James Blish was a lapsed Fortean—which helps to make sense of his Forteanism.

There are lots of reasons various people were drawn to the works of Charles Fort, as has been shown through these biographies, and some of them can be grouped into families: those who search for something simultaneously material and transcendent, beyond science; those who have trouble with authorities; those who wish to put forth an alternative science. One type not yet explored—but well represented among the Forteans—is the person who wants to be the smartest in the room. Tiffany Thayer himself fits into this mold in many ways. And so does James Blish.

(I’ll have to say that, when I am not careful, I fall into this category trap, as well.)

Forteanism, used in this sense, allows the proponent to set themselves as smarter, more wise, than scientists, who are supposed to be the very embodiment of genius and rationality. The Fortean sees what the scientists does not. But this quest to be uniquely intelligent, to know more than everyone else, also tempts one to turn on Forteanism: for the Forteans, too, come to celebrate a particular body of knowledge. And the smartest person in the room will always see the problems with that body of knowledge, too. James Blish followed this path, embracing Fort and Forteanism, then turning on it.

At least that’s how I see Blish, although there are two necessary caveats. The first is obvious—this perspective is grounded in the facts of Blish’s life but is fully informed by my own ideas and biases. I am trying to animate his thought, and others might read Blish very differently. Second, although it has taken me a long time to put together this piece on Blish, I still haven’t seen everything of probable importance.

Unfortunately, most of his correspondence with Tiffany Thayer was destroyed in a flood. Also, Blish seems to have dealt—somewhat—with Fort in in amateur publication Tumbils, and I have not been able to see these yet. (Some are at U.C. Riverside). Finally, in correspondence Blish references an early essay on Fort, and I am still looking for it.

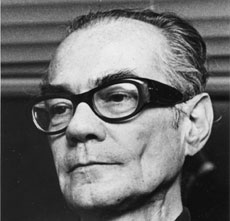

Blish was born 23 May 1921 in East Orange, NJ—making him eighteen years younger than Thayer and a member of a later generation of Forteans. (He was born two years after Fort’s first book, and was 11 years old when Fort died.) His father was in advertising. Damon Knight, a friend and fellow science fiction author, wrote, “Asa Blish came from a New England family; the name is a variant of Bliss. He was a publicist in the thirties for Bernarr MacFadden and for Arnold Gingrich of Esquire.

When James was six, his mother and father divorced—about the same age as Thayer was when his parent’s divorced—and Blish lived with his mother Dorothea. She was a piano teacher and Christian Scientist, but although Blish later developed an intense interest in music, he does not seem to have picked it up from her. David Ketterer, Blish’s biographer, makes clear that Blish had a very rocky relationship with his mother and seems to have resented her for most of his life.

In 1930, at the age of nine, Blish and his mother were living in Chicago with his maternal grandparents, The Schneewinds. Blish claimed (according to Knight) to be “some fractional part” Jewish on his mother’s side; “his maternal grandfather, Benjamin von Schneewind, was a candy manufacturer who packaged two large boxes of chocolates, very popular in the Midwest at one time, named the Dorothea and Babette Selections after his two daughters.” Also in the family home was a divorced uncle, who was the only one listed by the census as employed. He was a grain broker.

It was around this time—age nine—that Blish discovered science fiction. (When was the Golden Age of science fiction, goes the old saw: at age 12. So Blish was precocious.) A friend gave him the April 1931 issue of Astounding Stories. Sometime in the 1930s, Dorothea and Blish moved back to East Orange, where Dorothea made a living teaching piano. They struggled financially. Blish remained fascinated by science fiction. In 1935, only fourteen years old, he published a fanzine, “The Planeteer,” putting out six issues into 1936. Ketterer suggests that Blish got the idea from a letter in that issue of Astounding, written by Donald Wollheim, which proposed a magazine by that name.

Blish’s return to East Orange brought him in close contact with some active science fiction fans, as his “The Planeteer” indicates. He was writing stories for that magazine, and also publishing works in it by other science fiction writers, Edmund Hamilton and Lawrence Manning. In addition, he was a member of the Science Fiction Advancement Association (née International Cosmos Science Club), writing for its fanzine Tesseract. Eventually he was forced out of the SFAA over a small debt—such petty clashes were common in science fiction fandom—but he also became associated with the famous Futurians, which included Isaac Asimov, Wollheim, Knight, and others. In 1940, his first professional story appeared: “Emergency Refueling” in Super Science Stories.

Blish did not do much with The Futurians at first, as he entered Rutgers University in 1938, which occupied his time. He graduated in 1942 with a degree in zoology, and worked a little as an architect before enlisting in the army on 1 August 1942. He was 21 years old, 5’9” and a very slight 115 pounds. Damon Knight recounts, Blish “did not take well to military discipline; he was always in trouble over unsigned shoes, or pajamas showing under his trousers at reveille.” He refused an order to clean a grease trap and his father pulled strings to get him discharged. The Futurians welcomed his release from the military with a dinner at the Dragon Inn, in Greenwich Village.

It was in the post-military years that Blish became intensely involved with The Futurians. He befriended Knight, roomed with Robert Lowndes and, in 1947, married Virginia Kidd. He attended Columbia University from 1944 to 1946 first doing graduate work in limnology, then moving to literature, although he left college before completing his Master’s. The Futurians were young, leftish to various degrees, poor, and Bohemian: there were sexual affairs between them, and plenty of drinking. Blish published a little magazine, Rernascence, for a couple of years before moving on to “Tumbrils.” He became involved with the Vanguard Amateur Publishing Association, worked at the Scott Meredith Literary Agency as a reader, and continued to write—not only science fiction but all manner of pulp stories. Eventually, he went to work editing and writing for food and drug trade magazines. He and Virginia had little money.

Blish had a lot of enthusiasms, though. In 1956, Knight wrote,

“James Blish is an intense young man with a brilliant scholastic mind and an astonishing variety of enthusiasms—e.g., music, beer, astronomy, poetry, philosophy, cats. Until fairly recently he played two instruments and composed music; he still writes poetry and criticism for the little magazines, is a genuine authority on James Joyce and Ezra Pound, and an expert in half a dozen other fields. In college he was well on his way to becoming a limnobiologist when he discovered he was getting more A’s in English literature—and selling the stories he submitted to such magazines as Future, Cosmic and Super Science.

“One man is obviously not enough for all this, and there are really two Blishes: the alertly interested, warmly outgoing human being, and the cold, waspishly precise scholast. Up till now, in his prose work at least, I think the two have always got in each other’s way; Blish’s early stories are almost oppressively devoid of any human color or feeling; they might be stories written by an exceptionally able Martian anthropologist.”

He also had political opinions, although they are hard to sort out. In his book on The Futurians, Knight has Blish as a reactionary—someone who believed in the theory of fascism even if he did not like it in practice. (This view set him at odds with almost all of the other Futurians.) But Thayer thought Blish of the late 1940s sadly besotted by democracy. At the same time, he was hunting for good leftish magazines, finding the New York Times “arch conservative.” It may be that—as he said—he just liked arguing, and so was constantly in search of a position to set himself apart from others.

The 1950s were probably Blish’s most creative period. He published his MA thesis—responding to critics of Ezra Pound—in The Sewanee Review. He also worked for society’s promoting the writings of James Branch Cabell and C. S. Lewis. He turned out a ton of fiction, including his most famous pieces, “The Okies” series about cities that fly through space, and A Case of Conscience. He joined learned to pilot a plane and joined the Civilian Air Patrol in 1955. Relocated from Greenwich Village to Milford, Pennsylvania, he worked with Pfizer as science editor and public relations counsel.

Blish continued to write and work diligently through the 1960s, when he also went to work for the Tobacco Institute, helping defend cigarette manufacturers against charges of causing cancer. He published more science fiction, and expanded into writing historical fiction. He and Kidd divorced, and Blish married Judith Ann Lawrence. He started writing novelizations of “Star Trek” in 1967 and the following year he and Judith Ann moved to England. Blish died there in 1975, of lung cancer.

Blish wrote, it seems, fueled on an inordinate amount of beer—eight or nine quarts per day. Blish claimed it had little effect on his writing, although Kidd said that his manuscripts became increasingly unreadable with the amount he imbibed, and by the end most evening he had set his writing aside to listen to music and drink. The alcohol was one frustration in their marriage; money was another; according to Kidd, Blish could also be very cruel. The science fiction writer Algis Budrys thought him profoundly unhappy. Blish, he said, felt

“that life in the 20th century was an imposition on a person of sensibility. He saw it all as a game—mind you, a deadly serious one—in which he, a person of intellect and sensibility, was the same as he would have been in any era, but the particular era into which he had (at random? intentionally?) been dropped was one in which intellect and sensibility were not prized. Therefore, it behooved him to make the best of it. If that meant peddling cigarettes and/or antibiotic salves for cows’ udders, so be it. If it meant devoting one hour each day to writing sports fiction (when no other market offered), so be it. . . . And if it meant writing science fiction in order to demonstrate one’s intellect, well, then, that, too, would be done.”

Blish tried to bring some of his intellect and sensibility to science fiction—he aspired to be more than a hack (although he acknowledged hack writers were still better than a lot of those authors getting published in science fiction magazines.) In his own criticism—initially published in fanzines under the handle William Atheling, Jr.,—the name that Ezra Pound used for his music criticism—Blish brought the tools of the New Critics to bear on science fiction. He championed stories that had tight structures, valuing them above pure invention, although he admitted that some of his own stories could be—in the vein of A. E. Van Vogt—simply busy plots. Blish had come of age reading John W. Campbell’s Astounding but he came to dislike Campbell, seeing him as having no ear, no sense of style, and-eventually—fatally compromised by his love for psychic sciences. Blish liked Theodore Sturgeon and Damon Knight and Eric Frank Russell.

His own science fiction dealt, especially, with the theme of being trapped, and the story’s structures, as Ketterer notes, often involved a protagonist escaping from one form of imprisonment only to end up in another, different prison. Over the years, his view on science fiction, and what it did, changed. In the early 1950s, while still relatively new, he continued under Campbell’s influence and saw science fiction as an extrapolation from the known. Later, after reading Thomas Kuhn’s Structure of Scientific Revolutions, he reformulated his idea, and science fiction became a way to transcend paradigms—a way to imagine whole new kinds of science. In line with his own thematics, his final view on science fiction was that it was a form of imprisonment. The science fiction writer might think himself or herself into a new paradigm—but that was only an illusion. Any attempt to form a new paradigm necessitated bringing in fantasy—religion, miracles, the transcendent—in through the back door.

This view of science fiction—and science—connected with Blish’s affection for Spengler’s view of history. As Blish saw it, the current civilization was breaking down. Humans had confronted as much reality as they could for the time being, and so were returning to the warm embrace of irrationality—flying saucers were the subject and object of a new religion, one that ultimately rejected science. It is hard not to see this pessimistic view as reflecting Blish’s own life circumstances: as he was dying, he was certain that civilization was, too. Blish was the epitome of intelligence and sensibility, and without him the world would be bereft of those traits.

There were a number of possible ways Blish may have become aware of Fort—likely in the 1930s. He was reading F. Orlin Tremaine’s Astounding Stories, and that magazine serialized Fort’s Lo! in 1938. As a high school student—somewhere between 1934 and 1938—he started corresponding with Tiffany Thayer, which is not surprising given that Blish was forward enough to get stories for his fanzine from established writers. The correspondence supposedly continued into Blish’s military service. Certainly the two shared some of the same enthusiasms, including a love of Ezra Pound. The correspondence was accidentally destroyed in 1955, though, and the only letter that remains was written in 1956, with Blish congratulating Thayer on his “Mona Lisa” (which incidentally influenced Blish’s own forays into historical literature). Thayer would likely have mentioned Fort to Blish. As well, he may have heard about Fort from other science fiction writers—Hamilton, whom he published in “The Planeteer” was a Fortean and had himself corresponded with Fort.

According to Ketterer, Blish joined the Fortean Society while he was at Rutgers, so sometime between 1938 and 1942. The source for that claim is not given, though. Blish’s friend, Lowndes, noted that he was a member of The Fortean Society in the early 1940s, and he was in a position to know. Thayer mentioned Blish in the seventh issue of The Fortean Society Magazine, June 1943, listing him with other science fiction writers who were drawn to Fort. It was around this time that Blish published an essay on Charles Fort in a science fiction magazine, but his reference to it is vague and I have yet to track it down. It may have been in Super Science Stories 1943). Thayer and Eric Frank Russell were still discussing Blish as a Fortean—with to much of a penchant for democracy, in Thayer’s estimation—in the spring of 1949. But by then Blish had also initiated correspondence with Russell on his own—and was making it clear that while he remained a member of the Fortean Society, he was no longer a Fortean.

Blish’s problem with the Fortean Society was hat it had become too much enamored of dissent for dissent’s sake. Science and scientists could sometimes be hubristic, but there was also good work going on, and Thayer, especially, refused to see it, opting instead to champion every whackjob—making Fort’s name synonymous with cranks, exactly what the Fortean Society was supposed to militate against. Blish still loved Fort as a writer—and appreciated Thayer’s style, which was why he read Doubt—but thought that both had become intellectually lazy. This perspective was in line with John W. Campbell’s critique of Fort, as expressed to Russell—although Campbell made his pronouncements a few years later. Exactly how the lines of influence work—or if the ideas were developed in parallel—is unknown.

Blish approached Russell to join the Vanguard Amateur Press Association, offering to trade membership dues for issues of The New Statesmen (in Blish’s opinion, the only good magazine on the left). He was also drawn to Russell as a Fortean. It seems that Blish’s “Tumbrils” may have been dealing with Fort at the time; and another publication mailed out under the VAPA’s aegis, Norman L. Knight’s “Knight’s Mare” was also dealign with Fort—and Fortean topics more generally. In 1948, Knight took on the renegade economic Henry George, about whom Thayer had written. (The idea of social credit and monetary reform was important to Forteans, as well as to Ezra Pound. There is supposed to have been an article on the topic in The Sunday Times around this time as well, discussing disagreements among English Forteans over the issue, but I have not yet found it, either.) He was also curious to know if Eric Frank Russell was writing under the name Hal Clement. (He wasn’t.)

Thayer, too, had opened to door on the nature of Forteanism in asking members to write an essay on the topic for The Humanist magazine. He eventually decided to send in his own piece, but the competition intrigued Blish and got him thinking about the matter. On 8 April 1949 he wrote Russell,

“You’ll find something in the forthcoming bundle that should elicit some rather special interest in your Fortean soul, I think. … Are you planning to enter the competition announced in the current DOUBT? I think I am, although I am perhaps entirely too critical an admirer of Fort to be the proper person to write such an essay from Thayer’s point of view. However, we’ll see. I want to look over a copy of THE HUMANIST before I make up my mind, and I suppose that if I do enter I should pay my dues, too. I don’t much want to do it, yet I would like to go on getting DOUBT; its breeziness tickles me even when it is setting my teeth on edge with a fruitcake of stale nutcults. Dilemma, dilemma. … Just for the hell of it, I answered the questions you proposed as an examination for the degree of Professor of Suspicion. The results were interesting and I may publish them later. However, one of the things that deters me is a persistent doubt as to your attitude. I can often explain—and I say this with all due humility—current scientific thinking on the questions which become Fortean targets: the business about what the ‘absolute’ speed of light ‘relates’ to, for instance. Yet I am nagged by the feeling that most Forteans, for all their admiration for their master’s flexibility of mind, would not readily admit that any ‘orthodox’ scientific reasoning could be reasonable; that they would rather raise such questions than listen to the proposed answers; and would automatically reject any such answer which did not make the answerer out to be a nincompoop. The reason I say this is that I have noted that many of the theories Thayer entertains, and many of the things that seem to puzzle him (I judge what puzzles him by what he mocks intensively) could be settled by a very brief search of the pertinent literature, or by application to some easily-accessible authority in the field. One needn’t feel that the statements of authority are final, but certainly one can accept any answer that seems to be reasonable, even if authority makes it. No? And this process,w which would rid the Society of a lot of its most profitless baggage—astrologers, flat-earth enthusiasts, pyramidologists, and other psychopaths—would still leave plenty of room for Fortean activity; I think, for instance, that it is right and proper for the Society to champion Drayson until the matter can be settled, or until the apparently stupid stubbornness of astronomers can be overcome enough to make them really attack the problem; and real investigations of the major phenomena which Fort discovered—wild talents, apparent teleportatory phenomena, etc. This material yells for study, and only the Fortean society [sic] could study it adequately—providing that the Society were willing to give over harboring ideas and idealizers only because they are nutty, and were willing to apply the scientific method, which you will observe Fort loved and championed all his life against scientists who abused it. The balloon-pricking could still be operated under full steam, too, for each century has its Haeckels. Some selectivity as to target should be exercised, though, or the Society becomes just sort of a clearing house for people who think they are being controlled by radio by little green (Negro-Jewish-Russian) men. That’s what it is now, for the most part. … I burden you with this because I have never been able to get Thayer to listen; would you tell me what you think?

“P.S. Most symptomatic, I think, is Thayer’s obvious belief that there is no such thing as an atomic bomb. Do you find this a sane attitude—especially for a Fortean, who shd/be flexible enough to accept the incredible ahead of ordinary scientists?”

In an undated update, Blish went into further detail, reserving for himself the right to criticize science as he saw fit, but also to defend it—and attack Forteanism: he wanted to be both a Fortean and against Forteans, his intelligence making him a unique specimen:

“Well, about Forteanism; I welcome the opportunity to talk with a reasonable example of the breed. I too object and powerfully to the more publicity-conscious scientist and his habit of erecting conjectures into ‘facts.’ I object also to the much more common kind of scientist: the man who allows the pressure of our degree-mills to rush him into publishing incomplete studies just for the sake of having been published—this is not publicity-consciousness exactly, since papers in scholarly journals seldom reach more than a few thousand people; it is instead a reflection of our university set-up, which requires a scientist to publish, publish, publish, for the prestige of the university. (The same is true of our English departments, and unhappily it’s much easier to say nothing in a critical article than it is in a scientific paper.) But the Forteans would have you understand that both these types of scientists are in a large majority, and this is simply not so. How do I know? Well, I am a technical editor for three trader newspapers dealing with foods and drugs. Once every two weeks I go up to the New York Academy of Medicine library and read every single new scientific paper that has come in which impinges in any way upon those two fields. As a science-fiction writer and a person with a good deal of intellectual curiosity, I also read technical papers in physics, astronomy, etc., etc. Every so often I come across a paper that seems to me to have been rushed into print without adequate reason; sometimes I find claims that the tests quoted do not bear out; almost always, except in Lancet, I find appallingly bad English (though this is not very germane to the present point.) But for the most part, and by that I mean 90% of the time, the papers I see preserve a cautious, honest, indeed Fortean approach tot he material—in the best sense of that word Fortean, for there is I think a very bad sense of it. Of course much of the work that I see uses a lot of accepted previous material as a springboard—but if you check those references, you generally find them pretty carefully and skeptically done, too. When they weren’t, there follows a rash of attacks upon the author from other scientists. (Witness Lancet’s recent editorial attack upon Brewster’s anti-histamine cold therapy, or Dingle’s terrific blast at the new Milne relativity; or the way in which Ehrenhaft’s rather sloppy—and very publicity-conscious—ideas have been attacked.) It is difficult to say that these men are attacking their confreres because orthodoxy has been violated, for the attacks are mostly procedural rather than ideological—tending to point up inconsistencies, in the methods used, unwarranted assumptions in the conclusions, etc. In Milne’s case the battle has been joined with especial vehemence because Milne’s way of approaching relativity is highly epistemological, stepping rather outside the limits of strict empirical observation into realms where philosophers more usually dwell, and has brought back into the sciences that terrifying question, HOW DO WE KNOW WHAT WE KNOW? Milne’s is, I think, a most Fortean cast of mind, but it is interesting to see that he has found many defenders with the supposedly solid ranks of ‘orthodox,’ so that it now appears that his two time-scales and his standards of communicability may become the basis for a violently revolutionary reorientation of our ways of thinking about time and the stars. This revolution is happening much too rapidly to give substance to the FS’ assumption that all scientists (plus or minus its own pets) are involved in some great conspiracy to establish a priesthood. Indeed, I would guess that the fixed unwillingness of most Forteans to accept anything except dog-eared superstitions, popular myths, irruptions of psychopathy, old buttons, safety pins, bits of string, and small rabbit-pellets of thought, reflects an attitude as dogmatic as is findable anywhere in the world today. When you have to say ‘no’ just because you’ve discovered that somebody else might agree with you, you’re in a very bad way; your thought processes have become frozen; you’ve erected doubt, as Thayer has, into a religion stricter than Catholicism or Communism. When you have to add to this the one very bad things about Charles Fort—the fact that he was inherently lazy, and was too delighted with his own iconoclasm to investigate the sciences he attacked in order to determine whether or not his attacks really held water—and the fact that his laziness, too, has become a fixed pattern of behaviour [sic] within the Fortean Society, you have a bad mental situation all around. Fort himself delights me and always has, because he was such a consummate artist; he has, you will not, plenty of appeal for other artists—he is even mentioned in Ezra Pound’s most recent Cantos—but the inattention with which he was greeted by scientists was deserved, for his laziness is immediately evident to the unpoetic mind. As for the Society, its laziness of thought is positively stupendous; for it is laziness, and nothing else, to accept everything strange only because it is strange.”

With this missive, Russell presumably had had enough of the topic, as Blish next wrote,

“I am agreeable enough toward not arguing with you about F.S. policies. It occurred to me that you might want to argue; if not, so be it. Let me say only that your defense, incomplete as it is, reminds me very much of a defense of the F.S. I once made, and got printed in a science-fiction magazine, in the days when I thought the F.S. did represent a tonic organization for the perpetuation of skepticism. I don’t think so any longer, as you may have observed; I have found since, very reluctantly, that it does little but celebrate the virtues of institutionalize wrongheadedness, which is a very different thing. Your opinion, sir, and mine; sacrosanct both. (As for me, I’m not Fortean, though I love laughter.)

“I hardly expected you to greet the last Vanguard mailing with cries of joy, mostly because of all the musical discussion. But I was rather hoping that you might have comments on Knight’s ‘Fortean Footnotes’ (in Knight’s Mare), since it deals with a universe of discourse with which you’re familiar. Eh?”

At the time, Fort was often lumped with other alternative thinkers by science fiction writers, including Korzybski (“General Semantics”) and soon-to-be L. Ron Hubbard, with his Dianetics. Blish was strongly influenced by the writer A. E. Van Vogt, who himself was a student of Korzybski. And after the publication of Dianetics, both Blish and Van Vogt became adherents of the new methods—although with Blish Dianetics was only a passing phase, while with Van Vogt it became central to his thought. (John W. Campbell was also impressed by Dianetics.) These three subjects—General Semantics, Dianetics, and Forteanism—continued to be related in Blish’s thinking.

For although he had lost enthusiasm for the Fortean Society, he continued to run into Fortean writing, and even incorporate its themes into his won writing. He educated his first book of criticism to the Fortean Claire P. Beck. He followed Russell’s career, and praised him in his critical writing—as well as acknowledging that Russell’s breezy style owed a debt to Thayer’s own. His 1950 tale “There Shall Be No Darkness,” for example, is about werewolves, and offers a scientific explanation of lycanthropy as a ‘wild talent,’ a la Fort’s book of that name. Indeed, “Wild Talents” was one of Fort’s great gifts to science fiction.

As an example, one only needs to look at Blish’s first novel published in book form, Jack of Eagles, published in 1952, which not only incorporates wild talents, but also includes the Fortean Society. Danny Caiden—like Blish himself, a writer for food trade magazines—finds himself having odd experiences—being able to find what is lost, hearing voices, foreseeing the future. His wild talent even costs him his job, and so he turns to three different resources: the university parapsychology department, the psychic research society, and the Fortean Society, whose leader is clearly modeled on Thayer:

“The Forteans were even less helpful, though friendly. The local branch of the Fortean Society had only a post office box address. When he finally found them, it was by way of Who’s Who. Their local leader turned out to be Cartier Taylor, a popular author, a man who had written so many colorful and occasionally acute thrillers that even Danny had heard of him. Indeed, the Fortean group seed to be crawling with writers of various calibres, most of whom were more impressed by their Master’s brilliant writing style than with his disordered metaphysical theories.

Taylor,a slickly handsome man past middle age in the process fo going to seed, but with a gift fot brilliantly bitter chatter which dazzled Danny into complete inarticulateness, was more than willing to load Danny up with half a hundred reports of wild talents of every conceivable kind. He had bins of them, collected by assiduous Forteans all over the world, and filed under such titles as ‘Pyrotics,’ ‘Poltergeists,’ ‘Rains of Frogs,’ and ‘Oil-Prones.’ But nothing that he had to offer in the way of theories to account for such reports seemed better than idiotic. Indeed, he seems dot have a special bias toward the idiotic, and to be out to trap Danny into every possible concession that ‘orthodox’ theories of the state of the universe were nonsense.

He viewed scientists-in-the-mass as a kind of priesthood, and scientific method as a new form of mumbo-jumbo. This twist made him partial to astrology, hollowearth notions, Lemuria, pryamidology, phrenology, Vedanta, black magic, Koresanity, Theosophy, Rosicrucianism, crystalline atoms, lunar farming, Atlantis, and a long list of similar asininities—the more asinine the better. At bottom, however, every one of these beliefs (if Taylor believed any of them; Danny could nto tell whether he subscribed to any given doctrine because he liked it or only because he liked to be in revolt against anything more generally accepted) turned out to rest upon some form of personal-devil theory: Roosevelt had sold the world down the river, the world press was out to suppress reports of unorthodox happenings, astronomers conspired//50//to wangle money for useless instruments, physicists were secretly planning to promote the purchase of cyclotrons by high schools, the Catholic Church was about to shut down independent thinking throughout the United States, doctors were promoting useless or dangerous drugs because they were expensive—all with the glossiest of plausible surfaces, all as mad as the maddest asylum-shuttered obsession of direct persecution. Danny was not at all surprised that Taylor was determinedly and brilliantly trying to sell him Dianetics as Danny backed out of the door of the writer’s apartment.

Yet Fort himself assuredly made exciting reading, as Danny found directly afterward at the public library. He could see why writers loved the man, He wrote in a continuous and highly poetic display of verbal fireworks, superbly controlled, intricately balanced, witty and evocative at once. His attitude toward his world seemed to be a sort of cosmic flatulence, about midway between the irony of Heine epigrams which Danny remembered well and Ritz Brothers slapstick which he would be happy to forget.

But like Taylor, his explanation for the things he had observed, collected at second hand, or simply collated were deliberately outrageous. Every now and then Danny found in one or another of Fort’s four books a glimmering trail toward something useful—and every time Fort took the developing insight and stood it on its head, or worse, distorted it into complete childishness.

A scientist with a sense of humor and more than usual patience with sloppy thinking might have made something of Fort’s Wild Talents, the one book of the four which bore centrally upon Danny’s troubles. But for Danny, who had no scientific training and a desperate need to know now what it was all about, there was nothing to be found but the assurance that a lot of other people had been in his fix, or something rather like it.”

Through a series of adventures, Caiden eventually learns that a cadre of people with wild talents, including Taylor and a work friend, are battling the Psychic Research Society on a number of fronts, including the manipulation of markets. The Fortean side, in this case, though, has the advantage because they have gone some ways towards understanding, scientifically, the talents while the psychic researchers are befuddled by spiritualist claims. The paraspychologist is also on the verge of scientifically understanding the wild talents, and he sets Caiden to a place where—although he is an amateur but, again like Blish is conversant with a wide array of sciences and has excellent recall—can finally make the final breakthrough in having a scientific explanation for these extra sensory perceptions. The key, as it turns out, is Korzybski’s interpretation of General Relativity, which allows Caiden to understand that there are multiple universes, and ESP allows one to tune into the frequencies of these other universes and understand which outcomes are most likely.

The story, then, puts a Blish doppelgänger in the position to merge real science with Forteanism to explain what Campbell was, at the time, calling pay powers. It wouldn’t be long, though, before Blish was dismissing Campbell exactly because of his interest in ESP and attempts to make a scientific understanding of the subject. Campbell had once thought that Fort’s books contained the seeds of at least four new sciences. Blis agreed—and then he was on to other matters, thinking that enthusiasm sophomoric, and not up to his own intellectual rigor.