(Corrected after first posting.)

Esteemed as a Fortean—but seemingly not very interested in Fort, Fortean ideas, or the Fortean Society, except to the extent they could serve his own purposes.

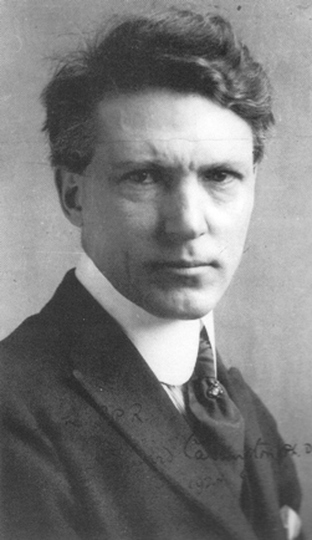

Hereward Carrington is almost famous enough not to deserve an entry here: a ghost hunter and investigator of psychic phenomena, he was one of the leaders in the field during the first half of the twentieth century as spiritualism transformed itself into parapsychology and made some progress in institutionalizing itself as a form of knowledge—a species of science—and not (just) esoteric Christianity in both the United States and England. (The story in France is slightly different. I don’t really know what was going on in Germany along these lines, or other European countries for that matter.) But, famous as he is, it is worthwhile to at least do a quick overview of his life and work to get a sense of the communities that abutted and overlapped the Forteans.

Hereward Carrington was born to Robert and (Sarah) Jane (Pewtress) Carrington on 17 October 1880 in Jersey, on the Channel Islands. Robert had been born on the Isle of Man, and worked int he civil service: he was away from home at the time of the 1881 census, leaving Jane as head. Hereford had three brothers, Herbert, Hedley, and Fitzroy, and one sister, Irma, all older than him. Healey made his way to the United States, and Hereford followed him; according to the census, he immigrated in 1889. Other sources have him making the trip in 1888, which seems on the young side, but seems the more correct date. The brothers were living—with Hedley’s wife—in Minnesota, where Hedley was a manager for a rubber company and Hereford a clerk at a bookstore. (Reports are he returned to England around age 12 for education.)

Esteemed as a Fortean—but seemingly not very interested in Fort, Fortean ideas, or the Fortean Society, except to the extent they could serve his own purposes.

Hereward Carrington is almost famous enough not to deserve an entry here: a ghost hunter and investigator of psychic phenomena, he was one of the leaders in the field during the first half of the twentieth century as spiritualism transformed itself into parapsychology and made some progress in institutionalizing itself as a form of knowledge—a species of science—and not (just) esoteric Christianity in both the United States and England. (The story in France is slightly different. I don’t really know what was going on in Germany along these lines, or other European countries for that matter.) But, famous as he is, it is worthwhile to at least do a quick overview of his life and work to get a sense of the communities that abutted and overlapped the Forteans.

Hereward Carrington was born to Robert and (Sarah) Jane (Pewtress) Carrington on 17 October 1880 in Jersey, on the Channel Islands. Robert had been born on the Isle of Man, and worked int he civil service: he was away from home at the time of the 1881 census, leaving Jane as head. Hereford had three brothers, Herbert, Hedley, and Fitzroy, and one sister, Irma, all older than him. Healey made his way to the United States, and Hereford followed him; according to the census, he immigrated in 1889. Other sources have him making the trip in 1888, which seems on the young side, but seems the more correct date. The brothers were living—with Hedley’s wife—in Minnesota, where Hedley was a manager for a rubber company and Hereford a clerk at a bookstore. (Reports are he returned to England around age 12 for education.)

By 1905, Hereford had relocated to Manhattan, and by 1910 was married to a woman named Helen Wildman. She was about a decade older. (As a point of interest, the 1910 census gave his immigration year as 1895.) Helen was also born in England, and had emigrated in 1902 or 1903. Apparently, they had married around 1907—just as Fort was beginning to collect reports of anomalies—and Carrington was working as a short story writer. Helen did not have a job. Apparently Carrington was selling enough to make a living, but, after a desultory search, I have no been able to find any short stories by him from before 1910. Wikipedia has it that he worked as an editor for the pulp magazine publisher Street and Smith, but does not give a citation. However, a bio in the Haldeman Julius Little Blue Books does mention that he was for a time editor of Street and Smith’s 10-cent novels.

Carrington also had other interests, which can be documented. He was a magician and was giving performances as early as 1901 in Minnesota--some reports date his performances back to his early teens, with shows through the 1890s. He was also interested in spiritualistic phenomena and the question of the soul’s materiality and immortality, writing for “The Open Court” on the matter in 1905. (A journal of science and religion, the “Open Court” ran articles by others who would become Forteans as well, into the 1920s.) Around the time of his marriage, he became involved with ProfessorJames H. Hyslop, of the Society for Psychical Research in New York. The two proposed the weighing of murderers just before and after their execution to determine the weight of the soul. By that time, Carrington was presenting himself as a Doctor. The idea was spurred by the work of Dr. Duncan Macdougal, of Haverhill, who went around trying to weigh the sick just before and after they died. That work had prompted skeptical comment from a number of people, including Nikola Tesla and the future Fortean Anton J. Carlson, professor of physiology at the University of Chicago. That year, it was also announced he would publish “The Physical Phenomena of Spiritualism: Fraudulent and Genuine.” With Hyslop, he was known as skeptical and clever—trained in magic himself—and a unmasker of frauds. In this sense, he was something like Houdini, another magician intrigued by spiritualism enough to investigate, but a dedicated skeptic and exposer of hoaxes. It was through these investigations that Hereford met his future-wife, Helen.

In 1908, Carrington became involved in what is probably his most famous case, the study of the Italian medium Eusapio Palladino. He traveled to Naples as part of a committee from the Society for Psychical Research and was initially impressed, even as they caught her hoaxing some of the spiritual phenomena. Carrington chaperoned Palladino to America and had her perform and be studied by psychologists. He wrote a positive review of her skills for McClure’s but eventually became disillusioned, concluding that almost everything Palladino did was trickery—almost: perhaps there were still a few mysterious powers she had that no one could explain.

Carrington was tipping his hand; just as Houdini was intrigued in spiritualism but thought it all hogwash, Carrington was intrigued, but thought that there was something there, something real, something worth study. He published The Coming Science in 1908, arguing that spiritualism could be explained scientifically, that there were new laws and new forces to be worked out by those open-minded enough to study the phenomena, And he would spend the next decades investigating the subject, writing about it, probing it. He would associated himself with “Scientific American” when that magazine was involved in experimenting on medical claims and spiritualistic ones. He would travel the world collecting stories and visiting mediums.

In addition to his interest in magic and spiritualism—both common enough among later Forteans—Carrington also had another enthusiasm shared by Forteans: alternative medical cures. Carrington thought that fasting was the key to good health and longevity. He published his first book on the subject in 1908—his third book overall. It raised at least a few eyebrows. “Vitality, Fasting, and Nutrition” claimed that a person could live on twelve ounces of food per day; that the cure for any disease was prolonged fasting—thirty, forty, fifty days. He rested these claims on an alternative theory of physiology, in which food is not what produces the energy needed by the body. These ideas, too, would motivate Carrington throughout his life.

Carrington remained in the United States through the 1910s, including World War I—at 38 and with no particularly military skills, he was too old to serve—but returned to England after the War, in July 1922. (He had last visited England around 1909.) Warrington may also have been traveling prior to this, as I cannot find him in the 1920 U.S. Census. He returned to the United States in October 1922, and, in later years, he would mark this as his official coming to America. In 1921, he established the American Psychical Institute, but it was disbanded after two years.

Hereward kept himself busy through the 1920s, his name often in the newspapers, writing a number of books on the topics of fasting, psychic phenomena, immortality, and magic. He ran in circles that overlapped with other future Forteans—Gertrude Hills, for example, who was also a friend of Houdini’s, and Fred Keating, another magician-cum-spiritualist investigator. I am not sure what happened to Helen. But in the 1930s, Hereward was re-establishing his American Psychical Institute, during the course of which he met Marie Phelps Sweet. (They were studying the Boston medium Margery, earlier investigated by Houdini and Keating.) They married 21 July 1932 and investigated psychic phenomena together, for example transcribing a session by Edgar Cayce, the famous psychic. Along with future Forteans Harry Price and Nandor Fodor, he investigated “Gef the Talking Mongoose,” on the Isle of Man. In 1934, Hereward examined the psychic (and future Fortean) Eileen Garrett, describing her sessions as the best proof of life-after-death yet adduced. This was at odds with Garrett’s own understanding of her gifts. Carrington became a U.S. citizen in 1934, too.

In 1935, he published “Loaves and Fishes,” on miracles, his 24th book (I believe). He supposedly published books int he 1940s, too, but I have not seen anything from the period; nothing until the 1950s. That is not to say that Carrington was slowing down during this period: he continued his investigations and his name continued to appear in newspapers. The 1940 census has him living in New York with Marie and Marie’s son from a previous marriage, DeWilton. At some point, he and Marie moved to southern California—likely this was around 1951, perhaps as early as 1944 according to Steve Rivkin, who is working up a biography on Carrington—where they continued to fast for long periods of time, weeks even. (In 1934, he was 5’10” and 135 pounds.) He wrote for Eileen Garrett’s periodicals, and even published a book through her press on Palladio, this in 1954. Carrington died in Los Angeles in 1958, only a year before the Fortean Society would see its own demise. He was 78.

[Rivkin has it that Carrington's second wife, Marie, did not go with him to LA, but left him for another man, only coming to LA later, but not as a lover; they did co-author the book together. But Carrington married a third woman who changed her name to Marie for reasons I do not know.]

Throughout his long life and frequent investigations, Carrington often dismissed mediums as tricksters, sometimes after falling for their tricks first. He didn’t give up his belief in the immortality of the soul though. Marina Warner, who is otherwise quite perceptive, dismisses him as a proponent of Theosophy. Without—admittedly—having made a study of his writings, I can’t quite see the connection. His interests were more conventionally spiritualistic and psychic.

There are many paths by which Carrington could have come to Fort and the Fortean Society. An omnivorous reader and scholar of psychic phenomena, he likely read Fort when he originally published his first four books, or shortly thereafter. Carrington doesn't seem to have left any comments on Fort, but he did use him as a source for poltergeist stories in a book co-written with Nandor Fodor: “Wild Talents” was thus the Fortean book to most leave an impression. Carrington did write for science fiction magazines, too, and so probably came across the name there, as well. As for his coming to the Society? It seems likely that Fred Keating, who became a close friend of Tiffany Thayer, introduced Carrington to Thayer.

We do know that Thayer met Carrington in person. In a 1959 letter to Eric Frank Russell, he remembered spending a night with Carrington. They “chased spirits all night.” Exactly when this occurred is impossible to know from the description Thayer gave, but sometime in the late 1930s or 1940s seems plausible. Thayer remembers it as occurring “probably in 1940,” but then he dates it by saying that Edgar Cayce and Eileen J. Garrett had not yet been discovered, Rhine was not yet at Duke, and Fodor was studying the mongoose of Gashen’s Gap—which doesn’t make a whit of sense, since Cayce had come to public attention by 1925, Carrington studied Garrett in 1934, Rhine joined Duke in 1927, and Fodor looked into the Talking Mongoose in the mid-1930s. At any rate, the group included, in addition to Carrington, Eric J. Dingwall., Fred Keating, Francis I. Regardie, who may have been an associate of Aleister Crowley and, oddly, Scott Nearing. “The chief topic that evening was the dearth of good claimants to mediumistic faculties worth investigating. Both Carrington and Dr. Dingwall were prepared to go anywhere in the world to study such a case, but not one of us could supply a name which presented a serious challenge to two so expert as these.”

Carrington rated only six mentions in the Fortean Society magazine “Doubt,” many of them trivial. But the very first one showed he was held in esteem. In Doubt 15, Summer 1946, Carrington was elevated to the station of “Honorary Founders.” The circumstances around this award are a bit confusing. Most Honorary Founders were supposed to fill the role of the original founders after they died. (The exact number of original founders itself was a matter of some debate, but Thayer opted for 11.) Carrington, though, took the place of J. David Stern, who would outlive both Thayer and Carrington as well as the Society, not dying until 1971. He had quit the Society in a huff in the early 1940s, though, after Thayer wrote what Stern though were seditious columns in the magazine. Why Thayer waited five years to replace Stern is not clear—perhaps he thought he could entice him back—but it came in the years just after World War II, when Thayer was in a mood to organize the Society.

Two of the other mentions were prompted by books Carrington wrote: in Doubt 42 (October 1953), Thayer mentioned that Carrington had co-authored a book with Sylvia Muldoon on Astral Projection. And in Doubt 48 (April 1955) Thayer gave relatively effusive praise to Carrington's new book on Palladino: “MFS Eileen Garrett, publisher of Tomorrow, has published a new work by Honorary Founder Hereward Carrington. This is the American Seances with Eusapia Palladino. As older members will recall, Palladino put on the best and most convincing mediumistic show that the world has ever seen. Although Hereward was in on the tests, and wrote a big book about her in 1909, he still does not know how she accomplished some of her effects. These seances took place in 1909 and 1910, after the other book was written. For believers and non-believers in ‘spiritualism,’ this exciting data. From the Society $3.75.”

Carrington was also mentioned upon the death of Harry Price, a member and British ghost hunter. Thayer said that he was soliciting remembrances of Price from Carrington and Fodor. Whether he did or not—whether they responded or not—Doubt never published any such memorial to Price.

Besides the elevation to Honorary Founder, Carrington was esteemed once more by the Society—but as with every mention, it is unclear that Carrington had anything to do with Thayer’s Fortean club. (Presumably, he accepted the invitation to be an Honorary Founder, since Thayer did not add other people to the same station who did not respond or responded negatively, which shows that, at the very least, Carrington had a soft spot for Fort. Or Thayer.) In Doubt 32 (March 1951), Thayer wrote a bit titled “Hail, Carrington!”:

“Because Hereward Carrington, HFFS, was quoted in an interview as saying, ‘I am terribly disappointed by the ghosts around Los Angeles. They aren’t worth a tinker’s damn…”--the dean of psychic investigators was attacked in a two-age article by Ralph C. Pressing, editor of the Psychic Observer, issue of Nov. 25.

“Pressing and his wife are the bell-wethers of the table-tipping, tin-trumpet clan, publishers of the Psychic Observer and merchants in trumpets, luminous paint, Ouija boards, ‘Indian’ incense and ‘crystal’ balls. Not all Carrington’s published work in the past fifty years will stand up under searching Fortean criticism, but this attack by Pressing would make up for a good many lapses into faith. Let Forteans be known by the enemies they make.”

After Carrington died, Thayer wrote to his confidante Eric Frank Russell that he thought the natural successor would be Eric J. Dingwall. Thayer tendered the offer and Dingwall accepted, in April 1959, four months before Thayer himself would die. That same month’s issue of Doubt (#60), included an obituary for Carrington. “Sadly and solemnly,” Thayer wrote, “You must be informed that Hereward Carrington left us for his ultimate investigation of psychic phenomena last December 26.” Thayer was glad that he was never fully convinced of psychic phenomena, dismissing 98% of the claimants as frauds, but wanting to explore and explain the residual 2%: “That is why the Fortean Society has been proud of Hereward Carrington’s service as an Honorary Founder of the Society since 13 FS, 1943 old style.” (Thayer got that wrong: In 1943, Carrington was listed as an Accepted Fellow, eligible to become an Honorary Founder, but at that time the Fortean Society paperwork continued to list J. David Stern as a living Founder.) He then went on to praise Carrington’s successor:

“Since [about 1940], Dr. Dingwall has not only constantly added to his kudos by his own consistently Fortean approach to psychic science in Britain, but--at the death of Harry Price--still more dignities, honors and responsibilities gravitated upon his shoulders. In the next issue of DOUBT we shall have more details of the titles and labors of Dr. Eric J. Dingwall. At this time it is possible to say only that Dr. Dingwall has agreed to accept the post of Honorary Founder of the Fortean Society, vacated by our loss of Hereward.

“So if any of you get, ‘from the other side,’ the secret word that Hereward shared with Houdini, you will have to prove it to a very Solomon of a judge in Eric J. Dingwall.”

Carrington deserves a fuller treatment, perhaps a group biography of him, Price, Fodor, and Dingwall.

Carrington also had other interests, which can be documented. He was a magician and was giving performances as early as 1901 in Minnesota--some reports date his performances back to his early teens, with shows through the 1890s. He was also interested in spiritualistic phenomena and the question of the soul’s materiality and immortality, writing for “The Open Court” on the matter in 1905. (A journal of science and religion, the “Open Court” ran articles by others who would become Forteans as well, into the 1920s.) Around the time of his marriage, he became involved with ProfessorJames H. Hyslop, of the Society for Psychical Research in New York. The two proposed the weighing of murderers just before and after their execution to determine the weight of the soul. By that time, Carrington was presenting himself as a Doctor. The idea was spurred by the work of Dr. Duncan Macdougal, of Haverhill, who went around trying to weigh the sick just before and after they died. That work had prompted skeptical comment from a number of people, including Nikola Tesla and the future Fortean Anton J. Carlson, professor of physiology at the University of Chicago. That year, it was also announced he would publish “The Physical Phenomena of Spiritualism: Fraudulent and Genuine.” With Hyslop, he was known as skeptical and clever—trained in magic himself—and a unmasker of frauds. In this sense, he was something like Houdini, another magician intrigued by spiritualism enough to investigate, but a dedicated skeptic and exposer of hoaxes. It was through these investigations that Hereford met his future-wife, Helen.

In 1908, Carrington became involved in what is probably his most famous case, the study of the Italian medium Eusapio Palladino. He traveled to Naples as part of a committee from the Society for Psychical Research and was initially impressed, even as they caught her hoaxing some of the spiritual phenomena. Carrington chaperoned Palladino to America and had her perform and be studied by psychologists. He wrote a positive review of her skills for McClure’s but eventually became disillusioned, concluding that almost everything Palladino did was trickery—almost: perhaps there were still a few mysterious powers she had that no one could explain.

Carrington was tipping his hand; just as Houdini was intrigued in spiritualism but thought it all hogwash, Carrington was intrigued, but thought that there was something there, something real, something worth study. He published The Coming Science in 1908, arguing that spiritualism could be explained scientifically, that there were new laws and new forces to be worked out by those open-minded enough to study the phenomena, And he would spend the next decades investigating the subject, writing about it, probing it. He would associated himself with “Scientific American” when that magazine was involved in experimenting on medical claims and spiritualistic ones. He would travel the world collecting stories and visiting mediums.

In addition to his interest in magic and spiritualism—both common enough among later Forteans—Carrington also had another enthusiasm shared by Forteans: alternative medical cures. Carrington thought that fasting was the key to good health and longevity. He published his first book on the subject in 1908—his third book overall. It raised at least a few eyebrows. “Vitality, Fasting, and Nutrition” claimed that a person could live on twelve ounces of food per day; that the cure for any disease was prolonged fasting—thirty, forty, fifty days. He rested these claims on an alternative theory of physiology, in which food is not what produces the energy needed by the body. These ideas, too, would motivate Carrington throughout his life.

Carrington remained in the United States through the 1910s, including World War I—at 38 and with no particularly military skills, he was too old to serve—but returned to England after the War, in July 1922. (He had last visited England around 1909.) Warrington may also have been traveling prior to this, as I cannot find him in the 1920 U.S. Census. He returned to the United States in October 1922, and, in later years, he would mark this as his official coming to America. In 1921, he established the American Psychical Institute, but it was disbanded after two years.

Hereward kept himself busy through the 1920s, his name often in the newspapers, writing a number of books on the topics of fasting, psychic phenomena, immortality, and magic. He ran in circles that overlapped with other future Forteans—Gertrude Hills, for example, who was also a friend of Houdini’s, and Fred Keating, another magician-cum-spiritualist investigator. I am not sure what happened to Helen. But in the 1930s, Hereward was re-establishing his American Psychical Institute, during the course of which he met Marie Phelps Sweet. (They were studying the Boston medium Margery, earlier investigated by Houdini and Keating.) They married 21 July 1932 and investigated psychic phenomena together, for example transcribing a session by Edgar Cayce, the famous psychic. Along with future Forteans Harry Price and Nandor Fodor, he investigated “Gef the Talking Mongoose,” on the Isle of Man. In 1934, Hereward examined the psychic (and future Fortean) Eileen Garrett, describing her sessions as the best proof of life-after-death yet adduced. This was at odds with Garrett’s own understanding of her gifts. Carrington became a U.S. citizen in 1934, too.

In 1935, he published “Loaves and Fishes,” on miracles, his 24th book (I believe). He supposedly published books int he 1940s, too, but I have not seen anything from the period; nothing until the 1950s. That is not to say that Carrington was slowing down during this period: he continued his investigations and his name continued to appear in newspapers. The 1940 census has him living in New York with Marie and Marie’s son from a previous marriage, DeWilton. At some point, he and Marie moved to southern California—likely this was around 1951, perhaps as early as 1944 according to Steve Rivkin, who is working up a biography on Carrington—where they continued to fast for long periods of time, weeks even. (In 1934, he was 5’10” and 135 pounds.) He wrote for Eileen Garrett’s periodicals, and even published a book through her press on Palladio, this in 1954. Carrington died in Los Angeles in 1958, only a year before the Fortean Society would see its own demise. He was 78.

[Rivkin has it that Carrington's second wife, Marie, did not go with him to LA, but left him for another man, only coming to LA later, but not as a lover; they did co-author the book together. But Carrington married a third woman who changed her name to Marie for reasons I do not know.]

Throughout his long life and frequent investigations, Carrington often dismissed mediums as tricksters, sometimes after falling for their tricks first. He didn’t give up his belief in the immortality of the soul though. Marina Warner, who is otherwise quite perceptive, dismisses him as a proponent of Theosophy. Without—admittedly—having made a study of his writings, I can’t quite see the connection. His interests were more conventionally spiritualistic and psychic.

There are many paths by which Carrington could have come to Fort and the Fortean Society. An omnivorous reader and scholar of psychic phenomena, he likely read Fort when he originally published his first four books, or shortly thereafter. Carrington doesn't seem to have left any comments on Fort, but he did use him as a source for poltergeist stories in a book co-written with Nandor Fodor: “Wild Talents” was thus the Fortean book to most leave an impression. Carrington did write for science fiction magazines, too, and so probably came across the name there, as well. As for his coming to the Society? It seems likely that Fred Keating, who became a close friend of Tiffany Thayer, introduced Carrington to Thayer.

We do know that Thayer met Carrington in person. In a 1959 letter to Eric Frank Russell, he remembered spending a night with Carrington. They “chased spirits all night.” Exactly when this occurred is impossible to know from the description Thayer gave, but sometime in the late 1930s or 1940s seems plausible. Thayer remembers it as occurring “probably in 1940,” but then he dates it by saying that Edgar Cayce and Eileen J. Garrett had not yet been discovered, Rhine was not yet at Duke, and Fodor was studying the mongoose of Gashen’s Gap—which doesn’t make a whit of sense, since Cayce had come to public attention by 1925, Carrington studied Garrett in 1934, Rhine joined Duke in 1927, and Fodor looked into the Talking Mongoose in the mid-1930s. At any rate, the group included, in addition to Carrington, Eric J. Dingwall., Fred Keating, Francis I. Regardie, who may have been an associate of Aleister Crowley and, oddly, Scott Nearing. “The chief topic that evening was the dearth of good claimants to mediumistic faculties worth investigating. Both Carrington and Dr. Dingwall were prepared to go anywhere in the world to study such a case, but not one of us could supply a name which presented a serious challenge to two so expert as these.”

Carrington rated only six mentions in the Fortean Society magazine “Doubt,” many of them trivial. But the very first one showed he was held in esteem. In Doubt 15, Summer 1946, Carrington was elevated to the station of “Honorary Founders.” The circumstances around this award are a bit confusing. Most Honorary Founders were supposed to fill the role of the original founders after they died. (The exact number of original founders itself was a matter of some debate, but Thayer opted for 11.) Carrington, though, took the place of J. David Stern, who would outlive both Thayer and Carrington as well as the Society, not dying until 1971. He had quit the Society in a huff in the early 1940s, though, after Thayer wrote what Stern though were seditious columns in the magazine. Why Thayer waited five years to replace Stern is not clear—perhaps he thought he could entice him back—but it came in the years just after World War II, when Thayer was in a mood to organize the Society.

Two of the other mentions were prompted by books Carrington wrote: in Doubt 42 (October 1953), Thayer mentioned that Carrington had co-authored a book with Sylvia Muldoon on Astral Projection. And in Doubt 48 (April 1955) Thayer gave relatively effusive praise to Carrington's new book on Palladino: “MFS Eileen Garrett, publisher of Tomorrow, has published a new work by Honorary Founder Hereward Carrington. This is the American Seances with Eusapia Palladino. As older members will recall, Palladino put on the best and most convincing mediumistic show that the world has ever seen. Although Hereward was in on the tests, and wrote a big book about her in 1909, he still does not know how she accomplished some of her effects. These seances took place in 1909 and 1910, after the other book was written. For believers and non-believers in ‘spiritualism,’ this exciting data. From the Society $3.75.”

Carrington was also mentioned upon the death of Harry Price, a member and British ghost hunter. Thayer said that he was soliciting remembrances of Price from Carrington and Fodor. Whether he did or not—whether they responded or not—Doubt never published any such memorial to Price.

Besides the elevation to Honorary Founder, Carrington was esteemed once more by the Society—but as with every mention, it is unclear that Carrington had anything to do with Thayer’s Fortean club. (Presumably, he accepted the invitation to be an Honorary Founder, since Thayer did not add other people to the same station who did not respond or responded negatively, which shows that, at the very least, Carrington had a soft spot for Fort. Or Thayer.) In Doubt 32 (March 1951), Thayer wrote a bit titled “Hail, Carrington!”:

“Because Hereward Carrington, HFFS, was quoted in an interview as saying, ‘I am terribly disappointed by the ghosts around Los Angeles. They aren’t worth a tinker’s damn…”--the dean of psychic investigators was attacked in a two-age article by Ralph C. Pressing, editor of the Psychic Observer, issue of Nov. 25.

“Pressing and his wife are the bell-wethers of the table-tipping, tin-trumpet clan, publishers of the Psychic Observer and merchants in trumpets, luminous paint, Ouija boards, ‘Indian’ incense and ‘crystal’ balls. Not all Carrington’s published work in the past fifty years will stand up under searching Fortean criticism, but this attack by Pressing would make up for a good many lapses into faith. Let Forteans be known by the enemies they make.”

After Carrington died, Thayer wrote to his confidante Eric Frank Russell that he thought the natural successor would be Eric J. Dingwall. Thayer tendered the offer and Dingwall accepted, in April 1959, four months before Thayer himself would die. That same month’s issue of Doubt (#60), included an obituary for Carrington. “Sadly and solemnly,” Thayer wrote, “You must be informed that Hereward Carrington left us for his ultimate investigation of psychic phenomena last December 26.” Thayer was glad that he was never fully convinced of psychic phenomena, dismissing 98% of the claimants as frauds, but wanting to explore and explain the residual 2%: “That is why the Fortean Society has been proud of Hereward Carrington’s service as an Honorary Founder of the Society since 13 FS, 1943 old style.” (Thayer got that wrong: In 1943, Carrington was listed as an Accepted Fellow, eligible to become an Honorary Founder, but at that time the Fortean Society paperwork continued to list J. David Stern as a living Founder.) He then went on to praise Carrington’s successor:

“Since [about 1940], Dr. Dingwall has not only constantly added to his kudos by his own consistently Fortean approach to psychic science in Britain, but--at the death of Harry Price--still more dignities, honors and responsibilities gravitated upon his shoulders. In the next issue of DOUBT we shall have more details of the titles and labors of Dr. Eric J. Dingwall. At this time it is possible to say only that Dr. Dingwall has agreed to accept the post of Honorary Founder of the Fortean Society, vacated by our loss of Hereward.

“So if any of you get, ‘from the other side,’ the secret word that Hereward shared with Houdini, you will have to prove it to a very Solomon of a judge in Eric J. Dingwall.”

Carrington deserves a fuller treatment, perhaps a group biography of him, Price, Fodor, and Dingwall.