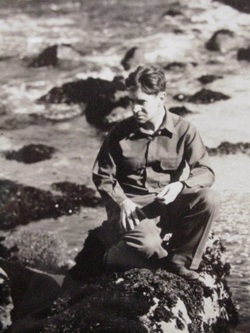

Two examples. The first comes from a letter written by Edward F. Ricketts to Don Emblem dated 3 November 1943. Ricketts was a marine biologist who developed into something of a philosophe. He is best known for his friendship and work with John Steinbeck. At the time, Ricketts was living in the Monterey area, where he was also friendly with Henry Miller and Joseph Campbell. Emblem was a poet.

Ricketts wrote, “Your speaking of Henry Miller reminds me to say that Janko met him down there, and Miller speaks of coming on here again. I think he is a good man. Charles Fort makes my tired ache, although I realize I am one of a minority. Many people whose minds I respect admire him: Janko; at one time John; Toni. Most of the writers whose work appears not to be circumscribed by form are those who have got to use it as familiarly as a person uses his senses.”

The context of the reference to Fort is not exactly clear; Emblem’s article, as far as I know, has not survived. But it seems fair to say that Emblem probably brought up the subject of Fort. The important point here is to note that in early 1940s, Fort was well-known among the Monterey-area Bohemians. In particular, Ricketts specifically references Janko—Jean Varda, a Greek painter who had been in the U.S. Since 1939. Janko and Henry Miller (another Fortean) were good friends. (At the time of the letter, though, Miller was in southern California.)

Ricketts wrote, “Your speaking of Henry Miller reminds me to say that Janko met him down there, and Miller speaks of coming on here again. I think he is a good man. Charles Fort makes my tired ache, although I realize I am one of a minority. Many people whose minds I respect admire him: Janko; at one time John; Toni. Most of the writers whose work appears not to be circumscribed by form are those who have got to use it as familiarly as a person uses his senses.”

The context of the reference to Fort is not exactly clear; Emblem’s article, as far as I know, has not survived. But it seems fair to say that Emblem probably brought up the subject of Fort. The important point here is to note that in early 1940s, Fort was well-known among the Monterey-area Bohemians. In particular, Ricketts specifically references Janko—Jean Varda, a Greek painter who had been in the U.S. Since 1939. Janko and Henry Miller (another Fortean) were good friends. (At the time of the letter, though, Miller was in southern California.)

The John in question is John Steinbeck, although apparently he had since overcome that enthusiasm. Given that this letter was written in 1943, it is quite likely that Fort came to their attention in 1941, when Tiffany Thayer arranged to have an omnibus addition of Fort’s four books published. If so, Steinbeck’s short-lived interest cam when he was writing The Sea of Cortez with Ricketts as well as The Moon is Down and Bombs Away. These latter were part of the war effort, and in 1943 he worked for the New York Herald as a war correspondent as well as the OSS.

Toni was Eleanor Susan Brownell Anthony "Toni" Solomons Jackson, Steinbeck’s secretary, with whom Ricketts had started a relationship in 1940. (They lived together until 1947 but never married.) Toni’s father had been an explorer and member of the Sierra Club.

The second example comes from Neeli Cherkovski’s book of essays about poets he has known Whitman's Wild Children: Portraits of Twelve Poets. Cherkovski is himself a poet.

He wrote, Philip “Lamantia is a brilliant conversationalist and natural teacher. . . . Ten cups of coffee and an hour later, he would still be expounding on anything from the poetic science of Charles Fort to a newly discovered theory on the location of Atlantis.”

Lamantia was a poet of the San Francisco Renaissance, probably the one most influenced by surrealism. Born in San Francisco in 1927, he published his first poem in 1943. After a brief stint in New York, his first collection, Erotic Poems, came out in 1945. Lamantia was mentored by Kenneth Rexroth (among others, of course). His obituary in the San Francisco Chronicle pithily captures the essence of his poetry:

Mr. Lamantia was a widely read, largely self-taught literary prodigy whose visionary poems—ecstatic, terror-filled, erotic—explored the subconscious world of dreams and linked it to the experience of daily life.

Cherkovski saw Fort as central to understanding Lamantia:

The previous night I had read through Charles Fort’s Book of the Damned, required reading for Lamantia. Fort describes lost planets, strange lights falling on earth from heaven, black rains, chunks of ice from the sly, and a procession of the damned. His book is actually an epic poem, one any surrealist might find especially interesting. As Lamantia talked on about Mexico [where he had experimented with Peyote in the 1950s], It sounded increasingly like a zone between reality and unreality. . . . ‘You can disappear in Mexico,’ [Lamantia] told me as I left, “like Ambrose Bierce or B. Traven.’ [Fort wrote of Bierce’s disappearance.] When I got home I found that sleep was useless. I picked up The Blood of the Air [a collection by Lamantia—note the Fortean allusion of the title] and read “I shall say these things that curl beyond reach/A fatal balloon/Resolving riddles/it’s pure abyss-cracking vortex.”

Toni was Eleanor Susan Brownell Anthony "Toni" Solomons Jackson, Steinbeck’s secretary, with whom Ricketts had started a relationship in 1940. (They lived together until 1947 but never married.) Toni’s father had been an explorer and member of the Sierra Club.

The second example comes from Neeli Cherkovski’s book of essays about poets he has known Whitman's Wild Children: Portraits of Twelve Poets. Cherkovski is himself a poet.

He wrote, Philip “Lamantia is a brilliant conversationalist and natural teacher. . . . Ten cups of coffee and an hour later, he would still be expounding on anything from the poetic science of Charles Fort to a newly discovered theory on the location of Atlantis.”

Lamantia was a poet of the San Francisco Renaissance, probably the one most influenced by surrealism. Born in San Francisco in 1927, he published his first poem in 1943. After a brief stint in New York, his first collection, Erotic Poems, came out in 1945. Lamantia was mentored by Kenneth Rexroth (among others, of course). His obituary in the San Francisco Chronicle pithily captures the essence of his poetry:

Mr. Lamantia was a widely read, largely self-taught literary prodigy whose visionary poems—ecstatic, terror-filled, erotic—explored the subconscious world of dreams and linked it to the experience of daily life.

Cherkovski saw Fort as central to understanding Lamantia:

The previous night I had read through Charles Fort’s Book of the Damned, required reading for Lamantia. Fort describes lost planets, strange lights falling on earth from heaven, black rains, chunks of ice from the sly, and a procession of the damned. His book is actually an epic poem, one any surrealist might find especially interesting. As Lamantia talked on about Mexico [where he had experimented with Peyote in the 1950s], It sounded increasingly like a zone between reality and unreality. . . . ‘You can disappear in Mexico,’ [Lamantia] told me as I left, “like Ambrose Bierce or B. Traven.’ [Fort wrote of Bierce’s disappearance.] When I got home I found that sleep was useless. I picked up The Blood of the Air [a collection by Lamantia—note the Fortean allusion of the title] and read “I shall say these things that curl beyond reach/A fatal balloon/Resolving riddles/it’s pure abyss-cracking vortex.”