An artistic Fortean.

Martha Hamlin was born, 1906, in Buffalo, New York, to Chauncey J. and Emily Gray Hamlin. They were a rich family with deep roots in the region. Martha went to France in her teens, where she developed an interest in art. In 1922, she studied Académie Julian, in Paris. Through the 1920s, she traveled back and forth between Europe and New York City, taking some time to study stage design (at the Parson’s School of Applied Art, in New York), collecting art by the likes of Modigliani and Chagall, and running with other modernist painters, including Picasso. She was especially connected to the Russian expatriate scene, and had an affair with Boris Grigoriev.

In 1928, still in her early twenties, Hamlin moved back to Buffalo; she and her sister soon enough departed for Taos, New Mexico, where the circulated in the Bohemian culture there, meeting Georgia O’Keefe and making a pilgrimage to Diego Rivera. Her sister would settle there, in New Mexico. Martha, though, returned to Buffalo, where she married Franciscus Visser’t Hooft, a Dutch chemist; they had three children. Raising a family, knuckling under to demands from her husband, and meeting social obligations put a crimp in Visser’t Hooft’s artistic ambitions. She did do local work, joining the Buffalo Society of Artists and, later, founding the Patteran Society, which was a progressive alternative to the Buffalo Society of Artists.

Martha Hamlin was born, 1906, in Buffalo, New York, to Chauncey J. and Emily Gray Hamlin. They were a rich family with deep roots in the region. Martha went to France in her teens, where she developed an interest in art. In 1922, she studied Académie Julian, in Paris. Through the 1920s, she traveled back and forth between Europe and New York City, taking some time to study stage design (at the Parson’s School of Applied Art, in New York), collecting art by the likes of Modigliani and Chagall, and running with other modernist painters, including Picasso. She was especially connected to the Russian expatriate scene, and had an affair with Boris Grigoriev.

In 1928, still in her early twenties, Hamlin moved back to Buffalo; she and her sister soon enough departed for Taos, New Mexico, where the circulated in the Bohemian culture there, meeting Georgia O’Keefe and making a pilgrimage to Diego Rivera. Her sister would settle there, in New Mexico. Martha, though, returned to Buffalo, where she married Franciscus Visser’t Hooft, a Dutch chemist; they had three children. Raising a family, knuckling under to demands from her husband, and meeting social obligations put a crimp in Visser’t Hooft’s artistic ambitions. She did do local work, joining the Buffalo Society of Artists and, later, founding the Patteran Society, which was a progressive alternative to the Buffalo Society of Artists.

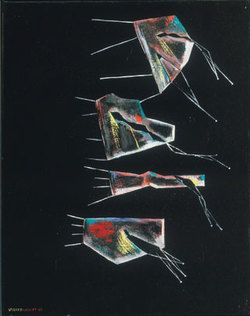

Fall of Related Objects: Tribute to Charles Fort (1948)

Fall of Related Objects: Tribute to Charles Fort (1948) In the late 1940s, about two decades into her marriage, Visser’t Hooft began focusing on her own work. She wrote a short manifesto in 1946, which I have not seen, but one article quotes a line: "I paint instead of leaping out of high windows." There was clearly a lot of angst built into her art. She worked in the tradition of surrealism, and abstract expressionism. Thirty years later, she would summarize what she was trying to do: “In my paintings I create situation and images beyond the realm of the possible. I invite the mind and the eye into a totally new experience.” Her work at this time was associated with Contemporary Arts Gallery in New York, where it was exhibited.

By the 1960s, she was moving from regional renown to wider acceptance. She had the wherewithal to visit Taos again, early in the decade, and her works found there way into the Whitney and the Met, with reviews in mainstream publications. She had a retrospective in the 1970s, and in the 1980s did some work with the poet Robert Creeley. A review of a 1992 retrospective said, “One rule is always followed: Any items borrowed from the real world are to be trans-formed. Certain rickety Visser't Hooft objects seem ancient, looking as though they carry the weight of human history on their fragile frames. Even rocks and birds take on human feelings, and buildings buzz with a secret emotional life. No wonder many Visser't Hooft inventions are given legs. They are anxious objects not quite sure what will confront them next. They may need to scurry away at any moment.”

She continued to paint very late in life. Martha Visser’t Hooft died 9 March 1994. She was 87.

**********************

Exactly how Visser’t Hooft discovered Fort is not known; it may have been through Buffalo Forteans. There were a few: Knute W. Golde, a piano repairman; Harold W. Giles, a bookseller; and a Ms. Goldstein, who may have been a teacher. More likely, she came across a reference to Fort in her artistic circles. Fort was known among surrealist writers, such as Philip Lamantia, and in the modernist art scene, as represented, on the West Coast, by those associated with “Circle” magazine. He would be discussed more fully later, in the 1960s and after, as surrealists looked back on influences, but it seems very likely that he was a topic of conversation in the 1940s, too, after the publication of his omnibus. Of course, that could have been another route of discovery—Visser’t Hooft might have seen a review or mention of Fort in some popular periodical and hunted down his book on her own.

Exactly when she discovered Fort is also unknown. The brief remarks on her manifesto make it seem, though, that either she had already read him—or that she was thinking along similar lines. The article notes, “She likened painting to leaping because painting, to be good, had to be risky. Unlike leaping, which tends to be a one-time thing, painting can be repeated over and over. Being an act of the imagination, it can even defy gravity. As the artist phrased it, it can allow one to ‘fall upwards.’”

One of the paintings from the beginning of this period—when she was using the vocabulary of surrealism and cubism—deals with weird falls, and is explicitly Fortean. It is called “Fall of Related Objects: Tribute to Charles Fort” and was finished in 1948. The painting, done in oil on canvas, is abstract in the extreme, with no identifiable figures. It is not even immediately clear what is falling.

There are four larger, possibly legged, geometric figures, stacked on top of one another against a black field. Is these things which are falling? They are related in their size, their shape, and the patchy colors distributed over them. And the black field ha a few, scattered white dots, like stars. But in what way are they falling? Their legs—if that is what they are, four sticks—point to the side, as though the painting has been placed in the wrong direction.

Or, perhaps those are not legs—but something like jet thrusters. And what is falling are, instead, smaller black shapes against the colored one. These are reminiscent of that most Fortean of falling objects, frogs, with long, gracile legs. But then the question becomes: how are they falling? Are they being distorted from space ships—freighters on the Super-Sargasso Sea—into the blackness of space? Or are they falling from the blackness into geometrically shaped holes: the piercings in the gelatinous shell that Fort said surrounded the earth and people mistakenly thought were stars. Are the colors earth? It is a disorienting piece.

I have not seen much else by Visser’t Hooft, but a few pieces from just slightly later in this period such a continued affinity for Fort: “Fish in a Bottle” (1949), with its suggestion of a human aquarium and people being fished for and “Medium’s Table” (1952), for example, with its invocation of spiritualist practice. But at this point, it is just speculation.

Further investigation of the connection between Forteanism and Martha Visser’t Hooft would probably pay off—but for the time being, she’s a solid link between Fort, the Forteans, and the world of modern art.

By the 1960s, she was moving from regional renown to wider acceptance. She had the wherewithal to visit Taos again, early in the decade, and her works found there way into the Whitney and the Met, with reviews in mainstream publications. She had a retrospective in the 1970s, and in the 1980s did some work with the poet Robert Creeley. A review of a 1992 retrospective said, “One rule is always followed: Any items borrowed from the real world are to be trans-formed. Certain rickety Visser't Hooft objects seem ancient, looking as though they carry the weight of human history on their fragile frames. Even rocks and birds take on human feelings, and buildings buzz with a secret emotional life. No wonder many Visser't Hooft inventions are given legs. They are anxious objects not quite sure what will confront them next. They may need to scurry away at any moment.”

She continued to paint very late in life. Martha Visser’t Hooft died 9 March 1994. She was 87.

**********************

Exactly how Visser’t Hooft discovered Fort is not known; it may have been through Buffalo Forteans. There were a few: Knute W. Golde, a piano repairman; Harold W. Giles, a bookseller; and a Ms. Goldstein, who may have been a teacher. More likely, she came across a reference to Fort in her artistic circles. Fort was known among surrealist writers, such as Philip Lamantia, and in the modernist art scene, as represented, on the West Coast, by those associated with “Circle” magazine. He would be discussed more fully later, in the 1960s and after, as surrealists looked back on influences, but it seems very likely that he was a topic of conversation in the 1940s, too, after the publication of his omnibus. Of course, that could have been another route of discovery—Visser’t Hooft might have seen a review or mention of Fort in some popular periodical and hunted down his book on her own.

Exactly when she discovered Fort is also unknown. The brief remarks on her manifesto make it seem, though, that either she had already read him—or that she was thinking along similar lines. The article notes, “She likened painting to leaping because painting, to be good, had to be risky. Unlike leaping, which tends to be a one-time thing, painting can be repeated over and over. Being an act of the imagination, it can even defy gravity. As the artist phrased it, it can allow one to ‘fall upwards.’”

One of the paintings from the beginning of this period—when she was using the vocabulary of surrealism and cubism—deals with weird falls, and is explicitly Fortean. It is called “Fall of Related Objects: Tribute to Charles Fort” and was finished in 1948. The painting, done in oil on canvas, is abstract in the extreme, with no identifiable figures. It is not even immediately clear what is falling.

There are four larger, possibly legged, geometric figures, stacked on top of one another against a black field. Is these things which are falling? They are related in their size, their shape, and the patchy colors distributed over them. And the black field ha a few, scattered white dots, like stars. But in what way are they falling? Their legs—if that is what they are, four sticks—point to the side, as though the painting has been placed in the wrong direction.

Or, perhaps those are not legs—but something like jet thrusters. And what is falling are, instead, smaller black shapes against the colored one. These are reminiscent of that most Fortean of falling objects, frogs, with long, gracile legs. But then the question becomes: how are they falling? Are they being distorted from space ships—freighters on the Super-Sargasso Sea—into the blackness of space? Or are they falling from the blackness into geometrically shaped holes: the piercings in the gelatinous shell that Fort said surrounded the earth and people mistakenly thought were stars. Are the colors earth? It is a disorienting piece.

I have not seen much else by Visser’t Hooft, but a few pieces from just slightly later in this period such a continued affinity for Fort: “Fish in a Bottle” (1949), with its suggestion of a human aquarium and people being fished for and “Medium’s Table” (1952), for example, with its invocation of spiritualist practice. But at this point, it is just speculation.

Further investigation of the connection between Forteanism and Martha Visser’t Hooft would probably pay off—but for the time being, she’s a solid link between Fort, the Forteans, and the world of modern art.