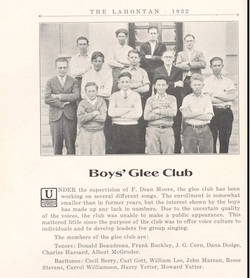

Harry G. Yetter, from his high school yearbook.

Harry G. Yetter, from his high school yearbook. A minor Fortean—a major leap.

Doubt 14 (Spring 1946) has a couple of credits to someone named Yetter. At least one clipping came from an old issue of the Oakland Tribune. Not much to go on . . . except: the May 1946 issue of Round Robin, publication of N. Meade Layne’s Borderlands Science Research Association prints part of a letter from Harry G. Yetter. And, as it happens, there are public records for someone named Harry G. Yetter living in the Oakland area from around this time. (Remarkably, Yetter is a fairly common name, and there are several Yetters living in the East Bay during the 1940s.) So, let’s make that leap: the Fortean Yetter is the same as the Round Robin Yetter.

Thus, we have Harry Garford Yetter, born 19 April 1911 in Fallon, Nevada, to Harry J. and Caroline Yetter. Harry the elder was a descendant of German immigrants via Massachusetts. He worked as a cashier. Harry the younger had four younger siblings—which accords with the letter that he wrote to Round Robin. By 1930, he had moved to Oakland, where he lived with an uncle—the uncle was a bank secretary and Harry was working with an investment house. The family was well-off, the uncle and aunt owning a home valued at $10,000. In 1937, he married Nevada Evelyn Warren, a fellow Nevada transplant to the Bay Area. Three years later, having only graduated from high school, Yetter was a broker, living with his wife’s parents in Oakland. His father-in-law was a chocolate dipper for a candy company.

Doubt 14 (Spring 1946) has a couple of credits to someone named Yetter. At least one clipping came from an old issue of the Oakland Tribune. Not much to go on . . . except: the May 1946 issue of Round Robin, publication of N. Meade Layne’s Borderlands Science Research Association prints part of a letter from Harry G. Yetter. And, as it happens, there are public records for someone named Harry G. Yetter living in the Oakland area from around this time. (Remarkably, Yetter is a fairly common name, and there are several Yetters living in the East Bay during the 1940s.) So, let’s make that leap: the Fortean Yetter is the same as the Round Robin Yetter.

Thus, we have Harry Garford Yetter, born 19 April 1911 in Fallon, Nevada, to Harry J. and Caroline Yetter. Harry the elder was a descendant of German immigrants via Massachusetts. He worked as a cashier. Harry the younger had four younger siblings—which accords with the letter that he wrote to Round Robin. By 1930, he had moved to Oakland, where he lived with an uncle—the uncle was a bank secretary and Harry was working with an investment house. The family was well-off, the uncle and aunt owning a home valued at $10,000. In 1937, he married Nevada Evelyn Warren, a fellow Nevada transplant to the Bay Area. Three years later, having only graduated from high school, Yetter was a broker, living with his wife’s parents in Oakland. His father-in-law was a chocolate dipper for a candy company.

There is no record of Yetter in the World War II registration files, which doesn’t necessarily mean anything. We do know that Yetter had four children. Nevada passed away in 1966, after almost thirty years of marriage. Sometime after, he married Edna Smith, who also passed away before him. She died in 1993. He finally died in 2002. His obituary helps to make sense of his interest in Forteanism and Round Robin, although only vaguely.

According to that obituary, he came to the East Bay in 1928; the letter to Round Robin that it was around this time—he dates it as being 17 years old—that he came in contact with the occult. He had a mentor, he said, a “Mr. R.” The obituary notes that while working at the brokerage firm, he met his lifelong friend Elwin “Rocky” R. Stone, who certainly could have been the Mr. R. in question. Right or wrong, this Mr. R. helped Yetter make sense of a childhood experience.

He said that he had an excellent memory, and could recall events that occurred before he was two years old, including the visiting of a revenant he called, for reasons unknown even to himself, Goff. He wrote in Round Robin,

“I usually was paralyzed while it was going on, whether through fright or as a part of the phenomenon, I don't know. But to see this grayish mess of misshapen Something, staring with fixed eyes, wild hair Medusa-like, and a face like Hugo's Laughing Man, was enough to frighten even a materialist. This GOFF bothered me continually until I was about 17, after that it let me alone for several years.”

This description sounds a lot like the folklore of the Old Hag, which has been shown to be an actual physiological response by the folklorist and doctor David Hufford—what is now known as sleep paralysis: “It always appeared from my left side, and just behind me as I would turn my head. I would catch a glimpse of this monstrosity, and then it would glide slowly across the room from left to right, just about head level. Its entrance was always preceded by a sharp rap on the wall (similar to a natural 'crack' due to change of temperature). And as the Goff faded through the wall opposite a final rap or crack came from that wall.” But there’s more to it than that, since Yetter’s siblings also encountered Goff.

In 1936, just before he was married, Yetter was again visited by the Goff. He was frustrated: seven years of occult training, and he could still not control these visions. Yetter’s Mr. R. told him:

"Harry, you've got to call up the Goff consciously, and hold him, and disintegrate him with a ray of light. It's your own mess, your own Karma, your own family - it's an aspect of the Dweller. It has been held away from you until you passed certain points. Now is the time for the test. Get rid of it!"

Well, R. left and I went to work on this 'thing.' I never put in such a bad time in my life. I know I sweat blood. But I did as I was told and was able to smash the figure. But I say figure only, because, as I mentioned, when I talk or write about him I can feel that same old feeling.”

Yetter wasn’t sure what the Goff was; N. Meade Layne thought it an ‘elemental,’ a being that could move between the material realm and the ethereal world.

Something dramatic seems to have happened just after 1940. Yetter and Rocky joined the freemasons—he was initiated into Bay View Lodge No. 401 on 12 April 1941. He would go on to serve as Master in the 1970s and receive awards in the 1980s. Later, he would join the Oakland Bodies Scottish Rite, and serve as its librarian from 1959 to 1973, and become a member of the Masonic Research Group of San Francisco, also serving as its president in the 1960s. Also in 1941, he became a member of the Carpenters and Joiners Local 36, which indicates a radical change in career: from broker to carpenter. He served as its president for most of the 1960s; he retired in 1974.

Yetter’s name only appears in that one issue of Doubt, both credits on the same page. One dealt with the discovery of about 5,000 registered and first class letters dumped along the Green River near Walton, Ill. Some dated back to 1922. It was a rather mundane example of government incompetence, well covered in the papers—athough the conclusion was unclear. Somehow the mail was left behind when an old post office was closed, then dumped by construction workers tearing down the building.

The other contribution was more complicated. Somehow, Yetter had come across a clipping from the Oakland Tribune dated 16 October 1920 that reported a strange rain in front of a Dublin, Georgia, bank: the rain started only a short distance above the ground on an otherwise clear day. It lasted, off and on, for three years. That same day Duncan McDougall died: he was a Massachusetts doctor who tried to weigh the human soul by biking around town, visiting people who were on the verge of dying, and weighing them with a postal scale just before and just after they passed. He is the source of the 21 grams (or 3/4 of an ounce) figure often given as the soul’s mass.

Thayer—perhaps on his own, perhaps because of something Yetter said—had McDougall dying in Oakland. That would make the coincidence of the rain a little stronger: McDougall died in Oakland, and the report of the rain appeared in an Oakland paper. As it was, McDougall died in Massachusetts. So what is meant by the coincidence is unclear.

As is, generally, the nature of Yetter’s Forteanism. He seems to have been interested in coincidences and, assuming he was the same man who wrote into Round Robin, the occult generally, including its manifestation in freemasonry.

According to that obituary, he came to the East Bay in 1928; the letter to Round Robin that it was around this time—he dates it as being 17 years old—that he came in contact with the occult. He had a mentor, he said, a “Mr. R.” The obituary notes that while working at the brokerage firm, he met his lifelong friend Elwin “Rocky” R. Stone, who certainly could have been the Mr. R. in question. Right or wrong, this Mr. R. helped Yetter make sense of a childhood experience.

He said that he had an excellent memory, and could recall events that occurred before he was two years old, including the visiting of a revenant he called, for reasons unknown even to himself, Goff. He wrote in Round Robin,

“I usually was paralyzed while it was going on, whether through fright or as a part of the phenomenon, I don't know. But to see this grayish mess of misshapen Something, staring with fixed eyes, wild hair Medusa-like, and a face like Hugo's Laughing Man, was enough to frighten even a materialist. This GOFF bothered me continually until I was about 17, after that it let me alone for several years.”

This description sounds a lot like the folklore of the Old Hag, which has been shown to be an actual physiological response by the folklorist and doctor David Hufford—what is now known as sleep paralysis: “It always appeared from my left side, and just behind me as I would turn my head. I would catch a glimpse of this monstrosity, and then it would glide slowly across the room from left to right, just about head level. Its entrance was always preceded by a sharp rap on the wall (similar to a natural 'crack' due to change of temperature). And as the Goff faded through the wall opposite a final rap or crack came from that wall.” But there’s more to it than that, since Yetter’s siblings also encountered Goff.

In 1936, just before he was married, Yetter was again visited by the Goff. He was frustrated: seven years of occult training, and he could still not control these visions. Yetter’s Mr. R. told him:

"Harry, you've got to call up the Goff consciously, and hold him, and disintegrate him with a ray of light. It's your own mess, your own Karma, your own family - it's an aspect of the Dweller. It has been held away from you until you passed certain points. Now is the time for the test. Get rid of it!"

Well, R. left and I went to work on this 'thing.' I never put in such a bad time in my life. I know I sweat blood. But I did as I was told and was able to smash the figure. But I say figure only, because, as I mentioned, when I talk or write about him I can feel that same old feeling.”

Yetter wasn’t sure what the Goff was; N. Meade Layne thought it an ‘elemental,’ a being that could move between the material realm and the ethereal world.

Something dramatic seems to have happened just after 1940. Yetter and Rocky joined the freemasons—he was initiated into Bay View Lodge No. 401 on 12 April 1941. He would go on to serve as Master in the 1970s and receive awards in the 1980s. Later, he would join the Oakland Bodies Scottish Rite, and serve as its librarian from 1959 to 1973, and become a member of the Masonic Research Group of San Francisco, also serving as its president in the 1960s. Also in 1941, he became a member of the Carpenters and Joiners Local 36, which indicates a radical change in career: from broker to carpenter. He served as its president for most of the 1960s; he retired in 1974.

Yetter’s name only appears in that one issue of Doubt, both credits on the same page. One dealt with the discovery of about 5,000 registered and first class letters dumped along the Green River near Walton, Ill. Some dated back to 1922. It was a rather mundane example of government incompetence, well covered in the papers—athough the conclusion was unclear. Somehow the mail was left behind when an old post office was closed, then dumped by construction workers tearing down the building.

The other contribution was more complicated. Somehow, Yetter had come across a clipping from the Oakland Tribune dated 16 October 1920 that reported a strange rain in front of a Dublin, Georgia, bank: the rain started only a short distance above the ground on an otherwise clear day. It lasted, off and on, for three years. That same day Duncan McDougall died: he was a Massachusetts doctor who tried to weigh the human soul by biking around town, visiting people who were on the verge of dying, and weighing them with a postal scale just before and just after they passed. He is the source of the 21 grams (or 3/4 of an ounce) figure often given as the soul’s mass.

Thayer—perhaps on his own, perhaps because of something Yetter said—had McDougall dying in Oakland. That would make the coincidence of the rain a little stronger: McDougall died in Oakland, and the report of the rain appeared in an Oakland paper. As it was, McDougall died in Massachusetts. So what is meant by the coincidence is unclear.

As is, generally, the nature of Yetter’s Forteanism. He seems to have been interested in coincidences and, assuming he was the same man who wrote into Round Robin, the occult generally, including its manifestation in freemasonry.