This story had my Spidey-sense tingling, even when I had yet to nail down a lot of details. As more information came in, I felt both justified—and frustrated. I think there’s a really interesting tale here, with some meaty connections, but just not enough detail, and so what’s left is even more vague than other chronicles of Forteans—never rising to the level of suggestive, just tantalizing.

Gertrude Martin was likely born in England or Ireland around 1886. She moved to the U.S., married and naturalized by 1903—when she was only 17. Her husband was Horace Hills, 12 years her senior, an automobile and bicycle enthusiast, and descendant of James Hills, who had fought in the Revolutionary War. They had a son in 1905, Horace Babcock Hills, third by that name.

Gertrude Martin was likely born in England or Ireland around 1886. She moved to the U.S., married and naturalized by 1903—when she was only 17. Her husband was Horace Hills, 12 years her senior, an automobile and bicycle enthusiast, and descendant of James Hills, who had fought in the Revolutionary War. They had a son in 1905, Horace Babcock Hills, third by that name.

In 1917, she was widowed—a state that does not seem to have distressed her much—when Horace died after a brief bout with pneumonia. At the time, the family had been living in Philadelphia, Horace working for the Standard Steel Car Co. By 1920, she relocated to Boston, where she and her son rented a room; the census says that she was an author. And indeed there are several pamphlet-sized writings in the ‘20s and ‘30s credited to Gertrude Hills, none of which I have seen: Christmas Greetings (1924); Christmas is the Fairest of Her Jewels (1925); I Cannot Reach the Crown of Him (1927); To Zimbalist (1931); Procession: To a Cedar of Lebanon Standing Alone in a Field of Flushing: For Edward L. Stone (1931); With Arms Like These! (1938). They seem to be poems. Later, she said she was dissuaded from further writing poetry when she read Amy Lowell, who won the Pulitzer prize posthumously in 1926.

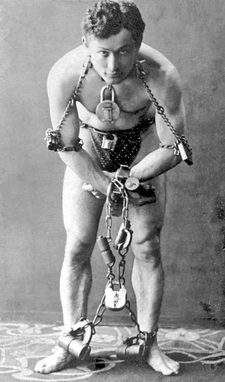

That was the year Hills likely returned to New York City; the NY state census does not have her there in 1925, but Boston’s City directory does. If that is indeed when she moved, Hills acted quickly in New York. She went to work for Dauber and Pine booksellers on 5th Avenue, and discovered—apparently in a pile of pamphlets—a first edition of Poe’s Murder in the Rue Morgue, which subsequently sold for $25,000 (about 330,000 in today’s dollars). She also arranged for Harry Houdini to perform at a charitable event in the summer. They had been friends since 1922, it seems. They became close enough that she remembered, later, they would play a game while walking through the city: ‘when we came to shop window he would always stop, make me look at the display for one minute, then close my eyes and tell him what I had seen.’ He inscribed one of his books to her, calling her his friend.

Exactly how Hills and Houdini became acquainted, and the nature of their relationship is unclear. She would have been in her late thirties then; Houdini was about a decade older, and had spent a lot of time in England—which may have been one connection. Hills’s request for Houdini to perform came just at the moment that Houdini took an interest in charity. Biographer Jim Steinmeyer supposes that Houdini turned to charity in emulation of his competitor and colleague, Howard Thurston. Hills suspected that an injury Houdini suffered during the charitable performance led to his death later that year, in November. She counseled Sir Arthur Conan Doyle—creator of Sherlock Holmes, friend of Houdini, and believer in spiritualists—not to worry over much about Houdini’s passing. The letter further indicated the depth of the relationship, as Hills saw it, and points to the connection she and the magician had:

“Our morning papers quote you as saying that Houdini’s mother’s spirit foresaw his death and that you witheld [sic] the message, hoping that it would prove wrong.

Perhaps it would interest you to learn that Houdini did not fear death, in fact, he foretold his own death to me four years ago, and has discussed it with me many times since. The last but one time we met. he told me in detail how he wished his funeral conducted, spoke of spiritual things and told me that he would not raise a finger to detain him one moment from joining his mother. The last time I saw him—just before starting on his tour—we said goodby [sic] to each other for always. As he looked at me in parting, suddenly his coming death was revealed to me—he also saw what I saw; so we parted.

No one need regret that he was sent for—he would not return if he could, I think, for he was spiritually lonely. He was an old spirit, a spirit at one with the Source of Life, and the Source of Life was of such stupendous magnitude to him that he stood in awe before it. It was his magnificent conception of the Power of the Universe that could not permit him to accept the mediums’ attitude toward the dead. To him their results were trivial. Strange as it may seem, Houdini was diffident and shy about opening the door to his soul to his friends. To me, however, the door was opened wide because he found in me one that had suffered as much as he had spiritually, and he knew that I could interpret what I saw there.

Houdini spoke of you often, always so kindly; but he could not understand how you could believe that the manifestations of mediums were anything but subconscious activity. I wish that I could believe the dead communicate with us, for I know that Houdini would send a message to me, or rather, a reply that was not made before he left. My own lack of interest in the subject has lain in the fact that until he sided I had lost no one by death that I wished to hear from again. [So much for Horace!]

If you do not know what caused our friend’s death, you will be interested to learn that he injured himself this summer while presenting for charity his straight jacket act. The injury was not taken seriously by himself, or his physician, I imagine, since the pain resulting from it was diagnosed as forms of ‘indigestion.’

Although she could not have known it, Hills’ association with Houdini embedded her in a Fortean nexus. Houdini’s competitor, Howard Thurston, had employed future Fortean Fred Keating. (Thayer himself was an amateur magician.) The summer that Houdini was performing at Hills’s event, he was also taking on the soi-disant Indian mystic Rahman Bey, who had come to prominence, in part, through the machinations of another future Fortean, Hereward Carrington. Magic, even when consciously done as pure trickery, was one way to generate wonder in a secular universe—see Simon During, Modern Enchantments: The Cultural Power of Secular Magic—and so was contemplating Fortean phenomena.

This attachment to wonder and transcendence, while acknowledging science’s power as a revealer of truths seems to undergird Hills’s faith, at least as described in this letter, which seems vaguely New Thought-ish. Perhaps she was even influenced by Theosophy, an important belief-system in Fortean circles. Fort was still alive at the times of these events—still to publish his final two books—and probably would not have countenanced the connection of his ideas to those of Theosophy or New Thought. Her vision of the future—and Houdini’s vision?—though, he might have classed as an example of a Wild Talent—if he knew about it when he wrote that tome—which puts her squarely in the Fortean fold. She was intrigued by wonder, drawn to the mysterious—yet distrustful of both.

Sometime in the very early 1930s—probably before the Fortean Society was even founded—Hills was hired by Edwin Beinecke as an assistant in collecting materials of—and about—Robert Louis Stevenson. Newspapers noted Hills had “catalogued the libraries of many notable Americans—which probably referred to her work with Pine and Dauber, as they purchased entire estates. “Their joint hunt through the years and through many countries has assembled a mass of Stevenson material, including portraits, first editions, publishers’ manuscripts and especially a priceless series of Stevenson’s letters long buried in England and Scotland—material which will be indispensable for any future reconstruction of the real Stevenson.” Beinecke’s collection, in turn, would go to the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale.

Later, Hills’s would have a less glamorous memory of her work under the heir to a trading stamps fortune. In 1955, she told Yale’s librarian, “When I tried to form a Stevenson Research Library for Beinecke, though warned of his [ignorance?], vanity & treachery, I felt with my family & contacts it cd be done—I worked for virtually nothing, assisted [financially?] by my son, my mother-in-law, & other clients—hoping to make a splendid biographical-bibliographical catalog—but it was all in vain—he wdn’t even let me have a typist! All he wanted was 15 ‘stars’ as a great collector; but that was of course impossible, When he took up with a scavenger on the [outer?] rim of commercial art world, I was disillusioned, left. This man persuaded him the RLS collection was [?] & he cd made like another J. P. Morgan!” All the contacts in England, she insisted, had been hers—not Beinecke’s. (To the librarian’s credit, the letter ended up at Beinecke, too.)

Some contemporaneous evidence suggests that Hills was less than happy working for Beinecke. In 1934, she read A Cowman’s Wife, by Arizona rancher Mary Kidder Rak, and wrote the author a fan letter, telling her of how she wished that she could live the life of a rancher. The two struck up an epistolary friendship that lasted into the 1940s. Only Rak’s side survives, but it suggests that Hills complained about Beinecke. She also had some health issues that made her distrust doctors—part of what seems to be a general distrust of those in charge at the time. A staunch Republican, she disliked FDR and his New Deal. After leaving Beinecke’s employ, she turned again to writing, mystery stories now, rather than poetry, but none ever seemed to have been published. The 1940 census has her making a living as a secretary for an insurance company. She seems to have experienced many disappointments in her forties and early fifties.

Gertrude M. Hills likely died in 1960.

Her time with the Fortean Society was brief, the interactions minor. Her name appeared in issue 7, June 1943, listed among those who contributed material which Thayer did not have space to consider. After that, she appeared twice more, in issues 9 (1944) and 11 (1944-45), the first one proving the Hills writing to Thayer was also the one who worked for Beinecke. Thayer called his correspondent a “long-time Fortean, bibliophile, book cataloguer, and Stevenson expert.” How she came to the Fortean Society is not clear—Thayer was also a book collector, and so the two may have come in contact that way. Fred Keating may also have put Hills in contact with the Fortean Society.

The first clipping that Thayer mentioned concerned the sale of 9,000 items of White House correspondence from the files of Edward T. Clark, private secretary to Calvin Coolidge. According to the Publisher’s Weekly, a journalist who was looking at the material pre-sale found something that sparked a discussion and, subsequently, the cancellation of the sale as it would be ‘most unfortunate if the letters and papers fell into the hands of unpatriotic persons.” Instead, the material was handed over to the Library of Congress, on the condition that it be sealed for twenty years. Thayer editorialized:

“That’s the beauty of living in a democracy. The public servants are accountable at all times to the electorate for all their acts in office, and you may trust that great institution, the public-spirited Freeprez , to ferret out the news and print it without fear or favor. . . . Altogether, boys!”

Hills’s final contribution to the Society was a book, Francis R. Fast’s Houdini Messages. This was a book that claimed that a spiritual medium had reached Houdini in the after-life, and Houdini had repudiated all of his previous work. The proof was later shown to be built of a tissue of lies and fakery. Hills’s point in providing this book is not clear—did she believe it? Was she just clearing her shelves? There is too little information to make a conclusion

Hills was an interesting character, embedded in Fortean networks of the 1920s, but without further information, it is hard to characterize her Forteanism.

That was the year Hills likely returned to New York City; the NY state census does not have her there in 1925, but Boston’s City directory does. If that is indeed when she moved, Hills acted quickly in New York. She went to work for Dauber and Pine booksellers on 5th Avenue, and discovered—apparently in a pile of pamphlets—a first edition of Poe’s Murder in the Rue Morgue, which subsequently sold for $25,000 (about 330,000 in today’s dollars). She also arranged for Harry Houdini to perform at a charitable event in the summer. They had been friends since 1922, it seems. They became close enough that she remembered, later, they would play a game while walking through the city: ‘when we came to shop window he would always stop, make me look at the display for one minute, then close my eyes and tell him what I had seen.’ He inscribed one of his books to her, calling her his friend.

Exactly how Hills and Houdini became acquainted, and the nature of their relationship is unclear. She would have been in her late thirties then; Houdini was about a decade older, and had spent a lot of time in England—which may have been one connection. Hills’s request for Houdini to perform came just at the moment that Houdini took an interest in charity. Biographer Jim Steinmeyer supposes that Houdini turned to charity in emulation of his competitor and colleague, Howard Thurston. Hills suspected that an injury Houdini suffered during the charitable performance led to his death later that year, in November. She counseled Sir Arthur Conan Doyle—creator of Sherlock Holmes, friend of Houdini, and believer in spiritualists—not to worry over much about Houdini’s passing. The letter further indicated the depth of the relationship, as Hills saw it, and points to the connection she and the magician had:

“Our morning papers quote you as saying that Houdini’s mother’s spirit foresaw his death and that you witheld [sic] the message, hoping that it would prove wrong.

Perhaps it would interest you to learn that Houdini did not fear death, in fact, he foretold his own death to me four years ago, and has discussed it with me many times since. The last but one time we met. he told me in detail how he wished his funeral conducted, spoke of spiritual things and told me that he would not raise a finger to detain him one moment from joining his mother. The last time I saw him—just before starting on his tour—we said goodby [sic] to each other for always. As he looked at me in parting, suddenly his coming death was revealed to me—he also saw what I saw; so we parted.

No one need regret that he was sent for—he would not return if he could, I think, for he was spiritually lonely. He was an old spirit, a spirit at one with the Source of Life, and the Source of Life was of such stupendous magnitude to him that he stood in awe before it. It was his magnificent conception of the Power of the Universe that could not permit him to accept the mediums’ attitude toward the dead. To him their results were trivial. Strange as it may seem, Houdini was diffident and shy about opening the door to his soul to his friends. To me, however, the door was opened wide because he found in me one that had suffered as much as he had spiritually, and he knew that I could interpret what I saw there.

Houdini spoke of you often, always so kindly; but he could not understand how you could believe that the manifestations of mediums were anything but subconscious activity. I wish that I could believe the dead communicate with us, for I know that Houdini would send a message to me, or rather, a reply that was not made before he left. My own lack of interest in the subject has lain in the fact that until he sided I had lost no one by death that I wished to hear from again. [So much for Horace!]

If you do not know what caused our friend’s death, you will be interested to learn that he injured himself this summer while presenting for charity his straight jacket act. The injury was not taken seriously by himself, or his physician, I imagine, since the pain resulting from it was diagnosed as forms of ‘indigestion.’

Although she could not have known it, Hills’ association with Houdini embedded her in a Fortean nexus. Houdini’s competitor, Howard Thurston, had employed future Fortean Fred Keating. (Thayer himself was an amateur magician.) The summer that Houdini was performing at Hills’s event, he was also taking on the soi-disant Indian mystic Rahman Bey, who had come to prominence, in part, through the machinations of another future Fortean, Hereward Carrington. Magic, even when consciously done as pure trickery, was one way to generate wonder in a secular universe—see Simon During, Modern Enchantments: The Cultural Power of Secular Magic—and so was contemplating Fortean phenomena.

This attachment to wonder and transcendence, while acknowledging science’s power as a revealer of truths seems to undergird Hills’s faith, at least as described in this letter, which seems vaguely New Thought-ish. Perhaps she was even influenced by Theosophy, an important belief-system in Fortean circles. Fort was still alive at the times of these events—still to publish his final two books—and probably would not have countenanced the connection of his ideas to those of Theosophy or New Thought. Her vision of the future—and Houdini’s vision?—though, he might have classed as an example of a Wild Talent—if he knew about it when he wrote that tome—which puts her squarely in the Fortean fold. She was intrigued by wonder, drawn to the mysterious—yet distrustful of both.

Sometime in the very early 1930s—probably before the Fortean Society was even founded—Hills was hired by Edwin Beinecke as an assistant in collecting materials of—and about—Robert Louis Stevenson. Newspapers noted Hills had “catalogued the libraries of many notable Americans—which probably referred to her work with Pine and Dauber, as they purchased entire estates. “Their joint hunt through the years and through many countries has assembled a mass of Stevenson material, including portraits, first editions, publishers’ manuscripts and especially a priceless series of Stevenson’s letters long buried in England and Scotland—material which will be indispensable for any future reconstruction of the real Stevenson.” Beinecke’s collection, in turn, would go to the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale.

Later, Hills’s would have a less glamorous memory of her work under the heir to a trading stamps fortune. In 1955, she told Yale’s librarian, “When I tried to form a Stevenson Research Library for Beinecke, though warned of his [ignorance?], vanity & treachery, I felt with my family & contacts it cd be done—I worked for virtually nothing, assisted [financially?] by my son, my mother-in-law, & other clients—hoping to make a splendid biographical-bibliographical catalog—but it was all in vain—he wdn’t even let me have a typist! All he wanted was 15 ‘stars’ as a great collector; but that was of course impossible, When he took up with a scavenger on the [outer?] rim of commercial art world, I was disillusioned, left. This man persuaded him the RLS collection was [?] & he cd made like another J. P. Morgan!” All the contacts in England, she insisted, had been hers—not Beinecke’s. (To the librarian’s credit, the letter ended up at Beinecke, too.)

Some contemporaneous evidence suggests that Hills was less than happy working for Beinecke. In 1934, she read A Cowman’s Wife, by Arizona rancher Mary Kidder Rak, and wrote the author a fan letter, telling her of how she wished that she could live the life of a rancher. The two struck up an epistolary friendship that lasted into the 1940s. Only Rak’s side survives, but it suggests that Hills complained about Beinecke. She also had some health issues that made her distrust doctors—part of what seems to be a general distrust of those in charge at the time. A staunch Republican, she disliked FDR and his New Deal. After leaving Beinecke’s employ, she turned again to writing, mystery stories now, rather than poetry, but none ever seemed to have been published. The 1940 census has her making a living as a secretary for an insurance company. She seems to have experienced many disappointments in her forties and early fifties.

Gertrude M. Hills likely died in 1960.

Her time with the Fortean Society was brief, the interactions minor. Her name appeared in issue 7, June 1943, listed among those who contributed material which Thayer did not have space to consider. After that, she appeared twice more, in issues 9 (1944) and 11 (1944-45), the first one proving the Hills writing to Thayer was also the one who worked for Beinecke. Thayer called his correspondent a “long-time Fortean, bibliophile, book cataloguer, and Stevenson expert.” How she came to the Fortean Society is not clear—Thayer was also a book collector, and so the two may have come in contact that way. Fred Keating may also have put Hills in contact with the Fortean Society.

The first clipping that Thayer mentioned concerned the sale of 9,000 items of White House correspondence from the files of Edward T. Clark, private secretary to Calvin Coolidge. According to the Publisher’s Weekly, a journalist who was looking at the material pre-sale found something that sparked a discussion and, subsequently, the cancellation of the sale as it would be ‘most unfortunate if the letters and papers fell into the hands of unpatriotic persons.” Instead, the material was handed over to the Library of Congress, on the condition that it be sealed for twenty years. Thayer editorialized:

“That’s the beauty of living in a democracy. The public servants are accountable at all times to the electorate for all their acts in office, and you may trust that great institution, the public-spirited Freeprez , to ferret out the news and print it without fear or favor. . . . Altogether, boys!”

Hills’s final contribution to the Society was a book, Francis R. Fast’s Houdini Messages. This was a book that claimed that a spiritual medium had reached Houdini in the after-life, and Houdini had repudiated all of his previous work. The proof was later shown to be built of a tissue of lies and fakery. Hills’s point in providing this book is not clear—did she believe it? Was she just clearing her shelves? There is too little information to make a conclusion

Hills was an interesting character, embedded in Fortean networks of the 1920s, but without further information, it is hard to characterize her Forteanism.