Griggs, 1947

Griggs, 1947 A Fortean by association, if not inclination.

John M. Griggs was born in Evanston, Illinois around 1909 to Gilbert M. and Cecil E. Griggs. Gilbert, born 1880, had come from New York and was a cashier in a brokerage house; Cecil, some six years his senior, had come from Maine. The Griggs family had come to Illinois by 1900—perhaps even earlier—and Cecil’s family, the Zimmermans, had been there since at least 1880. She attended Northwestern University. The two married in 1906, John their first child. Around 1916, Marion, a daughter, was born.

By 1930, with Gilbert, Cecil, and Marian still in Illinois, John was in Detroit, pursuing a career as an actor. He was 21. His obituary has his first Broadway appearance in George Arliss’s “Merchant of Venice,” but as best I can tell that ran in 1928 and Grigg’s name doesn’t start to appear on the Internet Broadway Database before the early 1930s. At any rate, we can say that he was in New York by the early 1930s at the latest. By 1940, he was married to an English-born actress Alice—who may have performed under the stage name Mary Newnham Davis. Alice was about six years older than Griggs, not unlike the age differences in his parents. His obituary has him broadcasting for Voice of America during World War II, although I can find no enlistment records. Griggs’ mother, Cecil, died in August 1942.

John M. Griggs was born in Evanston, Illinois around 1909 to Gilbert M. and Cecil E. Griggs. Gilbert, born 1880, had come from New York and was a cashier in a brokerage house; Cecil, some six years his senior, had come from Maine. The Griggs family had come to Illinois by 1900—perhaps even earlier—and Cecil’s family, the Zimmermans, had been there since at least 1880. She attended Northwestern University. The two married in 1906, John their first child. Around 1916, Marion, a daughter, was born.

By 1930, with Gilbert, Cecil, and Marian still in Illinois, John was in Detroit, pursuing a career as an actor. He was 21. His obituary has his first Broadway appearance in George Arliss’s “Merchant of Venice,” but as best I can tell that ran in 1928 and Grigg’s name doesn’t start to appear on the Internet Broadway Database before the early 1930s. At any rate, we can say that he was in New York by the early 1930s at the latest. By 1940, he was married to an English-born actress Alice—who may have performed under the stage name Mary Newnham Davis. Alice was about six years older than Griggs, not unlike the age differences in his parents. His obituary has him broadcasting for Voice of America during World War II, although I can find no enlistment records. Griggs’ mother, Cecil, died in August 1942.

It was his voice that made him famous. He was heard on over 5,000 radio programs, including “The House of Mystery” and was a well-known contributor to CBS. He later did some television work. Griggs was also an ardent film collector. He also copied some of the rarer films and sold them under the name Griggs-Moviedrome. Eventually, the bulk of his collection went to Yale University—the Beinecke Library, joining the other Fortean collection, Getrude Hill’s Robert Louis Stevenson material—where his son was studying.

John M. Griggs died in February 1967, two years after his father passed. His wife, sone Timothy, and sister Marian (Vrieze) all survived him.

Apparently while he was still in Illinois, Griggs became friend with Robert L. Farnsworth and he was on hand in 1942 when Farnsworth incorporated the United States Rocket Society: although Griggs was in New York, he was officially the Society’s Vice President and promotions manager. Like Farnsworth, though, Griggs’ didn’t really start making the national news until after World War II—maybe his promotional efforts went nowhere, the world waiting for the end of the war before accepting the possibility of rockets, or maybe he wasn’t really doing much. Either way, it was 1946 before Griggs and the Society were in the mainstream media.

And when media attention came, it was a big flourish, although like a comet it passed soon enough. The Rocket Society and Griggs got a mention in Coronet magazine (which published another Fortean, R. DeWitt Miller); the reference confirmed that the Griggs of the Rocket Society was also, as the magazine put it, a “CBS Radio Story Teller.” In January of that year, Robert Richards, a United Press correspondent, got stories about Griggs and the Rocket Society in papers around the nation:

“John Griggs owns an ordinary neck, and likes it, but he’s going to fly to the moon.

‘All I need is a sponsor,’ he said today. ‘You get me an industrial firm to foot the bills, baby, and I’m off—like a big fire-cracker.’

Griggs, 37-year-old neck and all, is vice president of the United States Rocket Society. The Society, with headquarters near Chicago, has 1,600 members and is affiliated with the British Astronautical Society.

‘I’m telling you all this only to make it clear that we are no fly-by-nights,’ Griggs explained. ‘People have been laughing at us for a long time but now that the Army has established radar contact with the moon, I guess they’ll stifle their chuckles and pay attention.’

Griggs, who is a radio actor in private life, said that the rocket society probably would fire several projectiles loaded with chemicals at the moon before anyone actually climbed aboard for an all-out ride.

‘We’ll observe this operation through telescopes,’ he explained, ‘and try to find out just wha happens when the rockets reach home plate.’

Some people are trying to discourage Griggs and other society members from attempting such a trip.

‘They claim I’ll melt like butter in the daytime,’ he said, ‘and that I’ll be frozen into a solid mass come the night. It could be, but we’ll see about that.’

Griggs and his colleagues believe that its mighty important for Americans to reach the moon first.

‘If the next war comes, it’ll be terrible,’ he said. ‘The first nation that swings its atomic punch will probably win. If we have our atom installations on the earth, enemy spies probably will locate them even before the war starts.”

That was how the story appeared in the Huntingdon Pennsylvania Daily News on 29 January, under the banner “Rocket Society Head Ready for Trip to Moon; Seeks Sponsor.” Other newspapers re-wrote the article to emphasize different aspects—the danger of the trip, for example, and thus Griggs’ derring-do (Nehosho, Missouri Daily News, same date). Or the international politics: a day before The Brooklyn Daily Eagle added Griggs’ quote, “But if we locate our atomic bombing bases in the moon and let all other nations know about it, well, they’ll think twice before they jump the gun and start a fight.” Incidentally, the same paper noted “Any man-carrying rocket would have to be as large as a small sky-scraper.” That last bit underlined the tone which ran through all the different re-writes: that Griggs’ was eccentric and the idea of sending a rocket to the moon slightly ridiculous. This was not a serious news story, whatever the U.S. Rocket Society may have hoped.

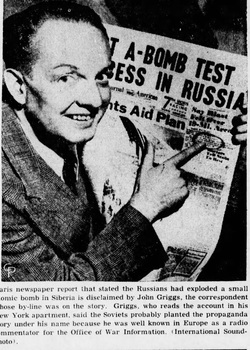

Events, though, seemed support Griggs in a very personal way. November 1947 saw some newspapers carrying a report from Paris that the Russians had exploded an atomic bomb—making them the second country to do so, and ending the U.S. brief period of supremacy: America’s once-ally was now an existential threat. The original reports were carried under the byline “John Griggs” Other events seemed to confirm the initial reporting—even as it was revealed that Griggs’ name was a pseudonym to protect the journalist—but, in the end, it all proved false: The Soviets would not explode an atomic bomb until 1949. John Griggs, the radio actor, thought the story involved him. In a wire story from 14 November 1947 (in the Monongahela Daily Republican), he was shown reading the story in his New York apartment. He said Soviets probably plated the propaganda story and used his name because he was well known on the radio from his work with the Office of War Information.

Possibly having his name co-opted by Soviet propagandists was the height of Grigg’s involvement with the rocket movement, at least as far as I can see. His connection was mentioned a few more times in the 1940s—Wendy Warren’s gossip column “Luncheon Scoops” from June 1949, an AP rundown (bylined Mark Barron) of Broadway goings-ons—but for a director of promotions he was curiously out of the limelight, especially when compared to Farnsworth, his friend and the Society’s president. As far as I can tell from my perusal of a few issues of Rockets—the Society’s official ‘zine—and on-line indices, Griggs rarely appeared in the Society’s publications. He got a small mention in 1946 for obtaining stills from a movie, and published something in 1955 on life under high-pressure, which also got him mentioned by the (unaffiliated) Chicago Rocket Society. But that was about it.

Which is fitting, given that his connection to the Fortean Society was similarly scant—and, seemingly, completely a result of his connection to rocket-fanaticism. His name is only mentioned once in the pages of Doubt. And nowhere can I find him talking about Charles Fort or the Fortean Society—again unlike Farnsworth, who made it into Doubt a few times, and who discussed Fort in both newspaper interviews and his own writing. The over-riding impression is that Griggs was a rocket-enthusiast, but mostly as a diversion—it was secondary to his career, perhaps tertiary given his interest in film-collecting—and a Fortean only by association, a member because Farnsworth was a member and the U.S. Rocket Society promoted the Fortean Society, and vice versa.

The one mention comes in Doubt 14 (Spring 1946)—the same issue that made the only mention of Martin J. Fritz. Here, though, the designation is certain. Thayer thought rocketry peculiarly Fortean, given Fort’s own interest in interplanetary exploration—albeit Fort didn’t imagine rockets necessary, since he argued the planets were so close. Thayer wrote,

“When we were founding the Fortean Society, Charles Fort refused to join. We wanted to name him Honorary President, or to give him some other title, one especially calculated to remove all onus of vanity or self-exploitation, of which he had an insuperable dread. ‘No,’ said he, ‘call it the Interplanetary Exploration Society and I’ll come in, but not as long as it has my name on it.’

“Ever since, we have had the warmest cordiality for the rocketeers, and kept tabs on their progress here and abroad until censorship interfered.

“Now we are delighted to announce that the President of the United States Rocket Society, the well known pioneer in this field, R. L. Farnsworth, and one of the vice-presidents, John M. Griggs are members of the Fortean Society, and will thenceforward be our liaison—transportation-wise—with Luna, Mars, and points up.”

Griggs lived long enough to see satellites launched into orbit, but not to see men walk on the moon. That remained forever a dream.

John M. Griggs died in February 1967, two years after his father passed. His wife, sone Timothy, and sister Marian (Vrieze) all survived him.

Apparently while he was still in Illinois, Griggs became friend with Robert L. Farnsworth and he was on hand in 1942 when Farnsworth incorporated the United States Rocket Society: although Griggs was in New York, he was officially the Society’s Vice President and promotions manager. Like Farnsworth, though, Griggs’ didn’t really start making the national news until after World War II—maybe his promotional efforts went nowhere, the world waiting for the end of the war before accepting the possibility of rockets, or maybe he wasn’t really doing much. Either way, it was 1946 before Griggs and the Society were in the mainstream media.

And when media attention came, it was a big flourish, although like a comet it passed soon enough. The Rocket Society and Griggs got a mention in Coronet magazine (which published another Fortean, R. DeWitt Miller); the reference confirmed that the Griggs of the Rocket Society was also, as the magazine put it, a “CBS Radio Story Teller.” In January of that year, Robert Richards, a United Press correspondent, got stories about Griggs and the Rocket Society in papers around the nation:

“John Griggs owns an ordinary neck, and likes it, but he’s going to fly to the moon.

‘All I need is a sponsor,’ he said today. ‘You get me an industrial firm to foot the bills, baby, and I’m off—like a big fire-cracker.’

Griggs, 37-year-old neck and all, is vice president of the United States Rocket Society. The Society, with headquarters near Chicago, has 1,600 members and is affiliated with the British Astronautical Society.

‘I’m telling you all this only to make it clear that we are no fly-by-nights,’ Griggs explained. ‘People have been laughing at us for a long time but now that the Army has established radar contact with the moon, I guess they’ll stifle their chuckles and pay attention.’

Griggs, who is a radio actor in private life, said that the rocket society probably would fire several projectiles loaded with chemicals at the moon before anyone actually climbed aboard for an all-out ride.

‘We’ll observe this operation through telescopes,’ he explained, ‘and try to find out just wha happens when the rockets reach home plate.’

Some people are trying to discourage Griggs and other society members from attempting such a trip.

‘They claim I’ll melt like butter in the daytime,’ he said, ‘and that I’ll be frozen into a solid mass come the night. It could be, but we’ll see about that.’

Griggs and his colleagues believe that its mighty important for Americans to reach the moon first.

‘If the next war comes, it’ll be terrible,’ he said. ‘The first nation that swings its atomic punch will probably win. If we have our atom installations on the earth, enemy spies probably will locate them even before the war starts.”

That was how the story appeared in the Huntingdon Pennsylvania Daily News on 29 January, under the banner “Rocket Society Head Ready for Trip to Moon; Seeks Sponsor.” Other newspapers re-wrote the article to emphasize different aspects—the danger of the trip, for example, and thus Griggs’ derring-do (Nehosho, Missouri Daily News, same date). Or the international politics: a day before The Brooklyn Daily Eagle added Griggs’ quote, “But if we locate our atomic bombing bases in the moon and let all other nations know about it, well, they’ll think twice before they jump the gun and start a fight.” Incidentally, the same paper noted “Any man-carrying rocket would have to be as large as a small sky-scraper.” That last bit underlined the tone which ran through all the different re-writes: that Griggs’ was eccentric and the idea of sending a rocket to the moon slightly ridiculous. This was not a serious news story, whatever the U.S. Rocket Society may have hoped.

Events, though, seemed support Griggs in a very personal way. November 1947 saw some newspapers carrying a report from Paris that the Russians had exploded an atomic bomb—making them the second country to do so, and ending the U.S. brief period of supremacy: America’s once-ally was now an existential threat. The original reports were carried under the byline “John Griggs” Other events seemed to confirm the initial reporting—even as it was revealed that Griggs’ name was a pseudonym to protect the journalist—but, in the end, it all proved false: The Soviets would not explode an atomic bomb until 1949. John Griggs, the radio actor, thought the story involved him. In a wire story from 14 November 1947 (in the Monongahela Daily Republican), he was shown reading the story in his New York apartment. He said Soviets probably plated the propaganda story and used his name because he was well known on the radio from his work with the Office of War Information.

Possibly having his name co-opted by Soviet propagandists was the height of Grigg’s involvement with the rocket movement, at least as far as I can see. His connection was mentioned a few more times in the 1940s—Wendy Warren’s gossip column “Luncheon Scoops” from June 1949, an AP rundown (bylined Mark Barron) of Broadway goings-ons—but for a director of promotions he was curiously out of the limelight, especially when compared to Farnsworth, his friend and the Society’s president. As far as I can tell from my perusal of a few issues of Rockets—the Society’s official ‘zine—and on-line indices, Griggs rarely appeared in the Society’s publications. He got a small mention in 1946 for obtaining stills from a movie, and published something in 1955 on life under high-pressure, which also got him mentioned by the (unaffiliated) Chicago Rocket Society. But that was about it.

Which is fitting, given that his connection to the Fortean Society was similarly scant—and, seemingly, completely a result of his connection to rocket-fanaticism. His name is only mentioned once in the pages of Doubt. And nowhere can I find him talking about Charles Fort or the Fortean Society—again unlike Farnsworth, who made it into Doubt a few times, and who discussed Fort in both newspaper interviews and his own writing. The over-riding impression is that Griggs was a rocket-enthusiast, but mostly as a diversion—it was secondary to his career, perhaps tertiary given his interest in film-collecting—and a Fortean only by association, a member because Farnsworth was a member and the U.S. Rocket Society promoted the Fortean Society, and vice versa.

The one mention comes in Doubt 14 (Spring 1946)—the same issue that made the only mention of Martin J. Fritz. Here, though, the designation is certain. Thayer thought rocketry peculiarly Fortean, given Fort’s own interest in interplanetary exploration—albeit Fort didn’t imagine rockets necessary, since he argued the planets were so close. Thayer wrote,

“When we were founding the Fortean Society, Charles Fort refused to join. We wanted to name him Honorary President, or to give him some other title, one especially calculated to remove all onus of vanity or self-exploitation, of which he had an insuperable dread. ‘No,’ said he, ‘call it the Interplanetary Exploration Society and I’ll come in, but not as long as it has my name on it.’

“Ever since, we have had the warmest cordiality for the rocketeers, and kept tabs on their progress here and abroad until censorship interfered.

“Now we are delighted to announce that the President of the United States Rocket Society, the well known pioneer in this field, R. L. Farnsworth, and one of the vice-presidents, John M. Griggs are members of the Fortean Society, and will thenceforward be our liaison—transportation-wise—with Luna, Mars, and points up.”

Griggs lived long enough to see satellites launched into orbit, but not to see men walk on the moon. That remained forever a dream.