A Kiwi Fortean.

I have very little biographical information on Guy Powell, so little it comes close to violating my rule that I only write about Forteans whom I have researched. But there’s enough, and he’s an interesting character, so I will bend the rule a bit. (Not for the last time.) What I do know comes from some biographical blurbs tagged to articles he published in academic journals and a few brief comments in a letter that he wrote to both Tiffany Thayer and Eric Frank Russell.

Guy Powell was born 5 November 1921 (Guy Fawkes’ Day, he noted) in New Zealand, to a family that traced its roots back to Yorkshire. In the 1940s and 1950s he lived in Dunedin. This may have also been the same Guy Powell who appeared in Te Karere, the publication of New Zealand’s Mormon community, giving the report on the Dunedin Branch in 1947. During his early to mid-twenties, Powell devised a linguistic theory that rewrote Polynesian history, and circulated it among scholars. He taught at Maori schools from 1950-1952. These were the institutional descendants of missionary schools, with the aim of Europeanizing the population; there had been a change in policy during the 1940s, the goal now preservation of Maori culture, but Powell thought the change had not taken effect.

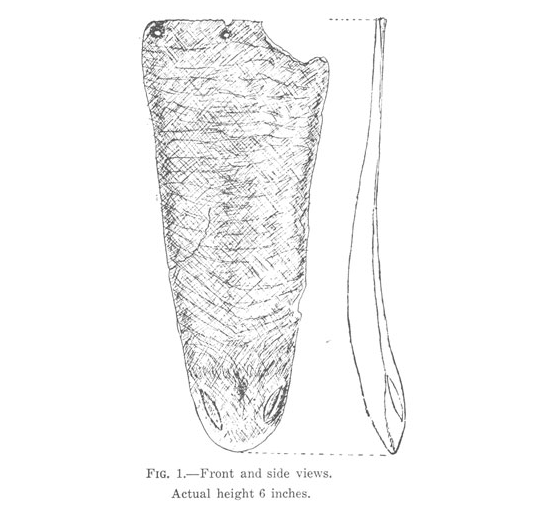

Powell was associated with the Journal of the Polynesian Society as early as March 1950. In September, he published a paper in that journal titled “Notes on a Maori Whale Ivory Pendant.” This piece was very short, only a brief description and drawing of the object, with a description of its provence. By 1953, according to the Journal of Austronesian Studies, Powell had enrolled in the Department of Anthropology at Auckland University. In March of the year, he published another article on The Journal of the Polynesian Society, this one trotting out his own theories about the linguistic development of Melanesian languages. These were ideas he’d been playing with for years, but now had time to write them up.

I have very little biographical information on Guy Powell, so little it comes close to violating my rule that I only write about Forteans whom I have researched. But there’s enough, and he’s an interesting character, so I will bend the rule a bit. (Not for the last time.) What I do know comes from some biographical blurbs tagged to articles he published in academic journals and a few brief comments in a letter that he wrote to both Tiffany Thayer and Eric Frank Russell.

Guy Powell was born 5 November 1921 (Guy Fawkes’ Day, he noted) in New Zealand, to a family that traced its roots back to Yorkshire. In the 1940s and 1950s he lived in Dunedin. This may have also been the same Guy Powell who appeared in Te Karere, the publication of New Zealand’s Mormon community, giving the report on the Dunedin Branch in 1947. During his early to mid-twenties, Powell devised a linguistic theory that rewrote Polynesian history, and circulated it among scholars. He taught at Maori schools from 1950-1952. These were the institutional descendants of missionary schools, with the aim of Europeanizing the population; there had been a change in policy during the 1940s, the goal now preservation of Maori culture, but Powell thought the change had not taken effect.

Powell was associated with the Journal of the Polynesian Society as early as March 1950. In September, he published a paper in that journal titled “Notes on a Maori Whale Ivory Pendant.” This piece was very short, only a brief description and drawing of the object, with a description of its provence. By 1953, according to the Journal of Austronesian Studies, Powell had enrolled in the Department of Anthropology at Auckland University. In March of the year, he published another article on The Journal of the Polynesian Society, this one trotting out his own theories about the linguistic development of Melanesian languages. These were ideas he’d been playing with for years, but now had time to write them up.

Based on his reading, Melanesian (and the related Polynesian) languages included a large number of loan words from Indonesian languages—words of great and intimate import—which suggested the need to rewrite the accepted history of the Pacific in order to posit a close relationship between Indonesian and Melanesian people. He thought that Indonesian people colonized the uninhabited islands of Melanesia and settled down, slowly diverging into a new, Polynesian culture. Later, a wave oaf “dark-skinned, fuzzy-haired people, speaking a Papuan language,” likely from New Guinea, overwhelmed the first colonizers. Because dark skin and fuzzy hair are genetically “dominant” (?), this physiognomy prevails. The Papuan language became dominant, chasing out all but the most intimate original words—and thus explaining the findings that Powell summarized.

Powell ended his essay acknowledging it was revolutionary and more exploratory than definitive. He also admitted he had no academic training in linguistics—unavailable in New Zealand at the time—and had only limited access to books on the Pacific languages. He hoped his enthusiasm would make up for some of these deficiencies, but was also open to criticism. Which he received. the following year, Dr. A Capell and Stefan Wurm separately disputed Powell’s conclusions, pointing out a number of facts which he had overlooked. Powell offered a rebuttal, but it took up only a few of those objections and insisted that other experts had vetted his ideas. The response suggested that he was not quite as open to criticism as his paper suggested. More, though, the general lack of response suggested how far out of the mainstream Powell was: his ideas need not even be engaged.

In late 1955, he published another piece, this one on his experiences teaching at Maori schools. His ideal for the schools was that a new, syncretic culture might emerge if the Maori were allowed to integrate the best of their cultural heritage with that of the European. That just wasn’t happening. Indeed, it was common that the younger generation was not learning Maori language at all—never mind the official changes that had occurred back in the 1940s. As a result, Maori culture was declining, and would continue to decline without teachers specially trained in the language and culture. According to John Barrington’s Separate but Equal?: Maori Schools and the Crown 1867-1969, Powell’s article caused something of a controversy among school leaders. Judith A. Simon, Linda Tuhiwai Smith make a similar point, in their earlier A Civilising Mission?: Perceptions and Representations of the Native Schools System. The result seems to have been the same as his linguistic theorizing: a brief protest by authorities, followed by Fortean damning of his conclusions.

I do not know if Powell ever finished his studies. He was still at the Department of Anthropology in 1955, but that is the last I can find. But he seems to have continued his interest in Maori culture. In the 1960s, he helped James W. Ritchie in his work on Maori folklore “The Making of a Maori” and also received acknowledgments for aiding with “The Reed Book of Māori Mythology.”

In 1958, his address was in Wellington, and he was associated with “Truth.” This may have been a tabloid newspaper.

I do not know when he died. Indeed, he may still be alive. He’d be in his 90s now.

**********

Powell described his coming to Fort, Forteanism, and the Fortean Society in his 1958 letter. He wrote, “I borrowed ‘THE BOOKS’ from local free library in 1946 at a time when my intellect must have been just ripe for such stimulus. Stirred, staggered, stimulated, stampeded, star-lit, startled, stung, straightened, strengthened, struck studious, stumped—how can one describe the chaotic yet freshly-awakened state of the intellect on which Fort has newly burst?—I immediately communicated with he Society in new York; granted membership (first such in new Zealand) have, despite impecuniousness which has prevented my contributing financially to the funds—this earning occasional, justified criticisms from T.T.—, remained a Member of the Fortean Society (and the accredited Centre for New Zealand as listed in the masthead of later “Doubts”) for 11 years—up to the present time, I have at all times tried to justify my non-financial-member status by collecting and forwarding to New York H.Q. all the Forteanwise interesting data I came across; also by acting as a Fortean in participating in newspaper correspondences, in original free-lance journalistic contributions, and in orientating my scientific training and research (in Pacific social anthropology and linguistics); and doing all I could in personal discussions and writings to recruit likely individuals to the Fortean position and membership, through acquaintance with “THE BOOKS”, “Doubt”, or other Fortean publications.”

Between 1947 and 1958, Powell appeared in Doubt five times. The mentions in Doubt, though, are not guaranteed to be the same person due to Thayer’s idiosyncratic notation system. The first time the name appeared was in Doubt 19 (October 1947) as part of a long paragraph of credits for people who had sent in material on flying saucers. It is worth noting that the name is spelled differently, with only one L: Powel. That may or may not have been a typographical error. The second mention is also confuasing. Doubt 21, from June 1948, refers to an “A. E. Powell,” who—along with a number of other members—contributed a story about a rain the color of “lime soda pop” in Dayton, Ohio. Probably that’s some one different, but, if so, it is the only mention of a Powell with those initials in the run of Doubt.

Only with references beginning in 1953 are we on firmer ground. Issue 39 (January 1953) had three mentions, both of whom refer to the Kiwi Guy Powell. On page 180, in Thayer’s run down of the best contributions for the quarter, he notes that “Powell from New Zealand” sent in two articles from the Dunedin Evening Star. The first, a wire story, is a version of an urban legend that continues to circulate: a hostess fed her guests canned salmon, then left the can n the porch for her cat; later she found the cat dead. All the guests were given ptomaine and had their stomach pumps. Some time afterward, a neighbor told the woman her cat had been hit b a car and he had set it on the porch for her, but didn’t ring because he didn’t want to ruin the party. The second was a report on H. H. Nininger, who directed the American Meteorite Museum in Arizona. He found a glass tunnel on the moon, several miles long, and was studying to see if it would be a good shelter for future explorers. Thayer quipped, “Let us know, Doc!” A page later, “G. Powell” was included among the long list of people who had contributed flying saucer material—which does give some credence to his being the one mentioned in 1947.

Around the end of 1956 or beginning of 1957, Powell must have written Thayer to say that he was prepared to pay his dues. In January 1957, Thayer alerted Russell to the development and asked to be told when the payment went through, so that he could then pass on back issues to Powell. Because of the difficulties of converting money, Russell handled almost all worldwide membership, but especially those within the British empire. Judging by the comments Powell made the following year, the check never cashed. But the letter brought him renewed attention by the Society.

Powell again was among the contributors of Thayer’s favorite items the next month, in Doubt 53 (February 1957). Powell’s piece again came from the Dunedin Evening Star and supplemented a report from E M G Hibbert of Tasmania, about a bull that was slaughtered, its skull opened, and . . . something found. The report was confused, alternately saying it was a rat—on the word of two experienced slaughterman—unidentified and needing further study at the department of agriculture, and an embryo (though Thayer noted, presumably as a form of skepticism, there was no umbilical cord or placenta.) It is, of course, impossible to say at this late date, but the presence of undeveloped embryos attached to the brain of mammals is a rare phenomenon but not unknown. The condition goes by various names, a technical one being Craniopagus parasiticus.

It was on 1 April 1958—a very Fortean day—that Powell typed up his letter to Russell and Thayer. He included the biographical paragraph to bring Russell up to speed—in the eleven years, he’d only communicated with Thayer. But he’d been thinking about the Fortean Society during all that time, and now had big plans for its antipodal spread. He wrote, “Now I am convinced that the time is ripe for an attempt to get ‘Doubt’ out to a wider readership in New Zealand (at present restricted to a tiny membership, and ten libraries, several of which to my knowledge do not make it available to readers but discard it upon receipt!) by putting it in the hands of one of the Dominion’s large-scale agencies that make a business of handling, distributing, advertising, and generally retailing overseas publications. Granted sole distribution rights for New Zealand (or even for the whole area of Australasia—N.Z., Australia, New Guinea and adjacent islands and territories) for ‘Doubt’, and for the other publications which the Fortean Society makes available, I feel confident that one of the local firms could be interested in distributing Fortean Society material, so long as I could be allowed a free hand to assure them of a reasonable profit-margin; regularity of supplies; no dollar expenditure, but all dealing with soft-currency area (through E.F.R.)

“I have already addressed a preliminary later to two of N.Z.’s leading distributing forms electing ones which already have sole agencies in N.Z. (or A’Asia) for science fiction/fantasy publications (one for Nova Publications’ ‘New Worlds S-F’ & “Science Fantasy”; the other, a bigger firm, distributes Perth’s Munro Press’s ‘Nebula-S-F’ etc., ‘Galaxy’, etc., in NZ and Australia plus a wide rate of other publications. In order to create the requisite commercial atmosphere, I described myself in my letters (not without some justification) as ‘sole representative for the Fortean Society of New Zealand.’ Further, I promised soon to be in a position to inform them of prices for ‘Doubts’, wholesale, landed in NZ, (a) ex-ship; (b) ex-plane, for parcels containing 100, 250, 500 and 1000 copies; advice as to future publication dates, and intervals; and undertook soon tone able to sup[ply specimen copies of past issues of ‘Doubt” (I suggest three recent back copies in duplicate—one set for each firm). I gave ‘Doubt’ as excellent a build-up—blurb—as possible.

“Please co-operate urgently by airmailing the information needed to supply the promised details; and the specimen copies. Let me know by earliest airmail (both T.T. and E.F.R.) your reactions to this scheme of mine, especially any factors known to you which might invalidate my offers to the agencies. While I cannot give any firm undertaking as to certainty of retail sales here in NZ, I can promise that I will do all in my power to further such sales (this side of illegality!) so long as I am assured of your present and continuing co-operation and moral support.

“My erstwhile eleemosynary financial position (amounting to a permanent deficit over the last decade and a-half) has slightly improved and I can now undertake to forward to Russell by my next letter (nothing can be enclosed in this aerogram), an amount of money as an ‘act of (good) faith’! Prompt airmailed replies will be appreciated.

“With fraternal greetings, M.F.S. Guy Powell.”

In the materials that I have seen, there is no further discussion of this program, but it is doubtful anything came of it. By this point, Russell had lost a lot of enthusiasm for the Society. Thayer would have been reluctant to divulge his schedule or have to work according to conventional commercial lines—indeed, this scheme would seem to have given way too much leverage to the distributors. Besides, there was no chance the distributors would make money selling Doubt (Thayer’s bookselling friends complained they never did) and the circulation numbers Powell suggest seem overly optimistic. I do not know how many copies of Doubt went out, but membership was likely around 3,000, with additional copies going to libraries (where they were often thrown away). And that was worldwide. Selling 100 copies of “Doubt” every quarter in New Zealand would have seemed to Thayer extremely unlikely. In fact, Powell’s enthusiasm strong suggests he had not seen recent issues of “Doubt” at all and oversold their appeal.

Whatever came of the plan—and whether Powell ever actually paid his dues—he was in the next issue of Doubt, 57, from July 1958. Actually, the name “Powell” appeared twice, but only one of those mentions is definitely the New Zealander. (The other one may or may not be.) A list of people who had contributed material on flying saucers included a reference to “Powell.” The other citation left no ambiguity. In a long column on weird falls, Thayer credited a Powell who had contributed material from the “Dunedin Evening Star.” This article told of a series of strange rock falls in Pumphrey, Australia, over the course of three evenings, and then an entire day. The report appeared on 19 March 1957. What Thayer did not mention about the story was that it was a cause of dispute among different groups of Australian aboriginals.

That detail may seem insignificant, but it points to a broader issue in understanding Powell’s relationship to Forteanism. Powell would seem to have certain interests that fit with the Fortean Society. Thayer was an advocate of aboriginal rights in America, championing the “Indian” cause. The Fortean Society also hosted bits on linguistic heterodoxy—such as American Indians speaking some northern European languages, and other ideas promulgated by German Forteans—theories that contradicted accepted historical narratives. Powell could seemingly have nestled his ideas in with these Fortean themes. But if he did, Thayer did not report it. Maybe that was because he wasn’t ever reading any issues of “Doubt,” or only irregularly, given his failure to pony up dues and the difficulty of sending the magazine to New Zealand. (In other cases, Thayer was happy to float members years of dues.)

Either way, what is striking is that his contributions to the Fortean Society do not seem to have related to his own research. (Although one is not sure what he may have said with the contribution of the last story on falls.) Rather, his more certain contributions display an interest in flying saucers or at least odd aerial phenomena. (Again, Thayer’s editorial judgment makes it impossible to tell what point Powell was trying to communicate.) He also contributed more typical Fortean anomalies—the animal in the bull’s head (which was probably explicable) and strange rains of objects. The story about the glass tunnel burrowed into the surface of the moon by a meteorite may suggest that Powell was as skeptical as Thayer (and Fort!) of astronomers—and, in this case, rightly so. (Nininger was otherwise a respected amateur, and was also involved in investigating the weird explosion over Kansas in February 1948 that so intrigued Fortean Norman Markham.) The story of the cat and the canned salmon also suggests a sense of Fortean humor, one that was not too concerned over such niceties as “did it really happen.”

What really comes clear from all of this material is that Powell was only distantly connected to the Society, even if his name appeared on the masthead. He may not have even been reading the magazines. Rather, he had been intrigued by Fort, tried to follow up, but the exigencies of a life on the fringe—both culturally and ecologically—left him untethered. So that when he did finally try to make a splash and spread the Fortean word, his ideas were completely pie-in-the-sky.

Powell ended his essay acknowledging it was revolutionary and more exploratory than definitive. He also admitted he had no academic training in linguistics—unavailable in New Zealand at the time—and had only limited access to books on the Pacific languages. He hoped his enthusiasm would make up for some of these deficiencies, but was also open to criticism. Which he received. the following year, Dr. A Capell and Stefan Wurm separately disputed Powell’s conclusions, pointing out a number of facts which he had overlooked. Powell offered a rebuttal, but it took up only a few of those objections and insisted that other experts had vetted his ideas. The response suggested that he was not quite as open to criticism as his paper suggested. More, though, the general lack of response suggested how far out of the mainstream Powell was: his ideas need not even be engaged.

In late 1955, he published another piece, this one on his experiences teaching at Maori schools. His ideal for the schools was that a new, syncretic culture might emerge if the Maori were allowed to integrate the best of their cultural heritage with that of the European. That just wasn’t happening. Indeed, it was common that the younger generation was not learning Maori language at all—never mind the official changes that had occurred back in the 1940s. As a result, Maori culture was declining, and would continue to decline without teachers specially trained in the language and culture. According to John Barrington’s Separate but Equal?: Maori Schools and the Crown 1867-1969, Powell’s article caused something of a controversy among school leaders. Judith A. Simon, Linda Tuhiwai Smith make a similar point, in their earlier A Civilising Mission?: Perceptions and Representations of the Native Schools System. The result seems to have been the same as his linguistic theorizing: a brief protest by authorities, followed by Fortean damning of his conclusions.

I do not know if Powell ever finished his studies. He was still at the Department of Anthropology in 1955, but that is the last I can find. But he seems to have continued his interest in Maori culture. In the 1960s, he helped James W. Ritchie in his work on Maori folklore “The Making of a Maori” and also received acknowledgments for aiding with “The Reed Book of Māori Mythology.”

In 1958, his address was in Wellington, and he was associated with “Truth.” This may have been a tabloid newspaper.

I do not know when he died. Indeed, he may still be alive. He’d be in his 90s now.

**********

Powell described his coming to Fort, Forteanism, and the Fortean Society in his 1958 letter. He wrote, “I borrowed ‘THE BOOKS’ from local free library in 1946 at a time when my intellect must have been just ripe for such stimulus. Stirred, staggered, stimulated, stampeded, star-lit, startled, stung, straightened, strengthened, struck studious, stumped—how can one describe the chaotic yet freshly-awakened state of the intellect on which Fort has newly burst?—I immediately communicated with he Society in new York; granted membership (first such in new Zealand) have, despite impecuniousness which has prevented my contributing financially to the funds—this earning occasional, justified criticisms from T.T.—, remained a Member of the Fortean Society (and the accredited Centre for New Zealand as listed in the masthead of later “Doubts”) for 11 years—up to the present time, I have at all times tried to justify my non-financial-member status by collecting and forwarding to New York H.Q. all the Forteanwise interesting data I came across; also by acting as a Fortean in participating in newspaper correspondences, in original free-lance journalistic contributions, and in orientating my scientific training and research (in Pacific social anthropology and linguistics); and doing all I could in personal discussions and writings to recruit likely individuals to the Fortean position and membership, through acquaintance with “THE BOOKS”, “Doubt”, or other Fortean publications.”

Between 1947 and 1958, Powell appeared in Doubt five times. The mentions in Doubt, though, are not guaranteed to be the same person due to Thayer’s idiosyncratic notation system. The first time the name appeared was in Doubt 19 (October 1947) as part of a long paragraph of credits for people who had sent in material on flying saucers. It is worth noting that the name is spelled differently, with only one L: Powel. That may or may not have been a typographical error. The second mention is also confuasing. Doubt 21, from June 1948, refers to an “A. E. Powell,” who—along with a number of other members—contributed a story about a rain the color of “lime soda pop” in Dayton, Ohio. Probably that’s some one different, but, if so, it is the only mention of a Powell with those initials in the run of Doubt.

Only with references beginning in 1953 are we on firmer ground. Issue 39 (January 1953) had three mentions, both of whom refer to the Kiwi Guy Powell. On page 180, in Thayer’s run down of the best contributions for the quarter, he notes that “Powell from New Zealand” sent in two articles from the Dunedin Evening Star. The first, a wire story, is a version of an urban legend that continues to circulate: a hostess fed her guests canned salmon, then left the can n the porch for her cat; later she found the cat dead. All the guests were given ptomaine and had their stomach pumps. Some time afterward, a neighbor told the woman her cat had been hit b a car and he had set it on the porch for her, but didn’t ring because he didn’t want to ruin the party. The second was a report on H. H. Nininger, who directed the American Meteorite Museum in Arizona. He found a glass tunnel on the moon, several miles long, and was studying to see if it would be a good shelter for future explorers. Thayer quipped, “Let us know, Doc!” A page later, “G. Powell” was included among the long list of people who had contributed flying saucer material—which does give some credence to his being the one mentioned in 1947.

Around the end of 1956 or beginning of 1957, Powell must have written Thayer to say that he was prepared to pay his dues. In January 1957, Thayer alerted Russell to the development and asked to be told when the payment went through, so that he could then pass on back issues to Powell. Because of the difficulties of converting money, Russell handled almost all worldwide membership, but especially those within the British empire. Judging by the comments Powell made the following year, the check never cashed. But the letter brought him renewed attention by the Society.

Powell again was among the contributors of Thayer’s favorite items the next month, in Doubt 53 (February 1957). Powell’s piece again came from the Dunedin Evening Star and supplemented a report from E M G Hibbert of Tasmania, about a bull that was slaughtered, its skull opened, and . . . something found. The report was confused, alternately saying it was a rat—on the word of two experienced slaughterman—unidentified and needing further study at the department of agriculture, and an embryo (though Thayer noted, presumably as a form of skepticism, there was no umbilical cord or placenta.) It is, of course, impossible to say at this late date, but the presence of undeveloped embryos attached to the brain of mammals is a rare phenomenon but not unknown. The condition goes by various names, a technical one being Craniopagus parasiticus.

It was on 1 April 1958—a very Fortean day—that Powell typed up his letter to Russell and Thayer. He included the biographical paragraph to bring Russell up to speed—in the eleven years, he’d only communicated with Thayer. But he’d been thinking about the Fortean Society during all that time, and now had big plans for its antipodal spread. He wrote, “Now I am convinced that the time is ripe for an attempt to get ‘Doubt’ out to a wider readership in New Zealand (at present restricted to a tiny membership, and ten libraries, several of which to my knowledge do not make it available to readers but discard it upon receipt!) by putting it in the hands of one of the Dominion’s large-scale agencies that make a business of handling, distributing, advertising, and generally retailing overseas publications. Granted sole distribution rights for New Zealand (or even for the whole area of Australasia—N.Z., Australia, New Guinea and adjacent islands and territories) for ‘Doubt’, and for the other publications which the Fortean Society makes available, I feel confident that one of the local firms could be interested in distributing Fortean Society material, so long as I could be allowed a free hand to assure them of a reasonable profit-margin; regularity of supplies; no dollar expenditure, but all dealing with soft-currency area (through E.F.R.)

“I have already addressed a preliminary later to two of N.Z.’s leading distributing forms electing ones which already have sole agencies in N.Z. (or A’Asia) for science fiction/fantasy publications (one for Nova Publications’ ‘New Worlds S-F’ & “Science Fantasy”; the other, a bigger firm, distributes Perth’s Munro Press’s ‘Nebula-S-F’ etc., ‘Galaxy’, etc., in NZ and Australia plus a wide rate of other publications. In order to create the requisite commercial atmosphere, I described myself in my letters (not without some justification) as ‘sole representative for the Fortean Society of New Zealand.’ Further, I promised soon to be in a position to inform them of prices for ‘Doubts’, wholesale, landed in NZ, (a) ex-ship; (b) ex-plane, for parcels containing 100, 250, 500 and 1000 copies; advice as to future publication dates, and intervals; and undertook soon tone able to sup[ply specimen copies of past issues of ‘Doubt” (I suggest three recent back copies in duplicate—one set for each firm). I gave ‘Doubt’ as excellent a build-up—blurb—as possible.

“Please co-operate urgently by airmailing the information needed to supply the promised details; and the specimen copies. Let me know by earliest airmail (both T.T. and E.F.R.) your reactions to this scheme of mine, especially any factors known to you which might invalidate my offers to the agencies. While I cannot give any firm undertaking as to certainty of retail sales here in NZ, I can promise that I will do all in my power to further such sales (this side of illegality!) so long as I am assured of your present and continuing co-operation and moral support.

“My erstwhile eleemosynary financial position (amounting to a permanent deficit over the last decade and a-half) has slightly improved and I can now undertake to forward to Russell by my next letter (nothing can be enclosed in this aerogram), an amount of money as an ‘act of (good) faith’! Prompt airmailed replies will be appreciated.

“With fraternal greetings, M.F.S. Guy Powell.”

In the materials that I have seen, there is no further discussion of this program, but it is doubtful anything came of it. By this point, Russell had lost a lot of enthusiasm for the Society. Thayer would have been reluctant to divulge his schedule or have to work according to conventional commercial lines—indeed, this scheme would seem to have given way too much leverage to the distributors. Besides, there was no chance the distributors would make money selling Doubt (Thayer’s bookselling friends complained they never did) and the circulation numbers Powell suggest seem overly optimistic. I do not know how many copies of Doubt went out, but membership was likely around 3,000, with additional copies going to libraries (where they were often thrown away). And that was worldwide. Selling 100 copies of “Doubt” every quarter in New Zealand would have seemed to Thayer extremely unlikely. In fact, Powell’s enthusiasm strong suggests he had not seen recent issues of “Doubt” at all and oversold their appeal.

Whatever came of the plan—and whether Powell ever actually paid his dues—he was in the next issue of Doubt, 57, from July 1958. Actually, the name “Powell” appeared twice, but only one of those mentions is definitely the New Zealander. (The other one may or may not be.) A list of people who had contributed material on flying saucers included a reference to “Powell.” The other citation left no ambiguity. In a long column on weird falls, Thayer credited a Powell who had contributed material from the “Dunedin Evening Star.” This article told of a series of strange rock falls in Pumphrey, Australia, over the course of three evenings, and then an entire day. The report appeared on 19 March 1957. What Thayer did not mention about the story was that it was a cause of dispute among different groups of Australian aboriginals.

That detail may seem insignificant, but it points to a broader issue in understanding Powell’s relationship to Forteanism. Powell would seem to have certain interests that fit with the Fortean Society. Thayer was an advocate of aboriginal rights in America, championing the “Indian” cause. The Fortean Society also hosted bits on linguistic heterodoxy—such as American Indians speaking some northern European languages, and other ideas promulgated by German Forteans—theories that contradicted accepted historical narratives. Powell could seemingly have nestled his ideas in with these Fortean themes. But if he did, Thayer did not report it. Maybe that was because he wasn’t ever reading any issues of “Doubt,” or only irregularly, given his failure to pony up dues and the difficulty of sending the magazine to New Zealand. (In other cases, Thayer was happy to float members years of dues.)

Either way, what is striking is that his contributions to the Fortean Society do not seem to have related to his own research. (Although one is not sure what he may have said with the contribution of the last story on falls.) Rather, his more certain contributions display an interest in flying saucers or at least odd aerial phenomena. (Again, Thayer’s editorial judgment makes it impossible to tell what point Powell was trying to communicate.) He also contributed more typical Fortean anomalies—the animal in the bull’s head (which was probably explicable) and strange rains of objects. The story about the glass tunnel burrowed into the surface of the moon by a meteorite may suggest that Powell was as skeptical as Thayer (and Fort!) of astronomers—and, in this case, rightly so. (Nininger was otherwise a respected amateur, and was also involved in investigating the weird explosion over Kansas in February 1948 that so intrigued Fortean Norman Markham.) The story of the cat and the canned salmon also suggests a sense of Fortean humor, one that was not too concerned over such niceties as “did it really happen.”

What really comes clear from all of this material is that Powell was only distantly connected to the Society, even if his name appeared on the masthead. He may not have even been reading the magazines. Rather, he had been intrigued by Fort, tried to follow up, but the exigencies of a life on the fringe—both culturally and ecologically—left him untethered. So that when he did finally try to make a splash and spread the Fortean word, his ideas were completely pie-in-the-sky.