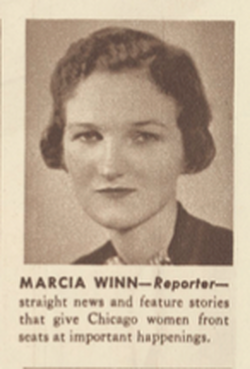

Winn as a college senior.

Winn as a college senior. A pair of unsentimental journalistic Forteans.

Katherine Marcia Winn was born 11 June 1911 in Danville, Illinois, making her only a few years younger than Tiffany Thayer, and native of the same state. Her parents were Emma Frances Coulter, and Walter Edward Winn—who could trace his ancestry in the U.S. back into the 17th century, with relatives who fought in the American Revolution. They were old-stock Anglo-Saxon who had fought for the Confederates in the War Between the States. Katherine was the fourth of six children. She spent most of her youth in Little Rock, Arkansas, where her father plied his trade as a civil engineer for the government. They owned their home in 1920, though with a mortgage. In 1930—Marcia aged 18—the census has the three youngest still at home, along with a maternal grandmother. Some names had changed a bit by this point. Emma Frances was going by Frances, probably because her mother was also named Emma. Katherine had dropped her first name and was going by Marcia.

After finishing high school, Marcia sent a year at Little Rock Junior College before moving to Mississippi State College for Women, in Columbus. She was on the newspaper—“The Spectator”—all three years there, including editing it as a senior. She was involved with the YWCA, the hiking club, dancing, the posture league, vesper choir, the theater, and student government. She graduated with a Bachelor’s of Art, and returned to Little Rock, where she worked for the Arkansas Gazette. Initially, she worked without pay, but eventually started collecting paychecks. In 1934, she moved to Chicago to work for the Tribune. She spent the rest of her abbreviated career there, married, and had children.

Katherine Marcia Winn was born 11 June 1911 in Danville, Illinois, making her only a few years younger than Tiffany Thayer, and native of the same state. Her parents were Emma Frances Coulter, and Walter Edward Winn—who could trace his ancestry in the U.S. back into the 17th century, with relatives who fought in the American Revolution. They were old-stock Anglo-Saxon who had fought for the Confederates in the War Between the States. Katherine was the fourth of six children. She spent most of her youth in Little Rock, Arkansas, where her father plied his trade as a civil engineer for the government. They owned their home in 1920, though with a mortgage. In 1930—Marcia aged 18—the census has the three youngest still at home, along with a maternal grandmother. Some names had changed a bit by this point. Emma Frances was going by Frances, probably because her mother was also named Emma. Katherine had dropped her first name and was going by Marcia.

After finishing high school, Marcia sent a year at Little Rock Junior College before moving to Mississippi State College for Women, in Columbus. She was on the newspaper—“The Spectator”—all three years there, including editing it as a senior. She was involved with the YWCA, the hiking club, dancing, the posture league, vesper choir, the theater, and student government. She graduated with a Bachelor’s of Art, and returned to Little Rock, where she worked for the Arkansas Gazette. Initially, she worked without pay, but eventually started collecting paychecks. In 1934, she moved to Chicago to work for the Tribune. She spent the rest of her abbreviated career there, married, and had children.

Winn, 1938.

Winn, 1938. The Tribune, at the time, represented what was then considered an Old Right position, under the editorship of Colonel Robert R. McCormick. It was staunchly opposed to Democrats, the New Deal, Europeans, immigrants, Communists (it was pro-McCarthy, pro-Chiang Kai-shek), and war: the paper was deeply isolationist. Still, over time, the paper attained something of a reputation for hiring women journalists, Winn one of several—by 1957, 60 of the 300 staffers were women, a low number, no doubt, but striking for the period. Winn made her way up the journalistic ladder, starting out with odd stories—she never really gave these up—on somewhat trivial subjects: amateur restaurant reviewers, the price of seats in the buildings around Wrigley Field. She met with a Fundamentalist group in the mountains of Tennessee and followed the path of a tornado by plane. She wrote about attempts to control STDs by requiring blood tests before marriage—and the people who evaded the tests. She covered the movement of women into the workforce during World War II. Her first story was supposedly an interview of a monkey that had escaped from exhibition. She continued to turn out copy, gaining a reputation as hard-working and unsentimental.

The 1940 census had her living alone, renting a place. She had suffered some—she lost a brother and a sister separately in the 1930s, and her father passed in 1941. She was not a hermit, though. There’s a story that in 1942, when he moved to Chicago for a time, she spent the night of a part necking with the composer John Cage. That year, she also took over a column “Front Views and Profiles.” Winn edited the daily-feature, and contributed regularly. I have read a bit of her output, but not made a full study of it. She clearly moved in artistic circles; in 1945, she wrote a long story for the paper’s Sunday magazine extolling the virtues of early American landscape painters. It was reprinted and sold by the Art Institute of Chicago. She had conservative inclinations, though, too, at least politically: “Taxes” magazine saw fit to republish one of her stories. In 1943, she was sent on assignment to Los Angeles, from which she wrote an exposé of Hollywood’s libertine ways, and also got a front seat view of the so-called Zoot Suit Riots. It’s clear that in the 1940s, though she was living alone, in a city distant from her family; though she had suffered personal loss; she had a rich life. Then, in 1945, she added to it, marrying George Edward Morgenstern.

Morgenstern lacked Winn’s deep American ties. He was born 26 May 1906 in Chicago to Jacob (aka John) Morgenstern and Nora Murphy. The elder Morgenstern had been born in Ohio to German immigrants; Nora had been born in Ireland. The two married in Chicago some dozen years before George entered the world. He was the second of two boys, nine years younger than William. Jacob made a living as a printer. The family lived in Oak Park, and the two brothers wen to high school there, where Bill went to work on the school newspaper and recruited his brother to do the same. They covered school sports. After graduation, George went to the University of Chicago, where he continued covering sports and working up to editor of the campus magazine “The Phoenix.” Journalism crowded out other aspects of Morgenstern’s life, so that he became a part time student, also writing (on sports) for the Herald-Examiner, as well as working as a rewrite editor there and reporter, covering some of Al Capone’s tax evasion trial. He did finally graduate, in 1930, with highest honors.

It’s not clear to me what Morgenstern was up to in the 1930s. Probably he was still attached ti the Herald-Examiner—though it’s not specified, it makes sense with the rest of his career. He also seems to have tried his hand at book writing. In the 1930s, there are copyrights to Morgenstern for books on “Abe Mitchell and the Rover Boys”—one subtitled “Abe Mitchell Goes to College,” the other “The Big Game.” These came out in 1934, the year Winn joined the Tribune. We knew they were the work of this particular George Morgenstern because the copyright address is Oak Park, Illinois. I have not seen these and am not even sure any copies exist: I can only find the copyright notice, nothing in library catalogs. (It’s worth noting “The Rover Boys” was the name of a series of books published from 1899 to 1926, thirty in all. Abe Mitchell is the name of a famous golfer. What the connections are here are impossible to know.)

In 1939—the year that the Herald-Examiner stopped publishing—Morgenstern moved to the Tribune as a reporter and rewriter. In 1941, he became an editorial writer. His journalism career was interrupted by two years of service during the War. In 1943 and 1944 he was with the Marines, discharged as a captain. (That’s what all the paperwork I have seen says; his headstone gives him the rank Lieutenant Colonel.) In addition to everything else, his military service would have been another connection with Winn: her father had served in World War I, and her brother was in the military. Morgenstern married Marcia Winn on Saturday, 15 September, 1945, in a small ceremony attended only by friends and presided by a Presbyterian Minister. Evidence of just how close the two journalists were to their newspaper and its publisher, the wedding was held at Colonel McCormick’s home, and he gave the bride away. The reception was held at the Southside apartment where the new couple would live. Winn opted to keep her maiden name for professional reasons.

With the marriage, Marcia’s career slowed down some. She gave birth two a daughter, Marcia, in 1946. At the end of 1948, she partially retired from newspaper work; in 1949, she gave birth to her second daughter, Nora. Meanwhile Morgenstern was making public waves. In 1947, he published a revisionist history of America’s entry into World War II, “Pearl Harbor: The Story of the Secret War.” It argued that Roosevelt was likely well aware of the coming attack, and wanted it as an excuse to get America involved in the conflict. The book won plaudits among other revisionist historians—such as Charles Beard and the former Fortean, Harry Elmer Barnes—as well as the socialist (and nominal Fortean) Norman Thomas. As far as I know, it was not taken up in the pages of Doubt, but retreads of the argument would help push another Fortean, the science fiction writer Robert Anson Heinlein, toward the political right.

Morgenstern’s work set the pattern of later World War II revisionists. An abbreviated essay digest appeared in Barnes’s edited volume “Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace” (which, intentionally or not, echoed Thayer’s Perpetual Peace Plan). He also wrote for the right-wing (and still barely isolationist) magazine “Human Events,” concluding, “An all-pervasive propaganda has established a myth of inevitability in American action: all wars were necessary, all wars were good. The burden of proof rests with those who contend that America is better off, that American security has been enhanced, and the prospects of world peace have been improved by American intervention in four wars in half a century. Intervention began with deceit by McKinley; it ends with deceit by Roosevelt and Truman.” By accounts, Morgenstern’s theories fit well with the tenor of McCormick’s editorial page, which was revisionist and remained isolationist. In time, Winn, too, came back into the journalistic fold at the newspaper, beginning a twice-weekly column on parenting (“You and Your Child”) in 1950 that was syndicated in some thirty papers. In 1954, she published “We Learn about Ourselves: Primer for Parents: a Guide to the First Six Years of Life,” through the “Encyclopedia Britannica.” She also returned to reporting.

In 1955, Colonel McCormick died; Morgenstern was given the job of writing his obituary, but could not do it—their friendship was too dear—and so Winn completed it for him. She also continued McCromick’s quixotic practice of spelling reform—a favorite of some Forteans, such as George Starr White. The newspaper never made their commitment explicit, or explained what it was doing, but rather simply used altho instead of altho, for example, or frate, frater, and sodder. The paper’s interest, though, seems to have declined after its peak in 1955. Winn went on to other matters. In 1957, she interviewed the thrill killer Nathan Leopold (of Leopold and Loeb fame) who seems to have come to terms with his act and took quiet pride in the prison work he did. The interview sparked widespread interest—it got Winn mentioned in “Time” magazine and won her journalistic awards, as well as prompting some calls for Leopold to be released.

It was around this time that Winn became ill. Her last few years saw her in poor health. She died 15 August 1961 in a Wake Forest Hospital. Her daughters were 12 and 15. She was only 50.

George soldiered on at the Tribune. In 1969 he became editor of the editorial page. In 1971, he retired, though he continued to contribute occasional editorials. In the early 1980s, it seems, he moved to Denver to be closer to his daughters and two grandchildren. He died 23 July 198. George Morgenstern was 82.

**********

It seems likely that of the couple Marcia Winn found the Fortean Society—before she found Fort—probably through an interview with Robert L. Farnsworth, the Fortean obsessed with colonizing the moon for America. Farnsworth started making Chicago newspapers in 1945, with his petition of the government to use atomic energy as a fuel for moon-bound rockets. During the post-Kenneth Arnold flying saucer flap, he was quoted in an article mentioning Fort as pioneering study of this phenomena in a Tribune story—likely done by Winn—that was picked up the U.P. and sent around the country.

It was this year—1947—that comprises the entirety of Winn’s contribution to Forteanism. She added a little to the Society’s publication directly, and did more by promoting it. Going beyond quoting Farnsworth, she seemed to find something of excellence in the Society and chose to advertise it. In March—before Arnold’s sightings, but after Farnsworth had been in the paper for a couple of years—Winn devoted one of her “Front Views & Profiles” columns to the Fortean Society, and its “Perpetual Peace Program,” which meshed well with the paper’s isolationist and anti-war stance. On the 29th, the paper published her piece:

P.P.P.

The Fortean society prides itself on being the only organization which has as its sole aim perpetuation of dissent from dogma. The title of its magazine gives a clew [Ed. Note: the spelling was not unusual at the time, but a hint at the spelling reform] to its theories, for it is called Doubt. The D is cut out of what seems to be the Einstein theory, the O is cut out of that celebrated picture of the Big Three at the Yalta conference, the U and the B are beyond us, and the T is cut out of the stock market reports. The society even doubts the Gregorian calendar, which the rest of the world uses, and dates its calendar from what we know as 1931 A.D.. To them that year is 1 FS [Fortean Society][Sic: its Fortean Style], the year of its founding. It also uses 13 months.

Enough of its background. What we want to pass on is its Perpetual Peace Plan, referred to by Forteans as P.P.P., which is based the premise that to maintain peace under the profits system is very simple. Just go to work for spending war-like sms of taxes and collecting warlike sums for charity. Give it all the aura of immediate necessity. P.P.P. so far has 12 planks:

A cyclotron in every high school.

An atom busting plant in every middlesex [some of the Forteans are English] and village.

Every waitress a Ph.D.

Every laundress a B.A.

A standing army of 10 million translators to translate every book ever written into every other language.

Subsidies for publishers to issue these books and for booksellers to see them on every corner.

A 200 inch Palomar White-elephant telescope at every crossroads.

Completion of the sculptured heads which Gutzon Borglum began to blast out of Mount Rushmore in the Black Hill and the extension of similar art to every bald knob in the world’s mountain chains. [Thereby using up all the explosives.]

Extend the experiments of J.B. Rhine with cards and dice, setting up Extra-sensory Perception laboratories at every public gathering.

Supplant all lie detectors in police stations and courts of law with motion picture cameras, lighting equipment, and sound recording devices tomato permanent, audible, visual records in close-up of all principals and witnesses in every trial. [Would spend untold piles of money and end sleeping judges and/or juries.]

Institute in all grammar schools, as an aid in vocational guidance, the Sheldon system for classifying physique and temperament. [This requires three still photographs of every child, one before, one behind, one profile, all nude.]

Finance R.L. Farnsworth, the rocket man, in a race with therapy to the moon.

If, however, the tax eaters demand ‘just one more’ war, the society suggests an improved war: Instead of sending Russian boys to the United States to wreck the place, and sending our mean to Russia to do the same, let each stay home and do its damage. The net result, the society asserts, is the same: Rubble and a rebuilding boom. The only argument that can be raised against it is its economy.”

A few months later, on 11 July 1947, the paper ran another of Winn’s “Front Views & Profiles” columns devoted to the Society:

“Pie in the Sky?

One colleague says those soft drink people are trying to make use concentrate on the night skies. [Ed. Note: Bay Area Fortean made the same suggestion around the same time.] Another, a loyal son of Nebraska, says the university there holds the world’s discus championship and is indulging in secret practice. As a Fortean [‘The sound Fortean holds all estimations of value in perpetual suspense’] who has so far seen nothing in the night sky more alarming than the moon, we can only refer you to the works of the late Charles Fort and say that there have been disks before this.

Science could never explain the phenomena Mr. Fort chronicled. That is why he wrote them. It wasn’t that he didn't believe beyond and around it. His role was to dissent from dogma. No, try again. Science often did explain the phenomena. It explained them _away_. Mr. Fort contended you couldn’t do that. They existed; ergo, they could not be ignored.

We don’t have the space to tell you of Charles Fort and the myriads of unexplained phenomena he recorded—rains of frogs, fish, rocks, snakes, black rains, red rains, yellow rains. Science laughed them all off. This si dedication to disk week, science is laughing again, and Fort, if alive, would laugh at science. Read his “Bok of the Damned” and you can laugh with him, but not at disks.

Fort records many disks or similar luminous bodies seen in night skies. Interested in a few of them? April 27, 1863, over Kattenau, Germany, great numbers of small shining bodies passing east to west. July, 1898, one, over Canada. Oct. 27, 1898, one, golden yellow and the shape of a three-quarter moon, over County Wicklow, Ireland, 16, 1818, a great group of them, the size of a hat crown and linked together in groups of eight, passing for two hours over Skeninge, Sweden. Late summer of 1877, many, which ‘looked like electric lights, disappearing, reappearing dimly then shining as bright as ever’ and moving at high velocity, over the west coast of Wales. March 23, 1877, described as balls of fire of dazzling brightness, over Vence, France, July 30, 1880, a large spherical light and two smaller ones, moving along a ravine, near St. Petersburg, Feb. 9, 1913, round luminous bodies moving singly or by fours with ‘a peculiar majestic deliberation,’ seen in Canada, the United States, Bermuda, and at sea. Feb. 24, 1893, globular bodies strung out in an irregular line, bearing northward, seen by H.M.S. Caroline between Shanghai and Japan. Late 1860’s [sic], the ‘false lights of Durham’ against the sky not far above land upon the coast of Durham. [Mistaken for beacons, they caused many wrecks and such excitement in England ha an investigation was held in 1866. The investigators reached the conclusions that the lights were ‘mysterious.’]

Many more could be cited, even one over Niagara Falls on Nov. 13, 1833, but the only conclusion a good Fortean can draw from the lot is that if the Russians are behind them, they’ve been at it a long time.”

*********

Winn’s second article came at a high-point of media interest in Fort and flying saucers; indeed, she may have been helped pique that interest. On 7 July, an unnamed Associated Press reporter in Chicago—quite likely her, or an acquaintance, if not someone Farnsworth knew—sent over the wires a report about Fort’s first book, and its chronicling of strange things in the sky. (Thayer would mock the report for calling Fort’s book “rare.”) The story appeared in slightly different versions, across the country:

“Current reports of flying discs had similar counterparts in the past, according to a rare book in Chicago’s Newberry Library.

In the “Book of the Damned,” a collection of ‘data that science has excluded,’ the late Charles Fort published a purported account by M. Acharius, of a visitation on a town near Skeninge, Sweden, on the afternoon of May 16, 1808.

“‘The sun turned brick red,’ Fort wrote, ‘at the same time there appeared on the western horizon a number of round objects, dark brown in color and seemingly the size of a hat crown. They passed overhead and disappeared on the eastern horizon.’

“Fort noted also the reported appearance over County Wicklow, Eire, Oct. 27, 1808, about six o’clock in the evening ‘an object that looked like the moon in its three-quarter aspect’ which ‘moved slowly, and in about five minutes, disappeared behind a mountain.’

“Other strange reports included those of ‘a luminous cloud moving at high velocity’ over Florence, Italy, Dec. 9, 1731: ‘globes of light seen in the air’ at Swabia, May 22, 1732, and even an ‘octagonal star’ sighted from Slavange, Norway, April, 15, 1732.

[Other editions included the following paragraph: “On March 6, 1912, an observer at Warmley, England, saw something in the evening sky, Fort trailed, that looked like ‘a splendidly illuminated airplane traveling at a tremendous rate.’”]

The similarities to Winn’s column are obvious, but the direction of the influence cannot be determined, not even be chronology. The issue becomes further muddied given that a raft of other stories soon followed, one by R. Dewitt Miller which did not explicitly mention Fort—he was promoting his book “Forgotten Mysteries,” so the earlier anomalies were “forgotten,” not “damned”—but fed into the sense that there was a deeper history to the current flap:

There have been thousands of reliable reports during the last 150 years of strange things seen in the sky. There are at least 100 cases in which the queer objects were said to have a ‘disc-like’ form.

Never have reports of strange sky phenomena been so widespread and so uniform as the ‘flying saucers.’

On March 22, 1870, a flat, light-colored disc was observed by the ship “lady of the Lake”, then in the mid-Atlantic between South America and Africa. The disc appeared to be of large size, and seemed intelligently controlled. A report of it was made in the Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society and a sketch included The sketch is strikingly similar to sketches made by observers of the flying saucers.

Other discs were seen in North Wales Aug. 26, 1894, in India in 1839, and in Norway Nov. 3, 1886.

It seems to me the three most likely explanations—and at this point only guesses—are:

The Army and Navy are experimenting wit a new weapon. Although they have denied it, there is much in favor of this explanation.

The discs actually are from Mars or somewhere outside the earth. The fact that similar objects were seen before the invention of aircraft strengthens this explanation. There has been increasing evidence of life on some other planets. If they are Martians, I would like to meet one.

They are things out of other dimensions of time and space. Certain thinkers in abstract science have long held that some other dimensional being conceivably could enter our world

Although many reports of the saucers are undoubtedly untrue or distorted, there is plenty of evidence that something very queer is going on.

Another Chicago reporter, Claire Cox from the United Press, made the connection between Fort and flying saucers via an interview with Farnsworth—there was clearly a competition between the two wire-services:

R. L. Farnsworth said today the ‘flying saucers’ reportedly racing through U.S. skies aren’t anything to get up in the air about.

‘People have been seeing things in the sky for years,” he said.

Farnsworth said he could speak as somewhat of an authority on the spots people are seeing before their eyes in skies from coast to coast.

He’s a member of the Fortean Society, a club for experts on the unusual things—on land and in the air—people have seen and thought they have sen through the centuries. The club was found in honor of Charles Fort, a diligent man who devoted his life to collecting four volumes of odd happenings.

“This isn’t the first time people have seen legitimate spots in the sky,’ Farnsworth said. ‘It happened at at least three times in the last century and plenty of other times, too. Nobody ever found out what any of the objects were.”

He said the Rev. W. Read, an amateur astronomer, and [sic: saw] a ‘host of self-luminous bodies’ pass through the field of his telescope in England at 9:30 a.m. Sept 4, 1851.

Read created quite a stir with his report on the 1851 version of today’s saucers in the monthly notice of the Royal Astronomical Society of Great Britain. He claimed he saw bodies moving both fast and slow in every direction for six hours.

Then in 1863, Farnsworth said, Henry Waldner, a Swiss, informed an astronomer at an observatory at Zurich, Switzerland, that he’d been seeing a lot of small shining bodies whooshing through the skies.

The astronomer wrote back that he’d been seeing the same things—and so had star gazer Sig Caporal at a Naples, Italy, observatory. They agreed that the ‘things’ were an insoluble mystery.

Nothing much worth noticing in the way so discs appeared in the sky again, Farnsworth said, until March 22, 1880. Just about a half-hour before sunrise, residents of Kattenau, Germany, said they saw an enormous number of luminous bodies rise from he horizon and careen across the sky.

‘These and other unusual occurrences have been well documented, but not one ever has been explained,’ Farnsworth said. ‘Scientists agree that they weren’t astronomical bodies.’

Farnsworth said he wouldn’t be surprised at anything the alleged saucers turned out to be. He’s president of the U.S. Rocket Society and is planning a trip to the moon some day.

‘Nothing surprises me,’ he said. ‘I wouldn’t even be surprised if the flying saucers were remote-control electronic eyes from Mars.’

Meanwhile, the Associated Press sent out—also on 8 July—columnist Hal Boyle’s attempt to make Fort and the flying saucers into a joke. The column began with an editorial note: “The following manuscript by Hal Boyle, who was last seen two days ago reading a copy of ‘Tom Swift’ on the steps of the New York Public Library, was found in a bottle in a perambulator in Central Park. The empty bottle apparently had fallen from a great hight.” It then went on:

ABOARD A FLYING SAUCER OVER PITCHER, Okla., July 8.—(AP)—Don’t tell me these flying disks are imaginary. Here I am in the middle of one, zooming around the American landscape like a boomerang.

These things aren’t disks or saucers at all. They’re built like a cowboy hat seven-stories tall.

I am a prisoner aboard a 1947 model ‘Flying Saucer’ from another plent. Let me explain:

I left the New York Public Library at dusk the other day and dropped into a quiet bar to wash down a warm vitamin pill with a cold bottle of beer.

Finishing it, I turned to a silent figure sitting next to me—the only other customer at the bar—and all but fainted. I saw a thing some eight feet tall, with one eye like a hard-boiled egg in the center of his forehead, and no visible mouth at all. He was naked, his hands were three-clawed and big enough for a Brooklyn centerfielder.

The green man’s yolk-yellow eye burned menacing red. One hand twisted one of a series of knobs on his chest marked “Slang. American,” and noiseless words drifted to me:

“Scram, Mac. But take along some beer, You’re going on a long ride.”

Then I found myself lifted and tossed sprawling. There was the sound of a door closing and a sense of lifting rapidly into space.

“Well, how do you like your first ride in a Flying Saucer, Orson Welles?” leered the green man. “You’re on the way to a place where there are more Martians than there ever were in New Jersey.”

“Look, this may be a flying saucer,” I complained, “but I’m not Orson Welles. I got this high forehead from wearing a tight hat.”

“Then who are you?”

“I’m his cousin, Artesian Welles,” I countered, “and who or what are you?”

“I’m Balmiston X-Ray O’Rune from Mars,” said the green man, and you have probably ruined my chance to win the sweepstakes.”

“What sweepstakes?”

“Why the sixty thousandth centennial running of the Universal Martian treasure Hunt Sweepstakes?” crossly grunted the green man. “this time there are 500 space ships competing. To win I have touring back twelve rare objects, including Orson Welles. Now somebody will beat me. It’s all your fault looking like somebody else.”

“What are the other items on your treasure hunt list?” I asked.

“I’ve just got a few things left to do in this country—like buying a new motor car, getting a nickel beer and a good five-cent cigar, and plucking a hair from the eyebrow of John L. Lewis.”

“Balmiston, old boy,” I said, “I think you and the other flying saucers are going to be here a long time. Your search is only beginning.”

“I’ll keep you hostage then,” he said. “You steer while I catch a little sleep.”

So here I am wheeling this blasted flying saucer back and forth between the Bronx [Ed note: think Fort], Santa Fe [ed note: think Roswell] and Seattle [ed. note: think Arnold].

If I succeed I’ll send out more details own the flying saucers tomorrow. If, however, the green man catches me again, well--

“Look out below, Peoria!”

There was a lot going on. In addition to Arnold’s sightings at the end of June, sightings continued to be reported across the country. The Associated Press dispatched a story about all the sightings on July 8. For those familiar with their saucer history, 8 July 1947 is infamous for being the day of the Roswell Crash. But only a day before, there had been another reported crash, near Houston. Norman Hargrave, a jeweler, supposedly found a 20-inch diameter, 6-inch thick disk on the beach of Trinity Bay. Imprinted on the object was an ominous message— “Military Secrets of the United States of America, Army, Air Forces M 4339658. Anyone damaging or revealing description or whereabouts of this missile subject to prosecution by the U.S. Government. Call collect at once, LD446, Army Air Forces Depot, Spokane, Washington.” Fortunately, also printed on it was the reassuring phrase “non-explosive.” A day after the report, Hargrave admitted it was a joke, but journalists were unsure since, as in the case of the Roswell incident, military personnel could not tell a consistent story.

Not that journalists were doing a whole lot better, continuing to harp own the connection between Fort and flying saucers, even relying on many of the same examples that had appeared in the earlier stories, but drawing many different conclusions as they became variously more acquainted with Fort. A story carried out of Washington—presumably the state—by the Associated Press on 11 July remixed the elements of the earlier stories in a much more jocular vein:

Don’t bother about those flying saucers anymore. They’ve been around before.

For the fact is that we poor mortals scare easily.

It used to be natural phenomena that gave us fits. Eclipses, for instance, obviously would frighten anyone who never had heard of such things.

And comets, the Encyclopedia Brittannica points out, always ‘have been regarded with mingled interest and apprehension.’

Written records show that in 240 B.C. the Chinese took one gander at Halley’s comet and figured the world was at an end.

It wasn’t, though.

The Roman philosopher Seneca tried to soothe people about the comets. ‘Someday,’ he wrote ‘there will arise a man who will demonstrate in what region of the heavens the comets take their way, why they journey so far apart from the other planets, what their size, their nature.’

But of course nobody paid any attention to Seneca, always a great one for talking through his laurel wreath.

Getting down to modern times and flying saucers, they first were seen 25 years ago on Brown mountain in North Carolina.

Charles Fort, who collects stories of freaks, tells about them in his book “Lo.” [sic]

The Saucers were globular-shaped then, and in those more leisurely days the [sic] floated instead of whizzed.

Henry H. Smith, the state editor of Bloomington, Indiana’s “The Pantagraph,” rewrote those stories, too, but he had obviously gotten his hands on the omnibus edition of Fort’s books, which allowed him to add some biographical detail and a not-quite-accurate digest of Fort’s ideas about science. This story appeared the day after Winn’s column:

If Charles Fort were alive today those ‘flying saucers’ would be just his dish—as following examples will show.

Prior to his death in the Bronx, N.Y. 15 years ago last May he completed four books that described and discussed reports of strange objects that flew through the air with the greatest of ease or dropped in the midst of puzzled people.

Some of the accounts were reported to respected scientific journals by men of considerable reputation in scientific fields.

Others were from popular magazines and newspapers. But these latter were no more ‘outrageous, infamous, ridiculous’ than the scientists’ reports.

Digging int he files in libraries in New York and London, Fort accumulated data covering a number of centuries nearly all parts of the globe.

Here are some earlier day things that may have been similar to the ‘oscillating disks’ of 1947:

May 16, 1808: Near Skeninge, Swedn, at 4 p.m. the sun suddenly turned brick red. At the same time a great number of round, dark brown objects seemingly the size of a hat crown appeared on the western horizon. For two hours they passed overhead and disappeared on the eastern horizon. Occasionally one fell to the ground.

When the place of fall was examined, there was found a film which soon dried and vanished. The bodies were described as having tails three or four fathoms long and their substance was said to be ‘soapy r jellied.’

July 12, 1907: In Burlington, Vt., three men standing on a street corner saw a ball of light or a luminous object fall from either the sky or a torpedo shaped object in the sky. At the same time they heard a tremendous explosion.

These men looked up to see a torpedo shaped body suspended in the air about 300 feet away and about 50 feet above the tops of the buildings. The outer surface of the object was dark and tongues of fire were seen to issue from it.

Nov. 17, 1882: At the Royal Observatory, Greenwich, England, a great cigar shaped or torpedo shaped disk of greenish light moved smoothly across the sky.

Sept 19, 1848: At Inverness, Scotland, two large bright lights were seen in the sky, sometimes stationary, occasionally moving at high velocity.

Feb. 9, 1913: In Canada, the United States and Bermuda and above the nearby sea, 30 or 32 luminous bodies were seen moving with ‘majestic deliberation’ across the sky in groups of fours, threes and twos abreast,resembling an aerial fleet.

Aug. 26, 1894: In North Wales, a disk from which projected an orange-colored body the looked like an ‘elongated flatfish’ was seen in the sky.

1838: In India, a disk, brighter than the moon, but about the same size, from which projected a hook-like form, was seen in the sky for about 2 minutes.

Fort also described the reactions of other men of science to reports of such phenomena by their colleagues.

The similarity of ‘scientific’ reaction in different periods and under different circumstances was one stimulus that set Charles Fort to writing about the things.

For Charles Fort was an arch enemy of of the dogmatic assertion.

Recent reactions to the disks or saucers have been quite similar to those Fort reported when he was alive. Those in turn resembled closely reactions of ‘scientists’ who lived prior to Fort’s birth in August, 1874, Albany, N.Y.

The usual reactions of scientists, other than those who reported unusual happenings, fell into the following classes:

1—Some denied, flatly, that anything unusual had happened. They asserted this with no basis except that the ‘occurrence’ had not happened in their presence.

2—Other scientists would at first express curiosity and interest in the event. Some would go to the scene and examine the evidence.

If no object could be seen, the affair was denied immediately and emphatically.

If some physical object was offered as proof of the happening, it was asserted by investigators that it ‘had been there all the time.’ Or it was described in such a way as to make it an ordinary object.

If, by some unusual circumstance, the object could not be harmonized with past experience in either of these ways it was sim;y ignored. Excluded. Quietly forgotten.

3—Others attacked the witnesses, If one person saw the thing he was the victim of delusions or hallucinations or optical illusions.

If several persons saw the happening, they were victims of hypnosis or mass hysteria.

Scientists apparently forgot that if these two categories of witnesses are excluded from testifying in all instances, there would be no basis for any science.

4—If the object persisted, it was packed off to a closet or case in some museum, tagged with a card explaining its existence in a mundane way and left there.

5—If the witnesses persisted, they were ridiculed into silence.

6—If the scientist witness were persisted in seeking discussion, he was ostracized into silence.

These actions made Charles Fort angry. It was typical American anger over suppression of free discussion. Therefore he wrote his books.”

On 14 July, an unnamed journalist—this too may have been a wire story, though there is no indication—offered the most informal assessment of Fort and flying saucers In Neosha, Missouri’s “Daily News.” It was also, though, the first to go beyond his observations about aerial phenomena and mention his cosmological theories, a suggestion that this writer had also obtained a copy of the omnibus edition:

It’s just too bad all the folks getting bug-eyed over flying saucers these days can’t meet Charles Fort.

Charlie could have calmed their quivering nerves in no time. ‘Flying saucers?’ he’d ask, ‘Why it’s nothing at all . . . an old story, really.’ And Fort could sit down and prove what he was saying.

He’d point out that a king size flying saucer . . . . about as big as a dining able . . . zipped across the skies over Niagara Falls back in 1933. Five years later startled natives of New Zealand saw something that looked like an oval of slivery vaporous material hang motionless over their heads for a moment, then began to sway from side to side, and finally shot out of sight at rocket speed.

Although Charles Fort is no longer around to tell you himself, he left four books behind (titled Lo[sic], Wild Talents, The Book of the Damned, and New Lands) to describe all the curious things world neighbors saw in the sky.

Take, for example, the ‘Flying Trumpet,’ seen over Mexico in July of 1874 . . . a huge thing that dangled some 500 feet in the air, seeming to swing gently from an invisible string. It was clearly visible for five minutes.

Or consider the story of the fiery cartwheel seen over Sussex England, in 1855 . . . A flaming pinwheel that rose slowly into the midnight sky and remained visible for an hour and a half.

There was a terrific furor in this country in April of 1897, when observers all over the nation reported sighting a cigar-shaped object with great wings, resembling an enormous butterfly. Pop-eyed farmers in the middle west said the flying cigar was illuminated by searchlights and decorated with red and green lights, Of course, jokesters hopped aboard that bandwagon, too, and there were reports from here and there amplifying the original yarn. One man even said he say [sic] the flying cigar decorated with an American flag . . . just like the Denver man who saw our modern day flying saucer with a flag on it.

The flying cigar seemed to prefer the midwest and it was several weeks before all the excitement died down. To this day, no one has offered a factual explanation for the episode.

One interesting thing about these unusual celestial sights is that a century ago they were more apt to be cigar-shaped, or triangles. Also they moved a great deal slower . . . 20 to 30 miles an hour . . . and some just dawdled in space, going nowhere. With these last laggards, it was a case of ‘Now you see it, now you don’t.”

If you think most saying saucer views are probably tipsy, listen to this. In July of 1907 a Vermont bishop reports the following:

‘I was standing on the corner of Church and College streets in Burlington, Vermont, in conversation with ex-Governor Woodbury, when . . . without the slightest warning . . . we were startled by a terrific explosion. Raising my eyes and looking eastward,’ the bishop continues, ‘I observed a torpedo shaped body suspended in the air about 50 feet above the buildings. It was about six feet long . . . . dark in color with tongues of flame issuing from spots on the surface, which resembled red-hot burnished copper.’

The bishop concludes, ‘Still burning, it moved slowly over Dolan’s store and vanished . . . as far as I know, it was never found.’

That’s only one of the fabulous items collected by Fort in his life-long career of investigating the world’s visual oddments.

You see, Fort believed that among other things, there is a shell around the universe. He believed what we think of as stars were actually openings in the shell. Hanging over this shell, Fort though there were other universes with superior inhabitants who occasionally used such odd things as are seen int he sky to actually fish for is!

So the next time you see a flying saucer . . . duck. It may have a fish hook in it.”

That same day, the syndicated columnist Jay Franklin brought Fort together with the current flying saucer fad, adding that Fort had suspicions about alien civilizations—thus connecting flying saucers to extra-terrestrials:

So far this column has not seen any flying saucers—although sorely tempted to rush into print with the report that a flying saucer painted with a hammer-and-sickle and with a Russian-looking aviator at the controls passed over the National Press Building.

The explanation of this phenomenon, which is reported by a number of trustworthy witnesses as well as by a number of obvious cranks and publicity seekers, is beyond me. My own macabre inclination runs in favor of the theory of the late Charles Fort, who spent a life-time gathering data of just this kind.

Fort compared us to fish at the bottom of the sea, trying to explain the debris dropped now and then from passing ships. His own belief was that the earth is ‘owned’—as a colony or hot-bed or even a pit—by some or several groups of extra-terrestrial being whose nature was entirely unknown to us. In his life-time he massed a large amount of authenticated data which defied any other analysis pointing out that the role of science was simply to deny the existence of any data which it could not explain.

Another rule of science, he reported, was to dismiss with a scientific label any inconvenient fact. This rule is illustrated by the solemn pronouncement that the flying saucers are ‘moscae volantes’ (Latin for ‘flying flies’), which is termed a rare optical phenomenon, that causes the observer to image [sic] that he sees objects moving rapidly out of the limits of ocular vision. This explanation, it can be pointed ou, explains noting, since the objects might not be imaginary, and in this particular case the occurrence of the flying saucers has been so widespread that the phenomenon can no longer be described as rare. Since the sight of the saucers has been at widely separated points and times by entirely different observers, the other explanatiou[sic] of ‘mass-hallucination’ cannot hold water, though some credit can be given to ‘mass-suggestion’ in the numerous cases involved since the disks were first reported.

One thing is clear: Unless the Army has developed secrecy and security regulations to an unheard-of degree, this is not an example of experimental military aircraft. Also, since none have crashed, it can be argued that Army pilots are not at the controls. The absence of any trace of these saucers on earth suggests that Fort may be right, though this column is puzzled buy the statement that they couldn’t possibly come from outside the earth’s atmosphere since they would have burnt to powder in the process of getting inside the ionosphere, the stratosphere, etc.

It was my impression that rocket-scientists were already calculating on how to pierce through to the outer space and had decided that it was entirely practical, which would not be the case if missiles were sure tone burned to powered in the perilous passage.

For finally we must fall back in the conclusion that we know nothing of the world and of the universe except through our five senses. These senses we know to be limited—extremely so even by comparison with the senses of observable animals. t is entirely possible that the thing we see, smell, hear, taste and touch is entirely different from the thing itself. For that reason, this column preserves a completely open mind on the reality of these flying saucers that have hovered over the country for the last two weeks.

After that column, Fort dropped out of the news for several months, until another indicated columnist, Billy Rose, revived him for a December piece. The story may have been inspired by the Fortean Milton Subotsky, who was then on Rose’s staff:

“After reading about the break-up of the Big Four Conference in London, I’m thinking of joining the Fortean Society. This is an organization dedicated to the snicker and the sneer. Its members maintain that it rains frogs; that interplanetary cargo ships whiz through space and sprinkle the earth with three-legged midgets; that 1,000-foot monsters play tic-tac-toe on our ocean beds, and that people occasionally burst into flame for no reason at all.

Am I talking about a nutsy-dopey-crazy outfit? Hardly. Its charter members include Oliver Wendell Holmes, Theodore Dreiser, Havelock Ellis, Clarence Darrow, Ben Hecht and Alexander Woollcott. It was forme din 1931 and novelist Tiffany Thayer has been its president since it started. It publishes a monthly magazine called Doubt. Its symbol is a big question mark. The fraternal salute of the members is five fingers in front of the nose.

This society of myth-makers was formed to popularize the teachings of an intellectual spit-ball artist named Charles Fort. Fort, who died in 1932, devoted most of his 68 years to poking holes in popular beliefs. He insisted that the brain cells were entitled to a New Look each year. ‘I can conceive of nothing in religion, science or philosophy,’ he wrote, ‘that is more than the proper thing to wear for awhile.’

Charles Fort wrote four books—‘The Book of the Damned,’ ‘New Lands,’ Lo!,’ and ‘Wild Talents.’ Theodore Dreiser thought Fort ‘the most fascinating literary figure since Poe.’ Ben Hecht called him ‘the Apostle of the Exception,’ and ‘the Jocular Priest of the Improbable.’ He commended the writings of this dogma dynamiter for their ‘onslaught on the accumulated lunacies of fifty centuries.’

Membership in the Fortean Society is open to all. On its roster you will find Democrats, poets, Republicans, astrologers, chiropractors and FBI agents. It fronts for lost and unpopular causes, adherents of the flat-earth theory, anti-vaccinationists, and people who believe it snows upside down. The Fortean Society rates Einstein’s Law of Relativity with the Volstead Act.

Each year the society confers an award on ‘the individual who most effectively assails the currently ascendant dogmas.’ The award is a small replica of a famous fountain which stands in a square in Brussels and represents the Fortean attitude toward the world. The recipients have included such tradition ticklers as H.G. wells, Carl Van Doren, Bertrand Russell and John Dewey.

The society occasionally distributes books to elevate the mass mind. The one I’m buying myself for Christmas is entitled, ‘Rabelais for Children.’

Now, why should the break-up of the Big Four Conference in London lead me to join a society dedicated to the exception, rather than the rule? Very simple. If I’m going to go down the drain, I may as well go down laughing. In 1945 the clear thinkers finished killing 30,000,000 people. If that’s all our clear thinkers can show me, I might as well join up with the loonies. At least their jokes are better.

I’m sending in my application to Box 192, Grand Central Annex, New York City. I don’t know where the society holds its meetings. My guess would be the top branches of a tree in Central Park. But wherever it meets, I hope to be there the next time the members convene.

It’s a chinch the chit-chat will be one a higher plane than [Tehran], Yalta and Potsdam.”

*********

It still seems most likely to me that Marcia Winn came to Fort through Farnsworth, though that cannot be determined exactly. What stands out, though, is that she—unlike anyone until Billy Rose—was making a political point about the Fortean Society, first its perpetual peace plan, and then, later, about flying saucers. She classed herself a Fortean, and seemed to appreciate its skepticism. But she was using the weight of evidence gathered by Fort to make a different, political Fortean point: that the flying saucers should not be a pretext for martial behaviors. Whatever they were, they were not new, likely not a threat, and certainly unconnected to the Cold War. Fort was a complement tot he Tribune—and apparently her own, certainly her husband’s—isolationism.

The Fortean Society members I have studied to this point have tended libertarian, and, more specifically, left libertarian, which is a political position largely obscured in today’s political and media environment. Yet, Thayer’s dyspepsia, and stance against science and accepted wisdom could also be used by rightists, and there was certainly a number of connections to those with Fascist sympathies. Winn and Morgenstern are not even closely allied with Fascists, as far as I can tell, just old-fashioned isolationists, conservative in their outlook, who found Thayer’s version of Forteanism and pacifism comforting.

Winn had one more connection with the Fortean Society, a mention in Doubt 19, October 1947. This was Thayer’s concession to the readership, which wanted coverage of the flying saucers, though he was not interested in the subject (and, indeed, came to hate it for lumping the many different kinds of aerial anomalies under a single rubric). Mrs of this issue was taken up by his essay “The United States of Dreamland,” which framed the many (many, many) reports of flying saucers that had been sent in to him. His argument was that the press—the media—created the reality in which people lived, the dreamland in which they operated, unconnected to reality. As part of the evidence, interestingly, he pointed to Pearl Harbor—which he said most people knew was coordinated but he government, as Morgenstern argued that very year—his book had been published in January—but the press dismissed it. Just as the press was trying to erase, or laugh into oblivion, reports of flying saucers. In an extended opening, Thayer wrote,

“‘Hysterical’ is the term invented for the doctor’s use to shut your mouth when your wife is sick and he doesn’t know what’s wrong with her. For most rough and ready purposes it denotes the mildest form of insanity. ‘Hysterical’ persons are not really crazy, they just act as if they were. By extension, typical of this era of loose generalizations and to hell with details, the term has come to be applied to shut all our mouths whenever anything is going on which Science doesn’t understand. The editors of the freeprez have borrowed the gag from the doctors, and thus--by extension again--they place themselves on a level with the medicine-men, above the masses to which they minister, immune to the effects of their own jargon, amulets and incantations.

“One detail commonly overlooked by doctors and editors who lift themselves to the astral plane by their own bootstraps is the perniciousness of self-satisfaction. No rose that blows can be so captivating, so enchanting in its fragrance, as are--to an individual--the odors he creates himself. This matters very little in the case of a doctor in love with his own diagnosis. If your wife’s ‘hysteria’ kills her, that’s no great loss to the world, whereas the fate of nations, civilizations, of the planets in their courses, may depend on the editors’ whims. The stench they raise daily is their ozone and it affects them much like opium, so that by constantly inhaling their own gasses they live in a perpetual dream-world of their own creation. Limiting ourselves to the local scene, they have set up the United States of Dreamland, whence this essay derives its title.

“If the numerous editors created private worlds, like the thousands which revolve in Bedlams everywhere, they would be shut up with the other maniacs who think they are God, and although we might deplore their sad state, we should be protected from their violences. Unfortunately for us, the great editorial delusion does not create private worlds. Its false appetites are not satisfied until vast numbers of the sane are behaving AS IF the synthetic cosmos of the editors’ diurnal vaporings were bona fide. Like ‘hysterical’ women, the editors generally retain some faint awareness of reality, and like maniacs, they are cunning. Their faint awareness of reality is their yardstick by which they measure their power over the sane. Their cunning has inspired them to unite their efforts to extend that power by enforcing the delusion of a single dreamworld universally instead of a different one in each circulation area, and the means they have devised to this end are called the Associated Press, the United Press and the International News Service.

“These press associations and their member publishers own or control the means of broadcasting the ‘news’ by radio as well, so that any appearance of competition between the two media is the sheerest illusion. You never have heard a scrap of news over the air until after it was for sale, printed on the street, with the exception of sports events and a few rare accidents which have occurred under the eyes of an announcer already on the air. In this latter class, the burning of the Hindenberg and the crash of a plane into the Empire State Building are notable examples.

“Yes, the means of general communication in the world today is a monopoly held by a small group of madmen who call everybody else ‘hysterical’ and do everything in their power to make that wish-thought a fact. Rational humans who, conceivably, might wish to compare notes about events in the real world have not the slightest chance to do so. nowhere on the face of the earth today is there a single publication (of any significant circulation) which is not dedicated to the perpetuation of some pipe dream. So that in good sooth (for all practical purposes) the United States of Dreamland IS the reality. We, the people, have had forced upon us a notoriously false and scurrilous wood-pulp soul. And what the Devil do we do about it?

“Suppose, for the sake of argument, that the majority of the population were ashamed of the picture of ourselves which the papers send abroad. How would we go about changing it?

“The vast majority of us knew that Pearl Harbor was a put-up-job agreed to by the U.S. Government expressly to make the public ‘hysterical’ (only at that time the term was ‘war-minded’), but what could we--and what did we--do about it?

“Writing letters to editors doesn’t do any more good than writing them to Santa Claus. Nailing their lies doesn’t stop the chain-effect the lies have set in motion. No matter what percentage of the public is aware of a published falsehood, that awareness practically never gets into print, so that, say, 90% of the people in New York don’t know and can’t find out what 90% of the people in Chicago are thinking. Polls of ‘public opinion’ are engineered to substantiate any nefarious noxious nonsense the editors wish to foist upon us. The only publication of any potency which consistently exposes their frauds is IN FACT, a weekly, and IN FACT has an ax of its own to grind, and so circulates principally among groups which would like to control the United States of Dreamland, but never, never, never would permit the views of the masses to circulate freely. Nor does the limited potency of IN FACT stem the flood of falsehood in the slightest. On the contrary, each little exposure calls forth a smothering blanket of taller tales, so that the great stock of imposed hallucinations us weekly being squared to the seventh power.

“Thus was the world led into ‘war.’ Thus were the masses taught to fear ‘atoms.’ Thus--most recently--was a grand series of Fortean phenomena laughed out of the editors’ Dreamland. Reference is to the data which newspapers grouped hysterically under their flying ‘saucer’ or ‘disk’ scare-heads.”

There followed a list of hundreds of reports, including those of Kenneth Arnold, including coverage by the “Chicago Tribune,” to which Thayer clearly subscribed, or, at least, followed closely. Also among these was the AP report from Chicago about Forts rare book—reported, Thayer said, by “a thoroughly misinformed AP man,” though as we can see, it may have been a woman. He called out Farnsworth’s quotations, too. Thayer notes that he spent much of the day of July 7 on the phone giving permission to radio and newsprint to quote Fort as well as answering questions about him—which may also have been a source of some of the information that appeared in articles from later July. The events in Roswell were noted, and the official explanation that the vehicle was a weather balloon roundly criticized as unbelievable.

Winn was among those credited with contributing to the issue. There was no first name, but it was almost certainly Marcia. Whether she sent in the material or not is hard to know. But she was listed as a member, which means that, at least for 1947, she contributed her dues. Maybe she continued paying—probably not—but whatever the case, she was never mentioned again.

Morgenstern was never mentioned at all, although the gist of his book was certainly something that Thayer accepted—in whatever way he accepted anything. And I have no proof that he was a member of the Fortean Society. However, he knew about Fort, and on 3 November 1973—about two years after his retirement—wrote for the Tribune a piece that, once again, connected Fort and flying saucers:

Recently there has been a rash of reports about the sighting of Unidentified Flying Objects. Two fishermen in Mississippi started the latest round by saying they were taken aboard a space ship and examined. Gov. John Gilligan of Ohio announced soberly that he had seen a UFO. I have never encountered what George Wallace of Alabama calls ‘pointy-headed’ creatures. I carry my UFOs around in my own head, where they whirl about confusing me even fourth.

Some of these objects have been implanted by surprising and even eccentric acquaintances. What would you say if, as once happened tome years ago, a Hearst Sunday editor given to betting the races and quaffing libations, informed me, “God came to me in a vision. He said to me, ‘Murdoch, don’t play the horses. You can’t win’”?

I have had editors who said such things as “She wore her widow’s tweeds,” or “They lived in a rumshackle house,” or “He showed the yellow feather.” These things get stored upstairs and bounce about to interrupt the logical process. It is difficult enough sorting out ideas, thoughts, and impressions without having to strive with unsolicited encumbrances.

The other night I thought I heard it said in a television commercial, “the Kremlin has always enjoyed popularity.” But that, obviously, could not be true. It had to be a motor car called the Gremlin. Yet I am afraid that the original misconception will join the collection I already carry around in my belfry.

When, a few years ago, Dr. Edward U. Condon made a scientific study for the Air Force of the validity of reports of UFOs, his point of departure was a consideration of the psychological makeup of those submitting such reports. Yet serious people have seen many things they cannot understand.

More than 50 years ago Charles Fort began writing a series of four books providing a compendium of the observed, the reported, and the unexplained: “a procession of data,” as he said, “that Science had excluded.” When these were brought out as a single volume in 1941, his editor said that Fort “believed not one hair’s breadth of his amazing ‘hypotheses.’” And Fort himself wrote of one of his books, “I am offering this book as fiction—if there is fiction . . . I never write write about marvels.” Then he proceeded to offer a chronology of what most people would consider marvels.

There were reports of green suns and blue moons, of black rains, of hailstones the size of elephants, of rains of frogs and coffins coming down from the sky. And there were cryptic comments about “what befell virgins who forgot to keep fires burning in an earlier age.” A typical Fortean observation: “Not a bottle of ketchup can fell from a tenement house fire-escape in Harlem without . . . affecting the price of pajamas in Jersey City; the temper of somebody’s mother in law in Greenland; the demand, in China , for rhinoceros horns.”

But along the way there were early reports of what we call UFOs. Apparently Fort put some credence in them, for at least in the form of a question he suggested, “If lights that have been seen int he sky were upon the vessels from other worlds, perhaps there are inhabitants of Mars who are secretly sending reports on the way of this world to their governments.”

One of the sightings in 1848 described two wheels of fire which shivered to pieces the topmasts of a vessel. The Danish Meteorological Institute report two instances of revolving horizontal wheels, one in the Straits of Malacca in 1909 and the other in the South China Sea in 1910. There are eight pages of reports from reputable people of observations of ‘strange celestial visitors.’

These date back more than 170 years and sightings were reported from all over the world. The objects were variously described: an orange-colored body that looked like ‘an elongated flatfish’; disk about the size of the moon, but brighter; large luminous body, almost stationary; thing with oval nucleus and lines suggestive of structure; luminous object, size of full moon; something like a gigantic trumpet, oscillating gently; torpedo-like bodies resembling Zeppelins; “a formation having the shape of a dirigible,” cylindrical, but pointed at both ends.

Many such sights were reported by scientists at the Royal Observatory at Greenwich and other national observatories, and on some occasions things were dropped from the sky.

“my own acceptance,” Fort writes, “is that super-geographical routes are traversed by super-constructions that have occasionally been driven into the earth’s atmosphere.” He thinks that, upon entering the atmosphere, “these vessels have been so racked that had they not sailed away, disintegration would have occurred that, before leaving this earth, whether in attempted communication or not, or in mere wantonness or not, dropped objects, which did almost immediately disintegrate or explode.”

Take your choice. I can do without UFOS, for I already have enough unsought visitors roaming around in my upstairs.”

The article was obviously meant to be taken lightly, poking gentle fun at the very idea of flying saucers—and the need for them, when the world itself was already so askew as to provide plenty of marvels—as well as Fort’s ideas, which he acknowledged were not meant to be taken as anything more than a kind of fiction. But there are serious questions behind the article. One wonders, for example, if Morgenstern nursed an interest in Fort since the 1940s. Or had he merely come across him again, perhaps recapturing faded memories. I like to think—though this is pure speculation—that he was piqued by the renewed interest in flying saucers and went into the paper’s morgues, where he found his wife’s previous writings on the subject, and on Fort, as well as the other AP stories being sent out around that time. Obviously, there are only a limited number of examples one can draw from Fort, but it is striking how similar his list is to those of 1947. One wonders, then, if Morgenstern, at least for a moment, was again in the presence of his wife: one of those things whizzing through his mind, a constant presence, a flying saucer.

The 1940 census had her living alone, renting a place. She had suffered some—she lost a brother and a sister separately in the 1930s, and her father passed in 1941. She was not a hermit, though. There’s a story that in 1942, when he moved to Chicago for a time, she spent the night of a part necking with the composer John Cage. That year, she also took over a column “Front Views and Profiles.” Winn edited the daily-feature, and contributed regularly. I have read a bit of her output, but not made a full study of it. She clearly moved in artistic circles; in 1945, she wrote a long story for the paper’s Sunday magazine extolling the virtues of early American landscape painters. It was reprinted and sold by the Art Institute of Chicago. She had conservative inclinations, though, too, at least politically: “Taxes” magazine saw fit to republish one of her stories. In 1943, she was sent on assignment to Los Angeles, from which she wrote an exposé of Hollywood’s libertine ways, and also got a front seat view of the so-called Zoot Suit Riots. It’s clear that in the 1940s, though she was living alone, in a city distant from her family; though she had suffered personal loss; she had a rich life. Then, in 1945, she added to it, marrying George Edward Morgenstern.

Morgenstern lacked Winn’s deep American ties. He was born 26 May 1906 in Chicago to Jacob (aka John) Morgenstern and Nora Murphy. The elder Morgenstern had been born in Ohio to German immigrants; Nora had been born in Ireland. The two married in Chicago some dozen years before George entered the world. He was the second of two boys, nine years younger than William. Jacob made a living as a printer. The family lived in Oak Park, and the two brothers wen to high school there, where Bill went to work on the school newspaper and recruited his brother to do the same. They covered school sports. After graduation, George went to the University of Chicago, where he continued covering sports and working up to editor of the campus magazine “The Phoenix.” Journalism crowded out other aspects of Morgenstern’s life, so that he became a part time student, also writing (on sports) for the Herald-Examiner, as well as working as a rewrite editor there and reporter, covering some of Al Capone’s tax evasion trial. He did finally graduate, in 1930, with highest honors.

It’s not clear to me what Morgenstern was up to in the 1930s. Probably he was still attached ti the Herald-Examiner—though it’s not specified, it makes sense with the rest of his career. He also seems to have tried his hand at book writing. In the 1930s, there are copyrights to Morgenstern for books on “Abe Mitchell and the Rover Boys”—one subtitled “Abe Mitchell Goes to College,” the other “The Big Game.” These came out in 1934, the year Winn joined the Tribune. We knew they were the work of this particular George Morgenstern because the copyright address is Oak Park, Illinois. I have not seen these and am not even sure any copies exist: I can only find the copyright notice, nothing in library catalogs. (It’s worth noting “The Rover Boys” was the name of a series of books published from 1899 to 1926, thirty in all. Abe Mitchell is the name of a famous golfer. What the connections are here are impossible to know.)

In 1939—the year that the Herald-Examiner stopped publishing—Morgenstern moved to the Tribune as a reporter and rewriter. In 1941, he became an editorial writer. His journalism career was interrupted by two years of service during the War. In 1943 and 1944 he was with the Marines, discharged as a captain. (That’s what all the paperwork I have seen says; his headstone gives him the rank Lieutenant Colonel.) In addition to everything else, his military service would have been another connection with Winn: her father had served in World War I, and her brother was in the military. Morgenstern married Marcia Winn on Saturday, 15 September, 1945, in a small ceremony attended only by friends and presided by a Presbyterian Minister. Evidence of just how close the two journalists were to their newspaper and its publisher, the wedding was held at Colonel McCormick’s home, and he gave the bride away. The reception was held at the Southside apartment where the new couple would live. Winn opted to keep her maiden name for professional reasons.

With the marriage, Marcia’s career slowed down some. She gave birth two a daughter, Marcia, in 1946. At the end of 1948, she partially retired from newspaper work; in 1949, she gave birth to her second daughter, Nora. Meanwhile Morgenstern was making public waves. In 1947, he published a revisionist history of America’s entry into World War II, “Pearl Harbor: The Story of the Secret War.” It argued that Roosevelt was likely well aware of the coming attack, and wanted it as an excuse to get America involved in the conflict. The book won plaudits among other revisionist historians—such as Charles Beard and the former Fortean, Harry Elmer Barnes—as well as the socialist (and nominal Fortean) Norman Thomas. As far as I know, it was not taken up in the pages of Doubt, but retreads of the argument would help push another Fortean, the science fiction writer Robert Anson Heinlein, toward the political right.

Morgenstern’s work set the pattern of later World War II revisionists. An abbreviated essay digest appeared in Barnes’s edited volume “Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace” (which, intentionally or not, echoed Thayer’s Perpetual Peace Plan). He also wrote for the right-wing (and still barely isolationist) magazine “Human Events,” concluding, “An all-pervasive propaganda has established a myth of inevitability in American action: all wars were necessary, all wars were good. The burden of proof rests with those who contend that America is better off, that American security has been enhanced, and the prospects of world peace have been improved by American intervention in four wars in half a century. Intervention began with deceit by McKinley; it ends with deceit by Roosevelt and Truman.” By accounts, Morgenstern’s theories fit well with the tenor of McCormick’s editorial page, which was revisionist and remained isolationist. In time, Winn, too, came back into the journalistic fold at the newspaper, beginning a twice-weekly column on parenting (“You and Your Child”) in 1950 that was syndicated in some thirty papers. In 1954, she published “We Learn about Ourselves: Primer for Parents: a Guide to the First Six Years of Life,” through the “Encyclopedia Britannica.” She also returned to reporting.

In 1955, Colonel McCormick died; Morgenstern was given the job of writing his obituary, but could not do it—their friendship was too dear—and so Winn completed it for him. She also continued McCromick’s quixotic practice of spelling reform—a favorite of some Forteans, such as George Starr White. The newspaper never made their commitment explicit, or explained what it was doing, but rather simply used altho instead of altho, for example, or frate, frater, and sodder. The paper’s interest, though, seems to have declined after its peak in 1955. Winn went on to other matters. In 1957, she interviewed the thrill killer Nathan Leopold (of Leopold and Loeb fame) who seems to have come to terms with his act and took quiet pride in the prison work he did. The interview sparked widespread interest—it got Winn mentioned in “Time” magazine and won her journalistic awards, as well as prompting some calls for Leopold to be released.

It was around this time that Winn became ill. Her last few years saw her in poor health. She died 15 August 1961 in a Wake Forest Hospital. Her daughters were 12 and 15. She was only 50.

George soldiered on at the Tribune. In 1969 he became editor of the editorial page. In 1971, he retired, though he continued to contribute occasional editorials. In the early 1980s, it seems, he moved to Denver to be closer to his daughters and two grandchildren. He died 23 July 198. George Morgenstern was 82.

**********

It seems likely that of the couple Marcia Winn found the Fortean Society—before she found Fort—probably through an interview with Robert L. Farnsworth, the Fortean obsessed with colonizing the moon for America. Farnsworth started making Chicago newspapers in 1945, with his petition of the government to use atomic energy as a fuel for moon-bound rockets. During the post-Kenneth Arnold flying saucer flap, he was quoted in an article mentioning Fort as pioneering study of this phenomena in a Tribune story—likely done by Winn—that was picked up the U.P. and sent around the country.

It was this year—1947—that comprises the entirety of Winn’s contribution to Forteanism. She added a little to the Society’s publication directly, and did more by promoting it. Going beyond quoting Farnsworth, she seemed to find something of excellence in the Society and chose to advertise it. In March—before Arnold’s sightings, but after Farnsworth had been in the paper for a couple of years—Winn devoted one of her “Front Views & Profiles” columns to the Fortean Society, and its “Perpetual Peace Program,” which meshed well with the paper’s isolationist and anti-war stance. On the 29th, the paper published her piece:

P.P.P.

The Fortean society prides itself on being the only organization which has as its sole aim perpetuation of dissent from dogma. The title of its magazine gives a clew [Ed. Note: the spelling was not unusual at the time, but a hint at the spelling reform] to its theories, for it is called Doubt. The D is cut out of what seems to be the Einstein theory, the O is cut out of that celebrated picture of the Big Three at the Yalta conference, the U and the B are beyond us, and the T is cut out of the stock market reports. The society even doubts the Gregorian calendar, which the rest of the world uses, and dates its calendar from what we know as 1931 A.D.. To them that year is 1 FS [Fortean Society][Sic: its Fortean Style], the year of its founding. It also uses 13 months.

Enough of its background. What we want to pass on is its Perpetual Peace Plan, referred to by Forteans as P.P.P., which is based the premise that to maintain peace under the profits system is very simple. Just go to work for spending war-like sms of taxes and collecting warlike sums for charity. Give it all the aura of immediate necessity. P.P.P. so far has 12 planks:

A cyclotron in every high school.

An atom busting plant in every middlesex [some of the Forteans are English] and village.

Every waitress a Ph.D.

Every laundress a B.A.

A standing army of 10 million translators to translate every book ever written into every other language.

Subsidies for publishers to issue these books and for booksellers to see them on every corner.

A 200 inch Palomar White-elephant telescope at every crossroads.

Completion of the sculptured heads which Gutzon Borglum began to blast out of Mount Rushmore in the Black Hill and the extension of similar art to every bald knob in the world’s mountain chains. [Thereby using up all the explosives.]

Extend the experiments of J.B. Rhine with cards and dice, setting up Extra-sensory Perception laboratories at every public gathering.

Supplant all lie detectors in police stations and courts of law with motion picture cameras, lighting equipment, and sound recording devices tomato permanent, audible, visual records in close-up of all principals and witnesses in every trial. [Would spend untold piles of money and end sleeping judges and/or juries.]

Institute in all grammar schools, as an aid in vocational guidance, the Sheldon system for classifying physique and temperament. [This requires three still photographs of every child, one before, one behind, one profile, all nude.]

Finance R.L. Farnsworth, the rocket man, in a race with therapy to the moon.

If, however, the tax eaters demand ‘just one more’ war, the society suggests an improved war: Instead of sending Russian boys to the United States to wreck the place, and sending our mean to Russia to do the same, let each stay home and do its damage. The net result, the society asserts, is the same: Rubble and a rebuilding boom. The only argument that can be raised against it is its economy.”

A few months later, on 11 July 1947, the paper ran another of Winn’s “Front Views & Profiles” columns devoted to the Society:

“Pie in the Sky?

One colleague says those soft drink people are trying to make use concentrate on the night skies. [Ed. Note: Bay Area Fortean made the same suggestion around the same time.] Another, a loyal son of Nebraska, says the university there holds the world’s discus championship and is indulging in secret practice. As a Fortean [‘The sound Fortean holds all estimations of value in perpetual suspense’] who has so far seen nothing in the night sky more alarming than the moon, we can only refer you to the works of the late Charles Fort and say that there have been disks before this.

Science could never explain the phenomena Mr. Fort chronicled. That is why he wrote them. It wasn’t that he didn't believe beyond and around it. His role was to dissent from dogma. No, try again. Science often did explain the phenomena. It explained them _away_. Mr. Fort contended you couldn’t do that. They existed; ergo, they could not be ignored.