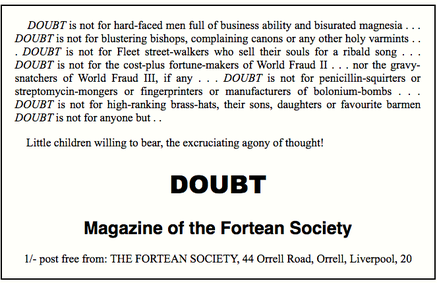

Ad for "Doubt" that ran in the "Fantasy Review" 1.2 (Apr-May 1947). This advertisement enticed Stanton to start reading the magazine.

Ad for "Doubt" that ran in the "Fantasy Review" 1.2 (Apr-May 1947). This advertisement enticed Stanton to start reading the magazine. A mostly mysterious Fortean.

Henry Kendall B. Stanton was born in 1924. I think. I do not know what the B stood for. He was born in England. I do not know who his parents were or if he had siblings. I do not know where he went to school, or the environment in which he grew up. He married Jacqueline Widgery in Exeter (Devon) England. I do not know when. They had at least one child—I think—a daughter named Yolanda. As far as I know, Stanton did not serve in World War II, though he would have been of age. I do not know why he missed out.

Stanton had a number of avocations I have found—but I do not know what he did to keep the family in noodles and socks. He had an interest in fantastic literature, reading, at least, “The Fantasy Review,” one of the post-War science fiction ‘zines, as English fandom was trying to re-establish itself on a firm footing. No later than 1950, he belonged to the British Interplanetary Society, whose membership overlapped with fandom, but was more focused, early on, in getting rockets into the air and, later, in supporting rocket and space research—that is to say, nuts and bolts science as opposed to fantastic science. (Arthur Clarke, among others, was both a science fictionist and a rocketeer.) He seems to have had an interest in the Masons, though I do not know if he belonged to a Lodge himself. He also collected coins from public houses, which his daughter would write about many years later.

Henry Kendall B. Stanton was born in 1924. I think. I do not know what the B stood for. He was born in England. I do not know who his parents were or if he had siblings. I do not know where he went to school, or the environment in which he grew up. He married Jacqueline Widgery in Exeter (Devon) England. I do not know when. They had at least one child—I think—a daughter named Yolanda. As far as I know, Stanton did not serve in World War II, though he would have been of age. I do not know why he missed out.

Stanton had a number of avocations I have found—but I do not know what he did to keep the family in noodles and socks. He had an interest in fantastic literature, reading, at least, “The Fantasy Review,” one of the post-War science fiction ‘zines, as English fandom was trying to re-establish itself on a firm footing. No later than 1950, he belonged to the British Interplanetary Society, whose membership overlapped with fandom, but was more focused, early on, in getting rockets into the air and, later, in supporting rocket and space research—that is to say, nuts and bolts science as opposed to fantastic science. (Arthur Clarke, among others, was both a science fictionist and a rocketeer.) He seems to have had an interest in the Masons, though I do not know if he belonged to a Lodge himself. He also collected coins from public houses, which his daughter would write about many years later.

As far as I can tell, Stanton spent most of his life in Exeter. It’s one of those cases of a person being born to the metropole and yet remaining fairly provincial. (Consider people whose horizon never goes beyond New York City.) That was where he was married. That was the address he used int he 1940s and 1950s. That was where he died.

Henry K. B. Stanton died in 1989.

I think.

*************

Stanton came to Fort the Society founded in his honor through science fiction and fantasy fandom. I do not know how much of fan he was—I haven’t seen his name noted in standard histories or ‘zines. But in 1947—when he was in his early 20s, according to my reconstruction of his biography—Stanton read “Fantasy Review,” edited by Walter Gillings. “Fantasy Review” commented on Fortean doings and sometimes advertised the Society. It was one of those advertisements that intrigued Stanton.

He wrote to Eric Frank Russell—as British Representative of the Society—asking for a copy of the latest issue of “Doubt,” after seeing the ad in volume 1, number 2. The letter itself is undated, but that issue of “Fantasy Review” is from April-May 1947, so he must have written his letter some time after that. There are subsequently a few (dated) letters preserved among Eric Frank Russell’s papers at the University of Liverpool, most of which are concerned with business, but nonetheless give insight into Stanton’s developing Forteanism. The next letter in series comes from the end of September 1947 and has him buying a copy of the “Books of Charles Fort” from Russell, which he saw advertised in “Doubt,”—indicating that Stanton had no idea what Forteanism was about when he subscribed to but was enticed by the ad, which read:

“DOUBT is not for hard-faced men full of business ability and bisurated magnesia . . . DOUBT is not for blustering bishops, complaining canons or any other holy varmints . . . DOUBT is not for Fleet street-walkers who sell their souls for a ribald song . . . DOUBT is not for the cost-plus fortune-makers of World Fraud II . . . nor the gravy-snatchers of World Fraud III, if any . . . DOUBT is not for penicillin-squirters or streptomycin-mongers or fingerprinters or manufacturers of bolonium-bombs . . . DOUBT is not for high-ranking brass-hats, their sons, daughters or favourite barmen DOUBT is not for anyone but . .

Little children willing to bear, the excruciating agony of thought!”

Russell most likely would have sent Doubt 17. It was intriguing enough, apparently, that in October Stanton ordered the back issues numbered 7, 8, 11, 12, 16. I do not know his financial situation, obviously, but this was a non-trivial outlay of funds in a short period of time for a new enthusiasm, so something clicked. Through 1948, he continued to send Russell payment for each single issue, rather than subscribing to the magazine or becoming a member. Sometime prior to December 1947 he had been in correspondence with Tiffany Thayer, as well, who sent him a membership application—but apparently no instructions, so in December Stanton asked Russell if he could give his dues to him, obviating the difficulty of sending money internationally. I suppose Russell said yes, but for whatever reason Stanton continued to pay for each issue separately.

Despite the insistence on a relationship rather than subscription, there were hiccups. Stanton paid for issue 22 in October of 1948, and then wrote again asking in November, since he had not received acknowledgment, or the Doubt. It came a few days later, and Stanton wrote to note this—and also ask if Russell had a copy of the Society’s 13-month calendar that he could spare. Apparently, he (charmingly) believed that the delay was because Thayer followed an obscure publishing schedule, when in fact, Thayer just followed an erratic one. At least, that’s my interpretation of Stanton’s asking for the calendar on the heels of the delay.

Also delayed was his copy of “The Books of Charles Fort,”—which was standard. Thayer continually insisted they should be easily obtainable in Britain because he had deals with various bookstores. And yet member after member had difficulty. In Stanton’s case, the books he had asked for—and paid for—in September 1947 reached him at the end 1948, or thereabouts. On the 5th of January 1949 he wrote to Russell—paying for issue 23—and noted he had recently received the Books, and read them. “Much that was obscure in past numbers of “Doubt” is now clear to me. He certainly wielded a vitriolic pen!” Clearly, actually reading the Books deepened Stanton’s pleasure, and he wrote asking for more back issues—1, 2, 4, 5, 13, 15. These, he said, were needed to complete his set, which further suggested that he had bought other issues from other people: that he was reading out to a larger Fortean community.

No more correspondence between Stanton and Russell—if such exists—is preserved at Liverpool. There are a few stray remarks about him in the correspondence between Thayer and Russell. Thayer acknowledged him paying his dues, for example, and asking another time if he had paid them—so Stanton must have gotten over his need to pay for each issue individually. He also seems to have purchased a few other items through the Society, probably books, as Thayer dunned him once in 1951: $2.75 for something, but Thayer said he could not remember once.

If this correspondence can be taken as a reflection of Stanton’s interest in Forteanism, then it was not an enthusiasm that lasted very long. He expressed his interest in 1947. There were no more mentions of him after 1952. That’s five years, which isn’t nothing, but also isn’t really substantial. His one contribution to the Society came in Doubt 27 (Winter 1949), right in the heart of his Fortean adventure. He sent in a clipping—along with many other Forteans—about a fish fall in Marksville, Louisiana. This was a pivotal moment in the Forteans interest in rains of fishes. It renewed interest in the subject by meteorologists and was America itself, well covered by the press, difficult to ignore—hard to be damned.

Which suggests that Stanton’s interest in Forteanism ran along conventional lines—the usual Fortean subjects. But that’s not the case.

On 21 December 1947—referring apparently to the correspondence that got Thayer to send Stanton a membership application—Thayer wrote to Russell, “Have you worked on Henry K B Stanton, Lucas Avenue, Exeter, Devon ENGLAND. He asks for dope on Grindell Matthews as if he had a right to, but we don’t have Stanton listed as an MFS.” A few months later, on 19 June 1948, Stanton made the same request of Russell as he had of Thayer: he wanted information on Grinder Matthews because he wanted to refute the claim of a publisher that Matthews was a fraud and a commercial adventurer. The real heart of Stanton’s Fortean career, then, was not fish falls in (for him) far-off Louisiana, but the home-grown (if much older) popularizer of death rays.

Yep, death rays.

Harry Grindell-Matthews was an inventor, born in 1880. In the early part of the 20th-century, he claimed to have made number of breakthrough inventions, some of which seem to have been frauds others puffery. Later, in the 1930s, he went through similar trials and tribulations. But he is most known for his claims of the 1920s. That was when he reported to have invented an electric ray that would stop engines. The claim caught the attention of Britain’s military, but all the demonstrations came to naught.

The idea seems outlandish—it is the stuff of Buck Rogers and Hugo Gernsback—but was not without its supporters. Into the 1930s, there were concerns that Germany had its own death ray. When British engineers revisited the problem then, amid concerns of a Nazi invasion, Robert Watson-Watt showed, via calculation, that such a device was impossible. But in the course of doing his research, he noted that radio waves might be able to detect air craft—the first seeds of the radar technology which would be so important to Britain during World War II.

Stanton, clearly, was taking no solace in the side effects of death ray research. He wanted to venerate Grinnell-Matthews himself. The inventor had died several years before, in 1941, from a heart attack. For whatever reasons, Stanton was looking to become a standard-bearer in a quixotic attack on orthodox electrical engineering.

I do not know what ever became of Stanton’s planned campaign. Probably nothing. At least, I have not come across any mention of it.

Like his Forteanism—like death rays themselves—it soon enough disappeared, and was forgotten.

Henry K. B. Stanton died in 1989.

I think.

*************

Stanton came to Fort the Society founded in his honor through science fiction and fantasy fandom. I do not know how much of fan he was—I haven’t seen his name noted in standard histories or ‘zines. But in 1947—when he was in his early 20s, according to my reconstruction of his biography—Stanton read “Fantasy Review,” edited by Walter Gillings. “Fantasy Review” commented on Fortean doings and sometimes advertised the Society. It was one of those advertisements that intrigued Stanton.

He wrote to Eric Frank Russell—as British Representative of the Society—asking for a copy of the latest issue of “Doubt,” after seeing the ad in volume 1, number 2. The letter itself is undated, but that issue of “Fantasy Review” is from April-May 1947, so he must have written his letter some time after that. There are subsequently a few (dated) letters preserved among Eric Frank Russell’s papers at the University of Liverpool, most of which are concerned with business, but nonetheless give insight into Stanton’s developing Forteanism. The next letter in series comes from the end of September 1947 and has him buying a copy of the “Books of Charles Fort” from Russell, which he saw advertised in “Doubt,”—indicating that Stanton had no idea what Forteanism was about when he subscribed to but was enticed by the ad, which read:

“DOUBT is not for hard-faced men full of business ability and bisurated magnesia . . . DOUBT is not for blustering bishops, complaining canons or any other holy varmints . . . DOUBT is not for Fleet street-walkers who sell their souls for a ribald song . . . DOUBT is not for the cost-plus fortune-makers of World Fraud II . . . nor the gravy-snatchers of World Fraud III, if any . . . DOUBT is not for penicillin-squirters or streptomycin-mongers or fingerprinters or manufacturers of bolonium-bombs . . . DOUBT is not for high-ranking brass-hats, their sons, daughters or favourite barmen DOUBT is not for anyone but . .

Little children willing to bear, the excruciating agony of thought!”

Russell most likely would have sent Doubt 17. It was intriguing enough, apparently, that in October Stanton ordered the back issues numbered 7, 8, 11, 12, 16. I do not know his financial situation, obviously, but this was a non-trivial outlay of funds in a short period of time for a new enthusiasm, so something clicked. Through 1948, he continued to send Russell payment for each single issue, rather than subscribing to the magazine or becoming a member. Sometime prior to December 1947 he had been in correspondence with Tiffany Thayer, as well, who sent him a membership application—but apparently no instructions, so in December Stanton asked Russell if he could give his dues to him, obviating the difficulty of sending money internationally. I suppose Russell said yes, but for whatever reason Stanton continued to pay for each issue separately.

Despite the insistence on a relationship rather than subscription, there were hiccups. Stanton paid for issue 22 in October of 1948, and then wrote again asking in November, since he had not received acknowledgment, or the Doubt. It came a few days later, and Stanton wrote to note this—and also ask if Russell had a copy of the Society’s 13-month calendar that he could spare. Apparently, he (charmingly) believed that the delay was because Thayer followed an obscure publishing schedule, when in fact, Thayer just followed an erratic one. At least, that’s my interpretation of Stanton’s asking for the calendar on the heels of the delay.

Also delayed was his copy of “The Books of Charles Fort,”—which was standard. Thayer continually insisted they should be easily obtainable in Britain because he had deals with various bookstores. And yet member after member had difficulty. In Stanton’s case, the books he had asked for—and paid for—in September 1947 reached him at the end 1948, or thereabouts. On the 5th of January 1949 he wrote to Russell—paying for issue 23—and noted he had recently received the Books, and read them. “Much that was obscure in past numbers of “Doubt” is now clear to me. He certainly wielded a vitriolic pen!” Clearly, actually reading the Books deepened Stanton’s pleasure, and he wrote asking for more back issues—1, 2, 4, 5, 13, 15. These, he said, were needed to complete his set, which further suggested that he had bought other issues from other people: that he was reading out to a larger Fortean community.

No more correspondence between Stanton and Russell—if such exists—is preserved at Liverpool. There are a few stray remarks about him in the correspondence between Thayer and Russell. Thayer acknowledged him paying his dues, for example, and asking another time if he had paid them—so Stanton must have gotten over his need to pay for each issue individually. He also seems to have purchased a few other items through the Society, probably books, as Thayer dunned him once in 1951: $2.75 for something, but Thayer said he could not remember once.

If this correspondence can be taken as a reflection of Stanton’s interest in Forteanism, then it was not an enthusiasm that lasted very long. He expressed his interest in 1947. There were no more mentions of him after 1952. That’s five years, which isn’t nothing, but also isn’t really substantial. His one contribution to the Society came in Doubt 27 (Winter 1949), right in the heart of his Fortean adventure. He sent in a clipping—along with many other Forteans—about a fish fall in Marksville, Louisiana. This was a pivotal moment in the Forteans interest in rains of fishes. It renewed interest in the subject by meteorologists and was America itself, well covered by the press, difficult to ignore—hard to be damned.

Which suggests that Stanton’s interest in Forteanism ran along conventional lines—the usual Fortean subjects. But that’s not the case.

On 21 December 1947—referring apparently to the correspondence that got Thayer to send Stanton a membership application—Thayer wrote to Russell, “Have you worked on Henry K B Stanton, Lucas Avenue, Exeter, Devon ENGLAND. He asks for dope on Grindell Matthews as if he had a right to, but we don’t have Stanton listed as an MFS.” A few months later, on 19 June 1948, Stanton made the same request of Russell as he had of Thayer: he wanted information on Grinder Matthews because he wanted to refute the claim of a publisher that Matthews was a fraud and a commercial adventurer. The real heart of Stanton’s Fortean career, then, was not fish falls in (for him) far-off Louisiana, but the home-grown (if much older) popularizer of death rays.

Yep, death rays.

Harry Grindell-Matthews was an inventor, born in 1880. In the early part of the 20th-century, he claimed to have made number of breakthrough inventions, some of which seem to have been frauds others puffery. Later, in the 1930s, he went through similar trials and tribulations. But he is most known for his claims of the 1920s. That was when he reported to have invented an electric ray that would stop engines. The claim caught the attention of Britain’s military, but all the demonstrations came to naught.

The idea seems outlandish—it is the stuff of Buck Rogers and Hugo Gernsback—but was not without its supporters. Into the 1930s, there were concerns that Germany had its own death ray. When British engineers revisited the problem then, amid concerns of a Nazi invasion, Robert Watson-Watt showed, via calculation, that such a device was impossible. But in the course of doing his research, he noted that radio waves might be able to detect air craft—the first seeds of the radar technology which would be so important to Britain during World War II.

Stanton, clearly, was taking no solace in the side effects of death ray research. He wanted to venerate Grinnell-Matthews himself. The inventor had died several years before, in 1941, from a heart attack. For whatever reasons, Stanton was looking to become a standard-bearer in a quixotic attack on orthodox electrical engineering.

I do not know what ever became of Stanton’s planned campaign. Probably nothing. At least, I have not come across any mention of it.

Like his Forteanism—like death rays themselves—it soon enough disappeared, and was forgotten.