Boole before dwelling on Moray and the Grand Canyon videographer and ending as does the published version.

A day later comes his last, and longest draft. There is the same opening, the same history of premature discoveries, the same notion that Fort thought reincarnation probable, and then an insertion—hinted at in the handwritten draft, but not included. It’s a long exchange between José Argüelles (a New Age author) and Fuller that Fuller insists Fort would have liked: It was about the coincidence that Fuller’s system of synergy was similar to the philosophy of the French writer Charles Henry, even though Fuller had never heard of Henry. A weak kind of coincidence, then, and something that Fort might have noted, at least in passing, but not worth the two-and-half-pages of incomprehensible New Age-meets-Fuller speak. This introduction then goes on to incorporate all the other elements of the various drafts.

In the end, one comes away from all of this feeling as though Fuller had a very weak grasp on Fort and Fort’s ideas. It’s not that he was a Fortean in name only—he was interested in Fort, at least as a symbol. It’s just that his own ideas were more important to him, and he wanted to incorporate Fort into his system. Fort was a collector of facts—and apparently a proponent of reincarnation—that pointed to a more complex world, but that world could be understood scientifically, and should be done so, Fort’s facts either deemed inaccurate and tossed out or incorporated into the larger system. Fuller may have been constitutionally irritated by authority, but in the end he wanted to make a new kind of orthodoxy and thought Fort provided the data to do so.

The nadir came in 1927, when Fuller lost his job, the family had a another daughter (Allegra), won he could not support. The family was without savings, and he was spending money on his drinking. Eventually, he worked himself out of his depression, emerging with a mystical understanding of the universe. God was “The Greater Intellect,” and would allow those ideas to prosper which would be of the most benefit to society. Fuller dedicated himself to public service work and refused to promote himself. He continued in his Bohemianism—hanging with the likes of Dreiser and Thayer, who may have introduced him to Fort—and raged against big business, even as he continually was forced to seek employment from them. By the mid-1930s, though, he was drifting away from one crowd of Bohemians, including Dreiser, whom he felt were too closely associated with Communism, and looking for mental stimulation elsewhere.

In Fuller’s view, as explained by Lloyd Steven Seiden, the entire universe was comprised of energy. Humans, too, were energy—pattern integrities, in his vocabulary, meaning energetic waves that kept their shape—inhabiting their bodies for only a small time, then continuing on in a more metaphysical realm. In a cosmology that was not so different from some of the odder ones promoted by the Fortean Society—like that of Albert Page and N. Meade Layne—and thus may have been influenced by etheric theories of physics—Fuller argued that he seeming hierarchy of matter was made up of different kinds of energy that were knotted together, becoming increasingly more substantial. There’s more than a little of the “as Above, so Below” thinking that is characteristic of occult and esoteric philosophies.

This view of the universe had certain consequences. First, Fuller believed humans were still relatively primitive, not yet confronting the metaphysical parts of the universe. Second, it made both telepathy and teleportation theoretically possible—just a matter of waves moving through the ether, in either case (as best as I can make it out). It also meant that life after death was a given, though it was unclear exactly how to understand what that life would look like.

During the late 1920s and into the 1930s, Fuller had more practical ideas, too, though these have not really been picked up. He invented the Dymaxion House and Dymaxion Car, which were supposed to be light and assembled from kits. They did find some use during World War II. Fuller was also fascinated with geometry and invented a system of what might be called “sacred geometry,” that gave pride of place to the number four. During the late 1930s and into the 1940s, he published a magazine on shelters, and gave lectures. (In 1948 and 1949 he taught at Black Mountain College in North Carolina, which was one of the centers that gave birth to the Beats in the 1950s.) During this period, he also published two book, 4d Timelock in 1928 and, ten years later, Nine Chains to the Moon, which hoped that technology could create a better future for humans.

Fuller’s best known invention, The Geodesic Dome, was developed through the 1940s and patented in 1954. The Dome was seen as a symbol the future and was adopted in a number of large-scale buildings though, today, to my eye, it looks very dated: a 1950s’ vision of what the future should look like. Although Fuller kept a packed schedule, his life did become something close to more settled in the 1950s—leastwise, the struggle for existence was not so strong, comfort more at hand. (Indeed, he was becoming fat, and dieted to change that.) He became associated with Southern Illinois University Carbondale for more than a decade, which became his base of operations. He was well-known enough that he started publishing again, including poems—he was a poet of some renown. His interests expanded from housing individual families to the human family in general, and he contemplated issues of sustainability.

Fuller died 1 July 1983.

Fuller received only two mentions in the Fortean Society magazine, which again might indicate he had little connection to Fort or Fortean ideas. The first came in Doubt 15 (Summer 1946) when he was made an Honorary Life Member. This was a tribute given out by Thayer—supposedly at the instigation of the membership more broadly—that required the honoree to at least accept. In practice, it meant that Thayer wrote a letter to Fuller—though in this case I have seen no such letter—asking if he would like to be associated with the Society; Fuller would have had to say yes. And that would have buckminsterbeen that—no dues required (although in this case Fuller may have paid, since Thayer said he was “a paid up member”). Thayer would have sent issues of Doubt to Fuller, and Fuller could read them or not.

The second mention comes in the same issue, two pages on, and described Fuller’s Forteanism—as Thayer saw it—in more depth. Thayer wrote that he enjoyed Nine Chains to the Moon, although he winced at the “faith of Mr. Fuller in his jade-mistress, Science” until it became clear “that he is using the term to mean ‘technical proficiency,’ rather than ‘God,’ and that he is quite ready to forsake her the moment a more accomplished wench comes along.” He noted that there was a story about Fuller in Fortune magazine from April 1946 and another in Life “about 3 years ago.” He also noted that Fuller had published a map like the Butterfly map by BJS Cahill, which tried to show an undistorted image of the earth on a piece of paper. Fuller called his a Dymaxion Map.

That last gives some indication that Fuller’s Forteanism extended beyond what he did or did not do with the Fortean Society—that he had similar interests to other Forteans. Already there’s been hints of such overlap—in his cosmology, for example, and his friendship with the few people who were friends with Fort. It is worth noting that Fuller was also fascinated by Korzybski’s General Semantics, attended workshops by the Institute of General Semantics, gave lectures on the topic, and mentioned Korzybski in his own Synergistics. Korzybski was hobbyhorse of many Forteans, who saw him doing what Fort had done and cutting through the bullshit of language and inherited dogmas to the nut of truth.

Fuller’s respect for Fort—still uncharacterized at this point—continued into the 1960s. That was when he met a student at Southern Illinois University, Loren Coleman, who would go on to become the nation’s leading cryptozoologist and a dedicated Fortean, At the time, Coleman was looking for a way to avoid being drafted into the Vietnam War. He applied as a Conscientious Objector—and COs had been widely praised by Thayer in Doubt—getting Fuller (and Ivan Sanderson) to write him supporting letters. Coleman based his CO status on Fortean pacifism. I have not seen the letters, so I do not know what Fuller said on the matter—the story is Coleman’s—but suggests that he took Fort as a challenge to authority generally, much in the way that Thayer did.

The clearest—and latest—expression of Fuller’s Forteanism I have found is in his introduction to Damon Knight’s biography of Fort: Charles Fort: Prophet of the Unexplained. That Fuller agreed already indicates his affection for Fort. The introduction is relatively short, though, and the meat of it is at the end: indeed, the essay is best read from back, tthen beginning, and finally middle. Fuller notes that Fort is becoming popular again with the University students, who—like Fort—see that the world is more complicated than it is said to be, more worthy of love. Fuller admits that Fort’s writing is not Romantic at all, but he is a romantic at heart—which may say more about Fuller than it does Fort. For like others with a more scientific cast—I’m thinking of Maynard Shipley, especially—Fuller thinks that Fort’s collection is grand, and important, and may someday be explained by science. He says as much in the first paragraph.

The middle of the introduction is harder to make sense of. For a moment he compares Fort to George Boole, the logician, then moves on to say that somehow Fort proved publishers only publish the absurd, since he convinced a few publishers to put out his work, which was absurd. The point is not clear, and made muddier when Fuller leaves Fort altogether for the bulk of the essay, first writing about a navy man, Matthew Fontaine Moray, who instituted log-keeping rules for ships that allowed for the amassing of a great amount of data that was turned into scientific knowledge about weather—here we get a collection even more massive than Fort’s, but put to very different uses. Fuller then goes on to consider a man who took time-lapse photography in the Grand Canyon, showing that mist moved in waves—again the amassing of data for scientific ends. Which fit with Fuller’s own procedure: he emphasized imagination working on a great collections of data to derive new abstractions. But this is very far from Fort’s own era of the hyphen.

Fitting, then, that in my reconstruction of the essay it ends with Fuller’s declining memory. He admits that he doesn’t know if he ever met Fort, though he did go about town with Dreiser and Thayer. Then he attempts to set down the record of what he does know—and which seems wrong. He writes that Thayer made him an Honorary Life Member of the Society in 1938, on the occasion of Nine Chains to the Moon’s publication. Perhaps this is how it happened and it took Thayer eight years to mention it all in Doubt, but it certainly doesn’t accord with the written record.

There is a bit more to be pulled out of the essay, though not as published. Stanford University, which houses much of Fuller’s papers, has a file on his writing of the introduction. The correspondence is all strictly business, but there are several drafts, a couple of them much longer. What I am guessing is the first—because it is handwritten—confirms that Fuller saw Fort as providing grist for the scientific mill. He thought Fort appeared prematurely, his data ignored when it would have been taken up and studied. The bulk of the essay, though, is about the history of science, written in Fuller-speak that would have been impenetrable to anyone not versed in the language. It also makes Fort out to be a proponent of reincarnation, which would suggest that Fuller did not go back and read Fort before writing the introduction.

A (perhaps?) later version, dated 26 September 1969, is more in accord with the one that was eventually published, though it includes some of Fuller’s own uncanny experiences—in particular, noting the different colors of ocean water while sailing off the coast of Florida. This version noted, briefly, Fort’s Romanticism, but also took time out to mention that Fort included many terribly inaccurate reports—and that it was the job of people now to remove the distortions and get back to the nut-truth. Fuller absolved Fort of some of the blame, though, as he note that newspapers themselves were full of inaccuracies. Nonetheless, Fort made it “perfectly clear that there are very important universal events taking place that pass un-noticed.”

A draft dated 25 October 1969 opened in the same way as the handwritten draft (so maybe that draft is from later), with he short paragraph “Charles Fort is hauntingly picturable. He is also lovable,” and then going on to Fuller’s history of science, with its still- and premature births. Fort again is representative of the premature breakthrough. The essay then continues, incorporating pieces from the September draft—about the inaccuracies of newspapers, and Fort; Fuller’s experiences in the Florida waters; and then going on to name-check Boole before dwelling on Moray and the Grand Canyon videographer and ending as does the published version.

A day later comes his last, and longest draft. There is the same opening, the same history of premature discoveries, the same notion that Fort thought reincarnation probable, and then an insertion—hinted at in the handwritten draft, but not included. It’s a long exchange between José Argüelles (a New Age author) and Fuller that Fuller insists Fort would have liked: It was about the coincidence that Fuller’s system of synergy was similar to the philosophy of the French writer Charles Henry, even though Fuller had never heard of Henry. A weak kind of coincidence, then, and something that Fort might have noted, at least in passing, but not worth the two-and-half-pages of incomprehensible New Age-meets-Fuller speak. This introduction then goes on to incorporate all the other elements of the various drafts.

In the end, one comes away from all of this feeling as though Fuller had a very weak grasp on Fort and Fort’s ideas. It’s not that he was a Fortean in name only—he was interested in Fort, at least as a symbol. It’s just that his own ideas were more important to him, and he wanted to incorporate Fort into his system. Fort was a collector of facts—and apparently a proponent of reincarnation—that pointed to a more complex world, but that world could be understood scientifically, and should be done so, Fort’s facts either deemed inaccurate and tossed out or incorporated into the larger system. Fuller may have been constitutionally irritated by authority, but in the end he wanted to make a new kind of orthodoxy and thought Fort provided the data to do so.