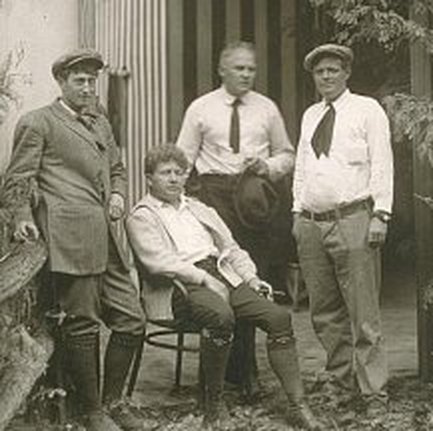

Wilson (left) with James Hopper, George Sterling, and Jack London.

Wilson (left) with James Hopper, George Sterling, and Jack London. Harry Leon Wilson is another founder who became disenchanted with the Fortean Society—though he was never much of a member at all.

Like a number of the other founders—Dreiser, Hecht, Rascoe, and Tarkington—Wilson was a Midwesterner who found his way into artistic circles. He was born in Oregon, Illinois on the first of May, 1867, and grew up disliking the restrictive religion of the day. His father owned a newspaper, and Wilson learned to set type at a young age. Turning sixteen, he left home and used his stenography skills working for the Union Pacific and also for interviewing pioneers for the Bancroft History Company. Over the next several years, he moved about the west, dabbling in Spiritualism and starting to write his own material—he sent a piece to Puck, which ran in the December 1886 issue. Puck was a satirical paper, something like The Onion of its day, and Wilson continued to send in stories over the year,s including a burlesque of H. Rider Haggard’s “She” he titled “Her.” In 1886, he moved to New York and took a job as assistant to the editor. Six years later, when the then-editor died, Wilson assumed his position until 1902.

In New York, Wilson shed his Midwestern values and replaced them with Bohemian ones. In 1899, he married for the first time, but apparently continued having affairs and drinking a lot. The marriage ended the following year. He tired of New York City, though, and decided the best way out was to make money from a novel—and so he wrote and published The Spenders in 1902. The advance allowed him to move and to marry Rose O’Neill, whom he had met at Puck and who had illustrated his book. They settled in the Ozarks. That same year he likely met Booth Tarkington. Wilson’s next two books reflected his disenchantment with American religion: Lions of the Lord mocked Mormon religion, and The Seeker went after the hypocrisy of mainstream faith which, in the age of science, no longer had a firm place. The novel—part well-observed story, part polemic—told of two brothers, and their fates, an honorable atheist and a conniving Christian. It was well received by H. G. Wells, who was one of Wilson’s early influences, along with Mark Twain and Ambrose Bierce. (All were contemporaries.)

Wilson’s second marriage only lasted until 1907, but in the meantime he teamed up with Booth Tarkington to write a series of plays for the provincial theater circle, often called “The Road.” They had a hit in 1908 with “The Man From Home,” about a provincial character, which set the framework for their subsequent plays. Wilson’s existence was peripatetic at the time. The playwriting came to an end in 1910, for both personal and structural reasons. Both Wilson and Tarkington were drinking heavily, and Tarkington was having marital problems, which interfered with their collaboration. Plus, tastes were changing, from the melodrama in which they specialized to a more realist style identified with Ibsen and Shaw. The Road was closing, pushed out by movie theaters and radios and Broadway: plays that went on tour increasingly needed to make it on Broadway first, and Wilson did not know how to write those kinds of plays.

In the fall of 1910, Wilson settled into a Bohemian community centered around Carmel, California. (This community would become important to the later development of Forteanism in the San Francisco Bay Area.) Forty-five and financially stable, he befriended Mary Austin, George Sterling, and Jack London, among others. (Ambrose Bierce, who had connections here, had gone missing in 1906, disappeared in Mexico.) He courted a young woman named Helen Cook, who had also attracted the attention of Sinclair Lewis, the future Nobel Prize winner and habitué of the Carmel social circle. Helen chose to marry Wilson. They wed in 1912. She was 17.

Over the next decades, Wilson settled more firmly ingot he community and experienced his greatest literary success. He had two children, Henry Leon Wilson Jr. in 1913, Helen Charis Wilson in 1914. He published two books that brought him great acclaim, Bunker Bean, which owed a great debt to H. G. Wells’s Kipps, and Ruggles of Red Gap, which had an English butler suddenly forced to serve American parvenus and introduced his most enduring character, Ma Pettengill. . Both were serialized in the Saturday Evening Post, which became Wilson’s authorial home more than a decade before it hosted that other great Fortean Alexander Woollcott. Wilson’s style was developing—it continued to be closely observed, but now found humor and appreciation in its rural characters, even when it did not agree with them. Ma Pettengill offered homespun wisdom as a counterpoint to the new ideas associated with a modernizing America. As was the case with his playwriting, Wilson’s novel writing also followed a pattern, according to his biographer George Kummer, who said most stories featured a struggling little man eventually rescued by a mother figure. While Dreiser’s writing, with its sex, was championed by new-style realists such as H. L. Mencken, and Tarkington, with its sex muted but realism still there, won plaudits from the older realists such as William Dean Howells, Wilson’s affectionate but clear-eyed portrayal of American rurals received acclaim from both. Kummer again: In 1918, Wilson “was probably the only popular writer to pleas both Howells and Mencken, critics who represented opposite poles of American taste. Between these extremes were thousands of readers who enjoyed the doings of Bunker Bean, Ruggles and Ma Pettengill.” Wilson himself remained allergic to the writings of Sinclair Lewis. He asked Tarkington:

“Why can’t I read Sinclair Lewis with any comfort? Is it merely because a few days’ personal encounter left me disliking him?”

Wilson thought Lewis’s 1920 Main Street filled with the author’s “contemptuous smarty superiority.” When Lewis won the Novel Prize in 1930, neither Wilson nor Dreiser—whom Lewis accused of plagiarism—were very happy.

On the success of Ruggles of Red Gap, Wilson took a year—1917—off writing and indulged a budding interest in philosophy and solidified his thinking on general matters. Like Dreiser and Mencken, he was strongly influenced by Herbert Spencer (a philosophical favorite because his writing had heft without being unreadable). Competition, he felt, was the method through which the ‘unknowable’ (that thing behind all life) worked, pitting people against people, races against races. Like Dreiser, he thought that free will was an illusion—a perfect one, making people feel they were in charge, so they kept going, even as they weren’t. A Malthusian, too, he assumed the Chinese would inherit the earth as they could handle the stresses of an overpopulated planet. He rejected imperialism—as too bureaucratic—and celebrated the virtues of unconstrained capitalism.

This new philosophical bent infected his writing, as he return dot his craft. At the end of the decade he wrote a few war stories, and also injected philosophy into his Ma Pettengill stories. “The Porch Wren,” for instance, had Ma waxing eloquent on the age of the earth and the study of evolution—as well as on matters of the heart (and pocketbook). Kummer reads this short story as something new in American letters, a burlesque of scientific thought different in kind from that offered by Twain and others. I’m not so sure it is as unique as he says, but it does give an idea of the drift in Wilson’s thought. In 1919, Wilson also wrote a play for the Bohemian Club (in San Francisco) called “Life,” which made the point—a point he would come to repeatedly—that life is a card game we are all destined to lose. (But from a cosmic perspective everything was copacetic; even if humans scotch up life on earth, it would continue on other planets.) That same year he started serializing “The Wrong Twin” in The Saturday Evening Post, which featured a tramp printer, Dave Cowan, who was a Spencerian. And the following year he published in the same magazine an article mocking spiritualism. But done lightly enough that The Order of Christian Mystics enjoyed it. Wilson had a deft touch for pointing out the absurdities of America’s metaphysical religions. He started a chapter in his novel The Wrong Twin thusly:

“Archeologists of a future age will doubtless, in their minute explorations of this region, come upon the petrified remains of golf balls in such number as will occasion learned dispute. Found so profusely and yet so far from any known course, they will perhaps give rise to wholly erroneous surmises. Prefacing his paper with a reference to lost secrets once possessed by other ancients, citing without doubt that the old Egyptians knew how to temper the soft metal of copper, a certain scientist will profoundly deduce from this deposit of balls, far from the vestiges of the nearest course, that people of this remote day possessed the secret of driving a golf ball three and a half miles, and he will perhaps moralize upon the degeneracy of his own times, when the longest drive will doubtless not exceed a scant mile.” (180).

Of course, the joke could be seen at the expense of scientists, too.

It was around this time that Wilson first encountered Fort’s writings, though exactly when and how is not known—even as it is subject of firm declamations. Sam Moskowitz, the science fiction fan and critic of Forteanism, wrote,

“Booth Tarkington induced Henry [sic] Leon Wilson, famed author of the Ruggles of Red Gap (with whom he collaborated on the play The Man from Home, produced in 1907, which ran for six years), to read Fort. The result was explosive. Wilson’s subsequent novel, The Wrong Twin, found a philosophic tramp printer spouting Fort’s wildest theories at the drop of a hat throughout. Perhaps Wilson should have been suspect when he wrote Bunker Bean in 1912, a book in which the lead character buys a mummy which he claims was himself in a previous incarnation.” [Sam Moskowitz, Strange Horizons, 1976, p. 239]

But this description makes no sense chronologically. Wilson’s “The Wrong Twin” was serialized in The Saturday Evening Post for ten issues starting in November 1919. Fort’s Book of The Damned was not published until 1 December 1919. What’s more, Cowan never spouts Fort’s theories. His vision of life is purely Spencerian—although he is skeptical enough to admit there’s a catch he has not quite figured out.

“There’s life for you,” Cowan says to one of his twin sons. “Life has to live on life, humans same as dogs. Life is something that keeps tearing itself down and building itself up again; everybody killing something else and eating it. … Humans are the best killers of all,” he continued, “That’s the reason they came up from monkeys, and got civilized so they were neckties and have religion and post offices and all such.”

He rhapsodizes about the age of the universe and the vast distances between suns. These are not Fortean thoughts at all! Either Moskowitz could not tell the difference between Herbert Spencer and Charles Fort, or he never read “The Wrong Twin” at all.

Nonetheless, there is a shadow of truth in what he has to say. It is likely that Tarkington turned on Wilson to Fort’s writings. Tarkington noted (in the introduction he wrote to New Lands), “A few years ago I had one of those pleasant illnesses that permit the patient to read in bed for several days without self-reproach; and I sent down to a bookstore for whatever might be available upon criminals, crimes and criminology. Among the books brought me in response to this morbid yearning was one with the title, The Book of the Damned.” We can date this illness with some degree of accuracy, thanks to Tarkington’s correspondence with Wilson. On 8 February 1920, Tarkington wrote Wilson to say that he had suffered the flu and was forced to bed for a few days of reading. He did not mention Fort, but this is likely when he read The Book of the Damned—early February 1920. (By this point, the tenth and final part of Wilson’s ‘The Wrong Twin’ had appeared in The Saturday Evening Post.)

Unfortunately, very soon after this letter there’s a long break in the correspondence between the two men, lasting until 1923, just before Tarkington wrote the introduction to Fort’s second book—and so there is no way of saying for certain that Tarkington introduced Wilson to Fort’s writings. But there was one bit of correspondence that came through during the hiatus. In October 1920 Tarkington sent a short note to Wilson advising he was sending him “some stuff.” This package may very well have included The Book of the Damned. At any rate, even if Wilson did not read Fort this early, he was surely introduced to him by Tarkington’s introduction to New Lands—so likely sometime between October 1920 and October 1923.

By the mid-1920s, though, Wilson had other matters on his mind. His marriage fell apart, resulting in a divorce in 1927. He fled to to Portland, Oregon, for two years. His children, Leon and Charis (both dropped their parental first names) saw very little of either Harry or Helen. He returned o Carmel in 1929, while Charis spent much of her time with her grandmother and an aunt, part of the San Francisco arts community. She followed in her father’s Bohemian footsteps, experimenting sexually before meeting and coupling with the photographer Edward Weston. Leon eventually drifted to Hollywood to try to become a writer.

In November 1930, Tiffany Thayer began preparing for the publication of Fort’s third book, Lo!, by starting—at the suggestion of J. David Stern—the Fortean Society. Harry Leon Wilson was not on the original list of members. But in January, as momentum—and publicity—increased, his name became attached to the project. A letter dated 22 January from Thayer drumming attention for the Society noted that Wilson wanted to join. Whether this was at his instigation, Thayer’s, or even Booth Tarkington’s is not known. The first meeting of the Fortean Society was held four days later; Wilson wasn’t there, but Thayer announced that he had joined the Society. After reading Lo!, he wrote Thayer:

“I am today returning New Lands and am sending my copy of Lo! to an inquiring friend. Also I enclose a small contribution to the Cause.

Fort is highly exciting to me. I cannot share, as fellow host, quite all of what he somewhere speaks of as his ‘bizarre hospitalities,’ but I do greatly enjoy going to his parties.

In early infancy he seems to have been bitten by a rabid astronomer--and more venom to him.

As I go down into the vale of years I grow more and more suspicious of all certainties. Perhaps in another dozen years some one will be attacking Fort’s certainties and I’ll be for that guy, too.

A note from Milliken the other day--’99/100 of what is written on four dimensions is merely nonsense.’ It’s up to C.F. to take care of that minute reminder [sic]. With Einstein as the North Pole and Fort as the South, maybe we can get somewhere. I shall look forward to the next assault on old walls.” (The Fortean Society Magazine 8 (Dec. 1943): 12.”

The letter is interesting because it suggests that Wilson had not—or did not remember having—read New Lands, which suggests that his enthusiasm for Fort, whatever he says in the letter, was relatively subdued. It is also worth noting that Wilson yoked Fort and Einstein, a pairing that Thayer resisted for many years.

But however serious Wilson’s interest in Fort was after the founding of the Society, he soon had other, more serious matters with which to contend. In June 1932—a month after Fort died—he was in a serious car accident, which set off a series of medical problems that were to consume the next seven years until he died 28 June 1939. He had high blood pressure. He had a series of strokes. Wilson thought of writing one final work, to be called “The Stranger,” a kind of science fiction story in which an alien comes to earth and contrasts his civilization with that of earth’s, to point out the absurdities of our lives. He couldn’t pull it off, though, no longer able to concentrate well enough to write. Leon and Charis begged Tarkington for financial help—Wilson had been profligate with his fortune and ended up in debt—which Tarkington gladly supplied. Wilson’s mind turned to reflections on his literary past. He no longer though much of philosophy, telling H. L. Mencken,

“I loathe the words metaphysics and mysticism and am adding ‘philosophy’ to my proscribed list. To hell with ‘Philosophy!’ obscuring the obvious with noisy words.”

He appreciated that Twain could be great, but also that he had many weaknesses, as did H. G. Wells, telling Leon,

“And so different in his faults and failing from another man I once thought pretty big--H.G. Wells. To me now this man is pretty pathetic. A lower-middle-class Briton showing off before his social superiors. See his God-awful tripe in the June Harpers. If you can read one paragraph of it with understanding I shall ask you to return all my keepsakes and to avoid speaking when we meet. My dirty, low-down suspicion is that Wells, with his Cockney posing as one with a gift for putting the world right, is hoping for nothing less than a knighthood, than which a Briton of his class can imagine nothing more sublime. And at least old man Clemens couldn’t have been bought with anything tawdry.”

Only Ambrose Bierce continued to inspire him—and may have been a spark for “The Stranger.” He told Leon Bierce’s

“short stories are superb. I really believe no better ones were ever written. And I couldn’t name any as good. He is remarkable for his polished economy of words.”

(It is worth noting that in the same letter Wilson mentioned Bierce’s disappearances, but not Fort’s writing about that disappearance.)

If life was a card game, he was losing—but not without taking a little satisfaction. He wrote Tarkington:

“And I haven’t had a drink for a year. That slap sort of incited my blood pressure and two M.D’s, close-herding me, struck out all alcohol, after I’d been imbibing fluently for forty-five years. Funny, but I let the hard liquor go with never a yearning. I handle it, serve it, almost every day, make cocktails and such, and probably will never again want even a sip. But I do miss the wine. I’d just acquired the tail end of the wine cellar of a famous old restaurant in S.F. and I often go into the basement to stand wistful in the presence of a couple hundred quarts of authentic Burgundy, Chablis, Moselle and so on, but all I can do is give it away to people so unappreciative I know they’d rather have the current Scotch or even gin with a bar sinister. And I’m not even let to have coffee. But once a week I debauch myself with the real stuff. Drink two cups and am inebriated perfectly, as by four stiff high-balls, joyous, approachable, ready to grant any favor. So far the M.D’s haven’t found me out.”

In September, Harry Leon Wilson received a letter from Tiffany Thayer, along with a copy of the first issue of the Fortean Society Magazine. Wilson had not been involved with the legal wrangling around the ownership of Fort’s notes, so had no idea that a Society was in the works, and it seems that he wrote to Tarkington asking him what the deal was. Tarkington responded in October. His penmanship by this—never great to begin with—was horrid, and some of the words are indecipherable, but the gist is clear:

“Gold--I’d just written you & sent you a book when there came your letter. Hasten to dispense any suspicions you may have about my friendship for, or with, Mr. Tiffany T. Never see the bird. Years ago some people, no acquaintances of mine and [] this T.T. formed the “Fortean Soc.” and I signed up by mail, as understood the purpose was to be of use to that extraordinary man, Charles Fort, attract notice to his writings by giving a dinner for him, etc. (Fort was a great fellow--disappointed in me because it was a more literary than scientific interest in his works, he wrote me he’d discovered a terrific gulf in some constellation, a trillion mile vacuum, and had named it ‘Tarkington Gulf.’) I never saw [a]live; he used to live with Dreiser. Well, this summer Mrs. Fort’s lawyer (Fort’s widow’s) wrote me T.T, withheld all of Fort’s papers--said they belonged to the Fortean Soc. and wouldn’t turn ‘em in--and asked me (the lawyer did) to make a statement that the Soc. was extinct and the widow should have the papers. I did. Heard nothing more until rec’d copy of the 1st number of the mag, which brought me some letters from []. No correspondence with T.T., who seems to be using me pretty freely. He’ll blow up pretty soon, I’d think, Evidently use of the horse [‘s] daughter.”

In short, Wilson had no interest in Thayer or the Fortean Society.

The feeling was not reciprocated, though: Thayer loved Wilson’s writings. Thayer’s 1938 novel “Little Dog Lost” was his most autobiographical: about a Hollywood script writer who, longing for a life lived by one’s own wits and strength, experiences an identity crisis. He wonders if he could ever find a “good loose trade” like Dave Cowan. He cannot, but comes up with a compromise: he’ll publish a magazine. This was Merle’s solutions, and shown to be bad in “The Wrong Twin,” but John Smith—Thayer’s alter ego—thinks the project will work if he models it on Wilson’s run at “Puck”: a satirical magazine that shows how ridiculous the world has become. Thayer did this in real life with “The Fortean Society Magazine.”

And he insisted that Wilson, however lightly connected to Fort he might be, was an exemplar of Forteanism. Wilson was only twice mentioned in the Fortean Society Magazine, the first being notice of his death, and the second an encomium to him: In the December 1943 issue, Thayer published the letter that Wilson had sent him as well as a long excerpt from “The Wrong Twin” which reflected Dave Cowan’s thoughts on life. (Perhaps this is where Moskowitz got the idea that Dave Cowan was spouting Fortean theories.) Thayer added:

“Harry Leon Wilson towered over all his contemporary writers, the chiefest literary talent this country has produced since Mark Twain. Neither George Ade, nor Frank Norris, nor Sinclair Lewis could touch him; and Forteans who have not read Ma Pettengill, Merton of the Movies, Boss of Little Arcady, Bunker Bean and the Wrong Twin, quoted above, are advised to treat themselves promptly.”

It seems quite clear the Fortean Society wanted Harry Leon Wilson far more than Wilson wanted to be associated with the Society.

Like a number of the other founders—Dreiser, Hecht, Rascoe, and Tarkington—Wilson was a Midwesterner who found his way into artistic circles. He was born in Oregon, Illinois on the first of May, 1867, and grew up disliking the restrictive religion of the day. His father owned a newspaper, and Wilson learned to set type at a young age. Turning sixteen, he left home and used his stenography skills working for the Union Pacific and also for interviewing pioneers for the Bancroft History Company. Over the next several years, he moved about the west, dabbling in Spiritualism and starting to write his own material—he sent a piece to Puck, which ran in the December 1886 issue. Puck was a satirical paper, something like The Onion of its day, and Wilson continued to send in stories over the year,s including a burlesque of H. Rider Haggard’s “She” he titled “Her.” In 1886, he moved to New York and took a job as assistant to the editor. Six years later, when the then-editor died, Wilson assumed his position until 1902.

In New York, Wilson shed his Midwestern values and replaced them with Bohemian ones. In 1899, he married for the first time, but apparently continued having affairs and drinking a lot. The marriage ended the following year. He tired of New York City, though, and decided the best way out was to make money from a novel—and so he wrote and published The Spenders in 1902. The advance allowed him to move and to marry Rose O’Neill, whom he had met at Puck and who had illustrated his book. They settled in the Ozarks. That same year he likely met Booth Tarkington. Wilson’s next two books reflected his disenchantment with American religion: Lions of the Lord mocked Mormon religion, and The Seeker went after the hypocrisy of mainstream faith which, in the age of science, no longer had a firm place. The novel—part well-observed story, part polemic—told of two brothers, and their fates, an honorable atheist and a conniving Christian. It was well received by H. G. Wells, who was one of Wilson’s early influences, along with Mark Twain and Ambrose Bierce. (All were contemporaries.)

Wilson’s second marriage only lasted until 1907, but in the meantime he teamed up with Booth Tarkington to write a series of plays for the provincial theater circle, often called “The Road.” They had a hit in 1908 with “The Man From Home,” about a provincial character, which set the framework for their subsequent plays. Wilson’s existence was peripatetic at the time. The playwriting came to an end in 1910, for both personal and structural reasons. Both Wilson and Tarkington were drinking heavily, and Tarkington was having marital problems, which interfered with their collaboration. Plus, tastes were changing, from the melodrama in which they specialized to a more realist style identified with Ibsen and Shaw. The Road was closing, pushed out by movie theaters and radios and Broadway: plays that went on tour increasingly needed to make it on Broadway first, and Wilson did not know how to write those kinds of plays.

In the fall of 1910, Wilson settled into a Bohemian community centered around Carmel, California. (This community would become important to the later development of Forteanism in the San Francisco Bay Area.) Forty-five and financially stable, he befriended Mary Austin, George Sterling, and Jack London, among others. (Ambrose Bierce, who had connections here, had gone missing in 1906, disappeared in Mexico.) He courted a young woman named Helen Cook, who had also attracted the attention of Sinclair Lewis, the future Nobel Prize winner and habitué of the Carmel social circle. Helen chose to marry Wilson. They wed in 1912. She was 17.

Over the next decades, Wilson settled more firmly ingot he community and experienced his greatest literary success. He had two children, Henry Leon Wilson Jr. in 1913, Helen Charis Wilson in 1914. He published two books that brought him great acclaim, Bunker Bean, which owed a great debt to H. G. Wells’s Kipps, and Ruggles of Red Gap, which had an English butler suddenly forced to serve American parvenus and introduced his most enduring character, Ma Pettengill. . Both were serialized in the Saturday Evening Post, which became Wilson’s authorial home more than a decade before it hosted that other great Fortean Alexander Woollcott. Wilson’s style was developing—it continued to be closely observed, but now found humor and appreciation in its rural characters, even when it did not agree with them. Ma Pettengill offered homespun wisdom as a counterpoint to the new ideas associated with a modernizing America. As was the case with his playwriting, Wilson’s novel writing also followed a pattern, according to his biographer George Kummer, who said most stories featured a struggling little man eventually rescued by a mother figure. While Dreiser’s writing, with its sex, was championed by new-style realists such as H. L. Mencken, and Tarkington, with its sex muted but realism still there, won plaudits from the older realists such as William Dean Howells, Wilson’s affectionate but clear-eyed portrayal of American rurals received acclaim from both. Kummer again: In 1918, Wilson “was probably the only popular writer to pleas both Howells and Mencken, critics who represented opposite poles of American taste. Between these extremes were thousands of readers who enjoyed the doings of Bunker Bean, Ruggles and Ma Pettengill.” Wilson himself remained allergic to the writings of Sinclair Lewis. He asked Tarkington:

“Why can’t I read Sinclair Lewis with any comfort? Is it merely because a few days’ personal encounter left me disliking him?”

Wilson thought Lewis’s 1920 Main Street filled with the author’s “contemptuous smarty superiority.” When Lewis won the Novel Prize in 1930, neither Wilson nor Dreiser—whom Lewis accused of plagiarism—were very happy.

On the success of Ruggles of Red Gap, Wilson took a year—1917—off writing and indulged a budding interest in philosophy and solidified his thinking on general matters. Like Dreiser and Mencken, he was strongly influenced by Herbert Spencer (a philosophical favorite because his writing had heft without being unreadable). Competition, he felt, was the method through which the ‘unknowable’ (that thing behind all life) worked, pitting people against people, races against races. Like Dreiser, he thought that free will was an illusion—a perfect one, making people feel they were in charge, so they kept going, even as they weren’t. A Malthusian, too, he assumed the Chinese would inherit the earth as they could handle the stresses of an overpopulated planet. He rejected imperialism—as too bureaucratic—and celebrated the virtues of unconstrained capitalism.

This new philosophical bent infected his writing, as he return dot his craft. At the end of the decade he wrote a few war stories, and also injected philosophy into his Ma Pettengill stories. “The Porch Wren,” for instance, had Ma waxing eloquent on the age of the earth and the study of evolution—as well as on matters of the heart (and pocketbook). Kummer reads this short story as something new in American letters, a burlesque of scientific thought different in kind from that offered by Twain and others. I’m not so sure it is as unique as he says, but it does give an idea of the drift in Wilson’s thought. In 1919, Wilson also wrote a play for the Bohemian Club (in San Francisco) called “Life,” which made the point—a point he would come to repeatedly—that life is a card game we are all destined to lose. (But from a cosmic perspective everything was copacetic; even if humans scotch up life on earth, it would continue on other planets.) That same year he started serializing “The Wrong Twin” in The Saturday Evening Post, which featured a tramp printer, Dave Cowan, who was a Spencerian. And the following year he published in the same magazine an article mocking spiritualism. But done lightly enough that The Order of Christian Mystics enjoyed it. Wilson had a deft touch for pointing out the absurdities of America’s metaphysical religions. He started a chapter in his novel The Wrong Twin thusly:

“Archeologists of a future age will doubtless, in their minute explorations of this region, come upon the petrified remains of golf balls in such number as will occasion learned dispute. Found so profusely and yet so far from any known course, they will perhaps give rise to wholly erroneous surmises. Prefacing his paper with a reference to lost secrets once possessed by other ancients, citing without doubt that the old Egyptians knew how to temper the soft metal of copper, a certain scientist will profoundly deduce from this deposit of balls, far from the vestiges of the nearest course, that people of this remote day possessed the secret of driving a golf ball three and a half miles, and he will perhaps moralize upon the degeneracy of his own times, when the longest drive will doubtless not exceed a scant mile.” (180).

Of course, the joke could be seen at the expense of scientists, too.

It was around this time that Wilson first encountered Fort’s writings, though exactly when and how is not known—even as it is subject of firm declamations. Sam Moskowitz, the science fiction fan and critic of Forteanism, wrote,

“Booth Tarkington induced Henry [sic] Leon Wilson, famed author of the Ruggles of Red Gap (with whom he collaborated on the play The Man from Home, produced in 1907, which ran for six years), to read Fort. The result was explosive. Wilson’s subsequent novel, The Wrong Twin, found a philosophic tramp printer spouting Fort’s wildest theories at the drop of a hat throughout. Perhaps Wilson should have been suspect when he wrote Bunker Bean in 1912, a book in which the lead character buys a mummy which he claims was himself in a previous incarnation.” [Sam Moskowitz, Strange Horizons, 1976, p. 239]

But this description makes no sense chronologically. Wilson’s “The Wrong Twin” was serialized in The Saturday Evening Post for ten issues starting in November 1919. Fort’s Book of The Damned was not published until 1 December 1919. What’s more, Cowan never spouts Fort’s theories. His vision of life is purely Spencerian—although he is skeptical enough to admit there’s a catch he has not quite figured out.

“There’s life for you,” Cowan says to one of his twin sons. “Life has to live on life, humans same as dogs. Life is something that keeps tearing itself down and building itself up again; everybody killing something else and eating it. … Humans are the best killers of all,” he continued, “That’s the reason they came up from monkeys, and got civilized so they were neckties and have religion and post offices and all such.”

He rhapsodizes about the age of the universe and the vast distances between suns. These are not Fortean thoughts at all! Either Moskowitz could not tell the difference between Herbert Spencer and Charles Fort, or he never read “The Wrong Twin” at all.

Nonetheless, there is a shadow of truth in what he has to say. It is likely that Tarkington turned on Wilson to Fort’s writings. Tarkington noted (in the introduction he wrote to New Lands), “A few years ago I had one of those pleasant illnesses that permit the patient to read in bed for several days without self-reproach; and I sent down to a bookstore for whatever might be available upon criminals, crimes and criminology. Among the books brought me in response to this morbid yearning was one with the title, The Book of the Damned.” We can date this illness with some degree of accuracy, thanks to Tarkington’s correspondence with Wilson. On 8 February 1920, Tarkington wrote Wilson to say that he had suffered the flu and was forced to bed for a few days of reading. He did not mention Fort, but this is likely when he read The Book of the Damned—early February 1920. (By this point, the tenth and final part of Wilson’s ‘The Wrong Twin’ had appeared in The Saturday Evening Post.)

Unfortunately, very soon after this letter there’s a long break in the correspondence between the two men, lasting until 1923, just before Tarkington wrote the introduction to Fort’s second book—and so there is no way of saying for certain that Tarkington introduced Wilson to Fort’s writings. But there was one bit of correspondence that came through during the hiatus. In October 1920 Tarkington sent a short note to Wilson advising he was sending him “some stuff.” This package may very well have included The Book of the Damned. At any rate, even if Wilson did not read Fort this early, he was surely introduced to him by Tarkington’s introduction to New Lands—so likely sometime between October 1920 and October 1923.

By the mid-1920s, though, Wilson had other matters on his mind. His marriage fell apart, resulting in a divorce in 1927. He fled to to Portland, Oregon, for two years. His children, Leon and Charis (both dropped their parental first names) saw very little of either Harry or Helen. He returned o Carmel in 1929, while Charis spent much of her time with her grandmother and an aunt, part of the San Francisco arts community. She followed in her father’s Bohemian footsteps, experimenting sexually before meeting and coupling with the photographer Edward Weston. Leon eventually drifted to Hollywood to try to become a writer.

In November 1930, Tiffany Thayer began preparing for the publication of Fort’s third book, Lo!, by starting—at the suggestion of J. David Stern—the Fortean Society. Harry Leon Wilson was not on the original list of members. But in January, as momentum—and publicity—increased, his name became attached to the project. A letter dated 22 January from Thayer drumming attention for the Society noted that Wilson wanted to join. Whether this was at his instigation, Thayer’s, or even Booth Tarkington’s is not known. The first meeting of the Fortean Society was held four days later; Wilson wasn’t there, but Thayer announced that he had joined the Society. After reading Lo!, he wrote Thayer:

“I am today returning New Lands and am sending my copy of Lo! to an inquiring friend. Also I enclose a small contribution to the Cause.

Fort is highly exciting to me. I cannot share, as fellow host, quite all of what he somewhere speaks of as his ‘bizarre hospitalities,’ but I do greatly enjoy going to his parties.

In early infancy he seems to have been bitten by a rabid astronomer--and more venom to him.

As I go down into the vale of years I grow more and more suspicious of all certainties. Perhaps in another dozen years some one will be attacking Fort’s certainties and I’ll be for that guy, too.

A note from Milliken the other day--’99/100 of what is written on four dimensions is merely nonsense.’ It’s up to C.F. to take care of that minute reminder [sic]. With Einstein as the North Pole and Fort as the South, maybe we can get somewhere. I shall look forward to the next assault on old walls.” (The Fortean Society Magazine 8 (Dec. 1943): 12.”

The letter is interesting because it suggests that Wilson had not—or did not remember having—read New Lands, which suggests that his enthusiasm for Fort, whatever he says in the letter, was relatively subdued. It is also worth noting that Wilson yoked Fort and Einstein, a pairing that Thayer resisted for many years.

But however serious Wilson’s interest in Fort was after the founding of the Society, he soon had other, more serious matters with which to contend. In June 1932—a month after Fort died—he was in a serious car accident, which set off a series of medical problems that were to consume the next seven years until he died 28 June 1939. He had high blood pressure. He had a series of strokes. Wilson thought of writing one final work, to be called “The Stranger,” a kind of science fiction story in which an alien comes to earth and contrasts his civilization with that of earth’s, to point out the absurdities of our lives. He couldn’t pull it off, though, no longer able to concentrate well enough to write. Leon and Charis begged Tarkington for financial help—Wilson had been profligate with his fortune and ended up in debt—which Tarkington gladly supplied. Wilson’s mind turned to reflections on his literary past. He no longer though much of philosophy, telling H. L. Mencken,

“I loathe the words metaphysics and mysticism and am adding ‘philosophy’ to my proscribed list. To hell with ‘Philosophy!’ obscuring the obvious with noisy words.”

He appreciated that Twain could be great, but also that he had many weaknesses, as did H. G. Wells, telling Leon,

“And so different in his faults and failing from another man I once thought pretty big--H.G. Wells. To me now this man is pretty pathetic. A lower-middle-class Briton showing off before his social superiors. See his God-awful tripe in the June Harpers. If you can read one paragraph of it with understanding I shall ask you to return all my keepsakes and to avoid speaking when we meet. My dirty, low-down suspicion is that Wells, with his Cockney posing as one with a gift for putting the world right, is hoping for nothing less than a knighthood, than which a Briton of his class can imagine nothing more sublime. And at least old man Clemens couldn’t have been bought with anything tawdry.”

Only Ambrose Bierce continued to inspire him—and may have been a spark for “The Stranger.” He told Leon Bierce’s

“short stories are superb. I really believe no better ones were ever written. And I couldn’t name any as good. He is remarkable for his polished economy of words.”

(It is worth noting that in the same letter Wilson mentioned Bierce’s disappearances, but not Fort’s writing about that disappearance.)

If life was a card game, he was losing—but not without taking a little satisfaction. He wrote Tarkington:

“And I haven’t had a drink for a year. That slap sort of incited my blood pressure and two M.D’s, close-herding me, struck out all alcohol, after I’d been imbibing fluently for forty-five years. Funny, but I let the hard liquor go with never a yearning. I handle it, serve it, almost every day, make cocktails and such, and probably will never again want even a sip. But I do miss the wine. I’d just acquired the tail end of the wine cellar of a famous old restaurant in S.F. and I often go into the basement to stand wistful in the presence of a couple hundred quarts of authentic Burgundy, Chablis, Moselle and so on, but all I can do is give it away to people so unappreciative I know they’d rather have the current Scotch or even gin with a bar sinister. And I’m not even let to have coffee. But once a week I debauch myself with the real stuff. Drink two cups and am inebriated perfectly, as by four stiff high-balls, joyous, approachable, ready to grant any favor. So far the M.D’s haven’t found me out.”

In September, Harry Leon Wilson received a letter from Tiffany Thayer, along with a copy of the first issue of the Fortean Society Magazine. Wilson had not been involved with the legal wrangling around the ownership of Fort’s notes, so had no idea that a Society was in the works, and it seems that he wrote to Tarkington asking him what the deal was. Tarkington responded in October. His penmanship by this—never great to begin with—was horrid, and some of the words are indecipherable, but the gist is clear:

“Gold--I’d just written you & sent you a book when there came your letter. Hasten to dispense any suspicions you may have about my friendship for, or with, Mr. Tiffany T. Never see the bird. Years ago some people, no acquaintances of mine and [] this T.T. formed the “Fortean Soc.” and I signed up by mail, as understood the purpose was to be of use to that extraordinary man, Charles Fort, attract notice to his writings by giving a dinner for him, etc. (Fort was a great fellow--disappointed in me because it was a more literary than scientific interest in his works, he wrote me he’d discovered a terrific gulf in some constellation, a trillion mile vacuum, and had named it ‘Tarkington Gulf.’) I never saw [a]live; he used to live with Dreiser. Well, this summer Mrs. Fort’s lawyer (Fort’s widow’s) wrote me T.T, withheld all of Fort’s papers--said they belonged to the Fortean Soc. and wouldn’t turn ‘em in--and asked me (the lawyer did) to make a statement that the Soc. was extinct and the widow should have the papers. I did. Heard nothing more until rec’d copy of the 1st number of the mag, which brought me some letters from []. No correspondence with T.T., who seems to be using me pretty freely. He’ll blow up pretty soon, I’d think, Evidently use of the horse [‘s] daughter.”

In short, Wilson had no interest in Thayer or the Fortean Society.

The feeling was not reciprocated, though: Thayer loved Wilson’s writings. Thayer’s 1938 novel “Little Dog Lost” was his most autobiographical: about a Hollywood script writer who, longing for a life lived by one’s own wits and strength, experiences an identity crisis. He wonders if he could ever find a “good loose trade” like Dave Cowan. He cannot, but comes up with a compromise: he’ll publish a magazine. This was Merle’s solutions, and shown to be bad in “The Wrong Twin,” but John Smith—Thayer’s alter ego—thinks the project will work if he models it on Wilson’s run at “Puck”: a satirical magazine that shows how ridiculous the world has become. Thayer did this in real life with “The Fortean Society Magazine.”

And he insisted that Wilson, however lightly connected to Fort he might be, was an exemplar of Forteanism. Wilson was only twice mentioned in the Fortean Society Magazine, the first being notice of his death, and the second an encomium to him: In the December 1943 issue, Thayer published the letter that Wilson had sent him as well as a long excerpt from “The Wrong Twin” which reflected Dave Cowan’s thoughts on life. (Perhaps this is where Moskowitz got the idea that Dave Cowan was spouting Fortean theories.) Thayer added:

“Harry Leon Wilson towered over all his contemporary writers, the chiefest literary talent this country has produced since Mark Twain. Neither George Ade, nor Frank Norris, nor Sinclair Lewis could touch him; and Forteans who have not read Ma Pettengill, Merton of the Movies, Boss of Little Arcady, Bunker Bean and the Wrong Twin, quoted above, are advised to treat themselves promptly.”

It seems quite clear the Fortean Society wanted Harry Leon Wilson far more than Wilson wanted to be associated with the Society.