Stretching the bounds of Forteanism—setting the stage for Dianetics—while obscuring much else.

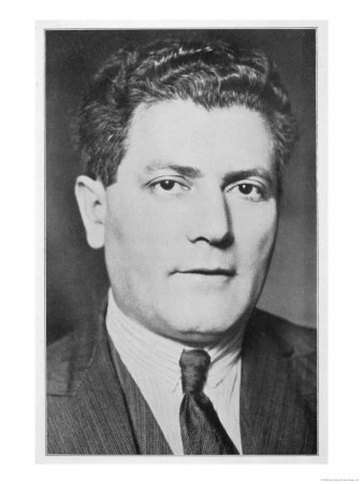

Nandor Fodor was a Hungarian Fortean, ghost hunter, spiritualist, psychic investigator, and professional psychoanalyst. Also a journalist, author, and political agitator.

Fodor was born 13 May 1895 in Beregszasz, Hungary, one of eighteen children. I believe the family was Jewish, the father’s name Aron Friedlander and the mother’s Zali Goldstein; I don’t know why the surname was changed to Fodor. Two children were born after Nandor, but both died very young; seven other older siblings also died while children. The youngest surviving, Nandor was, by his own account, his father’s favorite. He got a law degree in 1917 and practiced law until 1921, missing out on World War I. If I am right about his heritage, his older brother was Lajos Fodor, also a lawyer.

Nandor Fodor was a Hungarian Fortean, ghost hunter, spiritualist, psychic investigator, and professional psychoanalyst. Also a journalist, author, and political agitator.

Fodor was born 13 May 1895 in Beregszasz, Hungary, one of eighteen children. I believe the family was Jewish, the father’s name Aron Friedlander and the mother’s Zali Goldstein; I don’t know why the surname was changed to Fodor. Two children were born after Nandor, but both died very young; seven other older siblings also died while children. The youngest surviving, Nandor was, by his own account, his father’s favorite. He got a law degree in 1917 and practiced law until 1921, missing out on World War I. If I am right about his heritage, his older brother was Lajos Fodor, also a lawyer.

Nandor had an active imagination, and fell in love with fantastic literature. Years later, he would remember, “When I was young, science fiction was H.G. Wells. I was enraptured by The Time Machine, The War of the Worlds, The Wonderful Visit, Dr. Moreaus’s Island, When the Sleeper Awakes, Men Like Gods, In the Year of the Comet, etc. I must have lived in his world even before. I vaguely recall a time when I pretended to write a book. I never got beyond the title (which I now do not remember) and under it I wrote, by H.G. Wells. I did not choose his name as a pseudonym. I thought that a write can choose as his own any name he likes. I suppose this was my earliest identification with science fiction. As that literature was still in the limbo of my youth, I had to find food for my vivid imagination in related fields. In my university years, I had found it in Rider Haggard’s African mysteries. I learned English mainly through him. I read every book the Tauchnitz paperback edition from Germany brought within my range, sometimes a volume a day, being glued to it from morning till night. He-Who-Sleeps-Awake (Macumazan in native for Allan Quartermaine) was my great adventurer. My romantic admiration for his wisdom and heroic doings was coupled with the fascination for the witch doctors he constantly encountered. There I learned, for the first time, of telepathy, clairvoyance and other mysterious psychic and magical faculties. They left a lasting impression on my mind. In late years, I have tried repeatedly to recapture the spell of Allen Quartermain’s [sic] and the witch doctors’ adventures by going back to the books that once had enthralled me. But the ecstasy was gone, the flavor was stale and I was no longer carried away.”

Breaking his father’s heart—the older man rightly predicted he would never again see his youngest son—Nandor migrated to the United States in 1921, where he was a journalist at the Hungarian-language American Hungarian People’s Voice. He would work as a journalist for more than a decade, but still valued his legal skills for letting him evaluate evidence: this is a common theme among investigators of the strange, trusting their bullshit detectors because of their training, particularly in journalism and law (since they are rarely trained in the sciences, and these are other professions concerned with the establishment of truths). While doing his work, he came across a book on parapsychology which recaptured the passion that Haggard and other writers of fantasy could no longer:

“If admiration is a kind of identification, I had identified myself with Macumazan of my youth.I am conscious, however, that I never wanted to become an explorer of unknown regions of the globe. Another outlet was presented to my devouring interest when I discovered the explorers of the unknown continents of the mind . . . I was seized by a burning curiosity and practically engraved on my mind every page, photograph and footnote. Here was something more promising than the darkest Africa, with adventures far more entrancing and of immense personal significance.”

The exact book he discovered is unclear. In his own account, Fodor has it as Cesar Lombroso’s After Death—What?, which had been published in 1909, at the end of the pioneering criminologist’s long life. Fodor’s follower (and fellow Fortean) Leslie Shepherd pegged the book as Hereford Carrington’s 1919 Modern Psychic Phenomena. Maybe it was at the Public Library on 42nd Street, maybe a Fourth Avenue bookstore. In either case, it wasn’t Fort—although he may have come across Fort’s first, The Book of the Damned, which was published in 1919 (with a street date of 1920) as he became addicted to the topic, eating only coffee and a cinnamon bun for lunch (rather than at the many surrounding Hungarian restaurants) to save money for books.

Fodor married in 1922, another Hungarian, Amaira Iren (Irene); a few years his junior, she had been in the States since 1912. But his obsession continued— “I remember—to my shame as a young husband—reading int late into the night after she had gone to bed,” he wrote in 1959. The two must have connected some time, though, since Irene gave birth to Andres in April 1923. In the course of his research, he met Carrington himself, who introduced Fodor to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Shepherd believes that Fodor took Carrington as a model. In 1926, Fodor met another man who would have a profound effect on his life, the Hungarian ex-patriot and psychoanalyst Sandor Ferenczi. By this time, his father had passed, and Fodor seemed intent to make America his home, applying for naturalization.

Fodor became a spiritualist. He saw that there was a lot of interest in the subject—Scientific American was offering cash money for definitive proof—and he was able to see stories on spiritualism to English language outlets. He attended seances, and at one of them heard from his dead father. He was young and naive at the time, by his own admission, and credulous, but that moment would remain with him as one of three times in his entire four-decade career that he had undeniable proof of life after death: and that was enough to commit him to spiritualism. He didn’t buy all spiritualist thought, though, and that was the seed of an eventual split.

For reasons unclear, the Fodor family relocated to England in 1928; probably it had to do with work. Around this time he interviewed the newspaper magnate Lord Rothermere (Harold Harmsworth). Lord Rothermere had little interest in Spiritualism, but was intent on making his papers widely popular, and Fodor had gained a reputation for punchy prose—at least by his own account—which may have owed something to his learning the language from writers of fantasy. There was also a political connection. Rothermere wanted to lighten the burden of World War I treaties on Hungary, a cause that was also close to the heart of Fodor. (According to Wikipedia, Rothermere was motivated less by beneficence and more by a mistress and hope that he might become a royal there.) Fodor became Rothermere’s secretary, in charge of Hungarian affairs. If I am correct about Fodor’s heritage, then his brother was also involved in politics around this time, legal consultant for a Zionist movement.

There was an active Spiritualist movement in London, and Fodor soon attached himself to it. Fodor was taken by H.G. Wells The Science of Life when it appeared in 1931—the same year as Fort’s Lo!—and reviewed the skeptical chapter on life after death for Life, the weekly magazine of the London Spiritualist Alliance, concluding, “Whether for serious study or to draw ideas of association for his brilliantly fertile mind, he would be welcome among psychic investigators. Let him come to scoff. He may remain to pray.” (Wells was an interest of other Forteans, too: Dreiser tried to convert him to the Society; Alexander Woollcott was amazed by The Science of Life, and Kenneth Rexroth considered Wells’s Research Magnificent one of his lodestars.) Trying to make sense of all that he was reading, Fodor had been indexing the material and in the early 1930s put out—with a London publisher—The Encyclopedia of Psychic Science. Around the same time, he was appointed assistant editor of Light. Half-a-century old now, the magazine had become stodgy and with another newspaperman he was brought on board to give it new life. In 1936, he became the London correspondent for the Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research.

He also became a research officer with the International Institute for Psychical Research, and had some unsatisfying psychic experiences. He tried to contact Lord Rothermere’s dead brother, Lord Northcliffe, which lead to nothing. He also spent months waiting for a spirit to guide him in automatic writing. His wife—an artist and, he reckoned, generally more sensitive—felt the impulse but produced nothing of note. The spirit never moved him though. The “chasing a will-o’-the-wisp, perhaps my most fascinating adventure, the best illustration of the utterly stupid and imbecilic length to which a believer allows himself to be carried.” He investigated Gef The Talking Mongoose (yes, mongoose), which supposedly haunted a farm on the Isle of Man (later a center of English witchcraft) and came away convinced that it was, of anything, a hoax—although one that fit with his developing theories about psychic phenomena.

The 1930s saw Fodor making two connections that allowed him to overcome his naiveté. The first was meeting another future Fortean, the medium Eileen Garrett, who was being studied by a number of spiritualist researchers, among them Hereward Carrington. Garrett was, by the account of all the spiritualists she knew, a gifted trance medium. But she herself doubted whether the so-called controls who spoke through her were really spirits—indeed, she spent her whole life wrestling with this question. Fodor was impressed by this line of thinking. He wondered, as Garrett did herself, if these controls, these spirits, were some form of subconscious manifestation, a secondary personality, perhaps. He noted that her main control, Uvani, never claimed to speak to Fodor’s father during their seances, but reported information Garrett may have picked up from his mind—perhaps, then, it was ESP or telepathy (just like in the Alan Quartermain books!) and not contact with the other side at all.

These musings took more coherent form after the second connection, with Elizabeth Severn, a student of Ferenczi, and so a psychoanalyst only once removed from Freud himself. Fodor began studying psychoanalysis rigorously. He came to think that, perhaps, many mediums were in contact with the collective unconscious, that the voices they heard were archetypes: the Eastern Masters, for example, just versions of the wise man. Garrett influenced him here, too. She was known to “lay ghosts”—to calm hauntings and poltergeists—by diagnosing the psychological disturbances in the family, and he did similarly. He told a story of helping a homicidal man not by dismissing the voices he heard but by subtly altering them, such that they became positive, the man helpful. The last Fodor heard of him, he was a dog whisperer, helping befuddled owners understand their canines.

The turn to psychoanalysis was one way around the Spiritualist’s constant conundrum: that every phenomena was either a hoax or proof of life after death. For Fodor, even hoaxes became worthy of study, because they opened a window into the psychology of the (fake) medium. That psychoanalysis, with its focus on sex, was the key to understanding this psychology was proved beyond a shadow of a doubt to him when one of the frauds he unveiled was shown to secret the objects she claims dot psychically materialize in her vagina. Girls near menarche became a special focus of his research: relying on the gender stereotypes of the day, they were seen as especially volatile and likely to cause poltergeist activities, often subconsciously. Fort had made similar points in Wild Talents and the Forteans would take up the idea ironically with their interest in “Wonets.”

Other spiritualists were not so pleased with Fodor’s turn toward psychoanalysis—nor were all of Freud’s disciples pleased with the connection. The history here, though, is more complicated than Fodor had it. Psychoanalysis had long been intertwined with studies of the paranormal in Britain—it came to the public’s attention first through the writings of Frederic Myers, founder of the Society for Psychical Research. Since that time, though, some Freudians had tried to disentangle the two, worried that association with psychical research would make their science seem fringe, while some psychical researchers turned to psychoanalysis exactly because it seemed to give their own studies a scientific cachet. At the same time, there were psychoanalysts who continued to probe the psychical without worrying over reputation. A tension, then, within the two, overlapping fields, as workers from both sides tried to connect them, and others sever the connections.

Fodor felt particularly exposed, and seemed to draw the ire of many psychical researchers. In the mid-1930s, he had committed to living in the London area—his American naturalization file contains a letter from him acknowledging he had left the U.S. less than five years after he was naturalized and did not plan on returning, making that naturalization null and void. Yet the English spiritualists publicly attacked him for his turn to psychoanalysis and bringing in the subject of sex. There was much public back and forth, and even a lawsuit. In 1938, Irene brought one of Fodor’s manuscripts connecting psychical research and psychoanalysis to Freud, who was then living in London, exiled by the rise of Nazism. Fodor was much buoyed when he received a letter of support from Freud praising his research.

However supported he might have finally felt with Freud’s acknowledgment, Fodor wasn't long for Britain. He returned to America in spring 1939—I’m not sure why—and another Fortean connection. While they settled, Nandor and Irene stayed with Ben Hecht’s first wife, Marie Armstrong Essipoff. Apparently she had (or had developed) an interest in the outré. During the 1950s she would claim to see a UFO, for example. And at the time, she and Fodor tried table turning, though without success. Eventually, Fodor opened a psychoanalytic practice and settled down making his living that way. He also continued his investigations and writing on parapsychology.

His views on the importance of psychoanalysis were firm, and supported in an America that was much more open to them. According to a fellow Fortean and later editor of a revised version of the encyclopedia, Leslie Shepard, his views on the paranormal relaxed: he was no longer so intent on testing mediums under strict conditions, which he thought might inhibit their talents. In The Unaccountable, his late book on the subject and something of an autobiography, Fodor allowed that all manner of parapsychological phenomena were facts. Some, such as telepathy, could be very simple, or require deeply intimate and personal contact. Levitation occurred. But he offered no mechanism for these things—he left that to others, noting, for example, that deciphering the methods used by levitators could help in space travel. In this sense, Fodor obscured Fortean phenomena under another layer of mystery. He was still interested in the psychological manifestations of parapsychological forces.

During these last, more peaceful decades in America, Fodor composed a number of books classic in the field. In 1951, he and Carrington—with whom he had resumed his acquaintanceship—composed Haunted People: The Story of the Poltergeist down the Centuries. His magnum opus came out in 1959, The Haunted Mind: A Psychoanalyst Looks at the Supernatural. That book was published by Eileen Garrett, and Fodor also had a number of articles appear in her magazine, Tomorrow. There were other books, too—New Approaches to Dream Interpretation, On the Trail of the Poltergeist, Mind Over Space, Dictionary of Psychoanalysis, Between Two Worlds. He also had papers appear in a proper scientific journals.

Perhaps the most intriguing of his books was his third (after the Encyclopedia and a collection from his newspaper days, These Mysterious People.) In 1949, he published The Search For the Beloved: A Clinical Investigation of the Trauma of Birth and Pre-Natal Conditioning. The book concerned the telepathic connections between mother and the developing child within her, arguing that many later neuroses could be traced to this time—and defending the notion of maternal impressions: that shocking events to the mother could reveal themselves in the body of the child through a birthmark or other sign. Not incidentally, the book was put out by Hermitage Press which, a year later, published another science fiction-inflected book on psychology that made similar claims about prenatal trauma. That book was L. Ron Hubbard’s Diabetics: The Modern Science of Mental Health. One starts to see, through this connection, how the science fiction author and critic Thomas Disch dismissed Scientology as “debased Freudianism.”

There was a sense in which Fodor’s ideas updated the Romances he had read as a child. In The Unaccountable he wrote “Every object has a history, memories or dreams of the past that are stored and somehow become accessible to the one with the appropriate paranormal gift. How can a dead object have dreams? The answer is simple: Nothing that happens in this universe can perish. The world of reality created for us by our sensorium is a small one. In other dimensions other realities will unfold and we may yet discover that the only real world if the one we call today the world of dreams.”

But he also had a questing intellect, skeptical in ways that were often hidden by his enthusiasm and a simple credulity—a tidy and contradictory package that any psychoanalyst would enjoy unwrapping. So, on the one hand, he accepted human levitation and thought that it could be used to make space exploration economical—something straight out of those turn-of-the-century Romances—but on the other hand he could see that his very field of choice, psychoanalysis, was rooted in Jewish mysticism and the Kabbalah—a tradition very different from the New Thought and New Age religions that popped up in America during the nineteenth century but also parallel, as those were mystical versions of Christianity. His last book, published posthumously, explored the overlap between Freud and Jung and the occult.

Nandor Fodor died 17 May 1964.

Fodor obviously existed within a Fortean web—even if it would be wrong to reduce his interests to Fortean ones or to even say that he was a Fortean in any way beyond membership in the Society. He was surrounded by other, more committed Forteans; his degrees of separation from the Society were short; he shared interests—even obsessions—with Forteans, although he interpreted these in ways unusual for most Forteans about whom I know anything. It is fair to say that, like L. Ron Hubbard and many others, while not a Fortean—or not much of a Fortean—Fodor worked within a Fortean milieux.

It is unknown when Fodor first became aware of Fort. He does not warrant an entry in his Encyclopedia, nor was he mentioned in the discussion of poltergeist, which was a large area of overlap between Fodor and Fort. Indeed, it seems that Fodor and Fort’s thinking on poltergeists—in particular, connecting poltergeist activity to preadolescent and adolescent girls, in particular (but also other household antagonisms) developed in parallel: Fodor speculated along this line in Hereford Carrington’s 1930 The Story of Psychic Science. The first mention I see of Fort in Fodor’s work came in The Haunted People, which was co-authored with Carrington. They noted that Fort himself had experienced poltergeist activity, with pictures in his house falling inexplicably, as he reported in Wild Talents. He also briefly—and cryptically—mentioned Fort in The Unacknowledged: “Preposterous as Charles Fort’s presumption is that teleportation is Nature’s way of making a new distribution, a persistent study of psychic phenomena is bound to drive one to the conclusion that there is an occasional interplay of cosmic energies with human affairs which, through the unconscious as a receiving or transmitting station, plays blindman’s buff [sic] with us.”

Less direct, one can see Fort’s influence in Between Two Worlds, which was published the year that Fodor died. It is in many ways a Fortean compendium of unusual and occult phenomena. That book was taken up by contemporary and later Forteans—Vincent Gaddis mentioned it writing for the Borderlands Science Research Association (founded by N. Meade Layne) and Loren Coleman linked Fodor’s discussion in the book with Fort’s Wild Talents in the first issue of the Neo-Fortean journal The Anomalist. Others of Fodor’s work also percolated through the Fortean community. Haunted People was reviewed in the Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, by the “editors”—likely the Fortean Anthony Boucher, who did review another of Fodor’s book in the same magazine under his name, On the Trail of the Poltergeist. Hans Stefan Santesson, yet another Fortean science fiction author and editor, reviewed it in his magazine Fantastic Universe.

Fodor’s association with the Fortean Society dated back before any of that activity, though—that was the 1950s and 1960s, while his first mention in Doubt came in 1946. At that point, Thayer was already introducing him as a member (and noting that his fame came from the association with Gef the Talking Mongoose, one of Thayer’s favorite stories). There are a couple of ways Thayer may have reached out to Fodor (as I assume was the case). The less likely is through Harry Benjamin, the early sex researcher, who may have known Fodor through New York City’s psychoanalytical community—which was small, Jewish, and had a high number of ex-patriots. More likely, Thayer came to Fodor through Hereford Carrington. We know from letters that Thayer had met Carrington at least once, and, also, that Carrington was friends with the magician and Actor Fred Keating, who was close to Thayer during the 1930s and was a member of the Society. They had all three worked with the Boston medium Mina (Margery) Crandon. Given these connections, it is not hard to see why Thayer might have asked Fodor to join; given Fort’s Wild Talents, it is not hard to see why Fodor accepted.

Between that first mention in Doubt 14 (1946) and Doubt 28 (1950), Fodor’s name appeared a half-dozen times. All but one of these references came in the context of Thayer mentioning some writing by Fodor or another. The one exception was Doubt 21 (June 1948), in which Thayer noted the passing of Harry Price and said he was soliciting remembrances from Carrington and Fodor. If these ever came, they were not published in Doubt.

That first mention reported Fodor’s paper "Psychoanalytic Approach to the Problems of Occultism" was published in The Journal of Clinical Psychopathology. “Milestone in American psychics!,” Thayer crowed. N. Meade Layne, in the Borderlands Science Research Association’s Round Robin echoed, “Since the Pope turned Presbyterian, hardly an event more earth-shaking!" (And then went on to dog Thayer for his appreciation of Ezra Pound, but admit his Doubt was must-read.) This praise reflected the Fortean’s dilemma: one the one hand, they wanted to condemn mainstream science; on the other, they were delighted to finally be invited into the journals that guarded the mainstream.

This tension ran through a couple of the other Fodor mentions. In Doubt 16 Thayer praised Fodor’s “Lycanthropy as Psychic Mechanism,” which had been published in the Journal of American Folklore, for its ambiguity—its playfulness of criticizing conventional wisdom and accommodating it. On my reading of the paper, I don’t really see this coyness, but Thayer doffed his hat to Fodor: “Once again our admiration for Dr. Fodor’s choice of words is excited. He has completely mastered the technique of implying what the ‘believers‘ wish to read, without ever making a statement which a non-believer can assail. His tales of ladies-into-wolves and vice versa are interesting, but not half so entertaining as his semantics.”

In Doubt 24 (1949), Thayer noted that Fodor had caught the attention of science journalist John J. O’Neill with his paper “The Poltergeist—Psychoanalyzed” for the Psychiatric Quarterly. O’Neill found support from other experts that psychoanalytical techniques—even if not called that—had been used for a long time to lay spirits. The Society sold a reprint of the article in question. It would also sell autographed copies of The Search for the Beloved. Fodor provided those, just as he had provided the reprints and notice of his article on lycanthropy.

By the time that pre-Dianetics book came out, Thayer was no longer so amazed by Fodor’s verbal lability. “MFS Nandor Fodor--no stranger to these columns--has a new book of case histories, dream interpretation, psychoanalysis and psychiatry called The Search for the Beloved, ‘a clinical investigation of the trauma of birth and pre-natal conditioning, an important contribution toward the understanding of illness, anxiety and malfunction.’ Of the 32 chapters, 13 have appeared at various times in technical publications, but the terminology is readily understandable to the layman. One might wish that the findings were stated with a more truly Fortean reserve, but if allowance is made for the bad habit of certitude--necessary in the clinic to give ‘patients’ confidence--the material will bear study.” He further undermined Fodor with he illustration accompanying the announcement: A cartoon of Freud winding up a toy man that says ‘Long Live Pavlov.’ However, he could not resist noting that most of the cases were females—which fit in with his Fortean Law: Cherchez la Wonet.

The final mention went even farther to impugn the reliability of psychiatry—using Fodor as an example of someone who stood outside of the mainstream, which probably would not have made Fodor himself too happy: “MFS Fodor, sometimes associate of Hereward Carrington and of the late Harry Price, both celebrated investigators of psychic phenomena, sometime lecturer on the Talking Mongoose of Gashen’s Gap, Isle of Mann, (now thought to have been shot by a non-Fortean) has been on the air applying psychoanalysis to ‘popular songs’. We have not heard the show, but it afforded radio columnist John Crosby a chance to wheez, ‘Psyche me, Daddy, eight to the bar.’ And it brought out the social consciousness of radio columnist Harriet van Horne, thusly: ‘To my mind it does far more harm than good. Harm because it alienates reasonable but ill-informed people from the highly respectable branch of medicine that deals with the human mind and emotions. A bona fide psychiatrist, one feels certain, would not lend his name to this pedantic parlor game.’ Just how, and to whom, a ‘psychiatrist’ displays his bona fides is no part of radio reviewing, so La van Horne leaves that out, but goes on to weep--stuffily--for the national I.Q. We hesitate to enter debate with a lady on such a topic, but cannot refrain from advancing the counter opinion that every man, woman or child whom Nandor Fodor’s program keeps away from this ‘highly respectable branch of medicine’ will be better off than if they followed the current crazy rage to lie on a couch and tell all.”

“One measures a circle, beginning anywhere,” Fort famously wrote, and Thayer had come full circle now: he began by praising Fodor for getting noticed by the mainstream, and ended by hoping that Fodor would keep listeners away from psychoanalysis. For all the talk about female hormones and stuffy women, the real Freudian question that couldn’t be answered here is, What did Thayer want?

Breaking his father’s heart—the older man rightly predicted he would never again see his youngest son—Nandor migrated to the United States in 1921, where he was a journalist at the Hungarian-language American Hungarian People’s Voice. He would work as a journalist for more than a decade, but still valued his legal skills for letting him evaluate evidence: this is a common theme among investigators of the strange, trusting their bullshit detectors because of their training, particularly in journalism and law (since they are rarely trained in the sciences, and these are other professions concerned with the establishment of truths). While doing his work, he came across a book on parapsychology which recaptured the passion that Haggard and other writers of fantasy could no longer:

“If admiration is a kind of identification, I had identified myself with Macumazan of my youth.I am conscious, however, that I never wanted to become an explorer of unknown regions of the globe. Another outlet was presented to my devouring interest when I discovered the explorers of the unknown continents of the mind . . . I was seized by a burning curiosity and practically engraved on my mind every page, photograph and footnote. Here was something more promising than the darkest Africa, with adventures far more entrancing and of immense personal significance.”

The exact book he discovered is unclear. In his own account, Fodor has it as Cesar Lombroso’s After Death—What?, which had been published in 1909, at the end of the pioneering criminologist’s long life. Fodor’s follower (and fellow Fortean) Leslie Shepherd pegged the book as Hereford Carrington’s 1919 Modern Psychic Phenomena. Maybe it was at the Public Library on 42nd Street, maybe a Fourth Avenue bookstore. In either case, it wasn’t Fort—although he may have come across Fort’s first, The Book of the Damned, which was published in 1919 (with a street date of 1920) as he became addicted to the topic, eating only coffee and a cinnamon bun for lunch (rather than at the many surrounding Hungarian restaurants) to save money for books.

Fodor married in 1922, another Hungarian, Amaira Iren (Irene); a few years his junior, she had been in the States since 1912. But his obsession continued— “I remember—to my shame as a young husband—reading int late into the night after she had gone to bed,” he wrote in 1959. The two must have connected some time, though, since Irene gave birth to Andres in April 1923. In the course of his research, he met Carrington himself, who introduced Fodor to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Shepherd believes that Fodor took Carrington as a model. In 1926, Fodor met another man who would have a profound effect on his life, the Hungarian ex-patriot and psychoanalyst Sandor Ferenczi. By this time, his father had passed, and Fodor seemed intent to make America his home, applying for naturalization.

Fodor became a spiritualist. He saw that there was a lot of interest in the subject—Scientific American was offering cash money for definitive proof—and he was able to see stories on spiritualism to English language outlets. He attended seances, and at one of them heard from his dead father. He was young and naive at the time, by his own admission, and credulous, but that moment would remain with him as one of three times in his entire four-decade career that he had undeniable proof of life after death: and that was enough to commit him to spiritualism. He didn’t buy all spiritualist thought, though, and that was the seed of an eventual split.

For reasons unclear, the Fodor family relocated to England in 1928; probably it had to do with work. Around this time he interviewed the newspaper magnate Lord Rothermere (Harold Harmsworth). Lord Rothermere had little interest in Spiritualism, but was intent on making his papers widely popular, and Fodor had gained a reputation for punchy prose—at least by his own account—which may have owed something to his learning the language from writers of fantasy. There was also a political connection. Rothermere wanted to lighten the burden of World War I treaties on Hungary, a cause that was also close to the heart of Fodor. (According to Wikipedia, Rothermere was motivated less by beneficence and more by a mistress and hope that he might become a royal there.) Fodor became Rothermere’s secretary, in charge of Hungarian affairs. If I am correct about Fodor’s heritage, then his brother was also involved in politics around this time, legal consultant for a Zionist movement.

There was an active Spiritualist movement in London, and Fodor soon attached himself to it. Fodor was taken by H.G. Wells The Science of Life when it appeared in 1931—the same year as Fort’s Lo!—and reviewed the skeptical chapter on life after death for Life, the weekly magazine of the London Spiritualist Alliance, concluding, “Whether for serious study or to draw ideas of association for his brilliantly fertile mind, he would be welcome among psychic investigators. Let him come to scoff. He may remain to pray.” (Wells was an interest of other Forteans, too: Dreiser tried to convert him to the Society; Alexander Woollcott was amazed by The Science of Life, and Kenneth Rexroth considered Wells’s Research Magnificent one of his lodestars.) Trying to make sense of all that he was reading, Fodor had been indexing the material and in the early 1930s put out—with a London publisher—The Encyclopedia of Psychic Science. Around the same time, he was appointed assistant editor of Light. Half-a-century old now, the magazine had become stodgy and with another newspaperman he was brought on board to give it new life. In 1936, he became the London correspondent for the Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research.

He also became a research officer with the International Institute for Psychical Research, and had some unsatisfying psychic experiences. He tried to contact Lord Rothermere’s dead brother, Lord Northcliffe, which lead to nothing. He also spent months waiting for a spirit to guide him in automatic writing. His wife—an artist and, he reckoned, generally more sensitive—felt the impulse but produced nothing of note. The spirit never moved him though. The “chasing a will-o’-the-wisp, perhaps my most fascinating adventure, the best illustration of the utterly stupid and imbecilic length to which a believer allows himself to be carried.” He investigated Gef The Talking Mongoose (yes, mongoose), which supposedly haunted a farm on the Isle of Man (later a center of English witchcraft) and came away convinced that it was, of anything, a hoax—although one that fit with his developing theories about psychic phenomena.

The 1930s saw Fodor making two connections that allowed him to overcome his naiveté. The first was meeting another future Fortean, the medium Eileen Garrett, who was being studied by a number of spiritualist researchers, among them Hereward Carrington. Garrett was, by the account of all the spiritualists she knew, a gifted trance medium. But she herself doubted whether the so-called controls who spoke through her were really spirits—indeed, she spent her whole life wrestling with this question. Fodor was impressed by this line of thinking. He wondered, as Garrett did herself, if these controls, these spirits, were some form of subconscious manifestation, a secondary personality, perhaps. He noted that her main control, Uvani, never claimed to speak to Fodor’s father during their seances, but reported information Garrett may have picked up from his mind—perhaps, then, it was ESP or telepathy (just like in the Alan Quartermain books!) and not contact with the other side at all.

These musings took more coherent form after the second connection, with Elizabeth Severn, a student of Ferenczi, and so a psychoanalyst only once removed from Freud himself. Fodor began studying psychoanalysis rigorously. He came to think that, perhaps, many mediums were in contact with the collective unconscious, that the voices they heard were archetypes: the Eastern Masters, for example, just versions of the wise man. Garrett influenced him here, too. She was known to “lay ghosts”—to calm hauntings and poltergeists—by diagnosing the psychological disturbances in the family, and he did similarly. He told a story of helping a homicidal man not by dismissing the voices he heard but by subtly altering them, such that they became positive, the man helpful. The last Fodor heard of him, he was a dog whisperer, helping befuddled owners understand their canines.

The turn to psychoanalysis was one way around the Spiritualist’s constant conundrum: that every phenomena was either a hoax or proof of life after death. For Fodor, even hoaxes became worthy of study, because they opened a window into the psychology of the (fake) medium. That psychoanalysis, with its focus on sex, was the key to understanding this psychology was proved beyond a shadow of a doubt to him when one of the frauds he unveiled was shown to secret the objects she claims dot psychically materialize in her vagina. Girls near menarche became a special focus of his research: relying on the gender stereotypes of the day, they were seen as especially volatile and likely to cause poltergeist activities, often subconsciously. Fort had made similar points in Wild Talents and the Forteans would take up the idea ironically with their interest in “Wonets.”

Other spiritualists were not so pleased with Fodor’s turn toward psychoanalysis—nor were all of Freud’s disciples pleased with the connection. The history here, though, is more complicated than Fodor had it. Psychoanalysis had long been intertwined with studies of the paranormal in Britain—it came to the public’s attention first through the writings of Frederic Myers, founder of the Society for Psychical Research. Since that time, though, some Freudians had tried to disentangle the two, worried that association with psychical research would make their science seem fringe, while some psychical researchers turned to psychoanalysis exactly because it seemed to give their own studies a scientific cachet. At the same time, there were psychoanalysts who continued to probe the psychical without worrying over reputation. A tension, then, within the two, overlapping fields, as workers from both sides tried to connect them, and others sever the connections.

Fodor felt particularly exposed, and seemed to draw the ire of many psychical researchers. In the mid-1930s, he had committed to living in the London area—his American naturalization file contains a letter from him acknowledging he had left the U.S. less than five years after he was naturalized and did not plan on returning, making that naturalization null and void. Yet the English spiritualists publicly attacked him for his turn to psychoanalysis and bringing in the subject of sex. There was much public back and forth, and even a lawsuit. In 1938, Irene brought one of Fodor’s manuscripts connecting psychical research and psychoanalysis to Freud, who was then living in London, exiled by the rise of Nazism. Fodor was much buoyed when he received a letter of support from Freud praising his research.

However supported he might have finally felt with Freud’s acknowledgment, Fodor wasn't long for Britain. He returned to America in spring 1939—I’m not sure why—and another Fortean connection. While they settled, Nandor and Irene stayed with Ben Hecht’s first wife, Marie Armstrong Essipoff. Apparently she had (or had developed) an interest in the outré. During the 1950s she would claim to see a UFO, for example. And at the time, she and Fodor tried table turning, though without success. Eventually, Fodor opened a psychoanalytic practice and settled down making his living that way. He also continued his investigations and writing on parapsychology.

His views on the importance of psychoanalysis were firm, and supported in an America that was much more open to them. According to a fellow Fortean and later editor of a revised version of the encyclopedia, Leslie Shepard, his views on the paranormal relaxed: he was no longer so intent on testing mediums under strict conditions, which he thought might inhibit their talents. In The Unaccountable, his late book on the subject and something of an autobiography, Fodor allowed that all manner of parapsychological phenomena were facts. Some, such as telepathy, could be very simple, or require deeply intimate and personal contact. Levitation occurred. But he offered no mechanism for these things—he left that to others, noting, for example, that deciphering the methods used by levitators could help in space travel. In this sense, Fodor obscured Fortean phenomena under another layer of mystery. He was still interested in the psychological manifestations of parapsychological forces.

During these last, more peaceful decades in America, Fodor composed a number of books classic in the field. In 1951, he and Carrington—with whom he had resumed his acquaintanceship—composed Haunted People: The Story of the Poltergeist down the Centuries. His magnum opus came out in 1959, The Haunted Mind: A Psychoanalyst Looks at the Supernatural. That book was published by Eileen Garrett, and Fodor also had a number of articles appear in her magazine, Tomorrow. There were other books, too—New Approaches to Dream Interpretation, On the Trail of the Poltergeist, Mind Over Space, Dictionary of Psychoanalysis, Between Two Worlds. He also had papers appear in a proper scientific journals.

Perhaps the most intriguing of his books was his third (after the Encyclopedia and a collection from his newspaper days, These Mysterious People.) In 1949, he published The Search For the Beloved: A Clinical Investigation of the Trauma of Birth and Pre-Natal Conditioning. The book concerned the telepathic connections between mother and the developing child within her, arguing that many later neuroses could be traced to this time—and defending the notion of maternal impressions: that shocking events to the mother could reveal themselves in the body of the child through a birthmark or other sign. Not incidentally, the book was put out by Hermitage Press which, a year later, published another science fiction-inflected book on psychology that made similar claims about prenatal trauma. That book was L. Ron Hubbard’s Diabetics: The Modern Science of Mental Health. One starts to see, through this connection, how the science fiction author and critic Thomas Disch dismissed Scientology as “debased Freudianism.”

There was a sense in which Fodor’s ideas updated the Romances he had read as a child. In The Unaccountable he wrote “Every object has a history, memories or dreams of the past that are stored and somehow become accessible to the one with the appropriate paranormal gift. How can a dead object have dreams? The answer is simple: Nothing that happens in this universe can perish. The world of reality created for us by our sensorium is a small one. In other dimensions other realities will unfold and we may yet discover that the only real world if the one we call today the world of dreams.”

But he also had a questing intellect, skeptical in ways that were often hidden by his enthusiasm and a simple credulity—a tidy and contradictory package that any psychoanalyst would enjoy unwrapping. So, on the one hand, he accepted human levitation and thought that it could be used to make space exploration economical—something straight out of those turn-of-the-century Romances—but on the other hand he could see that his very field of choice, psychoanalysis, was rooted in Jewish mysticism and the Kabbalah—a tradition very different from the New Thought and New Age religions that popped up in America during the nineteenth century but also parallel, as those were mystical versions of Christianity. His last book, published posthumously, explored the overlap between Freud and Jung and the occult.

Nandor Fodor died 17 May 1964.

Fodor obviously existed within a Fortean web—even if it would be wrong to reduce his interests to Fortean ones or to even say that he was a Fortean in any way beyond membership in the Society. He was surrounded by other, more committed Forteans; his degrees of separation from the Society were short; he shared interests—even obsessions—with Forteans, although he interpreted these in ways unusual for most Forteans about whom I know anything. It is fair to say that, like L. Ron Hubbard and many others, while not a Fortean—or not much of a Fortean—Fodor worked within a Fortean milieux.

It is unknown when Fodor first became aware of Fort. He does not warrant an entry in his Encyclopedia, nor was he mentioned in the discussion of poltergeist, which was a large area of overlap between Fodor and Fort. Indeed, it seems that Fodor and Fort’s thinking on poltergeists—in particular, connecting poltergeist activity to preadolescent and adolescent girls, in particular (but also other household antagonisms) developed in parallel: Fodor speculated along this line in Hereford Carrington’s 1930 The Story of Psychic Science. The first mention I see of Fort in Fodor’s work came in The Haunted People, which was co-authored with Carrington. They noted that Fort himself had experienced poltergeist activity, with pictures in his house falling inexplicably, as he reported in Wild Talents. He also briefly—and cryptically—mentioned Fort in The Unacknowledged: “Preposterous as Charles Fort’s presumption is that teleportation is Nature’s way of making a new distribution, a persistent study of psychic phenomena is bound to drive one to the conclusion that there is an occasional interplay of cosmic energies with human affairs which, through the unconscious as a receiving or transmitting station, plays blindman’s buff [sic] with us.”

Less direct, one can see Fort’s influence in Between Two Worlds, which was published the year that Fodor died. It is in many ways a Fortean compendium of unusual and occult phenomena. That book was taken up by contemporary and later Forteans—Vincent Gaddis mentioned it writing for the Borderlands Science Research Association (founded by N. Meade Layne) and Loren Coleman linked Fodor’s discussion in the book with Fort’s Wild Talents in the first issue of the Neo-Fortean journal The Anomalist. Others of Fodor’s work also percolated through the Fortean community. Haunted People was reviewed in the Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, by the “editors”—likely the Fortean Anthony Boucher, who did review another of Fodor’s book in the same magazine under his name, On the Trail of the Poltergeist. Hans Stefan Santesson, yet another Fortean science fiction author and editor, reviewed it in his magazine Fantastic Universe.

Fodor’s association with the Fortean Society dated back before any of that activity, though—that was the 1950s and 1960s, while his first mention in Doubt came in 1946. At that point, Thayer was already introducing him as a member (and noting that his fame came from the association with Gef the Talking Mongoose, one of Thayer’s favorite stories). There are a couple of ways Thayer may have reached out to Fodor (as I assume was the case). The less likely is through Harry Benjamin, the early sex researcher, who may have known Fodor through New York City’s psychoanalytical community—which was small, Jewish, and had a high number of ex-patriots. More likely, Thayer came to Fodor through Hereford Carrington. We know from letters that Thayer had met Carrington at least once, and, also, that Carrington was friends with the magician and Actor Fred Keating, who was close to Thayer during the 1930s and was a member of the Society. They had all three worked with the Boston medium Mina (Margery) Crandon. Given these connections, it is not hard to see why Thayer might have asked Fodor to join; given Fort’s Wild Talents, it is not hard to see why Fodor accepted.

Between that first mention in Doubt 14 (1946) and Doubt 28 (1950), Fodor’s name appeared a half-dozen times. All but one of these references came in the context of Thayer mentioning some writing by Fodor or another. The one exception was Doubt 21 (June 1948), in which Thayer noted the passing of Harry Price and said he was soliciting remembrances from Carrington and Fodor. If these ever came, they were not published in Doubt.

That first mention reported Fodor’s paper "Psychoanalytic Approach to the Problems of Occultism" was published in The Journal of Clinical Psychopathology. “Milestone in American psychics!,” Thayer crowed. N. Meade Layne, in the Borderlands Science Research Association’s Round Robin echoed, “Since the Pope turned Presbyterian, hardly an event more earth-shaking!" (And then went on to dog Thayer for his appreciation of Ezra Pound, but admit his Doubt was must-read.) This praise reflected the Fortean’s dilemma: one the one hand, they wanted to condemn mainstream science; on the other, they were delighted to finally be invited into the journals that guarded the mainstream.

This tension ran through a couple of the other Fodor mentions. In Doubt 16 Thayer praised Fodor’s “Lycanthropy as Psychic Mechanism,” which had been published in the Journal of American Folklore, for its ambiguity—its playfulness of criticizing conventional wisdom and accommodating it. On my reading of the paper, I don’t really see this coyness, but Thayer doffed his hat to Fodor: “Once again our admiration for Dr. Fodor’s choice of words is excited. He has completely mastered the technique of implying what the ‘believers‘ wish to read, without ever making a statement which a non-believer can assail. His tales of ladies-into-wolves and vice versa are interesting, but not half so entertaining as his semantics.”

In Doubt 24 (1949), Thayer noted that Fodor had caught the attention of science journalist John J. O’Neill with his paper “The Poltergeist—Psychoanalyzed” for the Psychiatric Quarterly. O’Neill found support from other experts that psychoanalytical techniques—even if not called that—had been used for a long time to lay spirits. The Society sold a reprint of the article in question. It would also sell autographed copies of The Search for the Beloved. Fodor provided those, just as he had provided the reprints and notice of his article on lycanthropy.

By the time that pre-Dianetics book came out, Thayer was no longer so amazed by Fodor’s verbal lability. “MFS Nandor Fodor--no stranger to these columns--has a new book of case histories, dream interpretation, psychoanalysis and psychiatry called The Search for the Beloved, ‘a clinical investigation of the trauma of birth and pre-natal conditioning, an important contribution toward the understanding of illness, anxiety and malfunction.’ Of the 32 chapters, 13 have appeared at various times in technical publications, but the terminology is readily understandable to the layman. One might wish that the findings were stated with a more truly Fortean reserve, but if allowance is made for the bad habit of certitude--necessary in the clinic to give ‘patients’ confidence--the material will bear study.” He further undermined Fodor with he illustration accompanying the announcement: A cartoon of Freud winding up a toy man that says ‘Long Live Pavlov.’ However, he could not resist noting that most of the cases were females—which fit in with his Fortean Law: Cherchez la Wonet.

The final mention went even farther to impugn the reliability of psychiatry—using Fodor as an example of someone who stood outside of the mainstream, which probably would not have made Fodor himself too happy: “MFS Fodor, sometimes associate of Hereward Carrington and of the late Harry Price, both celebrated investigators of psychic phenomena, sometime lecturer on the Talking Mongoose of Gashen’s Gap, Isle of Mann, (now thought to have been shot by a non-Fortean) has been on the air applying psychoanalysis to ‘popular songs’. We have not heard the show, but it afforded radio columnist John Crosby a chance to wheez, ‘Psyche me, Daddy, eight to the bar.’ And it brought out the social consciousness of radio columnist Harriet van Horne, thusly: ‘To my mind it does far more harm than good. Harm because it alienates reasonable but ill-informed people from the highly respectable branch of medicine that deals with the human mind and emotions. A bona fide psychiatrist, one feels certain, would not lend his name to this pedantic parlor game.’ Just how, and to whom, a ‘psychiatrist’ displays his bona fides is no part of radio reviewing, so La van Horne leaves that out, but goes on to weep--stuffily--for the national I.Q. We hesitate to enter debate with a lady on such a topic, but cannot refrain from advancing the counter opinion that every man, woman or child whom Nandor Fodor’s program keeps away from this ‘highly respectable branch of medicine’ will be better off than if they followed the current crazy rage to lie on a couch and tell all.”

“One measures a circle, beginning anywhere,” Fort famously wrote, and Thayer had come full circle now: he began by praising Fodor for getting noticed by the mainstream, and ended by hoping that Fodor would keep listeners away from psychoanalysis. For all the talk about female hormones and stuffy women, the real Freudian question that couldn’t be answered here is, What did Thayer want?