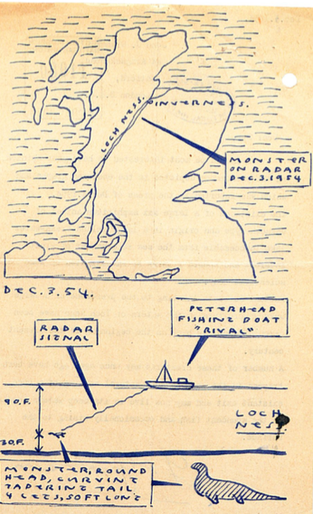

Graham's drawing of the sonar sighting of the Loch Ness Monster, December 1954, for the benefit of the Museum of Natural History.

Graham's drawing of the sonar sighting of the Loch Ness Monster, December 1954, for the benefit of the Museum of Natural History. A too-helpful Fortean.

John J. Graham was a British Fortean who came to the Society in the early 1950s. I have virtually no information on him besides that, a few particulars to specify the generalities, but that is it. He was associated with a Mrs. D. Graham. He had a London address, 44 Arngask Road, Catford, where he preferred his Fortean correspondence to go; and he had an address on the Isle of Man, 11 Upper Church Street, Douglas. The Isle of Man was for some Fortean interest as a home to Gef the Talking Mongoose—otherwise known as the Haunting of Cashen’s Gap—a poltergeist case that was investigated by Harry Price, Hereward Carrington, and Nandor Fodor during the 1930s.

Everything else I know about Graham regards his Fortean activities; he corresponded with the New York office; he corresponded with Eric Frank Russell; he had materials incorporated into Doubt; and he even corresponded with the Natural History Museum in London regarding Fortean topics. All told there are eight letters from him to Russell (plus one from D. Graham); seven letters from Tiffany Thayer to Russell that mention Graham; three mentions of the name Graham own Doubt; and one (extant) letter from Graham to the museum, plus some associated materials, including responses. These run from 1952 to 1957, inclusive.

John J. Graham was a British Fortean who came to the Society in the early 1950s. I have virtually no information on him besides that, a few particulars to specify the generalities, but that is it. He was associated with a Mrs. D. Graham. He had a London address, 44 Arngask Road, Catford, where he preferred his Fortean correspondence to go; and he had an address on the Isle of Man, 11 Upper Church Street, Douglas. The Isle of Man was for some Fortean interest as a home to Gef the Talking Mongoose—otherwise known as the Haunting of Cashen’s Gap—a poltergeist case that was investigated by Harry Price, Hereward Carrington, and Nandor Fodor during the 1930s.

Everything else I know about Graham regards his Fortean activities; he corresponded with the New York office; he corresponded with Eric Frank Russell; he had materials incorporated into Doubt; and he even corresponded with the Natural History Museum in London regarding Fortean topics. All told there are eight letters from him to Russell (plus one from D. Graham); seven letters from Tiffany Thayer to Russell that mention Graham; three mentions of the name Graham own Doubt; and one (extant) letter from Graham to the museum, plus some associated materials, including responses. These run from 1952 to 1957, inclusive.

The evidence, such as it is, suggests that Graham was introduced to Fort in the early 1950s, though I do not know the source. On 23 September 1952, Mrs. D. Graham wrote to Russell—after contacting Thayer in new York and being redirected—requesting a copy of the Books of Charles Fort. There is then an eight-month gap, though it seems other correspondence might have taken place. On 1 May 1953, John J. Graham, writing from the same London address as Mrs. D. Graham, wrote to Russell requesting two additional copies of Doubt (which he paid for): this suggests he’d already been in contact with Russell to get copies of Doubt in the first place, though it is possible that Russell merely sent them along when he received the book request.

In addition, Graham revealed himself to be a dedicated Fortean, in practice if not in membership. He sent along two stories about an unidentified cigar-shaped object above the Isle of Man, one story from October 1950, the other from June 1951. He went on to note that he had about 10,000 notes—!!—on various scientific subjects, though not many, apparently, on the kind of anomalous phenomena that the Society preferred. He did, though, have many on sky objects, and offered to send some along, if Russell was so disposed.

This began two of the threads that wound through the correspondence between Graham and Russell: requests for issues of “Doubt” and the provision of clippings. By the time he wrote two weeks later—and this was too-frequent correspondence as far as Russell and Thayer thought—Graham had acquired Doubt issues 33-40, but was asking for any other back numbers. He sent another cutting, this one from the “Daily Mail.” And he started the third thread: his constructive criticism of the Society. He asked Russell to please answer his earlier letter—which almost certainly irked Russell—and then enumerated his complaints. He appreciated that the Society published Forts notes but other material “to say the least crude and in my opinion best left out.” He gave russell advice about interplanetary travel, since he’d learned that Russell was a science fiction writer: “Before the end of this century space will vibrate to the noise of great ships heading out from this earth towards the moon. There will be expeditions and disasters and most terrible of all will interplanetary warfare [sic] that no-one can avert.” Great cities will be destroyed. He added that he did not like N. Meade Layne’s contributions to the Society—Thayer poked fun at him, but UFOs were too serious to be an object of fun.

With the pattern now established, the rest of the correspondence continued on the same lines. In the middle of June, Graham wrote from the Isle of Man: he’d collected Doubt numbers 29-40 and was looking for others. His brother wanted a copy of The books. Why was no one writing a new Fortean book using all the material that had been collected? (Thayer was busy trying to get members to compile essays on the various topics, but having trouble finding takers.) He sent some more clippings. Another letter from later in the month included yet more clippings and requests for additional Doubts.

Graham may (or may not have) made his first appearance in Doubt at this time. Number 41 (July 1953) included a generic credit to someone with the surname Graham. John J. was not the only Fortean with that last name. There was also Roger P. Graham, who contributed to N. Meade Layne’s Borderlands Research Journal (aka Round Robin). It is impossible to know which Graham contributed here—indeed, all the contributions to Doubt are impossible to specify, since they only use the name Graham. The only reason I know the full name John G. Graham is he corresponded with Russell. (And most of those letters are just signed J. Graham, though the J could also be a G. Only once did he give his full first name and middle initial.)

By August 1953, Graham was back at Russell’s heel. He had not yet received issue 41. Or 42 or 43. He was also looking for issues 20 and 21. And he wanted the address for the British Interplanetary Society as well as the U.S. equivalent. He had complete designs, he said, for motors, reactors, and the other components necessary to equip an interplanetary ship. Some publicity for his work in Doubt would also help, he said. And contacts with anyone else doing similar work. He concluded, “I can design anything.” Eleven days later, he wrote asking for yet more back issues. He also sent 75 news clippings, and offered to copy Fortean data out of books he was reading.

At some other point in the month—the letter was just dated “August”—he had yet more advice, more supplies, and more requests. Did Russell have a picture of Charles Fort? Graham needed one. He sent in 62 more clippings—that’s more than 130 in the month alone. Graham said that the Lewisham library had a copy of “Lo!” (almost certainly the Gollancz edition) and suggested Russell offer them copies of “Lo!” He should write them. By the way, he wondered, why weren't The Books published in England? They should be. Copies were hard to get. Indeed, the Society should be reorganized. The Fortean Society could be made into a company, and all of its profits—!!—could be put into Doubt. Thayer should hire a sales manager and open offices in New York and London. They should send a advertising pamphlet to universities and libraries.

Some time later in the year—this later was completely undated—Graham told Russell not to bother with the picture of Fort. (It’s not as though Russell had one at hand.) Graham said he’d buy a copy of The Books, and get it from there. He now wanted to buy Doubt 12 and 17-19, for which he included payment. He then mentioned that he’d been writing about interplanetary travel, and offered to send Russell some “fragments,” even part of a story, which he was offering Russell for free. This material could then be passed on to New York. In addition, he enclosed about 100 more news clippings.

At about this time, Thayer was sorting through the tidal wave of material, and hearing about Graham’s ideas. He said, Graham was “obsessed by weather, but in between the rain drops are a few dingbats of worth. Don’t stop him, just make the bastard pay.” The last comment suggested that Graham may have been paying for individual back issues but was, for whatever reason, reluctant to become a member and pony up for the subscription. But of course failure to pay was a common problem that Thayer faced. He carried a number of members gratis; “Doubt” and the Society were money-losing propositions that he paid for out of the meager amount he made from selling books and mostly from his own bank account. He’d advertised the books to universities and libraries; he’d swapped with other magazines to increase circulation. But both the Society and its magazine remained niche.

So when Thayer heard Graham’s helpful hints about making the Society profitable and larger—pie-in-the-sky rumination from some one who had no idea what he was talking about, nor any idea the lengths to which Thayer was going—Thayer could only scoff. (After all, Graham apparently wasn’t paying dues; why did he think others would?) “Please shoot Graham,” he told Russell in January 1954. “My check for two million dollars has been sent to Graham to perfect his system for making gold out of water. Now I know that the talking mongoose never was shot. It simply learned how to print,” he wrote the next month. “Maybe Graham will go away, or become King of Man. I sent him details of my formula for making gold out of water,” he told Russell in June.

In between these quips, Thayer ran what seem to have been Graham’s other contributions, though the same caveats apply to these as did the first one. Doubt 43 (February 1954—note: published six months after Graham requested it) carried a story about a girl walking her baby sister in a pram who had an arm blown off when something fell from the sky; both the RAF and USAF, who were active in the area, denied any responsibility. Graham was not the only one to contribute the story—do did Helen Knothe and some unnamed others. The following issue, published in April 1954, carried a story about ancient lotus seeds from China that were being grown in Washington, D.C. (not the only time a story like this was reported in Doubt; Arrow Mackey contributed one, too.) In this case, Graham was singled out as a “non-member,” which may have been Thayer’s way of goosing him to pay his dues.

Graham’s last (extant) letter to Russell was dated September 1954, and encapsulated the entire correspondence. It’s also the only typewritten letter from him in Russell’s archives. He wrote,

“I presume that your society stands for an extreme communism that is for abolishing organised [sic] society, therefore you attack all institutions utilising [sic] Forts [sic] attack in order to destroy science.

“Presumably Forts [sic] intention was to destroy existing beliefs by writing books ridiculing scientists for sale among males and bring in his own twin main ideas of contact with other worlds, and psychic subjects.

“Thus your attack is intended to destroy all organised [sic] society for good.

“Forts[sic] attack was intended to destroy existing scientific ideas in order to introduce the new ideas he had formulated.

“Two entirely different aims, but that Mr thayer [sic] is using Fort for his own ends.

“Yours truly, J. Graham”

That was par for the course as far as criticism of the Society went. Thayer was often attacked for making Forteanism political. And being accused of communism was common enough—Thayer came to see accusations of being red just a way to hating on something, free of any specific complaint. The kicker came with the postscript: “P.S.—-I will buy DOUBT from you as the Micros Book Co dont [sic] now stock it, they told me.” So for all the criticism, all the venom, he was still going to keep buying the magazine, and even, perhaps, become a member.

There are a couple of reasons Graham may not have any letters in Russell’s archive after September 1954. One may be that Russell stopped saving them, sending them instead to the trash bin. Another may be that Russell found Graham a different correspondent. Thayer remarked that same month, “Mike Jenkinson is our second Venusian correspondent. Can’t you dig up on from Saturn for a change? Anyway, Graham’s schemes would work better on Venus, so you did well to knock their heads together.” I do not know who Mike Jenkinson was (the other Venusian correspondent was Frederick G. Hehr), but there may have been letters shared between Jenkinson and Graham. A third reason is that Graham found a different—but related—enthusiasm, and a different institution to write.

Graham was in correspondence with the Museum of Natural History in December of 1954, three months after the seeming end of his connection to Russell. (We know it’s the same Graham because the address is the same.) The first letter, which is not in the Museum’s archives, was apparently dated 7 December and regarded sonar readings from the “Rival III.” Graham wanted to know the Museum’s opinion. The answer to Graham, as it came down, was a cleaned up version of a memo written by Hampton Widman Parker, who called it “press nonsense.” Apparently Graham had called the sonar “radar,” and because Graham had not bothered reading the stories, he pointed out that radar could not detect shape—and it was claimed the “Rival” had limned the monster’s outline. F. C. Fraser, who composed the actual reply, added that he had no special knowledge of the equipment used, and so was reluctant to opine on the matter. (From correspondence in the same file, it seems that this was Fraser’s general policy: offering no opinion on the matter of the Loch Ness Monster.

Graham, as he had with Russell, replied quickly, and brought to bear more questions—and more material generally. He said that he had learned the radar—as he kept calling it—in this situation could detect an outline, and so again asked for the Museum’s opinion. He also brought up another recent discovery—a peculiar creature captured in a net recently off Dungeness. I have not heard of this episode—and a quick search turned up nothing—but Dungeness is in the southern part of England, on the English Channel. Again, he wanted the museum’s opinion of the matter. Finally, he noted that supposedly extinct species may survive in a number places around the globe. Enclosed with his letter were two drawings. One was a map that showed Inverness and Loch Ness; a blow-up section showed the “Rival” and its relative position to the supposed creature as well as the monster’s outline. The other was a world map, showing the location of the Loch Ness Monster, the “Snow-Man,” and where the coelacanth was re-discovered; the bottom half was a blow-up of southern England, with the notation of the Dungeness creatures discovery on 18 December and a line drawing of the sea monster.

Fraser wrote again a week later, on the 29th of December. This was the last letter in the correspondence or, at least, the last preserved in the Museum’s archives. It was a terse closure, only two sentences long. The first dispatched with the sea monster of southern England: “The fish caught at Dungeness was a young Basking Shark.” The second reiterated Fraser’s insistence on not discussing the Loch Ness Monster: “I regret that I am unable to express any opinion about the Loch Ness record.” (Note that he did not say “Monster.”) There was no mention of the maps or Graham’s interest in what was only sporadically being called cryptozoology.

Graham, though, was not done with Forteanism. Thayer still had him in mind. In December 1954, around the time that Graham was asking the museum about the Loch Ness Monster, Thayer quipped to Russell—making reference to personal events I do not know anything about— “I am beginning to feel Graham’s awful power. Twice, recently, the world has stood still, and no one but Graham could have caused that, except yourself, of course, and I’m fairly sure you would have told me.” And he must have continued to have some association with the Society—as a member or a purchaser of individual issues, supplier of materials, and dispenser of advice, I do not know.

In June 1957, Thayer wrote to Russell once more, repeating a joke that, in the absence of any other information, must stand as the epitaph for Graham’s Fortean career: “Graham is obviously the reincarnation of the talking mongoose.”

In addition, Graham revealed himself to be a dedicated Fortean, in practice if not in membership. He sent along two stories about an unidentified cigar-shaped object above the Isle of Man, one story from October 1950, the other from June 1951. He went on to note that he had about 10,000 notes—!!—on various scientific subjects, though not many, apparently, on the kind of anomalous phenomena that the Society preferred. He did, though, have many on sky objects, and offered to send some along, if Russell was so disposed.

This began two of the threads that wound through the correspondence between Graham and Russell: requests for issues of “Doubt” and the provision of clippings. By the time he wrote two weeks later—and this was too-frequent correspondence as far as Russell and Thayer thought—Graham had acquired Doubt issues 33-40, but was asking for any other back numbers. He sent another cutting, this one from the “Daily Mail.” And he started the third thread: his constructive criticism of the Society. He asked Russell to please answer his earlier letter—which almost certainly irked Russell—and then enumerated his complaints. He appreciated that the Society published Forts notes but other material “to say the least crude and in my opinion best left out.” He gave russell advice about interplanetary travel, since he’d learned that Russell was a science fiction writer: “Before the end of this century space will vibrate to the noise of great ships heading out from this earth towards the moon. There will be expeditions and disasters and most terrible of all will interplanetary warfare [sic] that no-one can avert.” Great cities will be destroyed. He added that he did not like N. Meade Layne’s contributions to the Society—Thayer poked fun at him, but UFOs were too serious to be an object of fun.

With the pattern now established, the rest of the correspondence continued on the same lines. In the middle of June, Graham wrote from the Isle of Man: he’d collected Doubt numbers 29-40 and was looking for others. His brother wanted a copy of The books. Why was no one writing a new Fortean book using all the material that had been collected? (Thayer was busy trying to get members to compile essays on the various topics, but having trouble finding takers.) He sent some more clippings. Another letter from later in the month included yet more clippings and requests for additional Doubts.

Graham may (or may not have) made his first appearance in Doubt at this time. Number 41 (July 1953) included a generic credit to someone with the surname Graham. John J. was not the only Fortean with that last name. There was also Roger P. Graham, who contributed to N. Meade Layne’s Borderlands Research Journal (aka Round Robin). It is impossible to know which Graham contributed here—indeed, all the contributions to Doubt are impossible to specify, since they only use the name Graham. The only reason I know the full name John G. Graham is he corresponded with Russell. (And most of those letters are just signed J. Graham, though the J could also be a G. Only once did he give his full first name and middle initial.)

By August 1953, Graham was back at Russell’s heel. He had not yet received issue 41. Or 42 or 43. He was also looking for issues 20 and 21. And he wanted the address for the British Interplanetary Society as well as the U.S. equivalent. He had complete designs, he said, for motors, reactors, and the other components necessary to equip an interplanetary ship. Some publicity for his work in Doubt would also help, he said. And contacts with anyone else doing similar work. He concluded, “I can design anything.” Eleven days later, he wrote asking for yet more back issues. He also sent 75 news clippings, and offered to copy Fortean data out of books he was reading.

At some other point in the month—the letter was just dated “August”—he had yet more advice, more supplies, and more requests. Did Russell have a picture of Charles Fort? Graham needed one. He sent in 62 more clippings—that’s more than 130 in the month alone. Graham said that the Lewisham library had a copy of “Lo!” (almost certainly the Gollancz edition) and suggested Russell offer them copies of “Lo!” He should write them. By the way, he wondered, why weren't The Books published in England? They should be. Copies were hard to get. Indeed, the Society should be reorganized. The Fortean Society could be made into a company, and all of its profits—!!—could be put into Doubt. Thayer should hire a sales manager and open offices in New York and London. They should send a advertising pamphlet to universities and libraries.

Some time later in the year—this later was completely undated—Graham told Russell not to bother with the picture of Fort. (It’s not as though Russell had one at hand.) Graham said he’d buy a copy of The Books, and get it from there. He now wanted to buy Doubt 12 and 17-19, for which he included payment. He then mentioned that he’d been writing about interplanetary travel, and offered to send Russell some “fragments,” even part of a story, which he was offering Russell for free. This material could then be passed on to New York. In addition, he enclosed about 100 more news clippings.

At about this time, Thayer was sorting through the tidal wave of material, and hearing about Graham’s ideas. He said, Graham was “obsessed by weather, but in between the rain drops are a few dingbats of worth. Don’t stop him, just make the bastard pay.” The last comment suggested that Graham may have been paying for individual back issues but was, for whatever reason, reluctant to become a member and pony up for the subscription. But of course failure to pay was a common problem that Thayer faced. He carried a number of members gratis; “Doubt” and the Society were money-losing propositions that he paid for out of the meager amount he made from selling books and mostly from his own bank account. He’d advertised the books to universities and libraries; he’d swapped with other magazines to increase circulation. But both the Society and its magazine remained niche.

So when Thayer heard Graham’s helpful hints about making the Society profitable and larger—pie-in-the-sky rumination from some one who had no idea what he was talking about, nor any idea the lengths to which Thayer was going—Thayer could only scoff. (After all, Graham apparently wasn’t paying dues; why did he think others would?) “Please shoot Graham,” he told Russell in January 1954. “My check for two million dollars has been sent to Graham to perfect his system for making gold out of water. Now I know that the talking mongoose never was shot. It simply learned how to print,” he wrote the next month. “Maybe Graham will go away, or become King of Man. I sent him details of my formula for making gold out of water,” he told Russell in June.

In between these quips, Thayer ran what seem to have been Graham’s other contributions, though the same caveats apply to these as did the first one. Doubt 43 (February 1954—note: published six months after Graham requested it) carried a story about a girl walking her baby sister in a pram who had an arm blown off when something fell from the sky; both the RAF and USAF, who were active in the area, denied any responsibility. Graham was not the only one to contribute the story—do did Helen Knothe and some unnamed others. The following issue, published in April 1954, carried a story about ancient lotus seeds from China that were being grown in Washington, D.C. (not the only time a story like this was reported in Doubt; Arrow Mackey contributed one, too.) In this case, Graham was singled out as a “non-member,” which may have been Thayer’s way of goosing him to pay his dues.

Graham’s last (extant) letter to Russell was dated September 1954, and encapsulated the entire correspondence. It’s also the only typewritten letter from him in Russell’s archives. He wrote,

“I presume that your society stands for an extreme communism that is for abolishing organised [sic] society, therefore you attack all institutions utilising [sic] Forts [sic] attack in order to destroy science.

“Presumably Forts [sic] intention was to destroy existing beliefs by writing books ridiculing scientists for sale among males and bring in his own twin main ideas of contact with other worlds, and psychic subjects.

“Thus your attack is intended to destroy all organised [sic] society for good.

“Forts[sic] attack was intended to destroy existing scientific ideas in order to introduce the new ideas he had formulated.

“Two entirely different aims, but that Mr thayer [sic] is using Fort for his own ends.

“Yours truly, J. Graham”

That was par for the course as far as criticism of the Society went. Thayer was often attacked for making Forteanism political. And being accused of communism was common enough—Thayer came to see accusations of being red just a way to hating on something, free of any specific complaint. The kicker came with the postscript: “P.S.—-I will buy DOUBT from you as the Micros Book Co dont [sic] now stock it, they told me.” So for all the criticism, all the venom, he was still going to keep buying the magazine, and even, perhaps, become a member.

There are a couple of reasons Graham may not have any letters in Russell’s archive after September 1954. One may be that Russell stopped saving them, sending them instead to the trash bin. Another may be that Russell found Graham a different correspondent. Thayer remarked that same month, “Mike Jenkinson is our second Venusian correspondent. Can’t you dig up on from Saturn for a change? Anyway, Graham’s schemes would work better on Venus, so you did well to knock their heads together.” I do not know who Mike Jenkinson was (the other Venusian correspondent was Frederick G. Hehr), but there may have been letters shared between Jenkinson and Graham. A third reason is that Graham found a different—but related—enthusiasm, and a different institution to write.

Graham was in correspondence with the Museum of Natural History in December of 1954, three months after the seeming end of his connection to Russell. (We know it’s the same Graham because the address is the same.) The first letter, which is not in the Museum’s archives, was apparently dated 7 December and regarded sonar readings from the “Rival III.” Graham wanted to know the Museum’s opinion. The answer to Graham, as it came down, was a cleaned up version of a memo written by Hampton Widman Parker, who called it “press nonsense.” Apparently Graham had called the sonar “radar,” and because Graham had not bothered reading the stories, he pointed out that radar could not detect shape—and it was claimed the “Rival” had limned the monster’s outline. F. C. Fraser, who composed the actual reply, added that he had no special knowledge of the equipment used, and so was reluctant to opine on the matter. (From correspondence in the same file, it seems that this was Fraser’s general policy: offering no opinion on the matter of the Loch Ness Monster.

Graham, as he had with Russell, replied quickly, and brought to bear more questions—and more material generally. He said that he had learned the radar—as he kept calling it—in this situation could detect an outline, and so again asked for the Museum’s opinion. He also brought up another recent discovery—a peculiar creature captured in a net recently off Dungeness. I have not heard of this episode—and a quick search turned up nothing—but Dungeness is in the southern part of England, on the English Channel. Again, he wanted the museum’s opinion of the matter. Finally, he noted that supposedly extinct species may survive in a number places around the globe. Enclosed with his letter were two drawings. One was a map that showed Inverness and Loch Ness; a blow-up section showed the “Rival” and its relative position to the supposed creature as well as the monster’s outline. The other was a world map, showing the location of the Loch Ness Monster, the “Snow-Man,” and where the coelacanth was re-discovered; the bottom half was a blow-up of southern England, with the notation of the Dungeness creatures discovery on 18 December and a line drawing of the sea monster.

Fraser wrote again a week later, on the 29th of December. This was the last letter in the correspondence or, at least, the last preserved in the Museum’s archives. It was a terse closure, only two sentences long. The first dispatched with the sea monster of southern England: “The fish caught at Dungeness was a young Basking Shark.” The second reiterated Fraser’s insistence on not discussing the Loch Ness Monster: “I regret that I am unable to express any opinion about the Loch Ness record.” (Note that he did not say “Monster.”) There was no mention of the maps or Graham’s interest in what was only sporadically being called cryptozoology.

Graham, though, was not done with Forteanism. Thayer still had him in mind. In December 1954, around the time that Graham was asking the museum about the Loch Ness Monster, Thayer quipped to Russell—making reference to personal events I do not know anything about— “I am beginning to feel Graham’s awful power. Twice, recently, the world has stood still, and no one but Graham could have caused that, except yourself, of course, and I’m fairly sure you would have told me.” And he must have continued to have some association with the Society—as a member or a purchaser of individual issues, supplier of materials, and dispenser of advice, I do not know.

In June 1957, Thayer wrote to Russell once more, repeating a joke that, in the absence of any other information, must stand as the epitaph for Graham’s Fortean career: “Graham is obviously the reincarnation of the talking mongoose.”