Collage of Lilith Lorraine at various ages from Cleveland Lamar Wright's "The Story of Avalon."

Collage of Lilith Lorraine at various ages from Cleveland Lamar Wright's "The Story of Avalon." Lilith Lorraine went by many names, so many it is not even easy to identify her birth name. The conventional sources have her born 19 March 1894 and give her name then as Mary Maud Dunn. None of this information, though—as far as I can tell—come from contemporary documents: birth certificates, newspaper announcements, etc. Her birthdate is given on her death certificate and, while she was alive, she did say that her birth name was “Mary Maud.” Probably this is true, but in the 1900 and 1910 censuses she went only by Maud or Maude.

She was the only child of John Beamon Dunn and Lelia Nias. Maud descended from what amounts to royalty in Corpus Christi, Texas; her paternal grandfather had been one of the first settlers, of the area, having migrated from Ireland, and her father was a Texas Ranger and cattleman. In 1932, Lilith—lets call her that for simplicity—would edit his memoirs, Perilous Trails of Texas. “Red” Dunn, as her father was nicknamed, collected Corpus Christi memorabilia, which he donated to a local museum, after he had spent years displaying it.

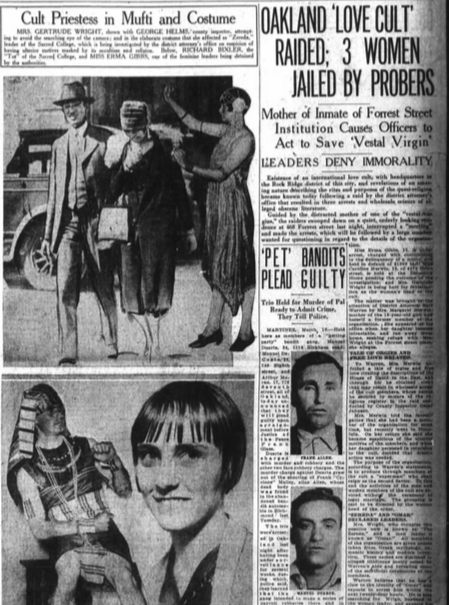

"Gertrude" Wright, 1927.

"Gertrude" Wright, 1927. Which seems inconsistent with the marriage date given in The Handbook of Texas as 21 April 1912. At that point, Lorraine would have just turned 18, and Cleveland would have been around 24 (his World War I draft card notes he was unsure of his exact birth date). Perhaps Texas schools released early in spring at that time, I’m not sure. All I know is I have not been able to get an official record of the marriage date. No reason not to believe the date is wrong—but nothing form proving it, either. Cleveland had been raised a Baptist and so the couple split the difference by being married by a Methodist—minus the pledge to obey, he notes. The religious syncretism and independence suggested by the ceremony foreshadowed events to come.

Three months later—again according to Cleveland—he and Lilith sat “on the front steps of our little cottage among the live oaks engaged in our favorite pastime of watching the constellations above and the fire-flies spread out like a moving blanket of flame below.” He mentioned that he had actually pledged his love to some one else, in a grand romantic gesture. While riding along a road, his horse had spooked at a wind-blown scrap of paper. Cleveland had retrieved it, and read a school-girl’s poem that “opened . . . . a door . . . somewhere in space” so that “for a moment I saw life as a whole. had become as a god. I knew then that all the fairy tales were true and all else was lies. That was the way love came to me.” He “made up my mind at that moment to find and marry the author of that poem.” The ruled page from a copy book read

“The Greater Love

There’s a love that pierces further than the ultimate reach of light,

There’s a love that soareth freer than the swiftest seraph’s flight,

There’s a love of rainbow splendor gleaming in uncharted skies,

There a love that flames in chaos when the tired immortals find

Rest in dim Nirvanic spaces from the ceaseless strife of mind.

There’s a love that builds in darkness, shaping heavens ever new

From the wreck of lesser passions; that’s the love I have for you.

P.S. Imagine writing this romantic stuff at the age of ten.”

Cleveland showed the poem to Lilith, who laughed. She herself had written the poem. She had been writing poetry since the age of 7, she would claim throughout her life, and memorized Shakespeare’s sonnets before the age of 10. This particular poem she had sent to a nearby friend, who had lost it—and Cleveland had found it. Such was the way miracles worked for them. As he remembered Lilith telling him that night, “Most miracles are simple and reasonable. Coincidences are often the most perfect alibis of the Invisible Powers. Let’s not destroy their defense mechanisms.”

Fuzzy as it is—and hard to believe—Lilith’s life becomes fuzzier and more unbelievable over the next several years. Her late admirer, the poet Steven Sneyd, who has tried to piece together a biography of her life, notes that many of the pieces are hard to fit together and that her doings in the 1920s are especially difficult to suss out. That’s true, and I think I have found a large part of the reason—as was her wont, she was going by another name.

The Handbook of Texas, as other biographical sources—including newspaper reports that described her in the 1950s and 1960s, after she had achieved a certain amount of fame and acclaim—note that she moved to the San Francisco Bay Area around 1920 and became a police writer (and columnist) for the San Francisco Examiner and other Hearst papers. I have never actually seen any of this articles, and no one cites specific ones, so it is hard to know if it is true. But she did end up in the San francisco Bay Area during this time. (Incidentally, the later Fortean and founder of the Church of Satan, Anton LaVey, also made a contested claim that he was a crime reporter in San Francisco before coming to prominence.)

The evidence here gets complicated, and it’s necessary to abandon simple narrative and start talking historical detective work. The key here is Cleveland. As Sneyd notes, Cleveland shows up in Bay Area records from this time as an instructor of conductors and motormen, but the directories do not seem to list Mary. This is a simplification: there were actually two other Cleveland Wrights in the area at the time that I found, Cleveland R., a lawyer, who is in the area before and after the 1920s, and another Cleveland, a salesman, who is married to a Mary. They lived at 710 Ellis Street, in San Francisco, which is the key to determining this is not our Cleveland and Mary: a World War II draft card reveals that the Cleveland Wright of 710 Ellis Street was actually Ely Cleveland Wright.

The Cleveland Lamar Wright, born in Texas, and a conductor, does appear in several 1927 newspapers—more on these articles in a moment!—but his wife’s name is given as Gertrude. (I only came across these because I was looking up variants of Cleveland’s name in old newspapers). As it happens, the 1920 census has a Cleveland and Gertrude Wright living in San Antonio in 1920, where he worked as a conductor of streetcars and she was a stenographer for an oil company. They are both listed as Texas natives, with parents from Texas. Cleveland is aged 33 and Gertrude 24, these as of 22 January 1920. His age maps perfectly, while Gertrude’s is two years off from what we think we know of Mary. Given that we don’t actually have official records for Mary’s birth, and the scrubbing away of two years wouldn’t be especially surprising anyway, I don’t put too much weight on this disparity.

There is some possible confusion when it comes to the Bay Area, as there seem to have been several Gertrude Wrights in the region—not surprising, given that neither the Christian name nor the surname are particularly rare. And one was even a stenographer who lived near an area where our Gertrude was known to frequent—the only discordant note here is that the name appears in the 1930 directory, after Lilith was gone. That could be coincidence or a fluke of publishing. Set it aside, either way, because when factual nuggets are pulled out of the series of 1927 articles, it is clear that this Gertrude Wright and this Cleveland Wright are the ones in question:

*Both are said to come from Corpus Christi and San Antonio, Texas

*Gertrude is said to have a prominent family; Cleveland had family in Falfurrias.

*Cleveland L—his middle name is not specified—is a conductor of streetcars.

*Gertrude is said to be a poet.

*Gertrude and Cleveland had been married for 13 years.

*Gertrude was thirty years old—which accords with the 1920 census.

*Her father’s name is John Dunn.

*The pictures of Gertrude Wright look an awful lot like a young Lilith Lorraine.

*Sneyd got his hands on Lilith’s FBI file. (I tried, but was told it had been destroyed.) The file mentioned that Lilith had been charged with contributing to the delinquency of a minor and skipping bail for Mexico—so seemingly at odds with what was known of Lorraine that Sneyd was reluctant to believe it. As it happens, this Gertrude was, indeed, charged with contributing to the delinquency of a minor, and she did skip her bail for Mexico.

But that’s the end of the story. We have the right woman. Mary Maud Wright (nee Dunn), aka as Lilith Lorraine, was going by the name Gertrude in the 1920s. And she had an interesting career during that decade. Let’s set aside the detective stuff and get back to the story. It’s a good one.

Lilith and Cleveland had found Theosophy. Catholicism, Baptism, even Methodism, these were fine with the Dunns, but Theosophy went too far. “The poor old dears wouldn't understand,” she was quoted as saying in the Oakland Tribune, 12 March 1927. “You know, they never did.” That may be the reason why they moved to San Antonio—where they were reportedly involved the Theosophical community—and then West: San Francisco had always been open to transcendental and alternative religions, while Los Angeles and Southern California was poised on the brink of doing so. They may have also spent time—according to an Oakland Tribune article dated 13 March 1927—in San Luis Obispo, at the Temple of the World at Halcyon. In 1924, Lilith conceived the idea of a series of “Sacred Schools” dedicated to the teachings of the Great White Brotherhood—the ascended masters of Theosophy. Around this time, she was holding seances at her home on 2325 Dana Street in Berkeley (not far from where the Fortean Anthony Boucher would live later). She was also studying Oriental occultism—which may explain her later claim that she studied at the University of California.

Always industrious, Lilith expanded the schools rapidly, at least by her own account. There were branches in San Francisco, San Jose, Reno, Portland, Chicago, San Antonio, Corpus Christi,and Mexico City. She claimed to have a mailing list 1,0000 names long, and a number of prominent citizens belonged—among them the lawyer who would defend her in court (once a journalist and city councilman), Russell Alley, who worked for radio in Los Angeles, and a San Francisco dentist. In 1925, she and other members staged a play—“The Return of King Tut"--to raise money for building the schools. At the time, lessons were being taught at her home (468 Forrest Street, Oakland) and a building in San Francisco, on 1975 Clay Street.

The school taught what sounds like--reading between the lines the newspaper accounts--rather standard mix of Theosophy and New Thought—character building and the removal of hate from one’s self; laws of mind, including thought transference; will; abstract philosophy. The point was to bring about a revolution that birthed Utopia and what their literature referred to as a Superman—meaning, it seems, someone in the mold of Christ, who was seen as the Perfect Man. According to Cleveland, they taught the wisdom of a mystery cult that had existed in Egypt and had instructed Christ. Lilith played the part of the high priestess, Zereda. (Alley seems to have been her second in command, and went by the name Omar.) Students seem to have been attracted to the so-called cult to develop themselves, discover wisdom, and aid in their evolution—all to help mankind.

Existence of the cult came to public knowledge in late winter 1927. Neighbors apparently had been complaining about the rituals, but to no effect. And then the mother of Thelma Reid—who had been introduced to the school by her mother—found what she considered obscene poetry. She bought these to the attention of authorities, but again there was no action. Finally, Margaret Merwin, mother of Caroline, an 18 year-old member, also went to the police. Earl Warren—then District Attorney for Alameda County, later Governor and Supreme Court Justice—looked into the case and decided a raid was warranted.

As I gaze out through prison bars

Life is not half so gray,

As souls of men whose bars of hate

Shuts God’s pure love away.

Better the stars through prison bars,

With only a gleam to guide,

Than the stinging goad of an open road,With conscience at our side.

School members chalked up the commotion to a disgruntled member—but officials and journalists had a more lascivious story: the state—indeed, the world--was being overrun by free-sex cults and immorality. Look at Aleister Crowley and the OTO, they said. Look at what was happening in a quiet Oakland neighborhood. The Tribune printed excerpts from the School’s publications and some of the poems--presumably written by Lilith. Warren said “obscenity” was the cult’s chief ritual. because some of the material was transmitted through the mails, federal officials looked into the matter, too. One called it, a "pernicious, revolting, nefarious and immoral” love cult.

One trial did emerge out of the fracas. Russell Alley was charged with the delinquency of a minor. Caroline Merwin testified that she and Lloyd Alley had improper relations at his father’s house; Lloyd denied that, and denied a confession he had made earlier, saying he had admitted guilt just to end an argument. The guy debated ten minutes, and convicted Russell Alley. He served six months in jail (two years was the maximum.) The judge said he had taken into consideration that Russell permitted—but did not force—Lloyd to take part in the ritual. Meanwhile, after giving a lecture on their ideas in San Francisco, Lilith and Gibbs skipped out on their bonds. They were eventually found in Mexico, but neither Warren nor federal officials cared to demand their return since they had been disappointed in Alley’s light sentence. The 1930 census has Russell back in LA, with his wife and son, working as a radio engineer. I believe that Gibbs—who had for a time been living at Lilith’s home—reconciled with her husband and children, and they returned to their home state of Missouri, she going by the name Zelma.

The next decade or so of Lorraine’s life is even more mysterious, because I can find no contemporary accounts of what she did. According to her later recollections, she spent seven years in Mexico, three of them studying in Mexico City, four in Saltillo, where she established the "Emilio Carranza Academy of Commerce and Languages.” She also claims to have graduated from the University of Arizona during this time—or at least took classes, the reports are contradictory. Her schooling, she said, was paid for by science fiction stories she sold to the pulps. Unfortunately, I can find no evidence from the time that she studied at the University of Arizona or had anything to do with the founding of the Mexican school—indeed, I can find no evidence that the school existed at all, having searched for it under English and Spanish names. There are many mentions of Emilio Carranza in Saltillo—he was a famous Mexican aviator from that town—but no school in his name. Lorraine did indeed publish science fiction at this time, adopting the Lilith Lorraine pseudonym for unclear reasons, but the known production would not have been enough to support her purported academic studies. That’s not (necessarily) to say these claims are untrue—just unsubstantiated—and a convenient way of erasing the more unseemly parts of her past. Given, though, that the conventional sources have her establishing that school in 1928, less than a year after her California humiliation, either the school was never founded, or was not very large or long-lived.

What can we say about her based on contemporaneous evidence? She’s in the 1930 census—only three years after she absconded from California to Mexico, giving her just enough time to have studied in Mexico City, if that indeed happened. According to that document, she and Cleveland were back in the Corpus Christi area. He was again working as a streetcar conductor; she had no job listed. Their finances seem relatively tight: they were renting a home for $25 dollars and did not own a radio. In1932, she edited her father’s memoirs, and included a poem she wrote herself—as Lilith Lorraine. It was published in Dallas. She also appeared in The Corpus Christi Times, dated 18 August 1933, without mention of a Mexico adventure—but the description of her activities do seem to build on what she had been doing in California, in a (purposefully?) vague way:

“Writer and Analyst to Lecture Saturday

Lilith Lorraine, Corpus Christi writer and vocational analyst will give a lecture Saturday night at 9 o’clock in room 258 at the Nieces hotel on ‘The Laws of Personal Magnetism.’

For the past three weeks Miss Lorraine has been presenting her analyses under the auspices of the Nieces hotel for the benefit of its guests and is now bringing her regular lecture series for the general public.

Miss Lorraine is a graduate of the University of Arizona and has spent a number of years in lecture work of a psychological and scientific nature.”

The theme of ‘personal magnetism’ especially resonates with her having led a spiritual group, and her time in Oakland could also be reflected in the claim that she had spent years of lecturing. I do not know what to make of he being a graduate of the University of Arizona: there just does not seem to have been enough time for her to have spent years in Mexico, founded the college there, took classes in Mexico City and graduated from the University of Arizona, in addition to the part os her life she was excising.

The name she had adopted, its origins is also unclear. In a 1951 article for the Corpus Christi Times, she recalled, “I worked my way through college by writing science fiction.” And this experience taught her to use the pseudonym: “I sent three manuscripts to three different magazines,” she said. “Every one of them was rejected. At first I though none of them were good, but after a time I decided to try again.” All three, she said, were then accepted, and the publisher’s congratulated her on her unusual name. The timeline here is hard to square, since her first science fiction article came out in 1929, and it was under the pseudonym Lilith Lorraine. Two years before, she may have been taking a few classes at the University of California, but her energies seem to have been otherwise directed. And the year before she was supposedly establishing the College in Saltillo, Mexico. More likely, the name was a way of disassociating herself from her past, and honoring some of her influences: Lilith is Adam’s mythical first wife, a subject of poets such as George Sterling, who she may have known in the Bay Area, and certainly read, as well as a symbol of the powerful feminine force, which showed up in her Theosophical philosophy, poems, and science fiction.

Altogether, Lorraine is known to have published five science fiction stories between 1929 and 1935. She may also have written mainstream short story in 1935 under the name Mary Maud Wright, “Books Hold That Line” for The Household Magazine. Not a very substantial output. The stories continue the Theosophical theorizing that seemed to be at the heart of her Sacred School. The first story, “The Brain of the Planet,” was published in a Hugo Gernsback dime novel (Science Fiction Series 5). Set in 1935. It featured a socialist professor at the University of Arizona, who proves the existence of telepathy, with a mechanic, builds in the mountains of Mexico a giant telepathic radio that converts that world to a socialist Utopia. The professor himself—like Lilith Lorraine when she was Gertrude Wright in Oakland—plays the part of Christ, assuming the responsibility for changing the world, knowing it cuts against human individuality and freedom, but that it is for the common good. Biographers have speculated that she may have chosen the setting—the University of Arizona and Mexico—based on her experiences there, but it seems just as likely that she transmuted that fiction into her own fact, making herself a graduate of the university and a radio operator—her Mexican academy was supposedly associated with radio station KGFI in Corpus Christi.

That is not to say there were no biographical connections in her fiction. The theme of a worldwide revolution and the coming of a Utopia brought about by a Christlike figure certainly reflected Lorraine’s teachings in Oakland. And her second story, 1930’s Into the 28th Century, was set in Corpus Christi. This story, too, was published in a Gernsback serial (and came with a drawing of the author that can now be found widely on-line), Science Wonder Quarterly January 1930. Likely, though, it was Gernsback’s second-in-command, David Landes, who was handling the day-to-day operations of the magazine and wrote the introduction to the story. (It may be, too, that the switch from Gernsback to Landes accounts for the differing experiences Lorraine had from science fiction editors, if that story is indeed true.) The second story also has a Theosophical ring to it, told from the perspective of a Corpus Christi man who travels 800 years into the future—where after several stages, true socialism has triumphed, women and men are equals, drawn together by bonds higher than sex and lust, and other biological necessities (childbirth and eating) have been simplified by technology—is presented to the world by his aunt, a writer who is living somewhere in the Orient—an alternate Madame Blavatsky, then, presenting an alternate racial history of the world, that ends up with a Utopia. There are, to be fair, other influences too, among them Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland.

Another 1930 story by Lorraine, “The Jovian Jest,” may have been her best known; originally published in Astounding Stories, it was reprinted several times. The story had a Lovecraftian edge, with a ‘nameless thing’ being found in a farm patch, attracting scientists and journalists to watch it grow and here its message—a cosmic one, as in Lovecraft, but with an anthropocentric core that is very un-Lovecraftian. The bulk of the story is a lecture given by this nameless thing, after it captures the mind of a visiting Professor, describing the way its race lives in harmony with the cosmos, knowing truth innately, without recourse to the five senses, and experiencing a transcendence beyond words (not incidentally, themes that would recur in Lorraine’s later poetry). Humans, the thing reported, might someday reach such a state—but currently was not equipped to learn anymore, and so could do nothing but forge on in hopes of obtaining that nirvana. The whole thing might have been a mass delusion, the unnamed narrator said, except for one thing: the revived Professor had the brain of a farmer that the creature had earlier tried to use as a vessel, while the farmer now spoke like a Professor. Thus—a jest, even a Fortean wink, and one wonders if Lorraine had already come across Fort’s two books.

She published another pair of science fiction stories in 1935, “The Celestial Visitor,” which appeared in another Gernsback property, Wonder Stories (the renamed Science Wonders Quarterly), and “The Isle of Madness,” in the same magazine, different month. I have not seen either, but they are both reviewed in (Fortean) Everett F. Bleiler’s Science Fiction: The Gernsback Years. He calls the first “A very bad job that would be considered a weak parody were the author not so obviously serious.” It concerns, again, Theosophic themes and Utopian civilizations: in this case, while Atlantis was dying, some citizens escaped to another planet and established a perfect civilization. One day, far in the future, a bored member of this race, discovers its terrestrial origins and journeys back to earth, where he is jailed (shades of Lorraine’s Bay Area experiences), heralded by a journalist, and falls in love with a judge’s daughter, the two returning to the visitor’s home as “eternal mates.”

Bleiler also finds “little to recommend” in the final story, “The Isle of Madness.” It concerns America in 1940, a country that has turned fascistic, devoted to a religion that combines materialism and violence, overseen by a mechanical mind. Those who resist the conformity and display their individuality are exiled to a Polynesian Island, given the ironic name the “Isle of Madness.” There, over civilizations, they develop super sciences and come into telepathic contact with some kind of divinity or human master soul. In time, the soul tells them to spread out across the world, where they see humankind has collapsed into wolf-like creatures and civilization is no more. Another Theosophical fairy tale, then.

As it happens, 1935 is also the year in which Lorraine’s name appears in the newspapers again, at least as far as I have been able to find. She is still known as Lilith Lorraine, with no mention of her other identities. In all cases, she is noted for her poetry: a story in Pennsylvania’s Reading Times (18 September) mentions her contribution “Those Who Dream of Wings” to the sixth issue of The Galleon. And at least three newspapers reprinted a poem of hers from Poetry World called “The Living Dead” from May to July 1935. She next appeared in 1937 newspapers, noted for being included in a book of Texas poets, for publishing her own book of verse, Banners of Victory (put out by Emory University’s Banner Press), and for lecturing the League Against War and Fascism. The title of her talk was “The Writers Organize Against War,” which reflects her continued Pacifism but doesn’t seem to have the Theosophical motifs of her other publications. These articles all have her in Texas, deepening the mystery of when—if ever—she was spending extensive time in Mexico and Arizona.

Steve Sneyd found some evidence suggesting that she may have been planning her own science fiction magazine (maybe even moving to England to do so) but events conspired to expel her from the genre for a time and find success in a different, though related, field. Domestic duties overwhelmed her in the mid-1930s when an uncle died and she was forced to attend to his large estate. She did continue writing science fiction, but could not get published. Perhaps her Theosophical musings were becoming cliched in science fiction proper. She said, “I turned to poetry after my series of science fiction rejections, and have appeared in early all the verse magazines, a large number of paying publications and the The Literary Digest.” Supposedly, she squirreled away some 25 science fiction stories that could never find a home. She published only once more in science fiction magazines before World War II, and that was a poem “Earthlight on the Moon,” in Stirring Science Stories, edited by Donald Wolheim. Increasingly through the 1940s, her poetry became decoupled from science fiction and focused on more mainstream themes.

From her earliest work, Lorraine showed an interest in the language of science, especially atoms. Banners of Victory, though, did not have much science fiction in it—and what was their tended toward the strictly fantastic. There were Lovecraftian touches and a poem called “She” which was an homage to Rider Haggard’s novel of the same name. One can see a lot of Poe, a lot of Machen—Pan appears repeatedly—and even a Fortean note a poem called “Perhaps” reads "They say that who wars with the gods must lose,/In life, in death, and after--/Perhaps--but ask when your arms you choose,/Are the gods immune to laughter?” Showing connections with her earlier works, she uses the adjective Jovian a lot, speaks in an oracular voice, and announces the coming of new races, especially matriarchies, that have conquered the twin problems of greed and war. Romantic optimism is the constant tenor: "So I've cast my lot with the galaxies where the pathless comets race,/Brushing aside the simpering suns that keep to an ordered pace,/Flinging my Jovian laughter down, through the echoing aisles of space.”

In 1940, she reconciled her Theosophical past with her poetic present, founding what she called “The Avalon Poetry Shrine”—that last word a definite nod to the mystical forces she saw working in the universe and poetry’s relationship to it. At the time, Lorraine and Cleveland were living near San Antonio, and it was around this time she was said to have been a reporter for San Antonio newspapers—although again there is no evidence—either the San Antonio Express or San Antonio Evening News, reports differing. It is also around the time that newspaper articles started referring to her parenthetically as Mrs. Mary Wright, a seeming softening of the identity that she had adopted during the 1930s. In his memoirs, Cleveland Wright noted that Lorraine felt poets were necessary to culture: they held memories and created visions of the future. They touched on the negative, but did not dwell on it, choosing, instead, to inspire. This sense of poet as religious prophet came through in a mid-1950s publication by her, in which she wrote that Avalon was “Dedicated to the finding and training of new writers, who while not discarding the enduring values, courageously interpret them in the language of a changing world, Dedicated to the discovery and encouragement of genius in all forms that its gifts may not be lost to humanity or perverted by deprivation and misunderstanding. Dedicated to the restoration of wonder, surprise and spiritual adventure to life and literature and to the opening of new frontiers of mind that will give to peace its ‘victories more sublime than war.’ Dedicated to the development of a unified world culture, to the discouragement of bewilderment, incoherence, cynicism and defeatism in all the arts, and to the fearless analysis of those forms of mass deception that menace the peace of the world through the distortion of truth. Dedicated to the sincere belief inspired by the total failure of the so-called practical values to meet either the material or spiritual demands of our era, that the Golden Rule is the only successful law of life, and that ‘without vision the people perish.’”

At some point, the Wrights settled into the Episcopalian Church, a compromise of their various faiths, mostly because, Cleveland said, the Episcopalians did not preach members of other faiths went to Hell. Despite this concession to conformity, the two continued to hold mystical Christian views: That God was the same in all religions, that Christ had established ethical rules, and that a force of mercy and love structured the universe. There was still the Utopianism there, and the Romantic optimism, but the future depended less upon technological developments and socialistic revolutions, and more upon the religious awakening of the world. Poets, especially, whether Episcopalian or not, were in a position to nudge the world along—or be there to mourn when people made the wrong choices and the world went down in flames.

Starting in the 1940s and continuing through the 1950s, the Wrights moved often—though poetry was always Lorraine’s core, now, important to her new self-identity. They spent substantial time in New York, and also other parts of the South and the Midwest, even Mexico, where she started a national poetry day; as far west as Utah, but never California, though, tellingly. In 1946, she moved Avalon to Rogers, Arkansas, which became the center of her activities, although she and Cleveland did continue moving. She started publishing a great deal under the aegis of Avalon. Books included the poetry collection Beyond Bewilderment, who further moved from science fiction and may be the most bitter of her books; Lilith Tells All a 1942 textbook of poetry; They, a narrative poem that obsessed over the end of the world foreshadowed in World War II; The Day Before Judgment, another collection of poetry that came out in 1944; Let The Dreamers Wake, another poetry textbook; Character Against Chaos, a 1947 psychology manual for poets; and Let The Patterns Break, which reprinted her previous collections in addition to her childhood verse. She edited the anthologies Wings Over Chaos, Voices from Avalon, and Conquerors of Tomorrow. She started the journal Raven in 1943, which was soon absorbed by Different, the ‘zine that represented her rapprochement with science fiction. All of this was done by 1947.

If Cleveland Wright’s account in his memoirs is to be believed, then Lorraine was whatever the poetry equivalent of a hack is—and I mean hack in the most complimentary sense. She knew her markets, knew what she wanted to say, and wrote it up quickly and directly—the best of the pulp tradition. She did not dither, was not paralyze by the plight of the artist in America or the state of the culture; it’s the difference between someone like Lovecraft, who played the part of the tortured artist, and, say, Isaac Asimov, who churned out serviceable prose day after day. She completed her domestic chores in the morning, then sat down to write, often finishing requested poems the very same day she received he request. She answered her own mail and performed a long list of free services for poets, including editing, critiquing, and helping negotiate with other poetry magazines.

Around late 1946 or early 1947, Lorraine changed the name of her foundation to the Avalon World Arts Academy, which seems to reflect her engagement with wider cultural issues. She had never been a fan of modern poetry, writing, "To parade his frustrations, to acknowledge his defeat, to unveil his psychopathic case history to a generation already in the grip of a planetary neurosis, to indulge in weird distortions of the patterns of a poetry, merely for the sake of being different and not for any sane or logical reason, to attempt to disguise his emotional infancy, his intellectual anemia, and his spiritual poverty under the guise of linguistic gymnastics; deceives no one." She wanted, instead, inspiration: "In my appeal to this vast audience, I have declined to be impressed by the anti-poets whom the people have repudiated. It is not the chopped prose, the buzz-saw rhythms, and the intellectual vaporings of these hostlers of the stable of Pegasus that the soldier carries into battle, that the preacher thunders from the pulpit, that the child learns from his text-book, that the pilgrim hurls as a shining weapon at the fearful shapes that close around him in the Valley of the Shadows.” And it was at this time that she became an activist along these lines—an activism that would intertwine with her return to science fiction and her connection with the Fortean Society.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, there was a battle among poets over the meaning of Modernist poetry and its place in the canon. The battle was a complex one, involving overlapping alliances between poets who were, to a varying extent, opposed to the entire modernist movement and those who saw modernism associated with communism and so stood opposed to it on political grounds. Against them were arrayed a network of poets who continued to write poetry that was both Modernist and socialistic, those who were socialistic, and those who were opposed to communism but still appreciated the modernist movement. (This last group was overrepresented in San Francisco, where the various renaissances surrounding the likes of Robert Duncan and Kenneth Rexroth kept alive the experimental edge of Modernist poetry.) As a number of Forteans and Fortean associates were poets, the battle involved them, too—Rexroth, for example, and Pound, who was an especially difficult case, since he was a modernist poet but also belonged to the right wing: his being locked up as insane, though, nicely made the case that his verse was also insane. The Humanist, a secular magazine that had some ties to the Fortean Society, hired an anti-modernist as its poetry reviewer. Peter Vierick, son of George Sylvester Vierick, Nazi sympathizers and Fortean-connected, was among those leading the charge against Modern poetry—a charge that was successful and, by 1957, had de-radicalized modern poetry, separating it from socialism and communism, appreciating that it had done away with the slick rhythms of Victorian prosody, but also not wanting further experiments.

Lorraine was among those who worked against modern poetry, with another science fiction writer and poet, Stanton Coblentz. (His early work had also ben Theosophically inflected, with stories in the 1920s about Atlantis.) Around 1946, he started the League for Sanity in Poetry—which was a general statement about the craziness of American poetry, but also a stab at Pound, who had just been admitted to St. Elizabeth’s Hospital, on the psychiatric ward, where he would stay for a dozen years. Coblentz and Lorraine became close collaborators—she was on the board of the League, and for a time it was headquartered at her house. Avalon was re-designed to serve the goals of the anti-modernist crusade: modernists used obscurity to discredit all of poetry, and so in response Avalon advocated clarity and eternal values as the bulwark of democracy. That was the point of her book Character against Chaos. Her magazine Different also served the purpose of this fight, even as she re-engaged with the science fiction community.

Different was explicitly political, Fortean, and science fictional. It provided “safe havens for anti-modernist members of the League for Sanity in Poetry” and offered articles sussing out the hidden communism in modern poems. (A companion to a feature in Coblentz’s own magazine Wings, called “This Is Not Poetry,” which showcased examples of Modern poetry.) For all her Theosophical leanings, Lorraine had always had a conservative aesthetic, equating truth and beauty in her earliest poems, so this political turn was not a stretch—like the Fortean George Bump, Lorraine found her individualism leading her to more conservative patches of the political spectrum as she got older. The magazine also had a department of Forteana called “Strange Experiences,” which was edited by Dariell Dungy. Send believes that this is likely one of Lorraine’s pseudonyms. Unfortunately, I cannot comment on this part of the magazine because I have not actually seen any issues of Different: they are very rare, and very expensive.

Lorraine used Different to reach out to the science fiction community. Notices of the magazine were made in Walter Gillings’s “Fantasy Review” as well as Walter Dunkelberger’s “FANEWS.” Eric Frank Russell kept a file on her. A 1948 issue of “Fantasy Review” announced some of Lorraine’s plans:

“Different, journal of the Avalon World Arts Academy, Rogers, Arkansas, whose founder-director is Lilith Lorraine, one-time contributor to American science-fantasy magazines, will devote its Sept.-Oct ’48 issue to ‘The Conquest of Space.’ Poets and writers throughout the world are invited ‘to divert the minds of our readers from the minor dissensions that lead to war on this little planet by submitting poems and stories’ on this theme.

Cash prizes are offered for the twenty best poems selected by reader-reaction and received before July 1st. No poem must exceed twenty lines; entries will be judged on thought-content and style. By space conquest is meant, not the subduing of possible inhabitants of other worlds, but the ‘bringing of the blessings of true civilisation where they are needed, and the willingness to learn from higher civilisation if such be discovered.’

Science fiction authors in particular are invited to submit stories on the theme for publication in this and a later issue of the magazine. Ten dollars will be paid for each one accepted and marketing advice given in respect of entries which are not suitable or cannot be accommodated. Word-limit is 2,500; hackneyed plots are not wanted and the best literary style desirable. Final judge in this department will be Stanton A. Coblentz, fantasy editor of Different.

The ‘Ask Me Anything’ department of the magazine will also be devoted to the subject, prizes being awarded for accepted questions dealing with aspects of space conquest which are not merely mechanical.”

The resulting issue, in Gillings’s phrasing “rhapsodised over ‘The Conquest of Space,’ with guest editorial (‘Stairway to the Stars’) by U.S. Rocket Society’s R.L. Farnsworth,” who was also a Fortean. The issue further announced that the magazine would like to publish even more science fiction.

In the meantime, Lorraine herself had returned to the pulps, now as a poet. She published at least ten poems in professional or amateur magazines over the next dozen or so years. And her poetry collections showed a renewed interest in the genre, culminating in her 1952 collection Wine of Wonder, which was completely devoted to science fiction, and her later magazine, replacing Different, called Challenge, which was also primarily devoted to science fiction—“The Poetry of the Atomic Age” as she called it. Through the magazine, she hoped to invigorate science fiction, aesthetically and psychologically. She disliked the turn to Dianetics—preferring her own Character Over Chaos—and promoted new voices—she was the first to pay Robert Silverberg for a story. Lorraine sought to chase out what she saw as the vapid cliches of the genre (and, though this she did not say, replace them with her own, cosmic cliches). She lectured in one issue,“Love-themes, if used, must be subordinated to the scientific premise, and lovers must be presented as having evolved from the the sex-mad or self starved possessive, hard-boiled or slushy expendables of this day and age. Allowances must be made at every turn for the normal evolutionary processes which will eventually enthrone the reason, mature the emotions and refine the intellect. Do not, therefore, portray a future era as having the same fossilized institutions, and primitive prejudices, fears and bewilderments of our own age, unless you intend to satirize such atavisms by contrast and to liquidate them as a menace to civilization. Do not portray beings of the far future using current American slang or the twelve-year-old vocabulary of the 1950 college graduate. Don’t make earthlings the heroes of the future eras unless they have evolved a civilization which cultivates its full brain capacities, and make it possible for us to learn from civilizations older than our own. The more skillfully you can create new and higher forms of government, ethics, religion, and harmonious human relations, the better we shall like your story. We have no taboos on constructive dreaming.

But it is too broad a statement to call her writing “science fiction.” As Sneyd remarked, the distinctions in her writing between horror, fantasy, and science fiction were always hazy. If she is to be placed anywhere in the field, it is with those of a Theosophical bent, obviously, but also those who wrote cosmic horror, a la H.P. Lovecraft. She published Clark Ashton Smith in her own magazine and Smith, who wrote the introduction to Wine of Wonder, praised her as belonging to the tradition of weird writers dating back to Bierce, continuing through Sterling and Lovecraft and himself: “Lilith Lorraine, poet and seer, walks intrepidly the ways that science has opened into the manifold infinities. She widens the scope of wonder into stars and atoms, into ulterior worlds and posterior ages.”

And, indeed, this cosmic vision is one that recurs through her poetry, science fictional and not, rooted, no doubt, in her Theosophy, though transcending it. "Truth is what the gods make it--/And there are many gods;/ Beauty is above all gods,/ Immutable, immaculate,” she wrote, in what might serve as an epigraph for her. Transcendence was where the eternal feminine could be found, where Christ resided, and where Utopia beckoned. Not all of her poems shared this vision, but there is no doubt it is the dominant theme. It connected her religious views and her aesthetic ones, and stood outside the realm of politics (she thought—though it was inherently political). The poet, for her, was a prophet, speaking what was true, and could either be vindicated or avenged, as she put it, depending upon what choices the world made: to heed to voice or to find destruction. The apocalyptic edge of her poetry, always present, became especially sharp with the coming of atomic weapons (Different was subtitled “Voice of the Atomic Age”). As she had when she was arrested in California during the 1920s—as she expressed in her first science fiction story—as she did in the battles over modernist poetry—so she expressed in her own view of herself: she was a Christ-like figure, a potential martyr, outlining the ethical codes for the world, certain to die, but providing the earth with a great example.

Cleveland Wright had officially retired by the time he filled out his World War II draft card. Lilith Lorraine kept working for longer, but by the early 1960s, she too considered herself retired. Her last years were made harder by significant health issues, a heart attack in 1965 and then a series of strokes. Cleveland died in April of 1967, somewhere between 79 and 81 years old, depending upon which official documents one accepts as true. Lilith lasted only a few months longer, passing in November 1967. Her age, too, was somewhat mysterious, somewhere between 73 and 75 years old. They had no children, and Lorraine’s legacy would be obscured shortly after her death. She was never canonized with the other writers of cosmic poetry. And science fiction poetry of the 1970s was so influenced by the so-called New Wave that it had little time to look back on its own history, as Sneyd remarks. And so she was mostly forgotten, a Fortean who became herself something of a damned fact—and, indeed, remains one, with many mysteries, not perfectly amenable to analysis.

Exactly when and where and how Lorraine came across the writings of Charles Fort is also mysterious. As noted, there are elements of her earliest writing which have a Fortean flavor, suggesting that she may have started reading him as early as the 1930s. And her later poems, too, seem to have had a Fortish influence— “Time is a Circle” is the title of one, “Since We Are Property” another. Certainly, the communities with which she moved—Theosophical and science fictional—would have exposed her to Fort’s writings. She knew Clark Ashton Smith, who was influenced by Fort, and worked with the weird artist Ralph Rayburn Philips, who was a member of San Francisco’s Chapter Two of the Fortean Society. Another Fortean, the writer Miriam Allen DeFord (who had actually corresponded with Fort) was a member of Lorraine’s Avalon Foundation. No doubt there are many other connections. Heck, Stanton Coblentz probably knew of Fort, too.

She seems, though, to have used Fort—as many science fiction authors did—as a sourcebook for ideas; her poem “Fireflies,” for example has Fortean imagery: "The stars are trapped in a space-web/Swing from sun to sun/Where Time, like and Evil Spider,/Eats them one by one.” As well, Fort—or strange, anomalous experiences—proved that the universe was vaster than scientists could fathom. She wrote in one poem, "If you are brave enough to give the lie/To all the 'facts' and stand where prophets stood--/Then read this book, and raise your banner high/Above the barricades of brotherhood.” And this worshipping of science brought only pain in the material world. Fro,m her narrative poem “They”: "Poor man, who counted all save science loss;/Poor man who branded wizardry as dross;/Has lost the Speel that might have saved his world/From the Black Magic of the Twisted Cross.” As opposed to the narrowness of science—which Fort pointed out—there was her own system (not Fort’s), Theosophical, mystical, and conservative—Fort, then, as a sourcebook again, not for ideas, but to prove science limited.

At some point, Lorraine became a member of the Fortean Society, but it was a short-lived connection. Likely, her membership came with promotional efforts for Different, although Tiffany Thayer’s mention first mention of her, in Doubt 14 (Spring 1946), could be read as implying she had been a member for some time before that. He mentioned she was a Texas writer and MFS and was putting out Different. One different thing was that almost anybody could understand the poetry, he said, but followed this with a jab: “Whether it is all worth printing or not is another question, and one which nobody asked us to answer.” Thayer further noted the existence of Dunay’s department of Forteana, “Strange Experiences.”

Lorraine warranted only one more mention in Doubt, and this one was Thayer’s kiss-off. It came in Doubt 27 (Winter 1949). “Never Kick a Lady,” Thayer titled the short article. “The lady we are not going to kick is Lilith Lorraine, a sometime pretending Fortean who promotes doggerel of the lowest order in her magazine, DIFFERENT, under the blanket justification that it is ‘sane.’ SANE, it may be, but poetry, it is not, and no publication has been so flagrantly misnamed as Different since a newspaper in Seattle was christened ‘The Intelligencer.’” He underlined his opinion in a letter to Eric Frank Russell at the same time: “Lillith gets a razberry from local members for her mag. Sometimes I think only thee and me is not nuts.”

Although Thayer’s comments are fairly cryptic, it is not hard from the story to see why she was ex-communicated (even as he was reluctant to call out the likes of Ben Hecht). As I say, I cannot speak to what may or may not have run in “Strange Experiences” that may (or may not) have irritated Thayer. And she was not the only Fortean to use Fort as a sourcebook, either for story ideas or to support some type of mysticism (often Theosophical). Thayer was not always pleased with such uses of Fort, but rarely was he so antagonistic to them—although, to be fair, Thayer could be often surly and turn even on friends. There may also be a gender issue here. Thayer fancied himself an expert on female psychology (really!) even as his fiction . . . uhh, belied, seem le mot juste . . . and that expertise seemed to be based on the notion that women were relatively small-minded and driven by trivial things: not the great principles that drove the best of men. It would be easy for him, then, to dismiss Lorraine’s stated preferences, or the rich history in which they were rooted.

The crux of the biscuit, though, would seem to be Lorraine’s anti-modernism, and especially The League of Sanity in Poetry’s hatred of Ezra Pound—Ezra Pound who was one of Thayer’s idols. Ezra Pound who Thayer was trying to free from the mental hospital. Ezra Pound for whom Thayer was offering to buy underwear. Ezra Pound who mentioned the Fortean Society in his Pisan Cantos—which won the Bollingen Prize in poetry to much gnashing of teeth can rending of breasts among the anti-modernists.

I cannot make the case as convincingly as I would like without access to Different. But it is worth not ing that the September-October 1949 issue (volume 5, no. 4) had a column by Coblentz called “The League for Sanity in Poetry,” which Thayer seems to be singling out—and which definitely derided modern poetry, if no Pound specifically. The following issue, November-December 1949, had another column on the League, this one by Nathaniel Starr, and in the following issue, January-February 1950, Coblentz returned with another plug for the League and hit on modern poetry. Depending upon when these came out, and what they said, likely these columns were the source of Thayer’s irritation.

Thayer never mentioned Lorraine again, and as far as I know Lorraine never mentioned the Society or even Fort. But the Fortean touches remained in her work. She was a Fortean in more than name.