A surprisingly mainstream author and Fortean.

(At times, looking through the Forteans, I become so accustomed to investigating people on the fringes I am startled to see someone from the center be not only a Fortean but an enthusiastic one.)

John Alfred Atkins was born 26 May 1916 in Carshalton, Surrey. His father was an insurance agent; his mother would become a teacher. Apparently, he saw his father only rarely. He attended school in Suffolk and then graduated from Bristol University in 1938. He married in 1938. His wife was Joan Grey, an artist, and they would have two daughters. After graduation he went to work for Mass Observation, which was a giant social science project started the year before to record the daily life of Britons and also as an assistant editor for Tribune. (I am not sure if these jobs overlapped or were serial.) Thus began a career devoted to literature, both high and low, sacred and profane.

(At times, looking through the Forteans, I become so accustomed to investigating people on the fringes I am startled to see someone from the center be not only a Fortean but an enthusiastic one.)

John Alfred Atkins was born 26 May 1916 in Carshalton, Surrey. His father was an insurance agent; his mother would become a teacher. Apparently, he saw his father only rarely. He attended school in Suffolk and then graduated from Bristol University in 1938. He married in 1938. His wife was Joan Grey, an artist, and they would have two daughters. After graduation he went to work for Mass Observation, which was a giant social science project started the year before to record the daily life of Britons and also as an assistant editor for Tribune. (I am not sure if these jobs overlapped or were serial.) Thus began a career devoted to literature, both high and low, sacred and profane.

Tribune was a social democratic magazine also begun in 1937. The paper sought to develop a public that was anti-Fascist and anti-appeasement. In its early years, the furor that bubbled through left-leaning and communist groups worked its way through the magazine, too, and there was turn-over. Associated with the magazine was Victor Gollancz, who published Fort in England. After the Nazi-Soviet pact, the pro-Soviets on staff were either fired or quit, leaving Tribune as leftist but not communist. Atkins worked his way up to literary editor. He published a book of poetry in 1942 (The Experience of England) and a work of fiction the following year (The Diary of William Carpenter).

Atkins left in 1943—replaced by George Orwell—when it became clear that he would be called up for service. He worked for the Royal Artillery in Wales. By accounts, he did not get along with military discipline and would go AWOL for long stretches, though not so long as to be classed a deserter. In 1945, he stayed in a dilapidated building with Alfred Perlès, (who knew Henry Miller) and a few others of artistic temperament. He spent some time in detention. After VE Day, he was released from service.

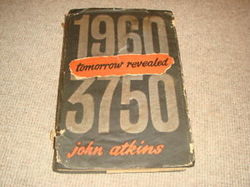

Left leaning, he became a teacher and organizer with the West Country Workers' Education Association, which was an adult education program aimed particularly at those who had missed out on school earlier in their lives. And he continued to involve himself in literary projects. He contributed to Penguin New Writing, a monthly publication devoted to anti-Fascist writing. In 1947, he published a study of the writer Walter de la Mare. He also published studies of Ernest Hemingway (1952), George Orwell (1954), science fiction (1955), Graham Greene (1957), Aldous Huxley (1968), sex in literature (four volumes, 1970-78), J. B. Priestly (1981), and the British Spy Novel (1984). In addition, he wrote the novels Cat on Hot Bricks (1950), Rain and the River (1953), and A Land For for ‘eros (1957).

As with many writers, Atkins could not support himself with book publishing (and perhaps his idealism led him to continue to work, too). Through most of the 1950s and 1960s he worked as teacher in Sudan. This period witnessed the end of England’s rule in that country, its transition and early independence marked by political and economic difficulties. (One thinks of the ex-patriates in Morocco at around the same time, Paul Bowles, the Forteans William Burroughs and E. Guillan Hopper, among others, experiencing a similar transition.) Atkins was there from 1951 to 1955 (the latter was the year that saw Sudanese independence) and again from 1958 to 1968 (when the government was particularly unstable, setting the stage for a 1969 coup). He moved to Libya for two years (1968-1970) and then Poland (1970-76). He finally returned to England then. His wife passed in 1993.

John Alfred Atkins died 31 March 2009, aged 92.

*********************************

When Atkins discovered Fort is not known, but he knew of both the man and the Society by the middle of 1947 well enough to approach Thayer for an article about recent advances in Forteanism which he wanted to publish in his magazine, Albion. This bit of information comes from a letter Atkins wrote to Eric Frank Russell in June. Thayer said he’d get around to the article when he could, but also suggested Atkins approach Russell, though Atkins was not clear why, or who would be writing the article. Russell went ahead and put together a piece on Forteanism in England, but Thayer does not seem to have ever completed his part, and so Russell’s did not run.

At the time, Atkins said in a July letter, he was calling himself “an unofficial Fortean . . . because although I have his tok and am heartily sick of orthodox scientific dogma and intellectual restraint, I am not a member of the society.” But he was ready to join. Which he did in August, after Russell told him how to convert the dues and to whom to send them. With his subscription, he also sent in three clippings and continued to press for an article on Fort for “Albion.” From the 6 August letter: “I know that your article would not require any introduction in the normal way, but I want to introduce the Fortean Society and its work to my readers, which is a different thing. In the ordinary newspaper or magazine such an article would get in on interest value alone, but Albion is not that kind, being a literary magazine with a limited public. I have come across so many intelligent and quite wideawake [sic] people who have never heard of Fort or at least know nothing of him that I want to remedy the deficiency in the small way open to me. Therefore I want to say who Fort was and what he did and then print your article as an example of Fortean research and speculation. But I agree there is no need for the article itself to be altered—it is just a case of putting it in its context.”

Atkins continued to write frequently, sending later in the month a copy of Albion for Russell’s perusal and a passage copied out from a book by the elder Dumas. Apparently, Russell passed on a copy of (MFS) Lilith Lorraine’s poetry magazine “Different.” In September, Atkins sent along another clipping and remarked that he was interested in setting up an exchange with Lorraine, though he wasn’t exactly excited by the poetry he saw here printing. (He admitted he had not made a study of the magazine yet.) Also apparently—only letters from Atkins exist—Russell had suggested that Atkins start a fantasy magazine. This was a period when English fandom was just recovering from World War II and starting a few ‘zines and professional magazines. Atkins like the idea, but couldn’t see brining it off: the publishers of his own magazine had suspended their work, and Albion itself was dying on the vine. He was negotiating with other publishers, but didn’t feel he had many contacts and thought the whole industry in a very tenuous state.

After the initial rush of infatuation, the correspondence between Russell and Atkins slowed quite a bit. In time, it came to reflect the conversations the Thayer and Russell had about Atkins in their own correspondence. To wit, almost all of it was about money: money for books, money for dues. Atkins purchased some of the pamphlets on the Drayson problem; he bought “Errors of Thought”; he bought “Ego and His Own.” Usually, he was slow paying, complaining a bit about what he thought were exorbitant prices, but paying nonetheless. He was slow about paying his dues in the 1950s, too, perhaps because, as he told Russell, he wasn’t receiving Doubt very regularly. Thayer liked Atkins (“a dear”), and extended him a long line of credit, as he did most Forteans, and especially those in other countries. When the British currency was devalued, he allowed Atkins and others to keep paying at the old exchange rate.

Atkins appeared three times in Doubt between his initial signs of interest and 1950. The first was material—otherwise unknown—that Thayer included in a round-up of English happenings (“Tight Isle,” Doubt 20, March 1948). The second was a letter—Doubt 26, October 1949—about curious stones he had picked up in Wales; they had been found after a storm, and reported by a newspaper in 1939. He was trying to track down more information on them. He sent a picture, but the poor quality of the reproduction makes it impossible to tell why these stones were curious. (The letter, though, seems to have been part of an on-going conversation with Thayer, meaning they had a correspondence, too, now lost.) The third mention, in Doubt 29, July 1950, merely noted he had sent in clippings which were not used.

Around 1950—the exact date unknown—Atkins published an article on Fort. It was in a (very) small literary magazine “The Glass,” which was handprinted by another Fortean, Antony Borrow.” According to the introduction, “The Glass” was devoted to “such forms as Fable, Fantasy, Poetry, Prose-Poetry, Journals, and other genres of imaginative and introspective writing.” It was the fourth issue of the magazine. The back pages was a standard ad for the omnibus edition of Charles Fort’s books plus a list of shops that could provide it in the UK. Likely, the ad ran in other issues, too, given Borrow’s own connection to the Society.

Atkins’s article, “The Challenge of Charles Fort,” lead off the issue. And it started off with an anecdote that explained the enigmatic stones from Doubt: “During the war I went into a Welsh pub and my eye was immediately taken by a curious object on a stand in the hall. It was a block of smooth black material, very hard, about the size of today’s joint for a family of six. The interesting thing about it was that it was incised very deeply with regular yet unfamiliar characters. My immediate reaction was: Obviously man-made and no natural freak. On the wall was a framed cutting saying that this object and others like it had been picked up in the neighborhood after a violent thunder storm during there last century. The implication was that, even if it was not a meteorite, it was some product of meteorological disturbance.”

He went on then to connect his own attitude, and similar reactions to Charles Fort: “Such an explanation just was not acceptable. Or rather, I should say, was too unlikely to be accepted. The difference between the two attitudes is extremely germane to a consideration of Charles Fort’s research and philosophy.

“Some such occurrence as this must have set Fort off on his enquiry. He was obviously, by nature, a sceptic. But there were many fields in which he could have indulged his skepticism without challenging the whole basis of science as practised today.

“Returning to my Welsh ‘stone’, there are many questions Fort would have asked. (Bear in mind that it is not an isolated instance but that many other equally mysterious objects have suddenly appearance [sic] on this earth.) Why have the meteorologists been so satisfied with an answer that will not hold water? Why are they so wedded to the belief that things falling from the sky must have come originally from another part of our world, Tellus? Or why do they fall back on that convenient little Phenomenon, the meteorite, with such relief? Why are they so reluctant to embark on research into the origins of these unassimilated strangers?”

Atkins then went on to give a quick description of Fort’s work—it derived from these questions, he said, and had him collecting his clippings on the anomalous. (As far as I know, there’s no evidence that Atkin’s reconstruction of Fort’s thought is correct. His biographers have not answered whether he started collecting, then asked the questions, or asked the questions, then started collecting.) The paragraph culminates in a listing of Fort’s four books, which Atkins sees as a mingling of old wive’s tales and metaphysical conclusions.

Which isn’t to say that he doesn’t accept the facts Fort puts forward—he sees the research as important—but is more taken by the ‘tentative conclusions’ and the slap they give to positivism. Fort was playful, offering conclusions just as logical as the ones offered by scientists, but opening rather than closing future thought, Atkins said, neither believing them nor disbelieving them. “We live in the decadence of science. Scientists have established a world picture which they cling to as fiercely as the schoolmen clung to their ninth heaven. If a fact cannot be assimilated it is excluded, usually by ridicule, though increasingly by an appeal to hypnosis. But just as mediaeval metaphysics gave way to modern positivism, so must the later give way to what Fort terms Intermediatism.”

Atkins diverged for a second, bringing in Dante (!) to explain the difference between mediaevalists and modernists—in both cases, the evidence of the senses being denied—before returning to Fort and his suggestion that belief—which Atkins associated with decadent science—by replaced by acceptance. “His argument is that if there are rival hypotheses the sensible thing to two is to accept both until one is disproved. We have a good illustration of this in the interpretation of dreams,” Atkins went on, pointing to the different hermeneutics employed by Freudians and those who followed Dunne.

This reading probably pinned Fort down more than he would have preferred while simultaneously leaving the door open for science to have the final say—in that scientists would determine what counted as disproved. Fort was both offering his ideas as contrary to science and not willing offering them, but in either case was not content to let scientists have the last word. Or, perhaps, any word, anymore. But Atkins read Fort as a kind of pluralist (completely ignoring the material monism that underlay his ideas): “J.C. Powys says that Rabelais, like Walt Whitman, seemed prepared to believe anything except that there is only one truth to be believed—and this Fort would call acceptance . . . But no man stands alone. I believe that, in his psychopathic embrace, Henry Miller has given a Fortean shove to literary expression.”

And that is a very acute thing to say, however much he may have been reading Fort selectively. Powys and Miller were both fans of Fort, Powys one of the founders of the Fortean Society. Rabelais was a favorite of Tiffany Thayer. And Walt Whitman inspired many off the poets who were, admittedly a bit distantly, connected to Fort. These were writers unwilling to be hemmed in by convention, forced to accept the reasonable, writers on the look out for new ways of seeing the universe by paying attention to what was ignored, what was damned. It would have been a worthy conclusion to the article.

But for whatever reason, Atkins felt the need to append one more bit: perhaps it was all too theoretical, not rooted in anomalous phenomena. And so he made reference to a woman in Washington who, in January 1948, claimed to see a winged man fly over her barn. What could be the explanation, Atkins wondered: Inebriation? Senility? Insanity? Imagination? He knew what scientists would say. But Fort would refuse judgment because “the woman was there and he wasn’t.” Which isn’t exactly true—Fort very well might have accepted it and used it to spin out some theory. More to the point, refusing judgment is different than acceptance. The confusion shows that Atkins did not have a firm grasp on what it meant to be a Fortean, but rather a general approach: science, sure, but what else?

Whatever else might be confused about his Fortean philosophy, it is clear that Atkins understood the playfulness. He seems to have been something of a playful thinker himself. He next appeared in Doubt 31 (January 1951), showing off his waggishness. There had been reports of weirdly colored skies all over Scotland recently. Atkins wrote in to Thayer that he had approached a medium and gotten in contact with Fort’s spirit—an obvious joke—and the Fort had cracked that the most “impressive thing here is that astronomers saw” the anomaly. Usually, there eyes were closed to such things. But he had a prediction for how they would get out of the mess. There would be a volcanic explosion in a few months, and the astronomers could explain the off colors that way. Thayer was always pointing out that official explanations relied on events that came after the original anomaly; this would be another such case.

Perhaps what drew Atkins to Fort was an interest i astronomical events. At least, Atkins seemed inordinately fond of such phenomena. He was credited in Doubt 32 (March 1951) with sending in something about objects falling from the sky (his exact contribution cannot be tracked). Again in Doubt 59 (January 1959)—Atkins final appearance in the magazine, two issues before it ended its run with Thayer’s death—he was credited with sending in a clipping on unusual items falling from the sky, and again the specific clipping could not be attached to him. In between, he sent Thayer reports of “black moons” in Syria (Doubt 37, June 1952).

The other clippings he sent that made the grade in Doubt also stay within a limited range of interests. Two others involve the appearance and disappearance of unusual objects. In Doubt 32 (March 1951) he was credited, alongside several other Forteans, with sending in clippings that showed the disappearance of the Stone of Scone—the traditional coronation place for monarchs of Scotland—occurred at about the same time the statue of Britannia in Waterloo Palace was relieved of a 4-foot long bronze sword. In 1957—Doubt 53, February—Atkins reported he had found a bit of China in his yard after a gale; he had worked the land a lot, so it had to be new. The piece was a ceramic replica of two birds on a bough. (He sent Thayer a picture.) “Where did these birds come from? I think it unlikely that anyone started throwing bits of China into my garden in the midst of a storm.”

The last of his contributions to Doubt plumped for his pluralism and a more active Fortean Society. From Doubt 36 (April 1952):

“Some time ago I asked for a series of articles on minority theories which you agreed to and very sensibly referred to as the Black Earth and Flat Magic Programme. I have a feeling that the Society should move on to a new phase of activity or propaganda. So far its method has been destruction of unproved certainties. Our civilization has adopted one particular picture of the universe out of many possibles, and all forces of science, religion and government are used to assert its truth. I am not asking for any positive programme because, as you say, we mustn’t go against our natures--but let’s hear some of the other pictures of the universe that are held and have been held. I think we ought to be a little more positive than we are--never, of course, saying that the answer is such-and-such but that it might be of that it might be one of many possibilities. I really think that our job is to show that the picture of the universe that has been established might just as well be false as true--and indicate some of the pictures that have been veiled--including the interesting mediavel [sic] one, or elements of it. What do you think?”

Thayer apparently did not think much of the idea, as he did not think much of Atkins’s ideas in general. He may have liked him—though this was leavened with some suspicion; once he asked Russell if he had ever met Atkins and what his opinion was—but he didn’t go along with Atkins’s brand of Forteanism. He didn’t use all (or most? or any?) of Atkins’s early clippings, or at least did not give him credit. The China Atkins found, Thayer wrote in Doubt, was “probably mundane.” (Admittedly, this remark was ambiguous and may have referred to the quality of the art.) Thayer was not sure why Atkins moved to Sudan, and suggested to Russell it was likely some advanced guard for England’s political interests—which seemed prophetic when England did send soldiers there.

Mostly, though, Thayer did not seem to like his astronomical reports. Judging by what Thayer wrote in his letters, there were many more reports of ‘black moons.’ At the same time, Atkins did not have anything negative (or anomalous) to report about an eclipse in Sudan, and Thayer was always on the look out for reports about eclipses that called into question Einstein’s theories. The black moons Thayer dismissed out of hand. He told Russell, in 1953, “Atkins is queer for those black moons in Sudan. ‘It’s mammy palaver, you goddam fool, mammy-palaver.’” I’m not sure what—if anything—Thayer i quoting, but his opinion is clear. Mammy-palaver was a racist way of referring to old-wives tales of blacks.

The other connection Atkins had to Forteans was via science fiction. Interestingly, though, his book on science fiction makes no reference to Fort, even though Eric Frank Russell’s Sinister Barrier plays an important part. Perhaps the absence stems from the structure of the book; perhaps from the other writers he mostly considered. Atkins playfully wrote his summa of science fiction as if he were a historian of the far-future, trying to piece together the past. In this post-apocalyptic world, knowledge is hard to come by, and he takes science fiction as history, though distorted for ideological reasons, and strings together the tales of Wells and Orwell and Russell and many others—mostly, though not exclusively, British—into a history that extends for hundreds of years beyond the 20th century, making alien invasions and nuclear attacks real events. Such a reconstruction had little room for Fort’s skepticism; and most of these authors had little contact with Fort—indeed, Wells was decidedly an anti-Fortean.

As far as I can tell, Atkins’s Forteanism did not receive public display after the end of the Society; that also seems to have ended his contact with Russell. For a time, though, he was offering an interesting take on Fort and his ideas, though they were suggestions that did not hold much sway in the larger Fortean community.

Atkins left in 1943—replaced by George Orwell—when it became clear that he would be called up for service. He worked for the Royal Artillery in Wales. By accounts, he did not get along with military discipline and would go AWOL for long stretches, though not so long as to be classed a deserter. In 1945, he stayed in a dilapidated building with Alfred Perlès, (who knew Henry Miller) and a few others of artistic temperament. He spent some time in detention. After VE Day, he was released from service.

Left leaning, he became a teacher and organizer with the West Country Workers' Education Association, which was an adult education program aimed particularly at those who had missed out on school earlier in their lives. And he continued to involve himself in literary projects. He contributed to Penguin New Writing, a monthly publication devoted to anti-Fascist writing. In 1947, he published a study of the writer Walter de la Mare. He also published studies of Ernest Hemingway (1952), George Orwell (1954), science fiction (1955), Graham Greene (1957), Aldous Huxley (1968), sex in literature (four volumes, 1970-78), J. B. Priestly (1981), and the British Spy Novel (1984). In addition, he wrote the novels Cat on Hot Bricks (1950), Rain and the River (1953), and A Land For for ‘eros (1957).

As with many writers, Atkins could not support himself with book publishing (and perhaps his idealism led him to continue to work, too). Through most of the 1950s and 1960s he worked as teacher in Sudan. This period witnessed the end of England’s rule in that country, its transition and early independence marked by political and economic difficulties. (One thinks of the ex-patriates in Morocco at around the same time, Paul Bowles, the Forteans William Burroughs and E. Guillan Hopper, among others, experiencing a similar transition.) Atkins was there from 1951 to 1955 (the latter was the year that saw Sudanese independence) and again from 1958 to 1968 (when the government was particularly unstable, setting the stage for a 1969 coup). He moved to Libya for two years (1968-1970) and then Poland (1970-76). He finally returned to England then. His wife passed in 1993.

John Alfred Atkins died 31 March 2009, aged 92.

*********************************

When Atkins discovered Fort is not known, but he knew of both the man and the Society by the middle of 1947 well enough to approach Thayer for an article about recent advances in Forteanism which he wanted to publish in his magazine, Albion. This bit of information comes from a letter Atkins wrote to Eric Frank Russell in June. Thayer said he’d get around to the article when he could, but also suggested Atkins approach Russell, though Atkins was not clear why, or who would be writing the article. Russell went ahead and put together a piece on Forteanism in England, but Thayer does not seem to have ever completed his part, and so Russell’s did not run.

At the time, Atkins said in a July letter, he was calling himself “an unofficial Fortean . . . because although I have his tok and am heartily sick of orthodox scientific dogma and intellectual restraint, I am not a member of the society.” But he was ready to join. Which he did in August, after Russell told him how to convert the dues and to whom to send them. With his subscription, he also sent in three clippings and continued to press for an article on Fort for “Albion.” From the 6 August letter: “I know that your article would not require any introduction in the normal way, but I want to introduce the Fortean Society and its work to my readers, which is a different thing. In the ordinary newspaper or magazine such an article would get in on interest value alone, but Albion is not that kind, being a literary magazine with a limited public. I have come across so many intelligent and quite wideawake [sic] people who have never heard of Fort or at least know nothing of him that I want to remedy the deficiency in the small way open to me. Therefore I want to say who Fort was and what he did and then print your article as an example of Fortean research and speculation. But I agree there is no need for the article itself to be altered—it is just a case of putting it in its context.”

Atkins continued to write frequently, sending later in the month a copy of Albion for Russell’s perusal and a passage copied out from a book by the elder Dumas. Apparently, Russell passed on a copy of (MFS) Lilith Lorraine’s poetry magazine “Different.” In September, Atkins sent along another clipping and remarked that he was interested in setting up an exchange with Lorraine, though he wasn’t exactly excited by the poetry he saw here printing. (He admitted he had not made a study of the magazine yet.) Also apparently—only letters from Atkins exist—Russell had suggested that Atkins start a fantasy magazine. This was a period when English fandom was just recovering from World War II and starting a few ‘zines and professional magazines. Atkins like the idea, but couldn’t see brining it off: the publishers of his own magazine had suspended their work, and Albion itself was dying on the vine. He was negotiating with other publishers, but didn’t feel he had many contacts and thought the whole industry in a very tenuous state.

After the initial rush of infatuation, the correspondence between Russell and Atkins slowed quite a bit. In time, it came to reflect the conversations the Thayer and Russell had about Atkins in their own correspondence. To wit, almost all of it was about money: money for books, money for dues. Atkins purchased some of the pamphlets on the Drayson problem; he bought “Errors of Thought”; he bought “Ego and His Own.” Usually, he was slow paying, complaining a bit about what he thought were exorbitant prices, but paying nonetheless. He was slow about paying his dues in the 1950s, too, perhaps because, as he told Russell, he wasn’t receiving Doubt very regularly. Thayer liked Atkins (“a dear”), and extended him a long line of credit, as he did most Forteans, and especially those in other countries. When the British currency was devalued, he allowed Atkins and others to keep paying at the old exchange rate.

Atkins appeared three times in Doubt between his initial signs of interest and 1950. The first was material—otherwise unknown—that Thayer included in a round-up of English happenings (“Tight Isle,” Doubt 20, March 1948). The second was a letter—Doubt 26, October 1949—about curious stones he had picked up in Wales; they had been found after a storm, and reported by a newspaper in 1939. He was trying to track down more information on them. He sent a picture, but the poor quality of the reproduction makes it impossible to tell why these stones were curious. (The letter, though, seems to have been part of an on-going conversation with Thayer, meaning they had a correspondence, too, now lost.) The third mention, in Doubt 29, July 1950, merely noted he had sent in clippings which were not used.

Around 1950—the exact date unknown—Atkins published an article on Fort. It was in a (very) small literary magazine “The Glass,” which was handprinted by another Fortean, Antony Borrow.” According to the introduction, “The Glass” was devoted to “such forms as Fable, Fantasy, Poetry, Prose-Poetry, Journals, and other genres of imaginative and introspective writing.” It was the fourth issue of the magazine. The back pages was a standard ad for the omnibus edition of Charles Fort’s books plus a list of shops that could provide it in the UK. Likely, the ad ran in other issues, too, given Borrow’s own connection to the Society.

Atkins’s article, “The Challenge of Charles Fort,” lead off the issue. And it started off with an anecdote that explained the enigmatic stones from Doubt: “During the war I went into a Welsh pub and my eye was immediately taken by a curious object on a stand in the hall. It was a block of smooth black material, very hard, about the size of today’s joint for a family of six. The interesting thing about it was that it was incised very deeply with regular yet unfamiliar characters. My immediate reaction was: Obviously man-made and no natural freak. On the wall was a framed cutting saying that this object and others like it had been picked up in the neighborhood after a violent thunder storm during there last century. The implication was that, even if it was not a meteorite, it was some product of meteorological disturbance.”

He went on then to connect his own attitude, and similar reactions to Charles Fort: “Such an explanation just was not acceptable. Or rather, I should say, was too unlikely to be accepted. The difference between the two attitudes is extremely germane to a consideration of Charles Fort’s research and philosophy.

“Some such occurrence as this must have set Fort off on his enquiry. He was obviously, by nature, a sceptic. But there were many fields in which he could have indulged his skepticism without challenging the whole basis of science as practised today.

“Returning to my Welsh ‘stone’, there are many questions Fort would have asked. (Bear in mind that it is not an isolated instance but that many other equally mysterious objects have suddenly appearance [sic] on this earth.) Why have the meteorologists been so satisfied with an answer that will not hold water? Why are they so wedded to the belief that things falling from the sky must have come originally from another part of our world, Tellus? Or why do they fall back on that convenient little Phenomenon, the meteorite, with such relief? Why are they so reluctant to embark on research into the origins of these unassimilated strangers?”

Atkins then went on to give a quick description of Fort’s work—it derived from these questions, he said, and had him collecting his clippings on the anomalous. (As far as I know, there’s no evidence that Atkin’s reconstruction of Fort’s thought is correct. His biographers have not answered whether he started collecting, then asked the questions, or asked the questions, then started collecting.) The paragraph culminates in a listing of Fort’s four books, which Atkins sees as a mingling of old wive’s tales and metaphysical conclusions.

Which isn’t to say that he doesn’t accept the facts Fort puts forward—he sees the research as important—but is more taken by the ‘tentative conclusions’ and the slap they give to positivism. Fort was playful, offering conclusions just as logical as the ones offered by scientists, but opening rather than closing future thought, Atkins said, neither believing them nor disbelieving them. “We live in the decadence of science. Scientists have established a world picture which they cling to as fiercely as the schoolmen clung to their ninth heaven. If a fact cannot be assimilated it is excluded, usually by ridicule, though increasingly by an appeal to hypnosis. But just as mediaeval metaphysics gave way to modern positivism, so must the later give way to what Fort terms Intermediatism.”

Atkins diverged for a second, bringing in Dante (!) to explain the difference between mediaevalists and modernists—in both cases, the evidence of the senses being denied—before returning to Fort and his suggestion that belief—which Atkins associated with decadent science—by replaced by acceptance. “His argument is that if there are rival hypotheses the sensible thing to two is to accept both until one is disproved. We have a good illustration of this in the interpretation of dreams,” Atkins went on, pointing to the different hermeneutics employed by Freudians and those who followed Dunne.

This reading probably pinned Fort down more than he would have preferred while simultaneously leaving the door open for science to have the final say—in that scientists would determine what counted as disproved. Fort was both offering his ideas as contrary to science and not willing offering them, but in either case was not content to let scientists have the last word. Or, perhaps, any word, anymore. But Atkins read Fort as a kind of pluralist (completely ignoring the material monism that underlay his ideas): “J.C. Powys says that Rabelais, like Walt Whitman, seemed prepared to believe anything except that there is only one truth to be believed—and this Fort would call acceptance . . . But no man stands alone. I believe that, in his psychopathic embrace, Henry Miller has given a Fortean shove to literary expression.”

And that is a very acute thing to say, however much he may have been reading Fort selectively. Powys and Miller were both fans of Fort, Powys one of the founders of the Fortean Society. Rabelais was a favorite of Tiffany Thayer. And Walt Whitman inspired many off the poets who were, admittedly a bit distantly, connected to Fort. These were writers unwilling to be hemmed in by convention, forced to accept the reasonable, writers on the look out for new ways of seeing the universe by paying attention to what was ignored, what was damned. It would have been a worthy conclusion to the article.

But for whatever reason, Atkins felt the need to append one more bit: perhaps it was all too theoretical, not rooted in anomalous phenomena. And so he made reference to a woman in Washington who, in January 1948, claimed to see a winged man fly over her barn. What could be the explanation, Atkins wondered: Inebriation? Senility? Insanity? Imagination? He knew what scientists would say. But Fort would refuse judgment because “the woman was there and he wasn’t.” Which isn’t exactly true—Fort very well might have accepted it and used it to spin out some theory. More to the point, refusing judgment is different than acceptance. The confusion shows that Atkins did not have a firm grasp on what it meant to be a Fortean, but rather a general approach: science, sure, but what else?

Whatever else might be confused about his Fortean philosophy, it is clear that Atkins understood the playfulness. He seems to have been something of a playful thinker himself. He next appeared in Doubt 31 (January 1951), showing off his waggishness. There had been reports of weirdly colored skies all over Scotland recently. Atkins wrote in to Thayer that he had approached a medium and gotten in contact with Fort’s spirit—an obvious joke—and the Fort had cracked that the most “impressive thing here is that astronomers saw” the anomaly. Usually, there eyes were closed to such things. But he had a prediction for how they would get out of the mess. There would be a volcanic explosion in a few months, and the astronomers could explain the off colors that way. Thayer was always pointing out that official explanations relied on events that came after the original anomaly; this would be another such case.

Perhaps what drew Atkins to Fort was an interest i astronomical events. At least, Atkins seemed inordinately fond of such phenomena. He was credited in Doubt 32 (March 1951) with sending in something about objects falling from the sky (his exact contribution cannot be tracked). Again in Doubt 59 (January 1959)—Atkins final appearance in the magazine, two issues before it ended its run with Thayer’s death—he was credited with sending in a clipping on unusual items falling from the sky, and again the specific clipping could not be attached to him. In between, he sent Thayer reports of “black moons” in Syria (Doubt 37, June 1952).

The other clippings he sent that made the grade in Doubt also stay within a limited range of interests. Two others involve the appearance and disappearance of unusual objects. In Doubt 32 (March 1951) he was credited, alongside several other Forteans, with sending in clippings that showed the disappearance of the Stone of Scone—the traditional coronation place for monarchs of Scotland—occurred at about the same time the statue of Britannia in Waterloo Palace was relieved of a 4-foot long bronze sword. In 1957—Doubt 53, February—Atkins reported he had found a bit of China in his yard after a gale; he had worked the land a lot, so it had to be new. The piece was a ceramic replica of two birds on a bough. (He sent Thayer a picture.) “Where did these birds come from? I think it unlikely that anyone started throwing bits of China into my garden in the midst of a storm.”

The last of his contributions to Doubt plumped for his pluralism and a more active Fortean Society. From Doubt 36 (April 1952):

“Some time ago I asked for a series of articles on minority theories which you agreed to and very sensibly referred to as the Black Earth and Flat Magic Programme. I have a feeling that the Society should move on to a new phase of activity or propaganda. So far its method has been destruction of unproved certainties. Our civilization has adopted one particular picture of the universe out of many possibles, and all forces of science, religion and government are used to assert its truth. I am not asking for any positive programme because, as you say, we mustn’t go against our natures--but let’s hear some of the other pictures of the universe that are held and have been held. I think we ought to be a little more positive than we are--never, of course, saying that the answer is such-and-such but that it might be of that it might be one of many possibilities. I really think that our job is to show that the picture of the universe that has been established might just as well be false as true--and indicate some of the pictures that have been veiled--including the interesting mediavel [sic] one, or elements of it. What do you think?”

Thayer apparently did not think much of the idea, as he did not think much of Atkins’s ideas in general. He may have liked him—though this was leavened with some suspicion; once he asked Russell if he had ever met Atkins and what his opinion was—but he didn’t go along with Atkins’s brand of Forteanism. He didn’t use all (or most? or any?) of Atkins’s early clippings, or at least did not give him credit. The China Atkins found, Thayer wrote in Doubt, was “probably mundane.” (Admittedly, this remark was ambiguous and may have referred to the quality of the art.) Thayer was not sure why Atkins moved to Sudan, and suggested to Russell it was likely some advanced guard for England’s political interests—which seemed prophetic when England did send soldiers there.

Mostly, though, Thayer did not seem to like his astronomical reports. Judging by what Thayer wrote in his letters, there were many more reports of ‘black moons.’ At the same time, Atkins did not have anything negative (or anomalous) to report about an eclipse in Sudan, and Thayer was always on the look out for reports about eclipses that called into question Einstein’s theories. The black moons Thayer dismissed out of hand. He told Russell, in 1953, “Atkins is queer for those black moons in Sudan. ‘It’s mammy palaver, you goddam fool, mammy-palaver.’” I’m not sure what—if anything—Thayer i quoting, but his opinion is clear. Mammy-palaver was a racist way of referring to old-wives tales of blacks.

The other connection Atkins had to Forteans was via science fiction. Interestingly, though, his book on science fiction makes no reference to Fort, even though Eric Frank Russell’s Sinister Barrier plays an important part. Perhaps the absence stems from the structure of the book; perhaps from the other writers he mostly considered. Atkins playfully wrote his summa of science fiction as if he were a historian of the far-future, trying to piece together the past. In this post-apocalyptic world, knowledge is hard to come by, and he takes science fiction as history, though distorted for ideological reasons, and strings together the tales of Wells and Orwell and Russell and many others—mostly, though not exclusively, British—into a history that extends for hundreds of years beyond the 20th century, making alien invasions and nuclear attacks real events. Such a reconstruction had little room for Fort’s skepticism; and most of these authors had little contact with Fort—indeed, Wells was decidedly an anti-Fortean.

As far as I can tell, Atkins’s Forteanism did not receive public display after the end of the Society; that also seems to have ended his contact with Russell. For a time, though, he was offering an interesting take on Fort and his ideas, though they were suggestions that did not hold much sway in the larger Fortean community.