Willets, 1925

Willets, 1925 A Fortean of tremendous accomplishment, whose life is fully told, except for the parts most relevant to his Forteanism.

Gilson VanderVeer Willets was born in New York City on 19 November 1898. His father, also named Gilson Willets, was an author; in 1904, he exchanged letters with the Fortean founder Booth Tarkington. Willets’ moth was Daisy May VanderVeer, known in the family as Dean. In 1900, the Willets lived with Dean’s father, John Vanderveer, a manufacturer. The New York census from five years later still had the Willets living with Gilson’s maternal grandparents, but now in Bedford, New York. Apparently, they were well off. Gilson recalled that he attended St. Anne’s Academy before moving on to the New York Military Academy, a private institution near West Point.

Gilson would later say that he learned Morse code before he turned ten, which would prove prophetic for his future careers. The timeline of his life does get a bit messy after 1910, though. That year the census had him, aged 11, living with his grandparents, now in New Castle, New York (which is in the same county as Bedford: Westchester.) His father was not with the family at the time. The New York census for 1915 has him living as a lodger in Yonker, attending school. According to one article from a later date (preserved in a clipping file at the San Jose History Museum), he set up a one KW radio station in his room, with the call letters GW. He was tall and strong, 6’3” and 225 pounds. Other articles from the same source have him leaving school and heading out to sea in 1914; one even has him working with the radio pioneer Lee De Forest in that year. A family history on ancestry.com has him marrying in November 1917. I cannot verify that, but it is true that in the 1930 census he put down his age at first marriage as 19, which would track.

Gilson VanderVeer Willets was born in New York City on 19 November 1898. His father, also named Gilson Willets, was an author; in 1904, he exchanged letters with the Fortean founder Booth Tarkington. Willets’ moth was Daisy May VanderVeer, known in the family as Dean. In 1900, the Willets lived with Dean’s father, John Vanderveer, a manufacturer. The New York census from five years later still had the Willets living with Gilson’s maternal grandparents, but now in Bedford, New York. Apparently, they were well off. Gilson recalled that he attended St. Anne’s Academy before moving on to the New York Military Academy, a private institution near West Point.

Gilson would later say that he learned Morse code before he turned ten, which would prove prophetic for his future careers. The timeline of his life does get a bit messy after 1910, though. That year the census had him, aged 11, living with his grandparents, now in New Castle, New York (which is in the same county as Bedford: Westchester.) His father was not with the family at the time. The New York census for 1915 has him living as a lodger in Yonker, attending school. According to one article from a later date (preserved in a clipping file at the San Jose History Museum), he set up a one KW radio station in his room, with the call letters GW. He was tall and strong, 6’3” and 225 pounds. Other articles from the same source have him leaving school and heading out to sea in 1914; one even has him working with the radio pioneer Lee De Forest in that year. A family history on ancestry.com has him marrying in November 1917. I cannot verify that, but it is true that in the 1930 census he put down his age at first marriage as 19, which would track.

WIlson, 1948

WIlson, 1948 And all the other facts from the various articles do seem to be correct; it is jus the chronology that is confused. Sometime before the outbreak of World War I, he did head out to sea, apparently first aboard the El Oriente. He worked his way around the world on various ships and to various countries as a wireless operator. The reminisces, which is all the sourcing we have for this time, makes him out to be like a character in his father’s stories, a bodyguard for a Russian prince, a soldier of fortune in Central America, a ramp through the tropics—three years at sea, all told. According to one report, when America declared war on Germany, in April 1917, he was in Mexico doing confidential work for the Mexican government. That’s not to say any of these reports are wrong, just unverified. (One is reminded one another Fortean, Odo B. Stade, who said that he fought with Pancho Villa’s troops during this same period.)

Whatever is made of that confusion, Willets did register for the draft, in September 1918—three months before the armistice. At the time, he was living in New York with Phylis Willets, presumably his wife, and working as a radio instructor at a YMCA radio School. Contemporary and later reports agree that he served some time at Camp Martin, Tulane University; he may have been a chief instructor in the signal corps. There are also unsubstantiated reports that he may have served some in France, as well. It seems clear that it was around this time—probably just before the war—that he met Lee De Forest and worked with him in Highbridge, New York, building radio-telephones for the navy.

In 1919, according to a ship log, he was aboard the Esperanza, returning to New York from Cuba, which supports later claims—also from clippings held in the San Jose History Museum—that after the war he spent some three years traveling around the world again, setting up radio stations in Europe, Central and South America. The 1920 census is unclear on this matter—he was in New York at the time, yet listed as a seaman. He was single. Over the next several years, he also traveled throughout the U.S., according to those same articles, spending time in Providence, Rhode Island, Detroit, Toledo, Cincinnati, and St. Louis, working everywhere as a radio operator—what Fortean Harry Leon Wilson called a “good loose trade,” a job that was needed everywhere and allowed him to travel without being tied down. In 1922, his father died.

That same year, he found himself, according to contemporary reports, in St. Joseph, Missouri, where he established the state radio station, WOS. The following year, he moved to Davenport, Iowa, where he helped establish a radio station for the Palmer Chiropractic school, WOC—linking him to the alternative medicine of the time that lurked int he background of many Forteans of his era and older. WOC would become a superstation—heard for miles around—allowing him to broadcast even from the Sears Tower in Chicago one time. He organized a radio research club. Around August of 1923, he began broadcasting a show—every morning, at nine or ten am, reports differ—on household hints and cooking. Willets considered himself an excellent cook who had a lot to teach housewives. At the time, he was known on the air as GWW—why the second W and not a V is unknown. At some point, he also picked up the nickname Rex, as in Radio Rex. As a result of his show, the radio station received numerous recipes, and Willets compiled these into a book that the school sold.

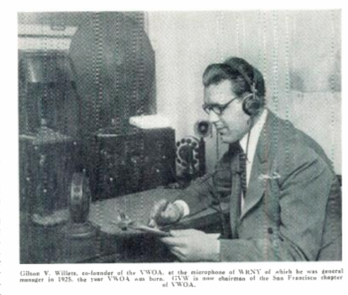

The ancestry.com family history has him marrying a second time in 1923, Anne Burke Conlan; the marriage was in St. Joseph, in September. Four months later, Anne gave birth to their daughter, Thuvia. Family life did not slow Willets. In the summer of 1924 he and a radio engineer took a 268 mile canoeing trip from Turtle Creek, Wisconsin, back to Davenport. But even that did not quell his itchy feet. In early 1925, he announced his departure from WOC; he was headed back to New York, where he would build WRNY for Hugo Gernsback—yes, Hugo Gernsback, the father of modern science fiction was fascinated by electronics and radio. I do not know if Willets had any interest in science fiction but there is, on the used book market, a signed copy of Gernsback’s Ralph 124c 41 (1925), with Willets’ bookplate pasted in it. WRNY broadcast from the Roosevelt Hotel. According to the 1925 New York census, he was living in Queens with his family, Anne and Thuvia. In 1925, he helped to organize the Veteran Wireless Operators Association.

Neither his family nor New York could hold him, though. In later recollections, he would say it was becoming clear to him, around this time, that he would never find fame and fortune as a radio operator. Still, he allowed himself to be enticed by Hamilton Holt of Rollins College to manage Central Florida Broadcasting, WDBO. After a year, he left for San Francisco, where he was hoped to give up radio engineering and become a writer—why San Francisco is unknown. He ended up doing a bit more radio work there anyway, working at and eventually managing KFWI. He also did some time in the water, aboard the Yale and Harvard as a radio operator. In time, he got his chance at writing, though, later biographical pieces saying that he became a columnist for the San Francisco News. He had a literary mentor, the novelist Peter B. Kyne—and that may be why he came to San Francisco, if the two had met before. A long-time San Francisco resident, Kyne may also have helped Willets become established.

Around this time, Willets developed a new hobby—he was a man of passionate enthusiasms, of that there is little doubt. Willets was keen on contests. According to the history “The Contest Story,” Kyne suggested that Willets devote his column to the subject, and for the next three years Willets put out a daily column devoted to announcements, criticism, and reviews of various contests—it was called “The National Contest News.” Supposedly, magazines in Britain and the United States reprinted some of the columns. In 1928, with 11 other men, he founded the National Contest Forum, writing a constitution, bylaws, and adopting an insignia. Some time around here, he also started calling his home the “International Contest Headquarters.” In 1930, his column went weekly and he announced a yearly award for an “All-America Group of ConteSTARS”: the ten best contests each year. In 1934, he wrote the introduction to the book “Contest Gold.”

According to the 1930 census, he considered himself a fiction author—although I have found no examples of his fiction writing—and listed himself as widowed; Anne and Thuvia, though, at least according to the 1940 census, were still alive, and living in New York. At any rate, just as he’d found a new hobby, Willets had found a new love—the love proving more enduring than his hobby. Bernice Brown did contests as a hobby, especially those dealing with Hollywood. Somehow they met—she may have even been instrumental in getting Willets involved with contests, encouraging him to enter one in which he won $5,000 and perhaps encouraging him to write about columns in his column. They married in the late 1920s or early 1930s and seem to have never had children.

Even so, Willets didn’t quite give up on his last interests. He continued to write letters and articles for electronics publications. And during the Golden Gate International Exposition—when fellow San Francisco Fortean Robert Barbour Johnson displayed his paintings of circus scenes—Willets sponsored Lee De Forest Day. Apparently, though, the decade was mostly spent cranking out his weekly column. I cannot find him in the 1940 census, for whatever reason.

His life’s direction took another turn during World War II. He became fascinated by Father Flanagan, proprietor of Boys Town. In 1943, he wrote a glowing article, referencing the Spencer Tracy movie made a few years earlier. That year, too, he closed up his contest column when he was invited to spend a year in Nebraska with the Father gathering material for a biography. He returned to San Francisco in 1944 and did write up the story; it was never published, though, and instead was incorporated into Oursler and Oursler’s Father Flanagan of Boys Town, which came out a few years later. Supposedly, he also did some work for the Office of Price Administration, the United Nations Ration Board, and served as secretary of the Irving Street Merchants Association.

These seem to have been mostly ceremonial and, in any case, Willets had to give up all but the Merchants Association by 1946. According to contemporaneous reports, he was very ill for about three years, from 1944 to 1947, and had to undergo operations. I can find no information on the nature of his illness, though.

The rest of Willets life is not well documented. By 1948, he seems to have finished his convalescence and gave up the Merchants Association. Some time thereafter he moved out of San Francisco and north to a redwood-shrouded property along the Russian River. He was a charter member of the Lee De Forest Pioneers and, indeed, hosted De Forest at his rural home. In 1955, the area was subject to horrendous flooding. Willets made the paper where he was credited a a civil defense director—Willets loved his organizations. He requested the air force send aid to the area, especially in rescuing people. Willets’ mother died in 1967. In 1971, he was writing about stamps for the American Revenuer, indicating yet another hobby. His second wife, Anne, died in 1977; Bernice, his third wife, died in 1979.

Both outlived Gilson Willets. He died 7 January 1976, aged 77.

Whatever is made of that confusion, Willets did register for the draft, in September 1918—three months before the armistice. At the time, he was living in New York with Phylis Willets, presumably his wife, and working as a radio instructor at a YMCA radio School. Contemporary and later reports agree that he served some time at Camp Martin, Tulane University; he may have been a chief instructor in the signal corps. There are also unsubstantiated reports that he may have served some in France, as well. It seems clear that it was around this time—probably just before the war—that he met Lee De Forest and worked with him in Highbridge, New York, building radio-telephones for the navy.

In 1919, according to a ship log, he was aboard the Esperanza, returning to New York from Cuba, which supports later claims—also from clippings held in the San Jose History Museum—that after the war he spent some three years traveling around the world again, setting up radio stations in Europe, Central and South America. The 1920 census is unclear on this matter—he was in New York at the time, yet listed as a seaman. He was single. Over the next several years, he also traveled throughout the U.S., according to those same articles, spending time in Providence, Rhode Island, Detroit, Toledo, Cincinnati, and St. Louis, working everywhere as a radio operator—what Fortean Harry Leon Wilson called a “good loose trade,” a job that was needed everywhere and allowed him to travel without being tied down. In 1922, his father died.

That same year, he found himself, according to contemporary reports, in St. Joseph, Missouri, where he established the state radio station, WOS. The following year, he moved to Davenport, Iowa, where he helped establish a radio station for the Palmer Chiropractic school, WOC—linking him to the alternative medicine of the time that lurked int he background of many Forteans of his era and older. WOC would become a superstation—heard for miles around—allowing him to broadcast even from the Sears Tower in Chicago one time. He organized a radio research club. Around August of 1923, he began broadcasting a show—every morning, at nine or ten am, reports differ—on household hints and cooking. Willets considered himself an excellent cook who had a lot to teach housewives. At the time, he was known on the air as GWW—why the second W and not a V is unknown. At some point, he also picked up the nickname Rex, as in Radio Rex. As a result of his show, the radio station received numerous recipes, and Willets compiled these into a book that the school sold.

The ancestry.com family history has him marrying a second time in 1923, Anne Burke Conlan; the marriage was in St. Joseph, in September. Four months later, Anne gave birth to their daughter, Thuvia. Family life did not slow Willets. In the summer of 1924 he and a radio engineer took a 268 mile canoeing trip from Turtle Creek, Wisconsin, back to Davenport. But even that did not quell his itchy feet. In early 1925, he announced his departure from WOC; he was headed back to New York, where he would build WRNY for Hugo Gernsback—yes, Hugo Gernsback, the father of modern science fiction was fascinated by electronics and radio. I do not know if Willets had any interest in science fiction but there is, on the used book market, a signed copy of Gernsback’s Ralph 124c 41 (1925), with Willets’ bookplate pasted in it. WRNY broadcast from the Roosevelt Hotel. According to the 1925 New York census, he was living in Queens with his family, Anne and Thuvia. In 1925, he helped to organize the Veteran Wireless Operators Association.

Neither his family nor New York could hold him, though. In later recollections, he would say it was becoming clear to him, around this time, that he would never find fame and fortune as a radio operator. Still, he allowed himself to be enticed by Hamilton Holt of Rollins College to manage Central Florida Broadcasting, WDBO. After a year, he left for San Francisco, where he was hoped to give up radio engineering and become a writer—why San Francisco is unknown. He ended up doing a bit more radio work there anyway, working at and eventually managing KFWI. He also did some time in the water, aboard the Yale and Harvard as a radio operator. In time, he got his chance at writing, though, later biographical pieces saying that he became a columnist for the San Francisco News. He had a literary mentor, the novelist Peter B. Kyne—and that may be why he came to San Francisco, if the two had met before. A long-time San Francisco resident, Kyne may also have helped Willets become established.

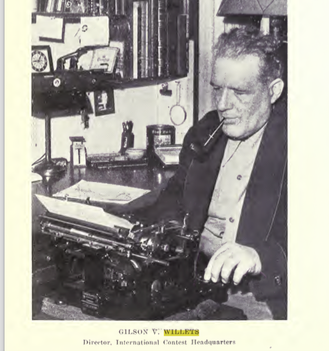

Around this time, Willets developed a new hobby—he was a man of passionate enthusiasms, of that there is little doubt. Willets was keen on contests. According to the history “The Contest Story,” Kyne suggested that Willets devote his column to the subject, and for the next three years Willets put out a daily column devoted to announcements, criticism, and reviews of various contests—it was called “The National Contest News.” Supposedly, magazines in Britain and the United States reprinted some of the columns. In 1928, with 11 other men, he founded the National Contest Forum, writing a constitution, bylaws, and adopting an insignia. Some time around here, he also started calling his home the “International Contest Headquarters.” In 1930, his column went weekly and he announced a yearly award for an “All-America Group of ConteSTARS”: the ten best contests each year. In 1934, he wrote the introduction to the book “Contest Gold.”

According to the 1930 census, he considered himself a fiction author—although I have found no examples of his fiction writing—and listed himself as widowed; Anne and Thuvia, though, at least according to the 1940 census, were still alive, and living in New York. At any rate, just as he’d found a new hobby, Willets had found a new love—the love proving more enduring than his hobby. Bernice Brown did contests as a hobby, especially those dealing with Hollywood. Somehow they met—she may have even been instrumental in getting Willets involved with contests, encouraging him to enter one in which he won $5,000 and perhaps encouraging him to write about columns in his column. They married in the late 1920s or early 1930s and seem to have never had children.

Even so, Willets didn’t quite give up on his last interests. He continued to write letters and articles for electronics publications. And during the Golden Gate International Exposition—when fellow San Francisco Fortean Robert Barbour Johnson displayed his paintings of circus scenes—Willets sponsored Lee De Forest Day. Apparently, though, the decade was mostly spent cranking out his weekly column. I cannot find him in the 1940 census, for whatever reason.

His life’s direction took another turn during World War II. He became fascinated by Father Flanagan, proprietor of Boys Town. In 1943, he wrote a glowing article, referencing the Spencer Tracy movie made a few years earlier. That year, too, he closed up his contest column when he was invited to spend a year in Nebraska with the Father gathering material for a biography. He returned to San Francisco in 1944 and did write up the story; it was never published, though, and instead was incorporated into Oursler and Oursler’s Father Flanagan of Boys Town, which came out a few years later. Supposedly, he also did some work for the Office of Price Administration, the United Nations Ration Board, and served as secretary of the Irving Street Merchants Association.

These seem to have been mostly ceremonial and, in any case, Willets had to give up all but the Merchants Association by 1946. According to contemporaneous reports, he was very ill for about three years, from 1944 to 1947, and had to undergo operations. I can find no information on the nature of his illness, though.

The rest of Willets life is not well documented. By 1948, he seems to have finished his convalescence and gave up the Merchants Association. Some time thereafter he moved out of San Francisco and north to a redwood-shrouded property along the Russian River. He was a charter member of the Lee De Forest Pioneers and, indeed, hosted De Forest at his rural home. In 1955, the area was subject to horrendous flooding. Willets made the paper where he was credited a a civil defense director—Willets loved his organizations. He requested the air force send aid to the area, especially in rescuing people. Willets’ mother died in 1967. In 1971, he was writing about stamps for the American Revenuer, indicating yet another hobby. His second wife, Anne, died in 1977; Bernice, his third wife, died in 1979.

Both outlived Gilson Willets. He died 7 January 1976, aged 77.

Willets, 1952

Willets, 1952 Willets' time as a Fortean was (seemingly) brief but intense, and it would be helpful to no more about it, especially to get an understanding of how Forteanism developed in San Francisco, but the sources just do not seem to be there.

I do not know when he first became aware of Fort, Forteanism, or the Fortean Society. There’s nothing in his biography to offer more than the slimmest of suggestions: perhaps he was a science fiction fan and read of Fort in the pulps, where he was frequently mentioned. (There were other Fortean radio enthusiasts, too, including Wallace A. Clemmons, and Thayer himself.) Of course, he could have come across his books, particularly after 1941, when the omnibus edition was put out. The connection might have also been through a friend. Kenneth MacNichol was another writer living in San Francisco, a veteran of the World War with a complicated love life, and the two might have known each other, MacNichol introducing Willets to Fort’s work.

Otherwise, Willets’ time as a Fortean seems to pretty much coincide with his illness, and so may have been something he took up to while away the hours of sickness.

The first mention of Willets’ Fortean activity was in Doubt 17 (March 1947), where he was listed among those who provide the most interesting clippings of the issue, though was referred to vaguely as “one MFS Willets.” The title does mean he had joined the Fortean Society already, though it is unknown when. His contribution was a clipping from the Catholic Universe Bulletin from 12 April 1946, which mocked the skull reconstruction of anthropologist T. Dale Stewart, then went on to attack evolution and Darwin. Thayer wrote that, while he was uncomfortable with the company, he had to join the Catholics in mocking the scientists—in his version, anti-evolution was baked into the Fortean cake, which is no doubt why W. L. McAtee was courted. A few pages later, Willets' name appeared again, this time tied to a clipping about a recent comet that Thayer was using as a basis to attack astronomers.

Apparently, Willets was devoted to the cause go questioning the limits of science—his clippings don’t reveal much, but they do show he was active and was skeptical of contemporary scientific consensuses. His name appeared in the following issue—Doubt 18, July 1947—attached to a clipping from the August 1946 True magazine about sea serpents. (Had Willets seen a sea serpent in his many travels?) The following issue—Doubt 19, October 1947—was devoted to flying saucers—Thayer hated the subject but felt he owed it to the membership—and Willets sent in something, but what is unclear, as Thayer grouped all the credits into a single paragraph. (The same lack of specificity applies to another clipping Willets sent in, also about flying saucers, that was reported in Doubt 21.)

There was no mention of Willets in Doubt 20, but that didn’t mean he’d given up on Forteanism. Quite the contrary, he was applying his organizing skills to the subject. Forteanism was to have a new outpost, on the West Coast. In Doubt 21, July 1948, Thayer announced the formation of “Chapter Two”:

“The San Francisco and Bay Area members have met informally as guests of MFS MacNichol, who shares honors for the idea with MFS Drussai and the labors of assembly with MFS di Gava. Gilson Willets presided and Wakefield kept the door. We do not have a complete roll call nor minutes, but all reports agree that the talk was high, wide and gratifying. The date--old style April 1.

“The members wrote their names in a book which--with unanimous approval--was named “The Book of the Damned.” Somebody brought up the subject of a ‘charter’ from ‘headquarters’ and the booing was gratifyingly terrific. (No, my lads, no charters and YS loves every boo in your bosoms.)

“Temporarily, the San Francisco Bay Area group is denominated only “Chapter Two of the Fortean Society.” The chances are they will give the Chapter a name at their next session. Perhaps this is a suitable use for the names of ‘posthumous Forteans.’ A list appeared in DOUBT No. 13, some additions in No. 15.”

MacNichol is given a lot of credit for Chapter Two, but others were involved, and there is some evidence that Willets was a driving force. In Jue 1948, C. Steven Bristol, a new Fortean, wrote to Don Bloch, one of Thayer’s steadfast Fortean supporters, and mentioned what was going on in San Francisco:

“A relative newcomer to Fortean ranks, I am somewhat in agreement with your point of having a private list of members, though there are obvious reasons for not issuing such a list. Somewhat along this line, FS members in California have opened up a Chapter of the Society in San Francisco, and have occasional meetings, more or less use-ing [sic] the meditations of FM Gillson Willets, with whom I recently had the pleasure of a meeting. It is an experiment which could be viewed with interest. Especially as the group is a cross representation of California’s ‘best.’”

And there’s the crux of irritation! What were Willets’ musings? There is no record, no information. Indeed, neither he nor the Chapter would last long.

The Chapter got irritated with Thayer—some even remember that Thayer had it disbanded, but this seems unlikely. Particularly irritating to them was Thayer’s politics, Pacifism, and theories that the second World War was a gigantic hoax cooked up by the powers-that-be. By the end of 1948, there was no more Chapter Two.

And after 1948, Willets’s name would no longer appear in Doubt; indeed, I can find no more references to his Forteanism at all after this date. As with the others, he may have been irritated at Thayer's lack of patriotism--Thayer hated the Civil Defense, which Willets joined.

In December 1948, Doubt 23, his name appeared twice. One was in reference to the celebrated Fortean personage Wonet. The other had something to do with flying saucers. In both cases, though, Willets’ name was provided in a long list of other names and so the exact story he sent in, and, indeed, his ideas about those stories remain (frustratingly) unknown.

I do not know when he first became aware of Fort, Forteanism, or the Fortean Society. There’s nothing in his biography to offer more than the slimmest of suggestions: perhaps he was a science fiction fan and read of Fort in the pulps, where he was frequently mentioned. (There were other Fortean radio enthusiasts, too, including Wallace A. Clemmons, and Thayer himself.) Of course, he could have come across his books, particularly after 1941, when the omnibus edition was put out. The connection might have also been through a friend. Kenneth MacNichol was another writer living in San Francisco, a veteran of the World War with a complicated love life, and the two might have known each other, MacNichol introducing Willets to Fort’s work.

Otherwise, Willets’ time as a Fortean seems to pretty much coincide with his illness, and so may have been something he took up to while away the hours of sickness.

The first mention of Willets’ Fortean activity was in Doubt 17 (March 1947), where he was listed among those who provide the most interesting clippings of the issue, though was referred to vaguely as “one MFS Willets.” The title does mean he had joined the Fortean Society already, though it is unknown when. His contribution was a clipping from the Catholic Universe Bulletin from 12 April 1946, which mocked the skull reconstruction of anthropologist T. Dale Stewart, then went on to attack evolution and Darwin. Thayer wrote that, while he was uncomfortable with the company, he had to join the Catholics in mocking the scientists—in his version, anti-evolution was baked into the Fortean cake, which is no doubt why W. L. McAtee was courted. A few pages later, Willets' name appeared again, this time tied to a clipping about a recent comet that Thayer was using as a basis to attack astronomers.

Apparently, Willets was devoted to the cause go questioning the limits of science—his clippings don’t reveal much, but they do show he was active and was skeptical of contemporary scientific consensuses. His name appeared in the following issue—Doubt 18, July 1947—attached to a clipping from the August 1946 True magazine about sea serpents. (Had Willets seen a sea serpent in his many travels?) The following issue—Doubt 19, October 1947—was devoted to flying saucers—Thayer hated the subject but felt he owed it to the membership—and Willets sent in something, but what is unclear, as Thayer grouped all the credits into a single paragraph. (The same lack of specificity applies to another clipping Willets sent in, also about flying saucers, that was reported in Doubt 21.)

There was no mention of Willets in Doubt 20, but that didn’t mean he’d given up on Forteanism. Quite the contrary, he was applying his organizing skills to the subject. Forteanism was to have a new outpost, on the West Coast. In Doubt 21, July 1948, Thayer announced the formation of “Chapter Two”:

“The San Francisco and Bay Area members have met informally as guests of MFS MacNichol, who shares honors for the idea with MFS Drussai and the labors of assembly with MFS di Gava. Gilson Willets presided and Wakefield kept the door. We do not have a complete roll call nor minutes, but all reports agree that the talk was high, wide and gratifying. The date--old style April 1.

“The members wrote their names in a book which--with unanimous approval--was named “The Book of the Damned.” Somebody brought up the subject of a ‘charter’ from ‘headquarters’ and the booing was gratifyingly terrific. (No, my lads, no charters and YS loves every boo in your bosoms.)

“Temporarily, the San Francisco Bay Area group is denominated only “Chapter Two of the Fortean Society.” The chances are they will give the Chapter a name at their next session. Perhaps this is a suitable use for the names of ‘posthumous Forteans.’ A list appeared in DOUBT No. 13, some additions in No. 15.”

MacNichol is given a lot of credit for Chapter Two, but others were involved, and there is some evidence that Willets was a driving force. In Jue 1948, C. Steven Bristol, a new Fortean, wrote to Don Bloch, one of Thayer’s steadfast Fortean supporters, and mentioned what was going on in San Francisco:

“A relative newcomer to Fortean ranks, I am somewhat in agreement with your point of having a private list of members, though there are obvious reasons for not issuing such a list. Somewhat along this line, FS members in California have opened up a Chapter of the Society in San Francisco, and have occasional meetings, more or less use-ing [sic] the meditations of FM Gillson Willets, with whom I recently had the pleasure of a meeting. It is an experiment which could be viewed with interest. Especially as the group is a cross representation of California’s ‘best.’”

And there’s the crux of irritation! What were Willets’ musings? There is no record, no information. Indeed, neither he nor the Chapter would last long.

The Chapter got irritated with Thayer—some even remember that Thayer had it disbanded, but this seems unlikely. Particularly irritating to them was Thayer’s politics, Pacifism, and theories that the second World War was a gigantic hoax cooked up by the powers-that-be. By the end of 1948, there was no more Chapter Two.

And after 1948, Willets’s name would no longer appear in Doubt; indeed, I can find no more references to his Forteanism at all after this date. As with the others, he may have been irritated at Thayer's lack of patriotism--Thayer hated the Civil Defense, which Willets joined.

In December 1948, Doubt 23, his name appeared twice. One was in reference to the celebrated Fortean personage Wonet. The other had something to do with flying saucers. In both cases, though, Willets’ name was provided in a long list of other names and so the exact story he sent in, and, indeed, his ideas about those stories remain (frustratingly) unknown.