Too little known, too important to ignore: the story of a Fortean.

I know virtually nothing about the personal life of Judith L. Gee, not even what the L stood for. She lived in London. She was born sometime between 1880 and 1920—the earliest letters of hers to national publications I can find appeared in the mid-1940s, the last in the late 1970s. She was married, signing her letters Mrs. She had liberal inclinations and was opposed to anti-Semitism. She was interested in parapsychology and allied fields. She could be somewhat imperious. She was a stalwart Fortean, and also an object of ridicule among some of the men who ran the Society. C’est ça.

Apparently, she was introduced to the Fortean Society by Harold Chibbett, though her connections to Fort seem to date more deeply. In an undated letter to Russell—but from 1948—Chibbett noted, “Talking about Forteans, I have just uncovered a rabid female of the species, whom you might be able to collar as a member if she is not already one. J. L. Gee, 27a, Goldhurst Terrace, Hampstead, London. I am going along to see her in a few day’s time, and will let you know further.” There was no more correspondence from Chibbett on the matter, but Gee herself wrote to Russell on 27 July 1948:

I know virtually nothing about the personal life of Judith L. Gee, not even what the L stood for. She lived in London. She was born sometime between 1880 and 1920—the earliest letters of hers to national publications I can find appeared in the mid-1940s, the last in the late 1970s. She was married, signing her letters Mrs. She had liberal inclinations and was opposed to anti-Semitism. She was interested in parapsychology and allied fields. She could be somewhat imperious. She was a stalwart Fortean, and also an object of ridicule among some of the men who ran the Society. C’est ça.

Apparently, she was introduced to the Fortean Society by Harold Chibbett, though her connections to Fort seem to date more deeply. In an undated letter to Russell—but from 1948—Chibbett noted, “Talking about Forteans, I have just uncovered a rabid female of the species, whom you might be able to collar as a member if she is not already one. J. L. Gee, 27a, Goldhurst Terrace, Hampstead, London. I am going along to see her in a few day’s time, and will let you know further.” There was no more correspondence from Chibbett on the matter, but Gee herself wrote to Russell on 27 July 1948:

“I have, I think to thank you for my copy of DOUBT, which I have just received and devoured.

“The post mark is Liverpool, but I am in doubt, whether I have to thank Mr. Chibbett, or the Forteans of New York for passing me on to you. Do please settle this doubt!

“Mr. Chibbett, who has been to see me, has mentioned your name as chief Fortean in England. But, I had written to New York for a copy of their magazine, that is why I question whom I have to thank.”

Although it cannot be stated definitively, the reason for Chibbett’s connection to Gee seems obvious in retrospect: they ran in the same circles. She had written to letters to the British “Occult Review,” unseen by me, which very may have led Chibbett to her. In a later letter to Thayer, Gee said that her husband had seen Charles Fort during his London years, and new others from the neighborhood who remembered him, suggesting an abiding interest in the anomalous. She was keen to continue connecting with the Society and Forteans more generally, asking Russell in her letter how to convert English moneys into $2 American and if he could lend her the entire earlier run of Doubt for an “indefinite period” so that she could “read them in digestible comfort.”

Russell seems to have written back fairly quickly, with a letter that does not survive, dunning her 10 shillings and telling her to see Atlantis Bookshop for back issues of Doubt. She replied on 13 August, thanking him, noting that she had received copies of Doubt from America (as well as other American magazines, which left her “up to my ears reading them, and growling at interrupters”), and inviting him to visit some time. She said that she knew the Atlantis Bookshop and its owner—Michael Houghton—quite well, but wasn’t sure she could afford to by any books at the time, and so was still anxious to borrow relevant tomes. She also wondered what had become of N.V. Dagg’s magazine “Tomorrow,” presumably asking because Russell was a frequent contributor. She had subscribed and enjoyed the periodical until it became blatantly anti-Semitic, at which time she dropped it and “suspect[ed] anything that comes from that stable.”

Again, Russell seems to have replied diligently, though perhaps less kindly—once more, the letter does not exist—apparently bristling at being called “chief Fortean” in England and taking issue with Gee’s interest in borrowing books. (Borrowing was a long-time bugaboo of Russell’s, and something he held against science fiction fans: as a writer, he wanted readers to pay for books, so that he could earn a living.) Gee apologized for having “roused [his] ire,” but insisted all books not actively being read are “dead . . . Put on the shelf in both senses of the word.” As a compromise, she suggested pooling resources with other Forteans to build a lending library (something many science fiction fans did). She also included her dues and a clipping from the Paris edition of the New York Herald Tribune, something she hadn’t seen in the English newspapers. (Her reading papers from Paris and her last name both raise the possibility of Gee being French.)

Gee showed up in Doubt not long after—credited with a clipping about flying saucers in issue 23 (December 1949). Thayer acknowledged her in correspondence with Russell for the first time the next month. She continued to write to both Thayer and Russell and send in a load of clippings, all throughout the rest of the decade and into the 1950s. By my count, she was mentioned 67 times in Doubt, placing her with Mary Bonavia as one of the leading female contributors to the magazine, and a stalwart from which the magazine was built. She seemed very intent to connect with other Forteans. She met Leslie Shepard. She met J. T. Boulton. In Doubt 24 (April 1949), she advertised for Fortean correspondents (this after asking Russell for a list of members, and probably being rebuffed):

“Also, a member of the female persuasion, a (Mrs.) Judith L. Gee, 27a, Goldhurst Terrace, Hampstead, London, N.W. 6., England, writes ‘Do you think you could publish an appeal from me in DOUBT as a medium between members. After all such oddities as we are, are of interest to one another, and I for one would like to write to fellow members ,all [sic] over the world--but how can I, when there is no media of exchange. [sic]’

“Mrs. Gee would also like to meet London members face to face--if not eye to eye. She concludes: ‘My husband saw Charles Fort in Hyde Park and British Museum when he was in London, and he has spoken to another Hyde Parkean, who remembers him well. Why not send an expedition to contact these people while they still live.”

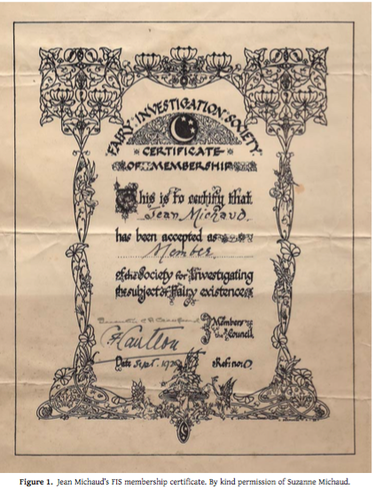

Her interest in Forteana and related subjects remained, apparently throughout her life. Soon after joining the Society, she bought from it a volume on Nostradamus. She wrote for Astrology: the Astrologer's Quarterly (1950). Leslie Shepard interviewed her for an article on cloud busting—that is controlling weather—that was published in 1955. She was quoted saying, "My method is simplicity itself. It is the non-acceptance of clouds and rain…. So when I want sun shine, I just see the sun shining … the clouds parting and dispersing and blue skies triumphant.” In 1957, she was a member of the Fairy Investigation Society. In the 1970s, she contributed letters to Fate magazine about a so-called UFO prophet, Ted Owens. She sometimes warranted her own column in Doubt, such as in Doubt 51 (January 1956), when Thayer compiled a number of her submissions under the title “Gee has a Field Day”: antibiotics causing cancer, a pearl in a hen’s egg, a reverend who attracted the following of birds and beasts, a wallaby loose in England. The whole gamut of Thayer’s Fortean topics.

But for all that, the correspondence between Thayer and Russell—admittedly, all from Thayer’s pen—was usual dismissive of her. Chibbett’s letter set the stage: Gee was considered too credulous even by other Forteans, and a bit annoying. Russell, apparently, did not both to save any of her letters. There’s only one more scrap in his archives—about the resurgence of Fascism—though it is clear she did continue to write both Russell and Thayer. It is hard to avoid the conclusion that Gee’s gender—remarked on these several times quoted above—played some role in how she was treated: an air-headed female. Elsender and Simpson, Brits with similarly esoteric tastes, received more positive affirmations (or at least silence) from Thayer and Russell than Gee.

Thus, in Thayer’s first letter about her, from January 1949, he tells Russell, “Gee writes in such a vein that the only thing I can do is ignore her.” It is not clear what this refers to exactly, but comes in a discussion of anti-Semitism, and so may be Thayer bristling about Gee’s views on the matter. (Both he and Russell were off-handed anti-Semites.) A year later, Thayer bitched to Russell that Gee didn’t do what as he said. He complained about her demands and her woo-woo: “Gee gets more astral all the time.” He joked that others with interests in the outer limits of Fortean thought must have been brought in by Gee. And they made light of her sex: “Gee reports that you are flirting with her. Are you trying to beat my time there?”

None of this is horrid. It’s the casual sexism of the day, amplified by the issues related to race and belief. It is striking, though, in the context. Gee was intensely interested in the Fortean Society and worked hard both for it and to knit together a Fortean community—as opposed to mere Society—in London. And she did have some faults; at least, characteristics that came through in the mail that could be annoying: her sense of entitlement and seeming belief that all right-thinking people shared her views. (Although, to be fair, Russell and Thayer shared these same faults.) But what she received was a lot of sniping behind her back, which seems unfair. It serves, too, in hiding her. Had Thayer or Russell been more engaged, writing her up in the magazine, as Thayer did with others, or keeping all of her correspondence, we would have known more about her. Instead, she became, herself, a damned fact.

“The post mark is Liverpool, but I am in doubt, whether I have to thank Mr. Chibbett, or the Forteans of New York for passing me on to you. Do please settle this doubt!

“Mr. Chibbett, who has been to see me, has mentioned your name as chief Fortean in England. But, I had written to New York for a copy of their magazine, that is why I question whom I have to thank.”

Although it cannot be stated definitively, the reason for Chibbett’s connection to Gee seems obvious in retrospect: they ran in the same circles. She had written to letters to the British “Occult Review,” unseen by me, which very may have led Chibbett to her. In a later letter to Thayer, Gee said that her husband had seen Charles Fort during his London years, and new others from the neighborhood who remembered him, suggesting an abiding interest in the anomalous. She was keen to continue connecting with the Society and Forteans more generally, asking Russell in her letter how to convert English moneys into $2 American and if he could lend her the entire earlier run of Doubt for an “indefinite period” so that she could “read them in digestible comfort.”

Russell seems to have written back fairly quickly, with a letter that does not survive, dunning her 10 shillings and telling her to see Atlantis Bookshop for back issues of Doubt. She replied on 13 August, thanking him, noting that she had received copies of Doubt from America (as well as other American magazines, which left her “up to my ears reading them, and growling at interrupters”), and inviting him to visit some time. She said that she knew the Atlantis Bookshop and its owner—Michael Houghton—quite well, but wasn’t sure she could afford to by any books at the time, and so was still anxious to borrow relevant tomes. She also wondered what had become of N.V. Dagg’s magazine “Tomorrow,” presumably asking because Russell was a frequent contributor. She had subscribed and enjoyed the periodical until it became blatantly anti-Semitic, at which time she dropped it and “suspect[ed] anything that comes from that stable.”

Again, Russell seems to have replied diligently, though perhaps less kindly—once more, the letter does not exist—apparently bristling at being called “chief Fortean” in England and taking issue with Gee’s interest in borrowing books. (Borrowing was a long-time bugaboo of Russell’s, and something he held against science fiction fans: as a writer, he wanted readers to pay for books, so that he could earn a living.) Gee apologized for having “roused [his] ire,” but insisted all books not actively being read are “dead . . . Put on the shelf in both senses of the word.” As a compromise, she suggested pooling resources with other Forteans to build a lending library (something many science fiction fans did). She also included her dues and a clipping from the Paris edition of the New York Herald Tribune, something she hadn’t seen in the English newspapers. (Her reading papers from Paris and her last name both raise the possibility of Gee being French.)

Gee showed up in Doubt not long after—credited with a clipping about flying saucers in issue 23 (December 1949). Thayer acknowledged her in correspondence with Russell for the first time the next month. She continued to write to both Thayer and Russell and send in a load of clippings, all throughout the rest of the decade and into the 1950s. By my count, she was mentioned 67 times in Doubt, placing her with Mary Bonavia as one of the leading female contributors to the magazine, and a stalwart from which the magazine was built. She seemed very intent to connect with other Forteans. She met Leslie Shepard. She met J. T. Boulton. In Doubt 24 (April 1949), she advertised for Fortean correspondents (this after asking Russell for a list of members, and probably being rebuffed):

“Also, a member of the female persuasion, a (Mrs.) Judith L. Gee, 27a, Goldhurst Terrace, Hampstead, London, N.W. 6., England, writes ‘Do you think you could publish an appeal from me in DOUBT as a medium between members. After all such oddities as we are, are of interest to one another, and I for one would like to write to fellow members ,all [sic] over the world--but how can I, when there is no media of exchange. [sic]’

“Mrs. Gee would also like to meet London members face to face--if not eye to eye. She concludes: ‘My husband saw Charles Fort in Hyde Park and British Museum when he was in London, and he has spoken to another Hyde Parkean, who remembers him well. Why not send an expedition to contact these people while they still live.”

Her interest in Forteana and related subjects remained, apparently throughout her life. Soon after joining the Society, she bought from it a volume on Nostradamus. She wrote for Astrology: the Astrologer's Quarterly (1950). Leslie Shepard interviewed her for an article on cloud busting—that is controlling weather—that was published in 1955. She was quoted saying, "My method is simplicity itself. It is the non-acceptance of clouds and rain…. So when I want sun shine, I just see the sun shining … the clouds parting and dispersing and blue skies triumphant.” In 1957, she was a member of the Fairy Investigation Society. In the 1970s, she contributed letters to Fate magazine about a so-called UFO prophet, Ted Owens. She sometimes warranted her own column in Doubt, such as in Doubt 51 (January 1956), when Thayer compiled a number of her submissions under the title “Gee has a Field Day”: antibiotics causing cancer, a pearl in a hen’s egg, a reverend who attracted the following of birds and beasts, a wallaby loose in England. The whole gamut of Thayer’s Fortean topics.

But for all that, the correspondence between Thayer and Russell—admittedly, all from Thayer’s pen—was usual dismissive of her. Chibbett’s letter set the stage: Gee was considered too credulous even by other Forteans, and a bit annoying. Russell, apparently, did not both to save any of her letters. There’s only one more scrap in his archives—about the resurgence of Fascism—though it is clear she did continue to write both Russell and Thayer. It is hard to avoid the conclusion that Gee’s gender—remarked on these several times quoted above—played some role in how she was treated: an air-headed female. Elsender and Simpson, Brits with similarly esoteric tastes, received more positive affirmations (or at least silence) from Thayer and Russell than Gee.

Thus, in Thayer’s first letter about her, from January 1949, he tells Russell, “Gee writes in such a vein that the only thing I can do is ignore her.” It is not clear what this refers to exactly, but comes in a discussion of anti-Semitism, and so may be Thayer bristling about Gee’s views on the matter. (Both he and Russell were off-handed anti-Semites.) A year later, Thayer bitched to Russell that Gee didn’t do what as he said. He complained about her demands and her woo-woo: “Gee gets more astral all the time.” He joked that others with interests in the outer limits of Fortean thought must have been brought in by Gee. And they made light of her sex: “Gee reports that you are flirting with her. Are you trying to beat my time there?”

None of this is horrid. It’s the casual sexism of the day, amplified by the issues related to race and belief. It is striking, though, in the context. Gee was intensely interested in the Fortean Society and worked hard both for it and to knit together a Fortean community—as opposed to mere Society—in London. And she did have some faults; at least, characteristics that came through in the mail that could be annoying: her sense of entitlement and seeming belief that all right-thinking people shared her views. (Although, to be fair, Russell and Thayer shared these same faults.) But what she received was a lot of sniping behind her back, which seems unfair. It serves, too, in hiding her. Had Thayer or Russell been more engaged, writing her up in the magazine, as Thayer did with others, or keeping all of her correspondence, we would have known more about her. Instead, she became, herself, a damned fact.