Speculatin’ about a Kiwi Fortean.

Between 1947 and 1958, Doubt carried the name of a Fortean Society Member known as G. Powell. He was from New Zealand, Dunedin to be exact. A letter from Thayer to Eric Frank Russell makes clear his first name. Because of the difficulties of converting money, Russell handled almost all worldwide membership, but especially those within the British empire. Thayer wrote, in January 1957, that Guy Powell was paying his dues and needed to know when he check cashed so he could send him back issues.

That’s not a lot of information to go on, but it may be enough, as searches of Guy Powell in Dunedin, New Zealand uncovered the likely Fortean. In the mid-1950s, The Journal of the Polynesian Society briefly reported on and published papers by a Guy Powell, born in Dunedin, who seems to have been an autodidact in the mold of many Forteans, with the unusual theories of the autochthonous intellect. This may have also been the same Guy Powell who appeared in Te Karere, the publication of New Zealand’s Mormon community, giving the report on the Dunedin Branch in 1947. We do know from the brief biographies given in the academic journals that he was born there, in Dunedin.

Powell was associated with the Journal of the Polynesian Society as early as March 1950. In September, he published a paper in that journal titled “Notes on a Maoria Whale Ivory Pendant.” This piece was very short, only a brief description and drawing of the object, with a description of its provence. At the time, he was also teaching at Maoria schools, from 1950 to 1952. These were the institutional descendants of missionary schools, with the aim of Europeanizing the population; there had been a change in policy during the 1940s, the goal now preservation of Maori culture, but Powell thought the change had not taken effect.

Between 1947 and 1958, Doubt carried the name of a Fortean Society Member known as G. Powell. He was from New Zealand, Dunedin to be exact. A letter from Thayer to Eric Frank Russell makes clear his first name. Because of the difficulties of converting money, Russell handled almost all worldwide membership, but especially those within the British empire. Thayer wrote, in January 1957, that Guy Powell was paying his dues and needed to know when he check cashed so he could send him back issues.

That’s not a lot of information to go on, but it may be enough, as searches of Guy Powell in Dunedin, New Zealand uncovered the likely Fortean. In the mid-1950s, The Journal of the Polynesian Society briefly reported on and published papers by a Guy Powell, born in Dunedin, who seems to have been an autodidact in the mold of many Forteans, with the unusual theories of the autochthonous intellect. This may have also been the same Guy Powell who appeared in Te Karere, the publication of New Zealand’s Mormon community, giving the report on the Dunedin Branch in 1947. We do know from the brief biographies given in the academic journals that he was born there, in Dunedin.

Powell was associated with the Journal of the Polynesian Society as early as March 1950. In September, he published a paper in that journal titled “Notes on a Maoria Whale Ivory Pendant.” This piece was very short, only a brief description and drawing of the object, with a description of its provence. At the time, he was also teaching at Maoria schools, from 1950 to 1952. These were the institutional descendants of missionary schools, with the aim of Europeanizing the population; there had been a change in policy during the 1940s, the goal now preservation of Maori culture, but Powell thought the change had not taken effect.

By 1953, according to the Journal of Austronesian Studies, Powell had enrolled in the Department of Anthropology at Auckland University. In March of the year, he published another article on The Journal of the Polynesian Society, this one trotting out his own theories about the linguistic development of Melanesian languages. He had originally devised it in the mid-1940s, and circulated his ideas among some scholars, without any major criticism. Now he had time to write up what he had been thinking about more formally.

Based on his reading, Melanesian (and the related Polynesian) languages included a large number of loan words from Indonesian languages—words of great and intimate import—which suggested the need to rewrite the accepted history of the Pacific in order to posit a close relationship between Indonesian and Melanesian people. He thought that Indonesian people colonized the uninhabited islands of Melanesia and settled down, slowly diverging into a new, Polynesian culture. Later, a wave oaf “dark-skinned, fuzzy-haired people, speaking a Papuan language,” likely from New Guinea, overwhelmed the first colonizers. Because dark skin and fuzzy hair are genetically “dominant” (?), this physiognomy prevails. The Papuan language became dominant, chasing out all but the most intimate original words—and thus explaining the findings that Powell summarized.

Powell ended his essay acknowledging it was revolutionary and more exploratory than definitive. He also admitted he had no academic training in linguistics—unavailable in New Zealand at the time—and had only limited access to books on the Pacific languages. He hoped his enthusiasm would make up for some of these deficiencies, but was also open to criticism. Which he received. the following year, Dr. A Capell and Stefan Wurm separately disputed Powell’s conclusions, pointing out a number of facts which he had overlooked. Powell offered a rebuttal, but it took up only a few of those objections and insisted that other experts had vetted his ideas. The response suggested that he was not quite as open to criticism as his paper suggested. More, though, the general lack of response suggested how far out of the mainstream Powell was: his ideas need not even be engaged.

In late 1955, he published another piece, this one on his experiences teaching at Maori schools. His ideal for the schools was that a new, syncretic culture might emerge if the Maori were allowed to integrate the best of their cultural heritage with that of the European. That just wasn’t happening. Indeed, it was common that the younger generation was not learning Maori language at all—never mind the official changes that had occurred back in the 1940s. As a result, Maoria culture was declining, and would continue to decline without teachers specially trained in the language and culture. According to John Barrington’s Separate but Equal?: Maori Schools and the Crown 1867-1969, Powell’s article caused something of a controversy among school leaders. Judith A. Simon, Linda Tuhiwai Smith make a similar point, in their earlier A Civilising Mission?: Perceptions and Representations of the Native Schools System. The result seems to have been the same as his linguistic theorizing: a brief protest by authorities, followed by Fortean damning of his conclusions.

I do not know if Powell ever finished his studies. He was still at the Department of Anthropology in 1955, but that is the last I can find. But he seems to have continued his interest in Maori culture. In the 1960s, he helped James W. Ritchie in his work on Maori folklore “The Making of a Maori” and also received acknowledgments for aiding with “The Reed Book of Māori Mythology.”

I do not know when Powell was born or when he died.

*******

Nor do I know how Powell became associated with Fort, Forteanism, or the Fortean Society. His name appeared in five issues of Doubt, as well as the one letter from Thayer to Eric Frank Russell. These connections put him as part of the Society from 1947 to 1958, which covers his time teaching as well as most if not all of his time studying anthropology. The mentions in Doubt, though, are not guaranteed to be the same person due to Thayer’s idiosyncratic notation system.

The first time the name appeared was in Doubt 19 (October 1947) as part of a long paragraph of credits for people who had sent in material on flying saucers. It is worth noting that the name is spelled differently, with only one L: Powel. That may or may not have been a typographical error. The second mention also heaps speculation onto this whole speculative enterprise. Doubt 21, from June 1948, refers to an “A. E. Powell,” who—along with a number of other members—contributed a story about a rain the color of “lime soda pop” in Dayton, Ohio. Probably that’s some one different, but, if so, it is the only mention of a Powell with those initials in the run of Doubt.

Only with references beginning in 1953 are we on firmer ground. Issue 39 (January 1953) had three mentions, both of whom refer to the Kiwi Guy Powell. On page 180, in Thayer’s run down of the best contributions for the quarter, he notes that “Powell from New Zealand” sent in two articles from the Dunedin Evening Star. The first, a wire story, is a version of an urban legend that continues to circulate: a hostess fed her guests canned salmon, then left the can n the porch for her cat; later she found the cat dead. All the guests were given ptomaine and had their stomach pumps. Some time afterward, a neighbor told the woman her cat had been hit b a car and he had set it on the porch for her, but didn’t ring because he didn’t want to ruin the party. The second was a report on H. H. Nininger, who directed the American Meteorite Museum in Arizona. He found a glass tunnel on the moon, several miles long, and was studying to see if it would be a good shelter for future explorers. Thayer quipped, “Let us know, Doc!” A page later, “G. Powell” was included among the long list of people who had contributed flying saucer material—which does give some credence to his being the one mentioned in 1947.

Powell again was among the contributors of Thayer’s favorite items four years later, when he next appeared, in Doubt 53 (February 1957). (The absence implies that he wasn’t a strongly committed member.) Powell’s piece again came from the Dunedin Evening Star and supplemented a report from E M G Hibbert of Tasmania, about a bull that was slaughtered, its skull opened, and . . . something found. The report was confused alternately saying it was a rat—on the word of two experienced slaughterman—unidentified and needing further study at the department of agriculture, and an embryo (though Thayer noted, presumably as a form of skepticism, there was no umbilical cord or placenta.) It is, of course, impossible to say at this late date, but the presence of undeveloped embryos attached to the brain of mammals is a rare phenomenon but not unknown. The condition goes by various names, a technical one being Craniopagus parasiticus.

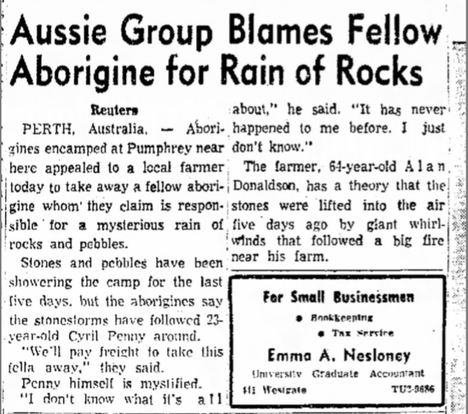

A bit more than a year later, in Doubt 57 from July 1958, Powell’s name appeared twice more, though one of those mentions was not definitely him. That was a mention in a list of people who had contributed material on flying saucers and referred only to “Powell.” The other was Guy Powell. In a long column on weird falls, Thayer credited a Powell, who had contributed material from the Dunedin Evening Star. This article told of a series of strange rock falls in Pumphrey, Australia, over the course of three evenings, and then an entire day. The report appeared on 19 March 1957. What Thayer did not mention about the story was that it was a cause of dispute among different groups of Australian aboriginals.

That detail may seem insignificant, but it points to a broader issue in understanding Powell’s relationship to Forteanism. Assuming that I have the right Guy—sorry for the pun—he would seem to have certain interests that fit with the Fortean Society. Thayer was an advocate of aboriginal rights in America, championing the “Indian” cause. The Fortean Society also hosted bits on linguistic heterodoxy—such as American Indians speaking some northern European languages, and other ideas promulgated by German Forteans—theories that contradicted accepted historical narratives. Powell could seemingly have nestled his ideas in with these Fortean themes. But if he did, Thayer did not report it. Maybe it was just what drew him to the Society, and then he found other subjects worth pursuing.

Either way, what is striking is that his contributions to the Fortean Society do not seem to have related to his own research. (Although one is not sure what he may have said with the contribution of the last story on falls.) Rather, his more certain contributions display an interest in flying saucers or at least odd aerial phenomena. (Again, Thayer’s editorial judgment makes it impossible to tell what point Powell was trying to communicate.) He also contributed more typical Fortean anomalies—the animal in the bull’s head (which was probably explicable) and strange rains of objects. The story about the glass tunnel burrowed into the surface of the moon by a meteorite may suggest that Powell was as skeptical as Thayer (and Fort!) of astronomers—and, in this case, rightly so. (Nininger was otherwise a respected amateur, and was also involved in investigating the weird explosion over Kansas in February 1948 that so intrigued Fortean Norman Markham.) The story of the cat and the canned salmon also suggests a sense of Fortean humor, one that was not too concerned over such niceties as “did it really happen.”

All in all, then, it’s hard to make much sense of Powell as a Fortean. Did he buy the theories? Did he have some certain interpretation of them? Did he see his own ideas as science and true, outside the Fortean discourse. Was Forteanism a joke—or was it a clue to undiscovered scientific laws? Impossible to say from the available evidence.

Based on his reading, Melanesian (and the related Polynesian) languages included a large number of loan words from Indonesian languages—words of great and intimate import—which suggested the need to rewrite the accepted history of the Pacific in order to posit a close relationship between Indonesian and Melanesian people. He thought that Indonesian people colonized the uninhabited islands of Melanesia and settled down, slowly diverging into a new, Polynesian culture. Later, a wave oaf “dark-skinned, fuzzy-haired people, speaking a Papuan language,” likely from New Guinea, overwhelmed the first colonizers. Because dark skin and fuzzy hair are genetically “dominant” (?), this physiognomy prevails. The Papuan language became dominant, chasing out all but the most intimate original words—and thus explaining the findings that Powell summarized.

Powell ended his essay acknowledging it was revolutionary and more exploratory than definitive. He also admitted he had no academic training in linguistics—unavailable in New Zealand at the time—and had only limited access to books on the Pacific languages. He hoped his enthusiasm would make up for some of these deficiencies, but was also open to criticism. Which he received. the following year, Dr. A Capell and Stefan Wurm separately disputed Powell’s conclusions, pointing out a number of facts which he had overlooked. Powell offered a rebuttal, but it took up only a few of those objections and insisted that other experts had vetted his ideas. The response suggested that he was not quite as open to criticism as his paper suggested. More, though, the general lack of response suggested how far out of the mainstream Powell was: his ideas need not even be engaged.

In late 1955, he published another piece, this one on his experiences teaching at Maori schools. His ideal for the schools was that a new, syncretic culture might emerge if the Maori were allowed to integrate the best of their cultural heritage with that of the European. That just wasn’t happening. Indeed, it was common that the younger generation was not learning Maori language at all—never mind the official changes that had occurred back in the 1940s. As a result, Maoria culture was declining, and would continue to decline without teachers specially trained in the language and culture. According to John Barrington’s Separate but Equal?: Maori Schools and the Crown 1867-1969, Powell’s article caused something of a controversy among school leaders. Judith A. Simon, Linda Tuhiwai Smith make a similar point, in their earlier A Civilising Mission?: Perceptions and Representations of the Native Schools System. The result seems to have been the same as his linguistic theorizing: a brief protest by authorities, followed by Fortean damning of his conclusions.

I do not know if Powell ever finished his studies. He was still at the Department of Anthropology in 1955, but that is the last I can find. But he seems to have continued his interest in Maori culture. In the 1960s, he helped James W. Ritchie in his work on Maori folklore “The Making of a Maori” and also received acknowledgments for aiding with “The Reed Book of Māori Mythology.”

I do not know when Powell was born or when he died.

*******

Nor do I know how Powell became associated with Fort, Forteanism, or the Fortean Society. His name appeared in five issues of Doubt, as well as the one letter from Thayer to Eric Frank Russell. These connections put him as part of the Society from 1947 to 1958, which covers his time teaching as well as most if not all of his time studying anthropology. The mentions in Doubt, though, are not guaranteed to be the same person due to Thayer’s idiosyncratic notation system.

The first time the name appeared was in Doubt 19 (October 1947) as part of a long paragraph of credits for people who had sent in material on flying saucers. It is worth noting that the name is spelled differently, with only one L: Powel. That may or may not have been a typographical error. The second mention also heaps speculation onto this whole speculative enterprise. Doubt 21, from June 1948, refers to an “A. E. Powell,” who—along with a number of other members—contributed a story about a rain the color of “lime soda pop” in Dayton, Ohio. Probably that’s some one different, but, if so, it is the only mention of a Powell with those initials in the run of Doubt.

Only with references beginning in 1953 are we on firmer ground. Issue 39 (January 1953) had three mentions, both of whom refer to the Kiwi Guy Powell. On page 180, in Thayer’s run down of the best contributions for the quarter, he notes that “Powell from New Zealand” sent in two articles from the Dunedin Evening Star. The first, a wire story, is a version of an urban legend that continues to circulate: a hostess fed her guests canned salmon, then left the can n the porch for her cat; later she found the cat dead. All the guests were given ptomaine and had their stomach pumps. Some time afterward, a neighbor told the woman her cat had been hit b a car and he had set it on the porch for her, but didn’t ring because he didn’t want to ruin the party. The second was a report on H. H. Nininger, who directed the American Meteorite Museum in Arizona. He found a glass tunnel on the moon, several miles long, and was studying to see if it would be a good shelter for future explorers. Thayer quipped, “Let us know, Doc!” A page later, “G. Powell” was included among the long list of people who had contributed flying saucer material—which does give some credence to his being the one mentioned in 1947.

Powell again was among the contributors of Thayer’s favorite items four years later, when he next appeared, in Doubt 53 (February 1957). (The absence implies that he wasn’t a strongly committed member.) Powell’s piece again came from the Dunedin Evening Star and supplemented a report from E M G Hibbert of Tasmania, about a bull that was slaughtered, its skull opened, and . . . something found. The report was confused alternately saying it was a rat—on the word of two experienced slaughterman—unidentified and needing further study at the department of agriculture, and an embryo (though Thayer noted, presumably as a form of skepticism, there was no umbilical cord or placenta.) It is, of course, impossible to say at this late date, but the presence of undeveloped embryos attached to the brain of mammals is a rare phenomenon but not unknown. The condition goes by various names, a technical one being Craniopagus parasiticus.

A bit more than a year later, in Doubt 57 from July 1958, Powell’s name appeared twice more, though one of those mentions was not definitely him. That was a mention in a list of people who had contributed material on flying saucers and referred only to “Powell.” The other was Guy Powell. In a long column on weird falls, Thayer credited a Powell, who had contributed material from the Dunedin Evening Star. This article told of a series of strange rock falls in Pumphrey, Australia, over the course of three evenings, and then an entire day. The report appeared on 19 March 1957. What Thayer did not mention about the story was that it was a cause of dispute among different groups of Australian aboriginals.

That detail may seem insignificant, but it points to a broader issue in understanding Powell’s relationship to Forteanism. Assuming that I have the right Guy—sorry for the pun—he would seem to have certain interests that fit with the Fortean Society. Thayer was an advocate of aboriginal rights in America, championing the “Indian” cause. The Fortean Society also hosted bits on linguistic heterodoxy—such as American Indians speaking some northern European languages, and other ideas promulgated by German Forteans—theories that contradicted accepted historical narratives. Powell could seemingly have nestled his ideas in with these Fortean themes. But if he did, Thayer did not report it. Maybe it was just what drew him to the Society, and then he found other subjects worth pursuing.

Either way, what is striking is that his contributions to the Fortean Society do not seem to have related to his own research. (Although one is not sure what he may have said with the contribution of the last story on falls.) Rather, his more certain contributions display an interest in flying saucers or at least odd aerial phenomena. (Again, Thayer’s editorial judgment makes it impossible to tell what point Powell was trying to communicate.) He also contributed more typical Fortean anomalies—the animal in the bull’s head (which was probably explicable) and strange rains of objects. The story about the glass tunnel burrowed into the surface of the moon by a meteorite may suggest that Powell was as skeptical as Thayer (and Fort!) of astronomers—and, in this case, rightly so. (Nininger was otherwise a respected amateur, and was also involved in investigating the weird explosion over Kansas in February 1948 that so intrigued Fortean Norman Markham.) The story of the cat and the canned salmon also suggests a sense of Fortean humor, one that was not too concerned over such niceties as “did it really happen.”

All in all, then, it’s hard to make much sense of Powell as a Fortean. Did he buy the theories? Did he have some certain interpretation of them? Did he see his own ideas as science and true, outside the Fortean discourse. Was Forteanism a joke—or was it a clue to undiscovered scientific laws? Impossible to say from the available evidence.