John Wood Campbell, Jr., was born 8 June 1910 in Newark, New Jersey to John W. Campbell and the former Dorothy Strahern. Raised in middle class material comfort—his father was an engineer—but great emotional turmoil, caught in the triangle between a distant father, an unpredictable mother, and a resentful aunt (his mother’s twin), Campbell turned to science and engineering: by accounts, he was reading astronomy and physics books as early as eight years old, and tinkering on bicycles. He would always appreciate scientists and engineers as cultural heroes, doing what needed to be done, changing and perfecting the human race. Campbell went to the private Blair Academy and did not do well, but got into MIT anyway.

He discovered science fiction in his teens. The genre was just beginning to take shape. There were scientific romances and adventure stories from older generations—Poe and Verne—as well as stories along those lines being produced by contemporary authors—Wells, Burroughs, Doyle—but it was Hugo Gernsback who was consolidating science fiction into a recognizable genre. His Amazing Stories came out in 1926. At MIT, Campbell wanted to buy a car, but his father refused, and so he turned to writing stories for the new science fiction market, and found himself successful enough. He finished MIT (did he?) but also continued writing under a couple of names.

His John W. Campbell byline went with stories of what he called, in a clever spoonerism, “thud and blunder,” tales of galactic derring-do and adventure. Under a pseudonym, Don A. Stuart, he worked out more thoughtful, though also deeply pessimistic, narratives. These often lacked a robust plot, but made of for it with their considerations of the limits of science and human knowledge. He also used the names Karl van Campen and Arthur McCann.

He discovered science fiction in his teens. The genre was just beginning to take shape. There were scientific romances and adventure stories from older generations—Poe and Verne—as well as stories along those lines being produced by contemporary authors—Wells, Burroughs, Doyle—but it was Hugo Gernsback who was consolidating science fiction into a recognizable genre. His Amazing Stories came out in 1926. At MIT, Campbell wanted to buy a car, but his father refused, and so he turned to writing stories for the new science fiction market, and found himself successful enough. He finished MIT (did he?) but also continued writing under a couple of names.

His John W. Campbell byline went with stories of what he called, in a clever spoonerism, “thud and blunder,” tales of galactic derring-do and adventure. Under a pseudonym, Don A. Stuart, he worked out more thoughtful, though also deeply pessimistic, narratives. These often lacked a robust plot, but made of for it with their considerations of the limits of science and human knowledge. He also used the names Karl van Campen and Arthur McCann.

Campbell married for the first time in 1931, his wife the former Dona Stewart (source of the pseudonym Don A Stuart). The next year, having left MIT, he went to Duke University, where he received a B.S. in physics. He had a number of small-time jobs for a couple of years, selling cars, heaters, and fans. He got his foot in the door at Street and Smith in 1937, when he was hired to assist with Astounding Stories.

In 1937, Campbell took over Street & Smith’s “Astounding Science Fiction,” and mostly quit writing fiction. The title had fallen on hard times under another publisher, and was revived by F. Orlin Tremaine, who introduced a number of techniques that helped to push science fiction into realm of ideas while also keeping it grounded. Tremaine prized what he called “thought-variants,” the careful working out of some set of premises in a story world; he also encouraged his others to use one only major premise—there exists magic, for example, or the existence of one type of alien—rather than a melange of weirdnesses that could overwhelm the reader and the story. (Tremaine also serialized Fort’s “Lo!”)

Campbell continued these tendencies, and also insisted, as best he could, on literary excellence, or at least competence. He wanted the stories to work as literature as well as thought-variants. For him, science fiction was at its best when dealing with what he called “universal principles.” He wanted the laws of science, even if they weren’t the laws as they were currently understood. Soon enough, he collected a stable of talented writers which is almost completely isomorphic with the so-called Golden Age of science fiction: Van Vogt and Heinlein and Asimov and DeCamp and Sturgeon and Clement and Russell and del Rey. Astounding became the standard bearer of science fiction: even those who resented Campbell and his magazine acknowledged its importance, even as they took potshots at them both. Campbell also edited, for a short time, a companion magazine “Unknown,” which sought to import his ideas about universal themes and the stringencies of “Astounding”—one single major premise allowed per story—into stories of fantasy. It was here that Eric Frank Russell’s most Fortean story, “Sinister Barrier,” first appeared.

Campbell continued as editor of “Astounding” for decades—until the early 1970s. He saw himself as a spider at the web-center of science fiction literature. He coaxed and cajoled stories from his writers, and was not above manipulating them, either, capriciously rejecting stories to prove his power, and then buying them after some edits. Campbell saw his writers as extensions of himself: he was writing the stories, working out the ideas through them. He was a boss and they were boys: though this measure failed in the ultimate test, when he pitted himself against Heinlein, too, and Heinlein ended up gaining the upper hand, the ability to write what he wanted when he wanted and about what he wanted, because he was that good.

Campbell’s marriage to Dona fell apart in the late 1940s, and they divorced in 1950. Campbell remarried soon after, his new wife the former Margaret ‘Peg’ Winter. They had four children together. By this point Campbell was spending as little time in his New York office as possible, editing from his home in Princeton, and writing a tremendous amount of correspondence. Also by this point, authors whom he had groomed were getting too big for Astounding, finding new markets—sometimes in the pulps, often in the burgeoning paperback field. Some of his ideas seemed old-fashioned, as he struggled, for example, to keep sex (and even the suggestion of sex) out of his stories.

Campbell’s “Astounding” remained the sine qua non of science fiction through the forties, though he found it difficult to get stories during the middle of the decade, when war work forced a number of his writers away from their typewriters. By mid-1950s there did come to be challengers, Horace Gold’s “Galaxy” and “Fantasy and Science Fiction” both putting out excellent stories—even as Gold and Anthony Boucher, co-editor of “F&SF” published in “Astounding.” And by the 1960s, even as “Astounding” continued to be the best-selling of the science fiction magazines, Campbell’s finger was no longer on the pulse of science fiction, its innovations now taking place elsewhere, the standard bearer no longer the standard of excellence.

Part of the reason for the decline may be that Campbell became too interested in off-trail subjects—that is to say, like Ray Palmer before him, Campbell blundered across the (very thin) line between legitimate scientific extrapolations, as understood by writers and a vocal contingent of fans, and occultist notions. Campbell had no truck with the Shaver mystery, but he bought into other ideas: he was a huge proponent of L. Ron Hubbard’s Dianetics—Hubbard had been a favored author—and ran articles on it, as well as becoming a functionary in its hierarchy and practicing auditing. (He understood his own divorce and remarriage in terms of Dianetics.)

He was interested in new “psi” sciences—what Fort called “Wild Talents”—and thought these could revolutionize science as it was known. But he did not think scientists necessarily needed to take up the subject—that was the job of gifted amateurs like him (and Hubbard): to do basic work, until scientists could take over. He was enough of a conspiracist to think that certain technologies were suppressed—he believed there really was a pill that could convert water to gasoline, but it was kept off the market by oil companies pricing gas lower than the pill would have cost, for example, and he was interested in something called a Dean Drive.

Campbell was, as an editor, long-winded in how he talked (and corresponded) with his authors; his magazines had featured regular editorials on whatever notion struck his fancy—presumably filling the gap left by having his fiction, as he saw it, now written by others. He liked to hear himself. And he liked to say it again and again, with new and different analogies. Toward the end of his life, this self-regard curdled from the generally progressive views he held in his earlier years—though always with more than a little elitism, sexism, and racism—into a fairly sou right wing annoyance at the world, presumably for not living up to his hopes. He supported George Wallace in 1968, for example.

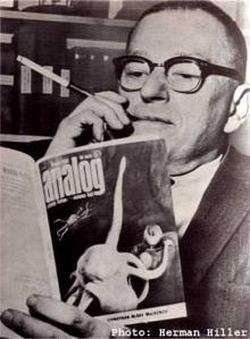

John Wood Campbell, Jr., died of heart failure—he had been a chain smoker throughout his life—11 July 1971. He was 61.

***********************

Campbell discussed Fort perhaps more than any other science fiction Fortean—with the exception of Eric Frank Russell—though there are significant gaps in knowledge about his acquaintance with Fort. When did he first read him, for example? I do not know. Certainly he read Astounding’s serialization of “Lo!” in 1934. But did he come across Fort before? And what did he think about Fort then? There’s some indication that he found Fort’s style intriguing—Fort could be “rollicking reading,” he said later and also some indication he was turned off by Fort’s attacks on science, though he also said this much later, and his views may have been colored by controversies then ongoing: “Fort did a lot of shin-kicking, too. When I first read his books, he kicked my shins, but good. . . . The method of salesmanship made me exceedingly disinterested in tasting the product.”

Based on the writings of his I have seen, Campbell had two interpretations of Fort, one from the early 1940s, and one from the early 1950s—after the introduction of Dianetics—and mostly just repeated these same views, in various forms. And, to be fair, the two views were not that different; rather, the context changed, and so he emphasized different points. However, over time, his views did increasingly become disconnected from Fort himself, and what Fort had written, and, instead, were descriptions of a Fort that he had reconstructed in his own mind.

It would be easy enough too dispense with Campbells Forteanism in a few paragraphs. But there is another way that he shaped Fortean thought, and that is through his editing. A number of his writers—to varying extents—adopted Fortean ideas, or worked them into stories at least, and these passed through Campbell’s editorial filters. Indeed, there’s a sense in which Astounding was one of the best examples of what Tiffany Thayer thought of as Fortean art. (It’s also true that Fort influenced more high brow, or avant-garde forms of art, too.) And so Campbell’s tête-à-têtes with authors shows how Fortean ideas made their way into science fiction, especially in light of Dianetics.

Campbell’s first reference to Fort—that I can find—came in a review of the collected books that ran in the August 1941 issue of “Astounding” magazine—dated about eight months after the omnibus Fort had been released; a slightly revised and shortened version of the review appeared in “Unknown” four more months on, in December.. The review showed Campbell to be a Fortean in the mold of Maynard Shipley: intrigued by the facts that Fort had collected, but unconvinced by his own theorizing, and even a little turned off by his anti-science (though Campbell was more empathetic than Shipley). As Campbell saw it, Fort had come of age—around the turn of the century—at a time when physicists, especially, were cocky, certain that there was only a bit more to figure out, and everything would be done, which explains Fort’s antagonism toward scientists and their arrogance.

Fort then collected a bunch of errors scientists had made, and a whole mass of facts that could not be accounted for by accepted scientific theories. He assembled these into his own set of theories. Campbell had no time for Fort’s anti-science—scientists were more accepting of their own limitations now—and even less for Fort’s vague theorizing—“his suggested pattern doesn’t make satisfactory sense,” he said. No, what appealed to Campbell—and had appealed to Shipley—were all those facts: Fort’s important work was on collecting in one place the mass of the still unco-ordinated [sic], normally observed facts of nature.” Eventually, he thought, worked on by the right minds, these facts could be turned into real science: “If only we could find the pattern hidden there among the vast jumble of facts—it probably contains the root truths of about four new sciences.”

In the meantime, here was a source book for science fictioneers. (Supposedly, Tremaine had originally bought rights to “Lo!” so that he could farm out ideas to his writers.) Campbell wrote, “It probably averages one science-fiction or fantasy plot idea to the page.” So, more than one-thousand ideas. Campbell’s ideas about how to write science, and his championing of Fort as a source, was congruent with Thayer’s ideas about Fortean art: the idea was to take unusual premises and work them out. Thayer had the notion of writing symphonies in weird keys or designing art according to unusual ratios; Campbell wanted his writers to work out scientific laws even if those laws were not as currently understood. No wonder, then, that Thayer would highlight science fiction as the par excellence example of Fortean art, even as he admitted dissatisfaction at it being so limited.

As indicated above, though, this review was certainly not Campbell’s first encounter with Fort. Earlier in the 1930s, for example, he had battled with Heinlein over certain Fortean notions, and their appearance in the magazine. One of Heinlein’s first stories was “Lost Legacy,” which mixed occultish notions about “wild talents” with speculations on the disappearance of Ambrose Bierce, among others (which disappearance had been featured by Fort.) Campbell rejected the story; in Alexei Panshin’s view, Campbell thought it too flabby: Heinlein was not working out universal principles. Heinlein got the story published elsewhere, but struggled for a time to find the right voice, the one that Campbell would like and that still allowed him to play with Fortean notions about wild talents and real truths beyond known science. Eventually he did, and, as Panshin has it, the balance of power between Campbell and Heinlein slowly tilted in Heinlein’s favor: he won the right to write about what he wanted on his own schedule, and Campbell was so desperate for his stories that he conceded.

Even so, Campbell tested that power imbalance, and the immediate fight was over perhaps Heinlein’s most Fortean story, “Goldfish Bowl.” Campbell rejected it. The story, like Russell’s Sinister Barrier, took seriously Fort’s notion that humans may be property, owned by intelligences so vast as to be almost inexplicable to human minds. Heinlein responded a couple of times in the late summer of 1941 about the time Campbell’s review of Fort appeared in “Astounding,” Heinlein’s second letter responding to the rejection said, in part:

“This particular story was intended to give an entirely fresh angle on the invasion-by-alien-intelligence theme. So far as I know, every such story has alien intelligences which treat humans as approximate equals, either as friends or as foes. It is assumed that A-I will either be friends, anxious to communicate and trade, or enemies who will fight and kill, or possibly enslave, the human race. There is another and much more humiliating possibility—alien intelligences so superior to us and so indifferent to us as to be almost unaware of us. They do not even covet the surface of the planet where we live—they live in the stratosphere. We do not know whether they evolved here or elsewhere—will never know. Our mightiest engineering structures they regard as we regard coral formations, i.e., seldom noticed and considered of no importance. We aren't even nuisances to them. And they are no threat to us, except that their "engineering" might occasionally disturb our habitat, as the grading done for a highway disturbs gopher holes.

“Some few of them might study us casually—or might not. Some odd duck among them might keep a few of us as pets. That was what happened to my hero. He got too nosy around one of their activities, was captured, and by pure luck was kept as a pet instead of being stepped on. In time he understood his predicament, except in one respect—he never did realize to its full bitterness that the human race could not even fight these creatures. He was simply a goldfish in a bowl—who cares about the opinions of a helpless goldfish? I have a fish pond in my patio. Perhaps those fish hate me bitterly and have sworn to destroy me. I won't even suspect it—I'll lose no sleep over it. And it seems to me that the most esoteric knowledge of science would not enable those fish to harm me. I am indifferent to them and invulnerable.”

With Heinlein seemingly content to stop sending in stories after the rejection, Campbell eventually relented, and the story appeared.

Fortean inflected stories continued to appear through the 1940s, including some by authors, such as Isaac Asimov, who didn’t otherwise seem to have much truck with Fort or Forteanism. Science fiction critic Sam Moskowitz wrote, “The review by John W. Campbell of The Books of Charles Fort in the August 1941 Astounding Science Fiction most heartily recommends it as a source book for plots. This advice was not only followed by his authors but in some cases was urged upon them by Campbell. At first the adaptations were subtle and of the same high order of originality as "The Space Visitors" and "The Earth Owners". A prime example was "The Children's Hour" by C.L. Moore writing under the pen name of Lawrence O'Donnell (Astounding, March 1944). . . . However, the trend was to take a different turn as evidenced in Robert A. Heinlein's "Waldo" (Astounding, August 1942), where a rocket drive is repaired and operates by witchcraft!”

The next flare up over Forteanism in the magazine of which I am aware came in the early 1950s, and involved a number of Campbell’s authors. This was at the time that Campbell was becoming increasingly interested in Dianetics, which shaped his interpretation of Fort, as well as “psionics,” which also effected his interpretation, and when the magazine was no longer on the cutting edge of the genre but was being pressed by other magazines and paperbacks, his authors expanding beyond the small but robust confines he had created. At the time, Campbell was farming out lots of ideas to his authors on psionic and dianetic topics, and some were responding positively.

In July 1950, he wrote to Eric Frank Russell suggesting a story that combined dianetics and Fort in such a way that repudiated Heinlein’s “Goldfish Bowl”—it was more along the lines of aliens as space brothers, in fact. “Fort said, ‘We’re property.’ Fort was wrong,” he began, arguing that humans are not property but children, “the dearly beloved bratlings.” And he imagined a time when the aliens that oversaw human development were forced, by some circumstance in the universe, to call on the help of humans—humans whose “basic personality,” as it was called in Dianetics, though essentially good, had been scarred by their intergalactic parents. What would happen to the relationship between the parents—which he noted were also coded versions of the Holy Trinity—and their earthling children after the crisis was overcome?

Russell did not take up the idea, nor did he take up another idea that Campbell was then shopping—what if there was a technology that could essentially offer you immortality for the cost of giving up all of your irrational prejudices (an idea clearly extrapolated from Dianetic auditing)? But Campbell’s letter sketched in some battle lines between the two over the meaning of Charles Fort. The matter was mostly quiescent for the next couple of years, even as Campbell admitted to Russell that he was interested in Fortean topics such as teleportation, telepathy, and levitation. He just did not know that those subjects were ready to be attacked by scientists, since they were so far from the known forces of nature—bridges needed to be built from the known to the unknown, and the distance was too far. Still, he had authors working on the idea: Isaac Asimov published “Belief” in “Astounding”’s August 1953 issue, and Mark Clifton and Alex Apostolides published ‘What Thin Partitions’ in the September issue. Sam Moskowitz called the latter “by far the most masterful story ever written concerning levitation.”

By April 1952, niggling disagreements between Russell and Campbell—on Fort, but especially on the topic of Dianetics, which Russell saw as hogwash, dismissing the end goal of becoming sane (or clear) as ridiculous—had accumulated enough that Campbell had to address the matter. (Russell’s letters to Campbell no longer exist, as far as I know.) Campbell wrote,

“Generally, we’re in agreement on most of the aspects we’ve touched on; I might say that our disagreement over the value of Fort’s work is, perhaps, typical of what disagreements we have. I hold that Fort’s work was definitely ‘con’ data—confusing. Fort collected data as a pack-rat collects stuff. There is no selectivity; his information is not digested [sic], or integrated. Throwing a mass of undigested data at people is an old habit of our culture—and a stinking bad one, too. Data is absolutely useless until it is organized. The multiplication tables are data; they’re absolutely useless for anything but doing multiplication—and until you learn to see that real problems in real life require multiplication, the tables are undigested and undesired data. What problem does this data refer to and help to solve?

“Fort was angry that science did not accept his data, and immediately use it. So Fort damned science, and damned all the data science had! He was guilty in far greater degree that science [sic]; he didn’t digest the data of science, he simply rejected it in toto. The organization he made of his data is, therefore, utterly useless, because it doesn’t tie in with the actual data of science. Fort was a Mystic; he said, in essence, reject all there ideas, and see the importance of mine!

“I’ve never rejected the data—I’ve just questioned it most ferociously, because Fort was such a thuroughly [sic] unstable, unreasonable, unselective, and unintegrated personality that I couldn’t trust his data.

“Newspaper clippings are not reliable, per se; they can be used only when there are multiple reports oft he same event, continued over a period of time.

“Look, the mystics have been saying for millenia [sic] ‘All is illusion; the physical works is illusion without substance.’

“today, the physical scientist is saying ‘All mater is illusion; the physical world is illusion without substance.’

“They are, then, in complete agreement? By no means! The mystic says “This I know within me; it is not something that can be questioned and argued. It must be understood by faith and belief, and cannot be explained.’

“The physicist says, ‘This we know by studying the nature of matter; we find that it is actually composed of electric, magnetic and other force fields, which have the following characteristics . . . . . . The reason it appears to be solid is as follows . . . . . .’

“The mystic, down the ages, has been charachterized [sic] by the inability to communicate his findings; Jesus could walk on water, but his own disciple, in his presence, couldn’t do it. Jesus had powers which he was totally unable to communicate, although he could use them.

“Mysticism failed because it didn’t learn how to teach. It could do, but not explain or teach. Physical science hasn’t been able to do a lot of things mysticism did—but it can do something a lot more important. Every gain that physical science has made, it has been able to communicate fully. It’s not adequate for human beings to simply know-thin; they must be able to explain-without if the race as a whole is to benefit.

“It must not be communication at a subliminal level, either; emotional feeling is not adequate communication. There mist be communication at the verbalized, conscious level.

“The problem is, essentially, to develop a communication technique that can communicate all human experience. When the mystic makes contact with the Essence of God, he must be able to communicate the understanding achieved in such a fashion that other human beings actually succeed in doing the same. The root essence of physical science is that anyone can learn it, and practice it. It’s communicable knowledge-understanding.”

Nominally, this was about Fort, but it was really about Hubbard and Dianetics. Campbell was becoming irritated by Hubbard’s approach. In a letter written the next month, Campbell said,

“Eric. my intention is to bring attention to the existance [sic] pf phenomona [sic] outside the range of existant [sic] physical science. I deeply want to attract the attention of physical scientist [sic], whom I respect for good and sufficient reason (they’ve produced results in making things actually work) to problems of the real world that I feel are acute and important.

“Fort and I are, in other words, in full agreement on the goal. Hubbard and I were in full agreement on the goal. But Hubbard I now recognize made the same error Fort did—and for the same reason, I suspect.

“Any human being wants to feel that he has real existance [sic], and the only way to detect the reality of your existance [sic] is by effecting the world around you. A ghost would feel horribly unreal . . . “ goes on to say attacks on science were a way of feeling real. leaves fort behind and concentrates on hubbard. then: “Fort did a lot of shin-kicking, too. When I first read his books, he kicked my shins, but good. He was trying to sell me doughnuts for breakfast, and the method of salesmanship made me exceedingly disinterested in tasting the product.

“He didn’t bother to find out why physical scientists wouldn’t accept his ideas; had he done so, he could have found out what to do about it.”

Now, it may be that Campbell wanted science to take these matter seriously; and it may even be that Hubbard did, too, though this is less clear. But Fort was never really interested in getting science to take up his ideas and absorb them: he did not want his fact to become part of science; he was trying to transcend science. It was a so-called Dominant—what could also be called an era—that was being left behind. Campbell continued to voice this same objection to Fort over the next several years, though it became increasingly untethered from Fort—it’s not clear that Campbell had re-read Fort in more than a decade—and a way of talking about his frustrations with Hubbard, especially, but others interested in fringe scientific ideas: that they were not doing what was necessary to have their ideas taken seriously.

He wrote in October 1952, “Fort was insisting that someone else do the work of integrating them, and refusing to organize and interpret the data into intelligible stuff himself. For that, Fort should have been shown the door. He was too lazy to do the hard work; he wanted it done for him, and was very petulant because no one would. It was too damned much of a case of ‘Let’s you and him have a fight, huh?’

His data was valid. It contained important understandings, and important clues. In that, he was right. But why didn’t _he_ do some of the hard work of integrating it and finding the pattern, instead of frothing about how everyone else wouldn’t do that work?” As an example, he pointed out in May, “If he believed in the validity of poltergeist, why didn't he, personally, make a good, hard try at getting some understanding of what could be done to produce the phenom—-[sic] instead of shrieking that it must be done?

“Collecting data as he did is the smallest and least step of a job of research; the biggest and most important job is sifting data to determine which ones are critical, which ones are clues pointing the way to a solution.”

Instead, Fort only debunked—he destroyed without building, Campbell said, which wasn’t exactly true—Fort did have a vision of the future, it just wasn’t one in which all knowledge was subsumed by science. Campbell could not see that, though: science was, for him, still the ultimate arbiter of what counted as true—it was just slow in building up theories around facts, necessarily so. And for Campbell, Fort obviously wanted the approval of scientists—or, more accurately, Hubbard did: Fort “deeply wanted the attention of physical scientists, whom he actually respected somewhat unduly, to problems of the real world he recognized as being acute and important,” Campbell said in May 1952, and “Fort wouldn’t have been so violently insistant [sic] on attracting their attention if he hadn’t recognized, deeply, the high competence of the scientific method. Why didn’t he try, instead, to get theologians to study his data? Or mediums? The occultists and mystics would have listened to him gladly! Why, of all groups, did he belabor the physical scientists?”—which reads not like an interpretation of Fort, but like an extension of an argument he’d been having with Hubbard.

The matter was so important to Campbell because he thought that, through his science fiction magazine, he was laying the groundwork for this new science—creating the conditions for a better world. Russell did not develop Campbell’s idea about a machine that granted immortality for the cost of a person’s irrationalities, but Mark Clifton did (and his short stories became the basis for a novel). After Russell said something negative about Clifton’s work—the exact remark is unknown—Campbell responded in October 1952, “I’m trying to introduce the proposition of sciences beyond those currently known and accepted. But Eric PLEASE believe me; Charles Fort made a mistake. The error was his. He _insisted_ that the scientists understand him when he explained it all to them in Swahili. He even repeated it in Hindustani, and still the dolts wouldn’t listen to him. The one thing he didn’t try was to explain it in their stupid old language; it was obviously up to them to learn _his_ language, because he had something important to say.”

This was a manipulative strategy, he admitted, getting humankind to take its medicine with sugar—but take it no matter what. He told science fiction writer and editor Paul Anderson (who had published Heinlein’s “Lost Legacy”): “I’ve got Ray Jones and E.F. Russell and Isaac Asimov and Chad Oliver working on different aspects of it. We are, in essence, trying to teach the most thoughtful, speculative and philosophical group of Mankind--the science-fiction readership--a quite new viewpoint. It isn’t something they know they want to learn; therefore we have to do it by entertaining them enough so that they’ll accept the new ideas for the _sake of entertainment_, rather than for the _sake of the idea_.

But actually, in the long run, it makes little difference why they originally accept the idea--for fun, or for serious education; in either case the idea has been entered, and thought about, and will have an effect on the individual’s total philosophy. I drink orange juice in the morning because it tastes clean and sweet and fresh--because it makes my mouth feel good. I don’t drink it because my system needs glucose after the night fast, and because my system needs the organic acid to maintain the pH buffering effects, nor because ascorbic acid is vital to my nerve-system metabolism. What difference? I drink sugar and citric and ascorbic acids; I didn’t know I wanted them, but they make me feel good.”

The eat-your-spinach mentality was an adult one, Campbell thought—this went back to his story about aliens and human children that he offered to Russell: humanity was on the brink of adulthood, if it could move on to understand these unseen, unknown forces and master them. Ultimately, that was Fort’s problem—he remained scarred by a childhood event, and no doubt would have benefitted from some auditing, if only he had lived long enough: “I have a hunch that Fort was scared blue with pink polka-dots of getting anywhere near those forces; he probably contacted some of it accidentally during early childhood, got smacked down by it, and wouldn’t ever go near it again himself. Those forces lie beneath the sub-nuclear particles; uranium fission is a gentle release of a side-swipe of a minor readjustment of those forces. Get careless, or frisky with them, and you’ll get your come-_way_-uppance.” Fear kept Fort from exploring the workings of the anomalies he had identified.

There is a family resemblance between Campbell’s views from the 1940s and his views from the 1950s: in both cases he thought Fort could be a wellspring of science fiction and of science. By the 1950s, though, he was irritated with Fort for not doing more to get scientists to acknowledge his data and work with it—an irritation that was not voiced in the 1940s, as far as I know, and probably had more to do with Campbell’s own frustrations getting scientists to understand his ideas about new sciences. So he was tempting them, both by trying to work out enough science to his ideas to show them plausible and by tricking them by making the ideas intriguing: drink the orange juice because it’s good for you . . . and because it’s tasty.

The latter view of Fort, as inadequately addressing his ideas to science, seems to have solidified into Campbell’s primary idea about Forteanism. In the mid-1950s, Russell wrote a book on Fortean phenomena—“Great World Mysteries”—and tried to place parts of it as articles in Astounding. Campbell was not too pleased with the ideas—one was on the Marie Celeste, which he thought was overdone—nor Russell’s approach to Forteanism, which he thought hagiographic rather than scientific: “Are you interested primarily in validating Charles Fort, the individual—-or the reality of the great problem Fort wanted attacked?” He also did not like what he took to be Fort’s scolding of scientists, though he admitted Russell was much more reasonable: “Fort was an ill-tempered, impatient, and stupid man . . If you were the first in the field, and didn’t have the sour memory of Fort and his offensive tactics standing always in your way, the way you approach the mysteries would make them challenging, interesting, and would inspire work on them. If you don’t agree with that general idea . . . . why don’t you act the way Fort did?”

Campbell was interested in what Russell had to say about levitation—though he knew that subject would not be explored by scientists for a long time. But, as far as I know, Russell did not get an article on levitation into “Astounding.” A few parts of his book did appear in the magazine “Fantastic” And he did get an article on the medium Eusapia Palladino, a long-time subject of Fortean speculation, into “Astounding.” By this point, the correspondence between the two men had declined quite a bit, and Russell had drifted somewhat from Forteanism, if not Fort, as though writing the book had quieted that part of his mind.

Russell was surprised, it almost seems, by the amount of emotion he felt when Tiffany Thayer passed, in August 1959, as he admitted to Campbell. Campbell responded in his own way, empathetic, though also cool, analytical: “I had, of course, heard of Tiffany Thayer’s death; it happens I never had any real contact with him—-only through his interests did I know him. . . The depression you felt over Thayers’ death [sic] was, I suspect . . . The deep and heavy feeling of ‘Who, now, is left to carry on…?’ . . .

“Thayer may have done a lot to carry on the effects of Fort’s work, for instance, but he was in no sense a replacement for Fort—-and there never will be a replacement for” either of them.”

It was almost an apology, of sorts, to Fort, as well—since in earlier correspondence Campbell had insisted that Fort would be forgotten: he was no better than all the other mystics, having had an experience, but never bothering to explain it scientifically, and so of no use to future scientists or historians of science. Here Campbell was offering that Fort belonged to the elite, to the irreplaceable.

And, indeed, for all the irritation Campbell had about Fort, it’s clear that annoyance sprang, in part, from affection: both were involved int he same project, but Campbell thought Fort had done it wrong, and set back the movement. By the late 1950s, though, on some level, Campbell had to be coming to terms with the fact that he was also not going to revolutionize science on his own. Look at what had happened to Dianetics over the previous decade!

So it is fitting, in a way, what happened a year before Thayer’s death, in 1958.

Back in 1931, when the Fortean Society was first organized, Fort wanted no part of it—but was willing to join a group if it was called the “Interplanetary Exploration Society. After all, according to his cosmology—which he didn’t believe!—the other planets were only a few hundreds of miles away, so reachable given a change in perspective. Why not, then, a Society dedicated to traveling to them? Of course, such a Society was not founded.

Twenty seven years later, Campbell had an idea. It was an extension of his hope to have amateurs contribute to science by doing the dirty work—the work he thought Fort had refused to do—the dirty work of making fringe sciences respectable enough that genuine scientists would the take up the problems. It was, as well, a twist on an old idea by the science fiction writer Ray Cummings, what he called the Gentleman’s Scientific Association. Campbell thought there should be a journal to go with it, and he organized a few meetings, as well as—at the very least—a New England chapter, that included his writer Hal Clement.

Campbell chose the group’s name because, he wrote, “the very fact of the present reality of off-this-world vehicles helps to establish in a general audience the fact that speculative thinking does, and has, paid off.” He was thinking of rockets, and how science-fictioneers had promoted them long before scientists took rocketry seriously. They were a way to reach distant planets quickly—his cosmology was more expansive than Fort’s, but technology would annihilate distance in space, just as it had on earth. And so the name was the same: Campbell called it the “Interplanetary Exploration Society.”

In 1937, Campbell took over Street & Smith’s “Astounding Science Fiction,” and mostly quit writing fiction. The title had fallen on hard times under another publisher, and was revived by F. Orlin Tremaine, who introduced a number of techniques that helped to push science fiction into realm of ideas while also keeping it grounded. Tremaine prized what he called “thought-variants,” the careful working out of some set of premises in a story world; he also encouraged his others to use one only major premise—there exists magic, for example, or the existence of one type of alien—rather than a melange of weirdnesses that could overwhelm the reader and the story. (Tremaine also serialized Fort’s “Lo!”)

Campbell continued these tendencies, and also insisted, as best he could, on literary excellence, or at least competence. He wanted the stories to work as literature as well as thought-variants. For him, science fiction was at its best when dealing with what he called “universal principles.” He wanted the laws of science, even if they weren’t the laws as they were currently understood. Soon enough, he collected a stable of talented writers which is almost completely isomorphic with the so-called Golden Age of science fiction: Van Vogt and Heinlein and Asimov and DeCamp and Sturgeon and Clement and Russell and del Rey. Astounding became the standard bearer of science fiction: even those who resented Campbell and his magazine acknowledged its importance, even as they took potshots at them both. Campbell also edited, for a short time, a companion magazine “Unknown,” which sought to import his ideas about universal themes and the stringencies of “Astounding”—one single major premise allowed per story—into stories of fantasy. It was here that Eric Frank Russell’s most Fortean story, “Sinister Barrier,” first appeared.

Campbell continued as editor of “Astounding” for decades—until the early 1970s. He saw himself as a spider at the web-center of science fiction literature. He coaxed and cajoled stories from his writers, and was not above manipulating them, either, capriciously rejecting stories to prove his power, and then buying them after some edits. Campbell saw his writers as extensions of himself: he was writing the stories, working out the ideas through them. He was a boss and they were boys: though this measure failed in the ultimate test, when he pitted himself against Heinlein, too, and Heinlein ended up gaining the upper hand, the ability to write what he wanted when he wanted and about what he wanted, because he was that good.

Campbell’s marriage to Dona fell apart in the late 1940s, and they divorced in 1950. Campbell remarried soon after, his new wife the former Margaret ‘Peg’ Winter. They had four children together. By this point Campbell was spending as little time in his New York office as possible, editing from his home in Princeton, and writing a tremendous amount of correspondence. Also by this point, authors whom he had groomed were getting too big for Astounding, finding new markets—sometimes in the pulps, often in the burgeoning paperback field. Some of his ideas seemed old-fashioned, as he struggled, for example, to keep sex (and even the suggestion of sex) out of his stories.

Campbell’s “Astounding” remained the sine qua non of science fiction through the forties, though he found it difficult to get stories during the middle of the decade, when war work forced a number of his writers away from their typewriters. By mid-1950s there did come to be challengers, Horace Gold’s “Galaxy” and “Fantasy and Science Fiction” both putting out excellent stories—even as Gold and Anthony Boucher, co-editor of “F&SF” published in “Astounding.” And by the 1960s, even as “Astounding” continued to be the best-selling of the science fiction magazines, Campbell’s finger was no longer on the pulse of science fiction, its innovations now taking place elsewhere, the standard bearer no longer the standard of excellence.

Part of the reason for the decline may be that Campbell became too interested in off-trail subjects—that is to say, like Ray Palmer before him, Campbell blundered across the (very thin) line between legitimate scientific extrapolations, as understood by writers and a vocal contingent of fans, and occultist notions. Campbell had no truck with the Shaver mystery, but he bought into other ideas: he was a huge proponent of L. Ron Hubbard’s Dianetics—Hubbard had been a favored author—and ran articles on it, as well as becoming a functionary in its hierarchy and practicing auditing. (He understood his own divorce and remarriage in terms of Dianetics.)

He was interested in new “psi” sciences—what Fort called “Wild Talents”—and thought these could revolutionize science as it was known. But he did not think scientists necessarily needed to take up the subject—that was the job of gifted amateurs like him (and Hubbard): to do basic work, until scientists could take over. He was enough of a conspiracist to think that certain technologies were suppressed—he believed there really was a pill that could convert water to gasoline, but it was kept off the market by oil companies pricing gas lower than the pill would have cost, for example, and he was interested in something called a Dean Drive.

Campbell was, as an editor, long-winded in how he talked (and corresponded) with his authors; his magazines had featured regular editorials on whatever notion struck his fancy—presumably filling the gap left by having his fiction, as he saw it, now written by others. He liked to hear himself. And he liked to say it again and again, with new and different analogies. Toward the end of his life, this self-regard curdled from the generally progressive views he held in his earlier years—though always with more than a little elitism, sexism, and racism—into a fairly sou right wing annoyance at the world, presumably for not living up to his hopes. He supported George Wallace in 1968, for example.

John Wood Campbell, Jr., died of heart failure—he had been a chain smoker throughout his life—11 July 1971. He was 61.

***********************

Campbell discussed Fort perhaps more than any other science fiction Fortean—with the exception of Eric Frank Russell—though there are significant gaps in knowledge about his acquaintance with Fort. When did he first read him, for example? I do not know. Certainly he read Astounding’s serialization of “Lo!” in 1934. But did he come across Fort before? And what did he think about Fort then? There’s some indication that he found Fort’s style intriguing—Fort could be “rollicking reading,” he said later and also some indication he was turned off by Fort’s attacks on science, though he also said this much later, and his views may have been colored by controversies then ongoing: “Fort did a lot of shin-kicking, too. When I first read his books, he kicked my shins, but good. . . . The method of salesmanship made me exceedingly disinterested in tasting the product.”

Based on the writings of his I have seen, Campbell had two interpretations of Fort, one from the early 1940s, and one from the early 1950s—after the introduction of Dianetics—and mostly just repeated these same views, in various forms. And, to be fair, the two views were not that different; rather, the context changed, and so he emphasized different points. However, over time, his views did increasingly become disconnected from Fort himself, and what Fort had written, and, instead, were descriptions of a Fort that he had reconstructed in his own mind.

It would be easy enough too dispense with Campbells Forteanism in a few paragraphs. But there is another way that he shaped Fortean thought, and that is through his editing. A number of his writers—to varying extents—adopted Fortean ideas, or worked them into stories at least, and these passed through Campbell’s editorial filters. Indeed, there’s a sense in which Astounding was one of the best examples of what Tiffany Thayer thought of as Fortean art. (It’s also true that Fort influenced more high brow, or avant-garde forms of art, too.) And so Campbell’s tête-à-têtes with authors shows how Fortean ideas made their way into science fiction, especially in light of Dianetics.

Campbell’s first reference to Fort—that I can find—came in a review of the collected books that ran in the August 1941 issue of “Astounding” magazine—dated about eight months after the omnibus Fort had been released; a slightly revised and shortened version of the review appeared in “Unknown” four more months on, in December.. The review showed Campbell to be a Fortean in the mold of Maynard Shipley: intrigued by the facts that Fort had collected, but unconvinced by his own theorizing, and even a little turned off by his anti-science (though Campbell was more empathetic than Shipley). As Campbell saw it, Fort had come of age—around the turn of the century—at a time when physicists, especially, were cocky, certain that there was only a bit more to figure out, and everything would be done, which explains Fort’s antagonism toward scientists and their arrogance.

Fort then collected a bunch of errors scientists had made, and a whole mass of facts that could not be accounted for by accepted scientific theories. He assembled these into his own set of theories. Campbell had no time for Fort’s anti-science—scientists were more accepting of their own limitations now—and even less for Fort’s vague theorizing—“his suggested pattern doesn’t make satisfactory sense,” he said. No, what appealed to Campbell—and had appealed to Shipley—were all those facts: Fort’s important work was on collecting in one place the mass of the still unco-ordinated [sic], normally observed facts of nature.” Eventually, he thought, worked on by the right minds, these facts could be turned into real science: “If only we could find the pattern hidden there among the vast jumble of facts—it probably contains the root truths of about four new sciences.”

In the meantime, here was a source book for science fictioneers. (Supposedly, Tremaine had originally bought rights to “Lo!” so that he could farm out ideas to his writers.) Campbell wrote, “It probably averages one science-fiction or fantasy plot idea to the page.” So, more than one-thousand ideas. Campbell’s ideas about how to write science, and his championing of Fort as a source, was congruent with Thayer’s ideas about Fortean art: the idea was to take unusual premises and work them out. Thayer had the notion of writing symphonies in weird keys or designing art according to unusual ratios; Campbell wanted his writers to work out scientific laws even if those laws were not as currently understood. No wonder, then, that Thayer would highlight science fiction as the par excellence example of Fortean art, even as he admitted dissatisfaction at it being so limited.

As indicated above, though, this review was certainly not Campbell’s first encounter with Fort. Earlier in the 1930s, for example, he had battled with Heinlein over certain Fortean notions, and their appearance in the magazine. One of Heinlein’s first stories was “Lost Legacy,” which mixed occultish notions about “wild talents” with speculations on the disappearance of Ambrose Bierce, among others (which disappearance had been featured by Fort.) Campbell rejected the story; in Alexei Panshin’s view, Campbell thought it too flabby: Heinlein was not working out universal principles. Heinlein got the story published elsewhere, but struggled for a time to find the right voice, the one that Campbell would like and that still allowed him to play with Fortean notions about wild talents and real truths beyond known science. Eventually he did, and, as Panshin has it, the balance of power between Campbell and Heinlein slowly tilted in Heinlein’s favor: he won the right to write about what he wanted on his own schedule, and Campbell was so desperate for his stories that he conceded.

Even so, Campbell tested that power imbalance, and the immediate fight was over perhaps Heinlein’s most Fortean story, “Goldfish Bowl.” Campbell rejected it. The story, like Russell’s Sinister Barrier, took seriously Fort’s notion that humans may be property, owned by intelligences so vast as to be almost inexplicable to human minds. Heinlein responded a couple of times in the late summer of 1941 about the time Campbell’s review of Fort appeared in “Astounding,” Heinlein’s second letter responding to the rejection said, in part:

“This particular story was intended to give an entirely fresh angle on the invasion-by-alien-intelligence theme. So far as I know, every such story has alien intelligences which treat humans as approximate equals, either as friends or as foes. It is assumed that A-I will either be friends, anxious to communicate and trade, or enemies who will fight and kill, or possibly enslave, the human race. There is another and much more humiliating possibility—alien intelligences so superior to us and so indifferent to us as to be almost unaware of us. They do not even covet the surface of the planet where we live—they live in the stratosphere. We do not know whether they evolved here or elsewhere—will never know. Our mightiest engineering structures they regard as we regard coral formations, i.e., seldom noticed and considered of no importance. We aren't even nuisances to them. And they are no threat to us, except that their "engineering" might occasionally disturb our habitat, as the grading done for a highway disturbs gopher holes.

“Some few of them might study us casually—or might not. Some odd duck among them might keep a few of us as pets. That was what happened to my hero. He got too nosy around one of their activities, was captured, and by pure luck was kept as a pet instead of being stepped on. In time he understood his predicament, except in one respect—he never did realize to its full bitterness that the human race could not even fight these creatures. He was simply a goldfish in a bowl—who cares about the opinions of a helpless goldfish? I have a fish pond in my patio. Perhaps those fish hate me bitterly and have sworn to destroy me. I won't even suspect it—I'll lose no sleep over it. And it seems to me that the most esoteric knowledge of science would not enable those fish to harm me. I am indifferent to them and invulnerable.”

With Heinlein seemingly content to stop sending in stories after the rejection, Campbell eventually relented, and the story appeared.

Fortean inflected stories continued to appear through the 1940s, including some by authors, such as Isaac Asimov, who didn’t otherwise seem to have much truck with Fort or Forteanism. Science fiction critic Sam Moskowitz wrote, “The review by John W. Campbell of The Books of Charles Fort in the August 1941 Astounding Science Fiction most heartily recommends it as a source book for plots. This advice was not only followed by his authors but in some cases was urged upon them by Campbell. At first the adaptations were subtle and of the same high order of originality as "The Space Visitors" and "The Earth Owners". A prime example was "The Children's Hour" by C.L. Moore writing under the pen name of Lawrence O'Donnell (Astounding, March 1944). . . . However, the trend was to take a different turn as evidenced in Robert A. Heinlein's "Waldo" (Astounding, August 1942), where a rocket drive is repaired and operates by witchcraft!”

The next flare up over Forteanism in the magazine of which I am aware came in the early 1950s, and involved a number of Campbell’s authors. This was at the time that Campbell was becoming increasingly interested in Dianetics, which shaped his interpretation of Fort, as well as “psionics,” which also effected his interpretation, and when the magazine was no longer on the cutting edge of the genre but was being pressed by other magazines and paperbacks, his authors expanding beyond the small but robust confines he had created. At the time, Campbell was farming out lots of ideas to his authors on psionic and dianetic topics, and some were responding positively.

In July 1950, he wrote to Eric Frank Russell suggesting a story that combined dianetics and Fort in such a way that repudiated Heinlein’s “Goldfish Bowl”—it was more along the lines of aliens as space brothers, in fact. “Fort said, ‘We’re property.’ Fort was wrong,” he began, arguing that humans are not property but children, “the dearly beloved bratlings.” And he imagined a time when the aliens that oversaw human development were forced, by some circumstance in the universe, to call on the help of humans—humans whose “basic personality,” as it was called in Dianetics, though essentially good, had been scarred by their intergalactic parents. What would happen to the relationship between the parents—which he noted were also coded versions of the Holy Trinity—and their earthling children after the crisis was overcome?

Russell did not take up the idea, nor did he take up another idea that Campbell was then shopping—what if there was a technology that could essentially offer you immortality for the cost of giving up all of your irrational prejudices (an idea clearly extrapolated from Dianetic auditing)? But Campbell’s letter sketched in some battle lines between the two over the meaning of Charles Fort. The matter was mostly quiescent for the next couple of years, even as Campbell admitted to Russell that he was interested in Fortean topics such as teleportation, telepathy, and levitation. He just did not know that those subjects were ready to be attacked by scientists, since they were so far from the known forces of nature—bridges needed to be built from the known to the unknown, and the distance was too far. Still, he had authors working on the idea: Isaac Asimov published “Belief” in “Astounding”’s August 1953 issue, and Mark Clifton and Alex Apostolides published ‘What Thin Partitions’ in the September issue. Sam Moskowitz called the latter “by far the most masterful story ever written concerning levitation.”

By April 1952, niggling disagreements between Russell and Campbell—on Fort, but especially on the topic of Dianetics, which Russell saw as hogwash, dismissing the end goal of becoming sane (or clear) as ridiculous—had accumulated enough that Campbell had to address the matter. (Russell’s letters to Campbell no longer exist, as far as I know.) Campbell wrote,

“Generally, we’re in agreement on most of the aspects we’ve touched on; I might say that our disagreement over the value of Fort’s work is, perhaps, typical of what disagreements we have. I hold that Fort’s work was definitely ‘con’ data—confusing. Fort collected data as a pack-rat collects stuff. There is no selectivity; his information is not digested [sic], or integrated. Throwing a mass of undigested data at people is an old habit of our culture—and a stinking bad one, too. Data is absolutely useless until it is organized. The multiplication tables are data; they’re absolutely useless for anything but doing multiplication—and until you learn to see that real problems in real life require multiplication, the tables are undigested and undesired data. What problem does this data refer to and help to solve?

“Fort was angry that science did not accept his data, and immediately use it. So Fort damned science, and damned all the data science had! He was guilty in far greater degree that science [sic]; he didn’t digest the data of science, he simply rejected it in toto. The organization he made of his data is, therefore, utterly useless, because it doesn’t tie in with the actual data of science. Fort was a Mystic; he said, in essence, reject all there ideas, and see the importance of mine!

“I’ve never rejected the data—I’ve just questioned it most ferociously, because Fort was such a thuroughly [sic] unstable, unreasonable, unselective, and unintegrated personality that I couldn’t trust his data.

“Newspaper clippings are not reliable, per se; they can be used only when there are multiple reports oft he same event, continued over a period of time.

“Look, the mystics have been saying for millenia [sic] ‘All is illusion; the physical works is illusion without substance.’

“today, the physical scientist is saying ‘All mater is illusion; the physical world is illusion without substance.’

“They are, then, in complete agreement? By no means! The mystic says “This I know within me; it is not something that can be questioned and argued. It must be understood by faith and belief, and cannot be explained.’

“The physicist says, ‘This we know by studying the nature of matter; we find that it is actually composed of electric, magnetic and other force fields, which have the following characteristics . . . . . . The reason it appears to be solid is as follows . . . . . .’

“The mystic, down the ages, has been charachterized [sic] by the inability to communicate his findings; Jesus could walk on water, but his own disciple, in his presence, couldn’t do it. Jesus had powers which he was totally unable to communicate, although he could use them.

“Mysticism failed because it didn’t learn how to teach. It could do, but not explain or teach. Physical science hasn’t been able to do a lot of things mysticism did—but it can do something a lot more important. Every gain that physical science has made, it has been able to communicate fully. It’s not adequate for human beings to simply know-thin; they must be able to explain-without if the race as a whole is to benefit.

“It must not be communication at a subliminal level, either; emotional feeling is not adequate communication. There mist be communication at the verbalized, conscious level.

“The problem is, essentially, to develop a communication technique that can communicate all human experience. When the mystic makes contact with the Essence of God, he must be able to communicate the understanding achieved in such a fashion that other human beings actually succeed in doing the same. The root essence of physical science is that anyone can learn it, and practice it. It’s communicable knowledge-understanding.”

Nominally, this was about Fort, but it was really about Hubbard and Dianetics. Campbell was becoming irritated by Hubbard’s approach. In a letter written the next month, Campbell said,

“Eric. my intention is to bring attention to the existance [sic] pf phenomona [sic] outside the range of existant [sic] physical science. I deeply want to attract the attention of physical scientist [sic], whom I respect for good and sufficient reason (they’ve produced results in making things actually work) to problems of the real world that I feel are acute and important.

“Fort and I are, in other words, in full agreement on the goal. Hubbard and I were in full agreement on the goal. But Hubbard I now recognize made the same error Fort did—and for the same reason, I suspect.

“Any human being wants to feel that he has real existance [sic], and the only way to detect the reality of your existance [sic] is by effecting the world around you. A ghost would feel horribly unreal . . . “ goes on to say attacks on science were a way of feeling real. leaves fort behind and concentrates on hubbard. then: “Fort did a lot of shin-kicking, too. When I first read his books, he kicked my shins, but good. He was trying to sell me doughnuts for breakfast, and the method of salesmanship made me exceedingly disinterested in tasting the product.

“He didn’t bother to find out why physical scientists wouldn’t accept his ideas; had he done so, he could have found out what to do about it.”

Now, it may be that Campbell wanted science to take these matter seriously; and it may even be that Hubbard did, too, though this is less clear. But Fort was never really interested in getting science to take up his ideas and absorb them: he did not want his fact to become part of science; he was trying to transcend science. It was a so-called Dominant—what could also be called an era—that was being left behind. Campbell continued to voice this same objection to Fort over the next several years, though it became increasingly untethered from Fort—it’s not clear that Campbell had re-read Fort in more than a decade—and a way of talking about his frustrations with Hubbard, especially, but others interested in fringe scientific ideas: that they were not doing what was necessary to have their ideas taken seriously.

He wrote in October 1952, “Fort was insisting that someone else do the work of integrating them, and refusing to organize and interpret the data into intelligible stuff himself. For that, Fort should have been shown the door. He was too lazy to do the hard work; he wanted it done for him, and was very petulant because no one would. It was too damned much of a case of ‘Let’s you and him have a fight, huh?’

His data was valid. It contained important understandings, and important clues. In that, he was right. But why didn’t _he_ do some of the hard work of integrating it and finding the pattern, instead of frothing about how everyone else wouldn’t do that work?” As an example, he pointed out in May, “If he believed in the validity of poltergeist, why didn't he, personally, make a good, hard try at getting some understanding of what could be done to produce the phenom—-[sic] instead of shrieking that it must be done?

“Collecting data as he did is the smallest and least step of a job of research; the biggest and most important job is sifting data to determine which ones are critical, which ones are clues pointing the way to a solution.”

Instead, Fort only debunked—he destroyed without building, Campbell said, which wasn’t exactly true—Fort did have a vision of the future, it just wasn’t one in which all knowledge was subsumed by science. Campbell could not see that, though: science was, for him, still the ultimate arbiter of what counted as true—it was just slow in building up theories around facts, necessarily so. And for Campbell, Fort obviously wanted the approval of scientists—or, more accurately, Hubbard did: Fort “deeply wanted the attention of physical scientists, whom he actually respected somewhat unduly, to problems of the real world he recognized as being acute and important,” Campbell said in May 1952, and “Fort wouldn’t have been so violently insistant [sic] on attracting their attention if he hadn’t recognized, deeply, the high competence of the scientific method. Why didn’t he try, instead, to get theologians to study his data? Or mediums? The occultists and mystics would have listened to him gladly! Why, of all groups, did he belabor the physical scientists?”—which reads not like an interpretation of Fort, but like an extension of an argument he’d been having with Hubbard.

The matter was so important to Campbell because he thought that, through his science fiction magazine, he was laying the groundwork for this new science—creating the conditions for a better world. Russell did not develop Campbell’s idea about a machine that granted immortality for the cost of a person’s irrationalities, but Mark Clifton did (and his short stories became the basis for a novel). After Russell said something negative about Clifton’s work—the exact remark is unknown—Campbell responded in October 1952, “I’m trying to introduce the proposition of sciences beyond those currently known and accepted. But Eric PLEASE believe me; Charles Fort made a mistake. The error was his. He _insisted_ that the scientists understand him when he explained it all to them in Swahili. He even repeated it in Hindustani, and still the dolts wouldn’t listen to him. The one thing he didn’t try was to explain it in their stupid old language; it was obviously up to them to learn _his_ language, because he had something important to say.”

This was a manipulative strategy, he admitted, getting humankind to take its medicine with sugar—but take it no matter what. He told science fiction writer and editor Paul Anderson (who had published Heinlein’s “Lost Legacy”): “I’ve got Ray Jones and E.F. Russell and Isaac Asimov and Chad Oliver working on different aspects of it. We are, in essence, trying to teach the most thoughtful, speculative and philosophical group of Mankind--the science-fiction readership--a quite new viewpoint. It isn’t something they know they want to learn; therefore we have to do it by entertaining them enough so that they’ll accept the new ideas for the _sake of entertainment_, rather than for the _sake of the idea_.

But actually, in the long run, it makes little difference why they originally accept the idea--for fun, or for serious education; in either case the idea has been entered, and thought about, and will have an effect on the individual’s total philosophy. I drink orange juice in the morning because it tastes clean and sweet and fresh--because it makes my mouth feel good. I don’t drink it because my system needs glucose after the night fast, and because my system needs the organic acid to maintain the pH buffering effects, nor because ascorbic acid is vital to my nerve-system metabolism. What difference? I drink sugar and citric and ascorbic acids; I didn’t know I wanted them, but they make me feel good.”

The eat-your-spinach mentality was an adult one, Campbell thought—this went back to his story about aliens and human children that he offered to Russell: humanity was on the brink of adulthood, if it could move on to understand these unseen, unknown forces and master them. Ultimately, that was Fort’s problem—he remained scarred by a childhood event, and no doubt would have benefitted from some auditing, if only he had lived long enough: “I have a hunch that Fort was scared blue with pink polka-dots of getting anywhere near those forces; he probably contacted some of it accidentally during early childhood, got smacked down by it, and wouldn’t ever go near it again himself. Those forces lie beneath the sub-nuclear particles; uranium fission is a gentle release of a side-swipe of a minor readjustment of those forces. Get careless, or frisky with them, and you’ll get your come-_way_-uppance.” Fear kept Fort from exploring the workings of the anomalies he had identified.

There is a family resemblance between Campbell’s views from the 1940s and his views from the 1950s: in both cases he thought Fort could be a wellspring of science fiction and of science. By the 1950s, though, he was irritated with Fort for not doing more to get scientists to acknowledge his data and work with it—an irritation that was not voiced in the 1940s, as far as I know, and probably had more to do with Campbell’s own frustrations getting scientists to understand his ideas about new sciences. So he was tempting them, both by trying to work out enough science to his ideas to show them plausible and by tricking them by making the ideas intriguing: drink the orange juice because it’s good for you . . . and because it’s tasty.

The latter view of Fort, as inadequately addressing his ideas to science, seems to have solidified into Campbell’s primary idea about Forteanism. In the mid-1950s, Russell wrote a book on Fortean phenomena—“Great World Mysteries”—and tried to place parts of it as articles in Astounding. Campbell was not too pleased with the ideas—one was on the Marie Celeste, which he thought was overdone—nor Russell’s approach to Forteanism, which he thought hagiographic rather than scientific: “Are you interested primarily in validating Charles Fort, the individual—-or the reality of the great problem Fort wanted attacked?” He also did not like what he took to be Fort’s scolding of scientists, though he admitted Russell was much more reasonable: “Fort was an ill-tempered, impatient, and stupid man . . If you were the first in the field, and didn’t have the sour memory of Fort and his offensive tactics standing always in your way, the way you approach the mysteries would make them challenging, interesting, and would inspire work on them. If you don’t agree with that general idea . . . . why don’t you act the way Fort did?”

Campbell was interested in what Russell had to say about levitation—though he knew that subject would not be explored by scientists for a long time. But, as far as I know, Russell did not get an article on levitation into “Astounding.” A few parts of his book did appear in the magazine “Fantastic” And he did get an article on the medium Eusapia Palladino, a long-time subject of Fortean speculation, into “Astounding.” By this point, the correspondence between the two men had declined quite a bit, and Russell had drifted somewhat from Forteanism, if not Fort, as though writing the book had quieted that part of his mind.

Russell was surprised, it almost seems, by the amount of emotion he felt when Tiffany Thayer passed, in August 1959, as he admitted to Campbell. Campbell responded in his own way, empathetic, though also cool, analytical: “I had, of course, heard of Tiffany Thayer’s death; it happens I never had any real contact with him—-only through his interests did I know him. . . The depression you felt over Thayers’ death [sic] was, I suspect . . . The deep and heavy feeling of ‘Who, now, is left to carry on…?’ . . .

“Thayer may have done a lot to carry on the effects of Fort’s work, for instance, but he was in no sense a replacement for Fort—-and there never will be a replacement for” either of them.”

It was almost an apology, of sorts, to Fort, as well—since in earlier correspondence Campbell had insisted that Fort would be forgotten: he was no better than all the other mystics, having had an experience, but never bothering to explain it scientifically, and so of no use to future scientists or historians of science. Here Campbell was offering that Fort belonged to the elite, to the irreplaceable.

And, indeed, for all the irritation Campbell had about Fort, it’s clear that annoyance sprang, in part, from affection: both were involved int he same project, but Campbell thought Fort had done it wrong, and set back the movement. By the late 1950s, though, on some level, Campbell had to be coming to terms with the fact that he was also not going to revolutionize science on his own. Look at what had happened to Dianetics over the previous decade!

So it is fitting, in a way, what happened a year before Thayer’s death, in 1958.

Back in 1931, when the Fortean Society was first organized, Fort wanted no part of it—but was willing to join a group if it was called the “Interplanetary Exploration Society. After all, according to his cosmology—which he didn’t believe!—the other planets were only a few hundreds of miles away, so reachable given a change in perspective. Why not, then, a Society dedicated to traveling to them? Of course, such a Society was not founded.

Twenty seven years later, Campbell had an idea. It was an extension of his hope to have amateurs contribute to science by doing the dirty work—the work he thought Fort had refused to do—the dirty work of making fringe sciences respectable enough that genuine scientists would the take up the problems. It was, as well, a twist on an old idea by the science fiction writer Ray Cummings, what he called the Gentleman’s Scientific Association. Campbell thought there should be a journal to go with it, and he organized a few meetings, as well as—at the very least—a New England chapter, that included his writer Hal Clement.

Campbell chose the group’s name because, he wrote, “the very fact of the present reality of off-this-world vehicles helps to establish in a general audience the fact that speculative thinking does, and has, paid off.” He was thinking of rockets, and how science-fictioneers had promoted them long before scientists took rocketry seriously. They were a way to reach distant planets quickly—his cosmology was more expansive than Fort’s, but technology would annihilate distance in space, just as it had on earth. And so the name was the same: Campbell called it the “Interplanetary Exploration Society.”