“Fortean extraordinaire” or node in several Fortean nexuses?

Odo (Ode; Otto) Max Bernhard Stade was born 2 July 1892 in what was, at the time, Germany but now is part of France. My high school history teacher called these the ping-pong states, Alsace-Lorraine. It’s not fair to say that’s the last known fact about him we have—there’re plenty—but certainly his early life is difficult to document. And not from lack of material. There are both official documents and recollections. But there’s a slippage between them, an-off-set, like a misprinted newspaper, that makes it hard rehearse Stade’s precise history: for all the murkiness, there is a real history, a true succession of events.

There’s an online biography of him, Odo B. Stade, 1892-1976— A Life of Dedicated Service, which seems to have been written by his widow in the late 1980s. [Update, September 2015: The biography is not just by Maria, but also put together by Scott Rubel.] The exact provenance is unclear, and so some wariness is good. There are also newspaper accounts from the 1950s and remembrances. Even a few historical examinations. These sometimes accord with the documentary record, sometimes put meat on the biographical skeleton, sometimes, frankly, conflict. Let’s follow these lines, chary all the way. Where we end up—Fortean extraordinaire, nodes in various nexuses—Lord only knows.

Odo (Ode; Otto) Max Bernhard Stade was born 2 July 1892 in what was, at the time, Germany but now is part of France. My high school history teacher called these the ping-pong states, Alsace-Lorraine. It’s not fair to say that’s the last known fact about him we have—there’re plenty—but certainly his early life is difficult to document. And not from lack of material. There are both official documents and recollections. But there’s a slippage between them, an-off-set, like a misprinted newspaper, that makes it hard rehearse Stade’s precise history: for all the murkiness, there is a real history, a true succession of events.

There’s an online biography of him, Odo B. Stade, 1892-1976— A Life of Dedicated Service, which seems to have been written by his widow in the late 1980s. [Update, September 2015: The biography is not just by Maria, but also put together by Scott Rubel.] The exact provenance is unclear, and so some wariness is good. There are also newspaper accounts from the 1950s and remembrances. Even a few historical examinations. These sometimes accord with the documentary record, sometimes put meat on the biographical skeleton, sometimes, frankly, conflict. Let’s follow these lines, chary all the way. Where we end up—Fortean extraordinaire, nodes in various nexuses—Lord only knows.

According to to the online biography, which is the only source for his earliest life, Stade’s family was partially descended from Hungarians and he spent a lot of his childhood there. He was tutored until attending the university, where he studied philology. Seemingly a prodigy, he joined the navy in 1907—aged 15—and traveled the world until 1912 when, at the age of 20, he resigned to join the Austro-Hungarian Foreign Office, where he was assigned charge d’affaires of Mexico. Already indignant about the caste system in Hungary, Stade was supposedly shocked by the state of peonage in Mexico.

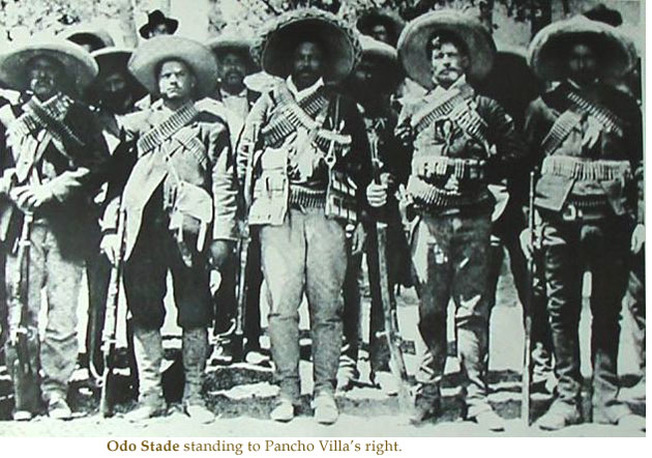

At the time, Mexico was in the midst of a revolution, whose rough chronological contours are 1910 and 1920. As most revolutions, it was a complicated affair, with many partitions. Among the revolutionary generals was Pancho Villa, who seized haciendas and gave the land to the poor. His supporters, at least in the second half of the revolution, included German officials. The biography of Stade claims that he, too, was a Villa supporter, negotiating Austro-Hungary’s exportation of gold in return for arms, which Stade helped to obtain from the United States. Stade was supposedly hurt twice, including having his knee shattered by bullets, before leaving Mexico suffering from malaria. There is a picture of Pancho Villa, with Stade to his right, but the provenance and attribution of names is uncertain.

There are several other accounts of this period in Stade’s life. Much later, living in southern California, Stade would become a father-figure to Michael Clark Rubel [NB: Edited September 2015 to correct spelling from Ruble to Rubel, et passim.]. Rubel would, even later, remember the stories that Stade told him: about how he switched boots with Villa, because Stade’s were better. And Stade bought a better pistol from Villa’s girlfriend to give to the revolutionary. And how these artifacts came into Rubel’s possession when he was just 15. According to Rubel, Stade was with Villa in 1923 when Villa was assassinated. Only Odo and another man survived the strafing by a Tommy Gun, Odo showing horrible scars on his chest much later, maybe only three, maybe only from ricochets, but bad enough to make Rubel wonder how Stade survived.

There is also a documentary record. According to U.S. Immigration papers, the 1920 census, and Stade’s 1924 application for a U.S. Passport, he reached the U.S. in August 1913 via New York. A clerk, five-foot-eight and 135 pounds, he renounced his allegiance to William II, the German Emperor on 6 January 1914. He’s in the Los Angeles City directories starting in 1914. It’s always possible that he dissembled in these records. Villa was no friend of America, having attacked Columbus, Mew Mexico in 1916. All but three of Stade’s documents post-date Villa’s split with America. The most relevant, though, does date from before this break and denies any connection to Mexico. Stade reports he traveled to New York City from Bremen, in northwest Germany.

Another problem with the timeline given by Stade’s associates is that Villa did not receive German (or Austro-Hungarian) aid before 1915, by which time Stade was living in Los Angeles and working as a manager. As well, the description of him given in his immigration papers is very different than the one offered in the biography: “His doctor recommended living in the wild, so in May of 1916 Odo hiked to Tahoe and on to the High Sierras where he lived off the land for six months. He had weighed only 108 pounds when he left for the mountains, and when he came back, he weighted 174.” For what it is worth, Stade is in the 1916 and 1917 Los Angeles City Directories, his occupation given as a clerk. (Another friend of Stade’s claimed he was working for the French government—but there is nothing in Stade’s biography to suggest he was suggest French politically, as opposed to linguistically.)

Further calling into question how much of his early life was invented, the biography credits Stade with establishing the altitude of some of the Sierra peaks during his time in the wilderness. The problem here is that the California Geological Survey had been established before Stade was even born, in 1863, and there had been extensive exploration since then. A detailed map of the Sierras was published by the U.S. Geological Service in 1912—when Stade was supposedly taking over in Mexico. I find no reference to Stade in California Geological Survey publications.

But then there’s the research of others. Historian Lawrence D. Taylor has examined the role of mercenaries in the Mexican Revolution. His 1986 paper for “The Americas” did not mention Stade. His 1993 monograph does; but it is in Spanish, published in Mexico, and difficult to come by. Supposedly, there is documentary evidence proving Stade was among the Villanistas. If, indeed, Stade aided Pancho Villa, there are multiple accounts of why he did so, and how he came to Mexico.

In addition to the online biography stating that he was an official for the (moribund) Austro-Hungary empire, there are two other stories. One, which was reported in 1959 newspapers, had him as associated with a mining company, the French concern “International Company of Mines.” That would explain his interest in exporting gold, and, indeed, these accounts focus on his mineralogical successes. He left Mexico, in this narrative, in 1915, tired from fighting and suffering from malaria. The other explanation is from Taylor, and grants Stade an official capacity. Stylized Ode B. Stade, he was referred to as consejero militar, or military counselor. At least, that was an official position with Villa, if not with other governments. Perhaps, as some have said, he was simply a mercenary, finding himself in Mexico after some time in the Austrian navy—the exact time itself of some debate. It may be that, on this account, his Mexico adventures occurred in 1910 and 1911.

The on-line biography has him meeting Adam Clark Vroman, a bookseller and photographer, shortly after arriving in California, and that seems to be true, whether he came straight from Europe or via Mexico. The 1914 Los Angeles city directory has him as a salesman for Vroman; in 1916, he was managing a different bookstore, Hollywood Bookstore. That seems to have been a short time position, though, as in 1917 he was a clerk and his registration for the draft put him as a laborer for D. W. Colby of Colby Springs—likely this means he was working in a part of the San Gabriel Mountains that became the Angeles National Forest in 1908. Here, at least, he was in the mountains.

One 1959 newspaper article—in the Pasadena “Independent Star-News”—reported he spent the years 1915 to 1918 exploring the San Gabriel mountains. Part of the reason was health. He worked for Colby. He ran mules through the mountains supplying camps. He watched the number of hikers explode. He watched the number of big horn sheep decline. He fought wildfires. He was just shy of forty years old. All of this detail, though, is retrospective, nothing from the time, and one feels that Stade was a great storyteller, perhaps given to exaggeration.

A few other bits of information from the draft registration bear notice. Stade was supporting his mother. (His father had died.) He reports that he served in the German Navy for fourteen months—no connection to the French government—where he achieved the rank of corporal—so less than the five years reported in the biography, and not a lieutenant. The registration also noted that he had no disabilities, which certainly raises questions about his knee being shot up while he was with Pancho Villa in Mexico. Or his chest. The government would have every reason to get the answer to this question correct. The draft card was signed 5 June 1917.

By 1920, he was back to managing a bookstore. Still single, Stade was a boarder with the Rentch family. Originally from West Virginia, the patriarch, Louis, was descended from a family out of Alsace-Lorraine, too. Although Stade was said to be able to read and write English, he gave his birth language as French (while his parents, he said, both spoke German). He was also supposedly attending school. Likely he was back with the Hollywood Bookstore, but his relationship with that institution is a vexed one. In 1929, he would tell the magazine “Motion Picture” that he had established it fifteen years before—which doesn’t quite fit with his employment history, albeit he had a frequent association with the place. According to the biography, he took over the managership of Hollywood Bookstore—it was owned by Frederick G. Leonard—in 1916, after his Sierra wanderings, at the urging of Vroman. Vroman died in July of 1916, which makes this story just possible.

Supposedly, Stade became associated with Hollywood in its infancy. That 1959 article had him playing bit parts in “The Miracle Man,” “Right to Happiness,” “Blind Husbands,” and “The World and Its Women.” (The Internet Movie Database does not list him among the cast members for any of these films.) This Hollywood link, supposedly, led him to Dick Grace’s “Squadron of Death,” a stunt-flying group. I can find no link between him and these flyers, beyond the much-later reports, and there is no mention of how injuries that he may have suffered with Pancho Villa affected this career.

On 28 April 1924, Stade applied for a passport. Further complicating his story of arms-dealing with Pancho Villa, he declared not only that he had arrived from Bremen in August 1913 but that he had resided in the United States for ten continuous years. His naturalization process had been completed 7 May 1920. He listed his occupation as bookstore manager—identification was provided for him by Frederick G. Leonard, who gave his occupation as banking. The two had known each other for ten years, Leonard attested, suggesting that he did own the bookstore, but Stade managed it. He reported he would travel to Britain, Germany, and Austria on business, and Czechoslavakia, France, and Hungary on pleasure. It is worth noting that the passport listed no distinguishing marks, such as a bad knee or scarred chest. He was mustachioed.

According to the on-line biography, Stade undertook the travel at the bequest of a Hollywood studio, which wanted him to conduct research for them. The 1959 newspaper report had him as a talent scout, and a perspicacious one at that. “One of the big names that Stade signed to contract on that trip was Sergei Eisenstein, Russian director of such great films as “Potemkin” and “Ten Days that Shook the World.” Eisenstein will recur in another Fortean entry, and would be connected to Mexico, but I cannot find evidence that Stade signed him up for Hollywood. The director, though, did frequent Stade’s Hollywood Bookstore later in the decade and the two seem to have formed some kind of bond, one that allowed Stade to introduce Eisenstein to Mexico’s intellectual community.

The trip also precipitated a break with his family, who disapproved of the woman whom he was then courting. Stade returned in October 1924 and married Anna Marie Knaupp, who was then working for a studio; her family had emigrated from Germany. Marie (or Maria) helped Stade with the bookstore, which had expanded into a book and art store. In 1925, Leonard sold his interest in the store to the two Stades as well as two silent partners. The bookstore did well until the coming the Great Depression, and in 1932 the Stades were forced to sell out to their silent partners. Odo returned to writing. Supposedly, he’d had success sending stories and epigrams to H. L. Mencken in the late 1910s. I can find no evidence to support this connection. (Rubel has him contracting tuberculosis, hiking the Sierras, and marrying in the 1930s.)

I cannot find the Stades in the 1930 census. Starting in 1932, Stade undertook research for a story on Pancho Villa. In September, he and Maria retired to the High Sierras to complete their work. The research formed the basis of the book “Viva Villa,” written by Edgecomb Pinchon, a leftist sympathetic with the Mexican Revolution who wanted to contradict the negative stereotype of Villa in the American media. The book was published in the spring of 1933 . In July of 1933, it was optioned by Metro Goldwyn Meyers; filming began in November.

The production was troubled: directors changed. One of the important actors got drunk and pissed on Mexican soldiers from a balcony as they celebrated the Mexican Revolution. Footage was lost in a plane crash. The filming location changed. Of Fortean interest, the final screenplay was written by the first Fortean, Ben Hecht, who had become a celebrated figure in Hollywood. His adaptation was nominated for an Academy Award. The movie relied on burlesque and never completely rose above Mexican stereotypes, but it also was cynical, blaming the legend of Pancho Villa on a less-than-honest newspaperman. (How Fortean!)

Early in the production, Stade tried to insert himself. (Pinchon had already downplayed Stade’s contribution.) The academic monograph “Open Borders to a Revolution” quotes a letter from Stade to MGM editor Samuel Marx in March 1933 that was three page of corrections. Stade claims that he had not seen proofs for the novel, but did not want to dredge up that unpleasant history with Pinchon again. Instead, he wanted to get the story right, and claimed to be an expert on Mexican affairs. “The idea of the book originated with me,” he he said, and “I had to get all the material, enhanced by my thorough knowledge of Mexico, and things Mexican. I am of course very anxious that the film version follow the facts so far as this will be found possible.” I have not seen the complete letter, but it is striking that, either Stade did not claim to have worked for Pancho Villa or, if he did, that the author of the book chose not to point out this seemingly relevant fact.

Similarly, in a 1938 article for “Trails” magazine, Stade—who gave historical information to the article writer—was noted for having helped write “Viva Villa!," but was not reported to have an official connection to him. Given the contentious history between America, Mexico, and Pancho Villa, there is ample reason for Stade to have downplayed his connection to Villa (albeit, given that “Viva, Villa,” was supposed to resurrect Villa’s reputation, the connection might have been helpful). The point is not that having his connection not mentioned proves he was either with Villa or not, but that making sense of Stade’s biography, given the evidence, is difficult. That he was very interested in Pancho Villa, whatever the nature of that interest, cannot be denied. Nor can his interest in California’s ecology. Both of these would factor in his Fortean career, such as it was.

The 1940 census has the Stades living in Calabasas, where Odo was working on his own account as a writer. (The 1938 “Trails Magazine" article” said he was a “writer of western stories of note.”) I have found a few stories written by him during this period. He published “Journey of the Dead” in “Adventure Novels and Short Stories,” December 1939. (This may have been reprinted in “Short Story Magazine” 3, 1947); “Marihuana Ain’t for Soldados,” in “Adventure Novels and Short Stories,” September 1939, and “Saved by the Enemy,” in the prestigious pulp “The Blue Book,” August 1938. The Stades owned their home, and Odo claimed to have income from other sources as well. Two years later, Stade registered for World War II, giving his address as Topanga and claiming to be self-employed. The online biography has him hoping to join the Navy, but disqualified because of his knee. The draft card mentions as the only distinguishing mark a mole on his left cheek.

According to the on-line biography, Stade took a job with the forest service after he was denied by the Navy. Whether he really wanted to join the navy or not, his joining the Forest Service is one of those unqualified facts in his biography. He served as a dispatcher at the Mt. Baldy district in the San Gabriels, headquartered in Glendora. He stayed with the service until 1959. Likely, it was during this period of life from the early 1940s to the late 1950s, that he came into contact with fellow Forteans and writer E. Hoffman Price and Robert Spencer Carr. Price is the best chronicler of this era.

Price has it that Stade and Carr were “neighbors” while he was living 420 miles away in Redwood City. Probably he was referring to 1942, when Stade was living on Cove Ave., in Los Angeles, and Carr was 10 miles away in Burbank. Exactly how they met is unclear, but they certainly would have had much to discuss—and both were good talkers. Carr, a writing prodigy, had just returned from eight years in Russia, exploring communism where it was practiced and lived. He knew something of the Europe that Stade had abandoned. The two shared a passion for camping in the San Gabriels. for fishing, and for exploring the desert. Carr developed a fondness for desert tortoises, which he urged his friends to raise.

Late in her life, Maria Stade would show an interest in the spiritual world and the work of another Fortean, Max Freedom Long, who studied Hawaiian magic and was an associate of N. Meade Layne and his Borderlands Science Research Association. Long wrote “The Secret Science Behind Miracles” in 1948, and that may suggest that Maria’s interest in Long and his spiritual theories could be dated back to the 1940s. It’s also unclear whether Odo shared this interest.

Odo B. Stade died 5 March 1976.

As a bookseller, Stade had ample opportunity to come across Charles Fort, and there’s every possibility that he read Fort’s books as they came out. But almost certainly he became a Fortean through the devices of Robert Spencer Carr. Carr was mentioned as a a Society member in a 1943 issue of Doubt. Price contributed material in 1945 and 1946. Stade probably joined around this time. There was only one mention of him in Doubt—#18, July 1947. In a letter from a few months later (December), Carr called him a “Fortean extraordinaire.” It’s hard to know from the available material how seriously Stade took Forteanism and what the exact nature of his Fortean philosophy was. But there is no doubt (!!) he would have had at least one good Fortean tale to swap with Carr and Hoffman.

In 1913, Ambrose Bierce the writer traveled to Mexico to investigate the revolution. He was never positively identified again. Bierce was an important literary figure—to Forteans, to writers of weird tales, and indeed to American literature generally, although his influence has largely been overshadowed by his contemporary, Mark Twain. His disappearance, of course, made the news, and caught the eye of Charles Fort, as he was gathering his news clippings of the odd. In Wild Talents, published in 1932, Fort mentioned Bierce’s disappearance, launching it forever into Fortean lore:

“Before I looked into the case of Ambrose Small, I was attracted to it by another seeming coincidence. That there could be any meaning in it seemed so preposterous that, as influenced by much experience, I gave it serious thought. About six years before the disappearance of Ambrose Small, Ambrose Bierce had disappeared. Newspapers all over the world had made much of the mystery of Ambrose Bierce. But what could the disappearance of one Ambrose, in Texas, have to do with the disappearance of another Ambrose in Canada? Was somebody collecting Ambroses? There was in these questions an appearance of childishness that attracted my respectful attention.”

Science fiction author Robert Heinlein incorporated Bierce’s disappearance into one of his favorite stories, “Lost Legacy,” which reworked Fort’s theory of “Wild Talents” and combined it with Theosophical cosmology: Bierce was among a cadre of adepts living on Mt. Shasta, where he was to help the world learn to develop psychic abilities so that humans could transcend their material form and reach a higher spiritual plane. More humorously, Fredric Brown made the collecting of Ambroses a key motif in one of his novels, Compliments of a Fiend. Heinlein’s story was finally published, after much travails, in 1941; Brown’s book appeared in 1950. Fortean Rogers Brackett joked about Ambrose Bierce’s disappearance in The Fortean Society Magazine 10 (Autumn 1944).

Stade, having supposedly ridden with Pancho Villa, had his own tale to tell. It comes to us second hand. In 1929, the young journalist Carey McWilliams published his first book, a biography on Ambrose Bierce. This was at the suggestion of H. L. Mencken. Two years later, he published an article on Bierce’s disappearance for Mencken’s “American Mercury.” By this time, McWilliams had met Stade and had opportunity to report his experiences. (Perhaps this is the point from which came the idea that Stade was sending material to Mencken.) McWilliams wrote,

“There are still further stories. . . . Odo B. Stade, another member of Villa's staff and the author of a history of the revolution, informs me that during the early part of 1914 he knew an elderly American who was attached to the army. This man was about seventy years of age, of medium height, with gray hair. He was very asthmatic. He told his fellow officers that he was an American, and that, if they wanted to give him a name, they might call him Jack Robinson. He scoffed at the tactics of the Mexicans, sneered at their campaigns,and pointed out errors with the eye of an expert. Toward the end of his service he showed a keen interest in hospital trains and the transport of the wounded.

He wore a beard and told Mr. Stade on one occasion that he had been a writer in

the States.

After the engagement at Guadalajara, in November, 1914, "Jack Robinson" quarreled with Villa. Mr. Stade does not know the origin of this quarrel. But a squad under Fierro took Robinson out one evening and shot him, under Villa's orders. A member of this squad, Lieutenant Luis Rojo, told Stade the story the morning after the execution. In company with Rojo, Stade went to the scene, saw the body, and assisted in the burial. Later, after his return to the States, Mr. Stade associated "Jack Robinson" with Bierce, and gave his story to the New York Times in 1920.”

Bierce is disinclined to believe that ‘Jack Robinson’ was Bierce, as are modern commenters, as it would require him to have lived years in Mexico without ever sending word to his daughter. Another reason to be suspicious: if Stade gave his story to the Times in 1920, it never appeared there, not that year, and not afterwards. At the time McWilliams was writing, he was part of a southern California literary scene, and it is likely through this community that he came to meet Stade, then still running his bookstore. Probably, Stade continued to tell the story down the years, into the forties when he met Carr, who would have recognized the Fortean resonances. Certainly knowing the ultimate fate of Bierce could qualify one as a Fortean extraordinaire.

Buried in this Fortean tale is another node in another Fortean nexus, and Stade was connected to that, too, through his only appearance in Doubt. As Heinlein’s story suggested, Mount Shasta was taking on the air of the sacred, reimagined as Tibet in northern California. (There were many such Tibet’s: Henry Miller, another Fortean, thought of Big Sur as California’s answer to Tibet while Carr tried to create a lamasery in the mountains of New Mexico.) Those of a Theosophical bent imagined that Shasta might be the last refuge of the Lemurians who had inhabited the now-vanished continent of Lemur, which had once sat in the Pacific. There was talk of Lemurians living in Shasta, and Ascended Masters who protected ancient wisdom. In the 1930s, Guy Ballard started the “I Am” cult, centering it on Mt. Shasta and the spiritual knwoledge to be learned from Count St. Germain, an immortal said to live there. For many years, there had been reports of little people, Leprechaun like characters scampering about the mountain.

Associated with the Forest Service as he was, Stade was in a position to hear gossip about the goings-on at Shasta. Forteans, many of whom were attracted to the occult and Theosophy, had a curiosity about events there. State’s report on what he heard was apparently sent early in 1947—Thayer teased it in issue 17, having run out of space to print it—before finally appearing in July. The column was titled “Stade Sums Up”:

“We promised to tell what Science found out about Shasta. MFS writes:

‘For some time the Shasta National Forest has been interested in finding out the cause of some stone circles surrounding mounds in the area adjacent to Camp Leaf. Recently, Johnny Noble of the Oakland “Tribune” made a special visit to this area with Lonnie Wilson, “Tribune” photographer; Franklin Fenenga and C. E. Smith, the last two being scientists from the University of California’s Museum of Anthropology.

‘A few weeks previously the Siskiyou County Historical Society made a field trip to the area and Burton J. Westman, one of its members and geologist from Etna, gave a detailed report in which he could find no geological answer to the mounds and rock mosaics, Similarly, the University of California experts could find no anthropological answer.

‘The Oakland “Tribune,” in a feature story on November 22, 1946, hints that since science can’t give the answer, you are entitled to pull your own out of the bag. Maybe the Little People had something to do with it or it might be the Pacific version of Hendrick Hudson.

‘P.S. Local Forest Rangers think that these circles are some of Paul Bunyan’s pancakes that got burned at the edges so the cook threw them out.”

According to that article in the Tribune, the investigation was sparked by an aerial photograph taken by the Forest Service, which showed—in the article’s words—“odd earth formations [that] protrude like swelling grass-covered nipples over 600 acres of the flat prairie near the northwestern foot of the peak. Each concentric mound is the same, 60feet in diameter, with he dirt rising in an almost perfect circle to a crest approximately two feet above the level of the surrounding terrain. Each ring is surrounded by a stone path, or mosaic, the rocks obviously gathered from the millions of volcanic stones tumbled all over the neighborhood.” These mosaics lay in a trench, with the smallest rocks at the bottom, the largest, boulder-sized ones, on top.

Thayer noted that a letter writer to the ‘Tribune’ worked out a volcanic theory, at least to his own satisfaction. And two years later geologist Peter H. Masson would write a scientific article in which he explained the circles as the effect of freezing and thawing on soils with a certain amount of clay content. He surveyed the area, conducted a few experiments, and compared the structure to similar ones from areas that also underwent cycles of freezing and thawing.

Other Forteans were not quite ready to forgo their own pet theories. To Stade’s letter, Thayer appended another from a Fortean I only know as Wakeman, apparently a resident of Oakland, who seems to have been incited to write by the article in his local paper:

“Below are a few notes on the colony of people said to live on Mt. Shasta. Ever since the gold rush the old timer novelists and artists — have centered their attention upon the strange happenings in this region — strange looking persons seen coming out of the tense growth of trees — who would run into hiding when — seen by anyone — oddly dressed — one would sometimes come to the smaller towns for modern commodities — different dress from American Indian —tall, graceful and agile — large head and forehead with a special decoration that came over the center of the forehead to the bridge of the nose —(this to conceal the ‘third eye’) science tells us the nerves are there — --

“Weird lights are seen and when the wind is favorable music is heard — All attempts to locate colony have failed --

“Rosicrucians and other occult groups claim they are the survivors of the Lemurian race who lived on Lemur now sunken in the Pacific.

Some years ago the newspapers sent investigators with the usual results. As one reporter stated: The people did not want to make statements for the press which would make them appear simple and gullible.”

Thayer liked best a more politically edged theory, offered by Ad Schuster, a columnist for the Tribune: He suggested that the circles mark the site where whites “started giving the Indians the run-around.” Thayer himself had just taken up the cause of Native Americans, especially the work of Iktomi, and so this comment fit with his own political agenda.

Stade’s own response suggests a Fortean sense of whimsy, even as he seemed reluctant to give up on the explanatory power of science. He seems derisive of the idea that without science one should just pick any old explanation. And the two he offers are clearly in jest, coming from outlandish and obviously fictional American folklore. The reference to Paul Bunyan is obvious, and needs no explanation. The Hendrick Hudson call-out, though, is a bit more obscure. Presumably he was referring to the story Rip Van Winkle, at the beginning of which Rip discovers (what he later learn to be) the ghost of explorer Henry Hudson and his crewmates working busily on a mountain. State could have pointed to the Lemurians—implausible, but still taken seriously by many—but chose instead a reference that was obviously fictional. That says something about his Forteanism. Maybe it is fair to call it extraordinary, capturing the jocularity of Fort and suspending judgment.

At the time, Mexico was in the midst of a revolution, whose rough chronological contours are 1910 and 1920. As most revolutions, it was a complicated affair, with many partitions. Among the revolutionary generals was Pancho Villa, who seized haciendas and gave the land to the poor. His supporters, at least in the second half of the revolution, included German officials. The biography of Stade claims that he, too, was a Villa supporter, negotiating Austro-Hungary’s exportation of gold in return for arms, which Stade helped to obtain from the United States. Stade was supposedly hurt twice, including having his knee shattered by bullets, before leaving Mexico suffering from malaria. There is a picture of Pancho Villa, with Stade to his right, but the provenance and attribution of names is uncertain.

There are several other accounts of this period in Stade’s life. Much later, living in southern California, Stade would become a father-figure to Michael Clark Rubel [NB: Edited September 2015 to correct spelling from Ruble to Rubel, et passim.]. Rubel would, even later, remember the stories that Stade told him: about how he switched boots with Villa, because Stade’s were better. And Stade bought a better pistol from Villa’s girlfriend to give to the revolutionary. And how these artifacts came into Rubel’s possession when he was just 15. According to Rubel, Stade was with Villa in 1923 when Villa was assassinated. Only Odo and another man survived the strafing by a Tommy Gun, Odo showing horrible scars on his chest much later, maybe only three, maybe only from ricochets, but bad enough to make Rubel wonder how Stade survived.

There is also a documentary record. According to U.S. Immigration papers, the 1920 census, and Stade’s 1924 application for a U.S. Passport, he reached the U.S. in August 1913 via New York. A clerk, five-foot-eight and 135 pounds, he renounced his allegiance to William II, the German Emperor on 6 January 1914. He’s in the Los Angeles City directories starting in 1914. It’s always possible that he dissembled in these records. Villa was no friend of America, having attacked Columbus, Mew Mexico in 1916. All but three of Stade’s documents post-date Villa’s split with America. The most relevant, though, does date from before this break and denies any connection to Mexico. Stade reports he traveled to New York City from Bremen, in northwest Germany.

Another problem with the timeline given by Stade’s associates is that Villa did not receive German (or Austro-Hungarian) aid before 1915, by which time Stade was living in Los Angeles and working as a manager. As well, the description of him given in his immigration papers is very different than the one offered in the biography: “His doctor recommended living in the wild, so in May of 1916 Odo hiked to Tahoe and on to the High Sierras where he lived off the land for six months. He had weighed only 108 pounds when he left for the mountains, and when he came back, he weighted 174.” For what it is worth, Stade is in the 1916 and 1917 Los Angeles City Directories, his occupation given as a clerk. (Another friend of Stade’s claimed he was working for the French government—but there is nothing in Stade’s biography to suggest he was suggest French politically, as opposed to linguistically.)

Further calling into question how much of his early life was invented, the biography credits Stade with establishing the altitude of some of the Sierra peaks during his time in the wilderness. The problem here is that the California Geological Survey had been established before Stade was even born, in 1863, and there had been extensive exploration since then. A detailed map of the Sierras was published by the U.S. Geological Service in 1912—when Stade was supposedly taking over in Mexico. I find no reference to Stade in California Geological Survey publications.

But then there’s the research of others. Historian Lawrence D. Taylor has examined the role of mercenaries in the Mexican Revolution. His 1986 paper for “The Americas” did not mention Stade. His 1993 monograph does; but it is in Spanish, published in Mexico, and difficult to come by. Supposedly, there is documentary evidence proving Stade was among the Villanistas. If, indeed, Stade aided Pancho Villa, there are multiple accounts of why he did so, and how he came to Mexico.

In addition to the online biography stating that he was an official for the (moribund) Austro-Hungary empire, there are two other stories. One, which was reported in 1959 newspapers, had him as associated with a mining company, the French concern “International Company of Mines.” That would explain his interest in exporting gold, and, indeed, these accounts focus on his mineralogical successes. He left Mexico, in this narrative, in 1915, tired from fighting and suffering from malaria. The other explanation is from Taylor, and grants Stade an official capacity. Stylized Ode B. Stade, he was referred to as consejero militar, or military counselor. At least, that was an official position with Villa, if not with other governments. Perhaps, as some have said, he was simply a mercenary, finding himself in Mexico after some time in the Austrian navy—the exact time itself of some debate. It may be that, on this account, his Mexico adventures occurred in 1910 and 1911.

The on-line biography has him meeting Adam Clark Vroman, a bookseller and photographer, shortly after arriving in California, and that seems to be true, whether he came straight from Europe or via Mexico. The 1914 Los Angeles city directory has him as a salesman for Vroman; in 1916, he was managing a different bookstore, Hollywood Bookstore. That seems to have been a short time position, though, as in 1917 he was a clerk and his registration for the draft put him as a laborer for D. W. Colby of Colby Springs—likely this means he was working in a part of the San Gabriel Mountains that became the Angeles National Forest in 1908. Here, at least, he was in the mountains.

One 1959 newspaper article—in the Pasadena “Independent Star-News”—reported he spent the years 1915 to 1918 exploring the San Gabriel mountains. Part of the reason was health. He worked for Colby. He ran mules through the mountains supplying camps. He watched the number of hikers explode. He watched the number of big horn sheep decline. He fought wildfires. He was just shy of forty years old. All of this detail, though, is retrospective, nothing from the time, and one feels that Stade was a great storyteller, perhaps given to exaggeration.

A few other bits of information from the draft registration bear notice. Stade was supporting his mother. (His father had died.) He reports that he served in the German Navy for fourteen months—no connection to the French government—where he achieved the rank of corporal—so less than the five years reported in the biography, and not a lieutenant. The registration also noted that he had no disabilities, which certainly raises questions about his knee being shot up while he was with Pancho Villa in Mexico. Or his chest. The government would have every reason to get the answer to this question correct. The draft card was signed 5 June 1917.

By 1920, he was back to managing a bookstore. Still single, Stade was a boarder with the Rentch family. Originally from West Virginia, the patriarch, Louis, was descended from a family out of Alsace-Lorraine, too. Although Stade was said to be able to read and write English, he gave his birth language as French (while his parents, he said, both spoke German). He was also supposedly attending school. Likely he was back with the Hollywood Bookstore, but his relationship with that institution is a vexed one. In 1929, he would tell the magazine “Motion Picture” that he had established it fifteen years before—which doesn’t quite fit with his employment history, albeit he had a frequent association with the place. According to the biography, he took over the managership of Hollywood Bookstore—it was owned by Frederick G. Leonard—in 1916, after his Sierra wanderings, at the urging of Vroman. Vroman died in July of 1916, which makes this story just possible.

Supposedly, Stade became associated with Hollywood in its infancy. That 1959 article had him playing bit parts in “The Miracle Man,” “Right to Happiness,” “Blind Husbands,” and “The World and Its Women.” (The Internet Movie Database does not list him among the cast members for any of these films.) This Hollywood link, supposedly, led him to Dick Grace’s “Squadron of Death,” a stunt-flying group. I can find no link between him and these flyers, beyond the much-later reports, and there is no mention of how injuries that he may have suffered with Pancho Villa affected this career.

On 28 April 1924, Stade applied for a passport. Further complicating his story of arms-dealing with Pancho Villa, he declared not only that he had arrived from Bremen in August 1913 but that he had resided in the United States for ten continuous years. His naturalization process had been completed 7 May 1920. He listed his occupation as bookstore manager—identification was provided for him by Frederick G. Leonard, who gave his occupation as banking. The two had known each other for ten years, Leonard attested, suggesting that he did own the bookstore, but Stade managed it. He reported he would travel to Britain, Germany, and Austria on business, and Czechoslavakia, France, and Hungary on pleasure. It is worth noting that the passport listed no distinguishing marks, such as a bad knee or scarred chest. He was mustachioed.

According to the on-line biography, Stade undertook the travel at the bequest of a Hollywood studio, which wanted him to conduct research for them. The 1959 newspaper report had him as a talent scout, and a perspicacious one at that. “One of the big names that Stade signed to contract on that trip was Sergei Eisenstein, Russian director of such great films as “Potemkin” and “Ten Days that Shook the World.” Eisenstein will recur in another Fortean entry, and would be connected to Mexico, but I cannot find evidence that Stade signed him up for Hollywood. The director, though, did frequent Stade’s Hollywood Bookstore later in the decade and the two seem to have formed some kind of bond, one that allowed Stade to introduce Eisenstein to Mexico’s intellectual community.

The trip also precipitated a break with his family, who disapproved of the woman whom he was then courting. Stade returned in October 1924 and married Anna Marie Knaupp, who was then working for a studio; her family had emigrated from Germany. Marie (or Maria) helped Stade with the bookstore, which had expanded into a book and art store. In 1925, Leonard sold his interest in the store to the two Stades as well as two silent partners. The bookstore did well until the coming the Great Depression, and in 1932 the Stades were forced to sell out to their silent partners. Odo returned to writing. Supposedly, he’d had success sending stories and epigrams to H. L. Mencken in the late 1910s. I can find no evidence to support this connection. (Rubel has him contracting tuberculosis, hiking the Sierras, and marrying in the 1930s.)

I cannot find the Stades in the 1930 census. Starting in 1932, Stade undertook research for a story on Pancho Villa. In September, he and Maria retired to the High Sierras to complete their work. The research formed the basis of the book “Viva Villa,” written by Edgecomb Pinchon, a leftist sympathetic with the Mexican Revolution who wanted to contradict the negative stereotype of Villa in the American media. The book was published in the spring of 1933 . In July of 1933, it was optioned by Metro Goldwyn Meyers; filming began in November.

The production was troubled: directors changed. One of the important actors got drunk and pissed on Mexican soldiers from a balcony as they celebrated the Mexican Revolution. Footage was lost in a plane crash. The filming location changed. Of Fortean interest, the final screenplay was written by the first Fortean, Ben Hecht, who had become a celebrated figure in Hollywood. His adaptation was nominated for an Academy Award. The movie relied on burlesque and never completely rose above Mexican stereotypes, but it also was cynical, blaming the legend of Pancho Villa on a less-than-honest newspaperman. (How Fortean!)

Early in the production, Stade tried to insert himself. (Pinchon had already downplayed Stade’s contribution.) The academic monograph “Open Borders to a Revolution” quotes a letter from Stade to MGM editor Samuel Marx in March 1933 that was three page of corrections. Stade claims that he had not seen proofs for the novel, but did not want to dredge up that unpleasant history with Pinchon again. Instead, he wanted to get the story right, and claimed to be an expert on Mexican affairs. “The idea of the book originated with me,” he he said, and “I had to get all the material, enhanced by my thorough knowledge of Mexico, and things Mexican. I am of course very anxious that the film version follow the facts so far as this will be found possible.” I have not seen the complete letter, but it is striking that, either Stade did not claim to have worked for Pancho Villa or, if he did, that the author of the book chose not to point out this seemingly relevant fact.

Similarly, in a 1938 article for “Trails” magazine, Stade—who gave historical information to the article writer—was noted for having helped write “Viva Villa!," but was not reported to have an official connection to him. Given the contentious history between America, Mexico, and Pancho Villa, there is ample reason for Stade to have downplayed his connection to Villa (albeit, given that “Viva, Villa,” was supposed to resurrect Villa’s reputation, the connection might have been helpful). The point is not that having his connection not mentioned proves he was either with Villa or not, but that making sense of Stade’s biography, given the evidence, is difficult. That he was very interested in Pancho Villa, whatever the nature of that interest, cannot be denied. Nor can his interest in California’s ecology. Both of these would factor in his Fortean career, such as it was.

The 1940 census has the Stades living in Calabasas, where Odo was working on his own account as a writer. (The 1938 “Trails Magazine" article” said he was a “writer of western stories of note.”) I have found a few stories written by him during this period. He published “Journey of the Dead” in “Adventure Novels and Short Stories,” December 1939. (This may have been reprinted in “Short Story Magazine” 3, 1947); “Marihuana Ain’t for Soldados,” in “Adventure Novels and Short Stories,” September 1939, and “Saved by the Enemy,” in the prestigious pulp “The Blue Book,” August 1938. The Stades owned their home, and Odo claimed to have income from other sources as well. Two years later, Stade registered for World War II, giving his address as Topanga and claiming to be self-employed. The online biography has him hoping to join the Navy, but disqualified because of his knee. The draft card mentions as the only distinguishing mark a mole on his left cheek.

According to the on-line biography, Stade took a job with the forest service after he was denied by the Navy. Whether he really wanted to join the navy or not, his joining the Forest Service is one of those unqualified facts in his biography. He served as a dispatcher at the Mt. Baldy district in the San Gabriels, headquartered in Glendora. He stayed with the service until 1959. Likely, it was during this period of life from the early 1940s to the late 1950s, that he came into contact with fellow Forteans and writer E. Hoffman Price and Robert Spencer Carr. Price is the best chronicler of this era.

Price has it that Stade and Carr were “neighbors” while he was living 420 miles away in Redwood City. Probably he was referring to 1942, when Stade was living on Cove Ave., in Los Angeles, and Carr was 10 miles away in Burbank. Exactly how they met is unclear, but they certainly would have had much to discuss—and both were good talkers. Carr, a writing prodigy, had just returned from eight years in Russia, exploring communism where it was practiced and lived. He knew something of the Europe that Stade had abandoned. The two shared a passion for camping in the San Gabriels. for fishing, and for exploring the desert. Carr developed a fondness for desert tortoises, which he urged his friends to raise.

Late in her life, Maria Stade would show an interest in the spiritual world and the work of another Fortean, Max Freedom Long, who studied Hawaiian magic and was an associate of N. Meade Layne and his Borderlands Science Research Association. Long wrote “The Secret Science Behind Miracles” in 1948, and that may suggest that Maria’s interest in Long and his spiritual theories could be dated back to the 1940s. It’s also unclear whether Odo shared this interest.

Odo B. Stade died 5 March 1976.

As a bookseller, Stade had ample opportunity to come across Charles Fort, and there’s every possibility that he read Fort’s books as they came out. But almost certainly he became a Fortean through the devices of Robert Spencer Carr. Carr was mentioned as a a Society member in a 1943 issue of Doubt. Price contributed material in 1945 and 1946. Stade probably joined around this time. There was only one mention of him in Doubt—#18, July 1947. In a letter from a few months later (December), Carr called him a “Fortean extraordinaire.” It’s hard to know from the available material how seriously Stade took Forteanism and what the exact nature of his Fortean philosophy was. But there is no doubt (!!) he would have had at least one good Fortean tale to swap with Carr and Hoffman.

In 1913, Ambrose Bierce the writer traveled to Mexico to investigate the revolution. He was never positively identified again. Bierce was an important literary figure—to Forteans, to writers of weird tales, and indeed to American literature generally, although his influence has largely been overshadowed by his contemporary, Mark Twain. His disappearance, of course, made the news, and caught the eye of Charles Fort, as he was gathering his news clippings of the odd. In Wild Talents, published in 1932, Fort mentioned Bierce’s disappearance, launching it forever into Fortean lore:

“Before I looked into the case of Ambrose Small, I was attracted to it by another seeming coincidence. That there could be any meaning in it seemed so preposterous that, as influenced by much experience, I gave it serious thought. About six years before the disappearance of Ambrose Small, Ambrose Bierce had disappeared. Newspapers all over the world had made much of the mystery of Ambrose Bierce. But what could the disappearance of one Ambrose, in Texas, have to do with the disappearance of another Ambrose in Canada? Was somebody collecting Ambroses? There was in these questions an appearance of childishness that attracted my respectful attention.”

Science fiction author Robert Heinlein incorporated Bierce’s disappearance into one of his favorite stories, “Lost Legacy,” which reworked Fort’s theory of “Wild Talents” and combined it with Theosophical cosmology: Bierce was among a cadre of adepts living on Mt. Shasta, where he was to help the world learn to develop psychic abilities so that humans could transcend their material form and reach a higher spiritual plane. More humorously, Fredric Brown made the collecting of Ambroses a key motif in one of his novels, Compliments of a Fiend. Heinlein’s story was finally published, after much travails, in 1941; Brown’s book appeared in 1950. Fortean Rogers Brackett joked about Ambrose Bierce’s disappearance in The Fortean Society Magazine 10 (Autumn 1944).

Stade, having supposedly ridden with Pancho Villa, had his own tale to tell. It comes to us second hand. In 1929, the young journalist Carey McWilliams published his first book, a biography on Ambrose Bierce. This was at the suggestion of H. L. Mencken. Two years later, he published an article on Bierce’s disappearance for Mencken’s “American Mercury.” By this time, McWilliams had met Stade and had opportunity to report his experiences. (Perhaps this is the point from which came the idea that Stade was sending material to Mencken.) McWilliams wrote,

“There are still further stories. . . . Odo B. Stade, another member of Villa's staff and the author of a history of the revolution, informs me that during the early part of 1914 he knew an elderly American who was attached to the army. This man was about seventy years of age, of medium height, with gray hair. He was very asthmatic. He told his fellow officers that he was an American, and that, if they wanted to give him a name, they might call him Jack Robinson. He scoffed at the tactics of the Mexicans, sneered at their campaigns,and pointed out errors with the eye of an expert. Toward the end of his service he showed a keen interest in hospital trains and the transport of the wounded.

He wore a beard and told Mr. Stade on one occasion that he had been a writer in

the States.

After the engagement at Guadalajara, in November, 1914, "Jack Robinson" quarreled with Villa. Mr. Stade does not know the origin of this quarrel. But a squad under Fierro took Robinson out one evening and shot him, under Villa's orders. A member of this squad, Lieutenant Luis Rojo, told Stade the story the morning after the execution. In company with Rojo, Stade went to the scene, saw the body, and assisted in the burial. Later, after his return to the States, Mr. Stade associated "Jack Robinson" with Bierce, and gave his story to the New York Times in 1920.”

Bierce is disinclined to believe that ‘Jack Robinson’ was Bierce, as are modern commenters, as it would require him to have lived years in Mexico without ever sending word to his daughter. Another reason to be suspicious: if Stade gave his story to the Times in 1920, it never appeared there, not that year, and not afterwards. At the time McWilliams was writing, he was part of a southern California literary scene, and it is likely through this community that he came to meet Stade, then still running his bookstore. Probably, Stade continued to tell the story down the years, into the forties when he met Carr, who would have recognized the Fortean resonances. Certainly knowing the ultimate fate of Bierce could qualify one as a Fortean extraordinaire.

Buried in this Fortean tale is another node in another Fortean nexus, and Stade was connected to that, too, through his only appearance in Doubt. As Heinlein’s story suggested, Mount Shasta was taking on the air of the sacred, reimagined as Tibet in northern California. (There were many such Tibet’s: Henry Miller, another Fortean, thought of Big Sur as California’s answer to Tibet while Carr tried to create a lamasery in the mountains of New Mexico.) Those of a Theosophical bent imagined that Shasta might be the last refuge of the Lemurians who had inhabited the now-vanished continent of Lemur, which had once sat in the Pacific. There was talk of Lemurians living in Shasta, and Ascended Masters who protected ancient wisdom. In the 1930s, Guy Ballard started the “I Am” cult, centering it on Mt. Shasta and the spiritual knwoledge to be learned from Count St. Germain, an immortal said to live there. For many years, there had been reports of little people, Leprechaun like characters scampering about the mountain.

Associated with the Forest Service as he was, Stade was in a position to hear gossip about the goings-on at Shasta. Forteans, many of whom were attracted to the occult and Theosophy, had a curiosity about events there. State’s report on what he heard was apparently sent early in 1947—Thayer teased it in issue 17, having run out of space to print it—before finally appearing in July. The column was titled “Stade Sums Up”:

“We promised to tell what Science found out about Shasta. MFS writes:

‘For some time the Shasta National Forest has been interested in finding out the cause of some stone circles surrounding mounds in the area adjacent to Camp Leaf. Recently, Johnny Noble of the Oakland “Tribune” made a special visit to this area with Lonnie Wilson, “Tribune” photographer; Franklin Fenenga and C. E. Smith, the last two being scientists from the University of California’s Museum of Anthropology.

‘A few weeks previously the Siskiyou County Historical Society made a field trip to the area and Burton J. Westman, one of its members and geologist from Etna, gave a detailed report in which he could find no geological answer to the mounds and rock mosaics, Similarly, the University of California experts could find no anthropological answer.

‘The Oakland “Tribune,” in a feature story on November 22, 1946, hints that since science can’t give the answer, you are entitled to pull your own out of the bag. Maybe the Little People had something to do with it or it might be the Pacific version of Hendrick Hudson.

‘P.S. Local Forest Rangers think that these circles are some of Paul Bunyan’s pancakes that got burned at the edges so the cook threw them out.”

According to that article in the Tribune, the investigation was sparked by an aerial photograph taken by the Forest Service, which showed—in the article’s words—“odd earth formations [that] protrude like swelling grass-covered nipples over 600 acres of the flat prairie near the northwestern foot of the peak. Each concentric mound is the same, 60feet in diameter, with he dirt rising in an almost perfect circle to a crest approximately two feet above the level of the surrounding terrain. Each ring is surrounded by a stone path, or mosaic, the rocks obviously gathered from the millions of volcanic stones tumbled all over the neighborhood.” These mosaics lay in a trench, with the smallest rocks at the bottom, the largest, boulder-sized ones, on top.

Thayer noted that a letter writer to the ‘Tribune’ worked out a volcanic theory, at least to his own satisfaction. And two years later geologist Peter H. Masson would write a scientific article in which he explained the circles as the effect of freezing and thawing on soils with a certain amount of clay content. He surveyed the area, conducted a few experiments, and compared the structure to similar ones from areas that also underwent cycles of freezing and thawing.

Other Forteans were not quite ready to forgo their own pet theories. To Stade’s letter, Thayer appended another from a Fortean I only know as Wakeman, apparently a resident of Oakland, who seems to have been incited to write by the article in his local paper:

“Below are a few notes on the colony of people said to live on Mt. Shasta. Ever since the gold rush the old timer novelists and artists — have centered their attention upon the strange happenings in this region — strange looking persons seen coming out of the tense growth of trees — who would run into hiding when — seen by anyone — oddly dressed — one would sometimes come to the smaller towns for modern commodities — different dress from American Indian —tall, graceful and agile — large head and forehead with a special decoration that came over the center of the forehead to the bridge of the nose —(this to conceal the ‘third eye’) science tells us the nerves are there — --

“Weird lights are seen and when the wind is favorable music is heard — All attempts to locate colony have failed --

“Rosicrucians and other occult groups claim they are the survivors of the Lemurian race who lived on Lemur now sunken in the Pacific.

Some years ago the newspapers sent investigators with the usual results. As one reporter stated: The people did not want to make statements for the press which would make them appear simple and gullible.”

Thayer liked best a more politically edged theory, offered by Ad Schuster, a columnist for the Tribune: He suggested that the circles mark the site where whites “started giving the Indians the run-around.” Thayer himself had just taken up the cause of Native Americans, especially the work of Iktomi, and so this comment fit with his own political agenda.

Stade’s own response suggests a Fortean sense of whimsy, even as he seemed reluctant to give up on the explanatory power of science. He seems derisive of the idea that without science one should just pick any old explanation. And the two he offers are clearly in jest, coming from outlandish and obviously fictional American folklore. The reference to Paul Bunyan is obvious, and needs no explanation. The Hendrick Hudson call-out, though, is a bit more obscure. Presumably he was referring to the story Rip Van Winkle, at the beginning of which Rip discovers (what he later learn to be) the ghost of explorer Henry Hudson and his crewmates working busily on a mountain. State could have pointed to the Lemurians—implausible, but still taken seriously by many—but chose instead a reference that was obviously fictional. That says something about his Forteanism. Maybe it is fair to call it extraordinary, capturing the jocularity of Fort and suspending judgment.