The first of a series: Three Forteans in name only.

Tiffany Thayer was, among other things, a collector. He collected first issues of small magazines. He collected pamphlets. And, as the Canadian Theosophist said in a perfect capsule epitome of Thayer’s whole Fortean project: “The Fortean Society bids fair to become the greatest aggregation of Academic Cranks the world has known.” Three of those named by the Canadian Theosophist as evidence of Thayer’s plan are the subject of this posting: George Seldes, Norman Thomas, and Manly P. Hall. They all appeared in The Fortean Society Magazine or Doubt, with an MFS attached to their name—Member of the Fortean Society—but seemed inactive, unconcerned with Thayer or his aggregation of academic cranks. Indeed, they seem to have been more-or-less appointed to the Society because they were themselves academic cranks, and they continued their own work without much regard for the Society. They were Forteans in name only.

George Seldes was mentioned only once in the Fortean Society Magazine, issue 10 (Autumn 1944). But his publication, In Fact, was the apple of Thayer’s eye.

Tiffany Thayer was, among other things, a collector. He collected first issues of small magazines. He collected pamphlets. And, as the Canadian Theosophist said in a perfect capsule epitome of Thayer’s whole Fortean project: “The Fortean Society bids fair to become the greatest aggregation of Academic Cranks the world has known.” Three of those named by the Canadian Theosophist as evidence of Thayer’s plan are the subject of this posting: George Seldes, Norman Thomas, and Manly P. Hall. They all appeared in The Fortean Society Magazine or Doubt, with an MFS attached to their name—Member of the Fortean Society—but seemed inactive, unconcerned with Thayer or his aggregation of academic cranks. Indeed, they seem to have been more-or-less appointed to the Society because they were themselves academic cranks, and they continued their own work without much regard for the Society. They were Forteans in name only.

George Seldes was mentioned only once in the Fortean Society Magazine, issue 10 (Autumn 1944). But his publication, In Fact, was the apple of Thayer’s eye.

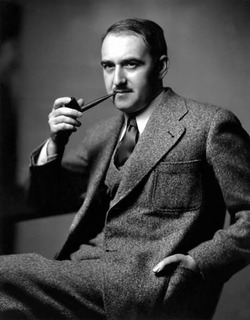

(Henry) George Seldes was born 16 November 1890 in New Jersey. His parents were Jewish émigrés from Russia. His brother, Gilbert Seldes, would grow up to be a writer. George would become a journalist. He worked for the Chicago Tribune through much of the 1920s, and so may have come into contact with some of the ur-Forteans such as Ben Hecht, Theodore Dreiser, Edgar Lee Masters, and even Thayer himself, who worked at a bookstore in Chicago during the early 1920s. Toward the end of the decade, Seldes, tired of fighting with the publisher, quit the Tribune to do freelance work. He published a series of books, some of them making use of material he had not been allowed to publish in the newspaper, and became a vociferous critic of the press and the role advertisers played in shaping news narratives.

In the mid-1930s, he became involved with another of the founding Forteans, J. David Stern, although their relationship was journalistic, not Fortean. In Witness to a Century, Seldes wrote,

“There was only one publisher in America who had a ‘chain’ of papers and who was a liberal: J. David Stern of the New York Post, Camden Courier and Camden Post. He fought Nazi fascism and therefore supported the Spanish Republic in July 1936. I had talked to him several times in previous years and once, when O.K. Bovard, editor of the nation’s best and most powerful liberal daily, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, was visiting me in New York, I telephoned Stern. He came to my apartment, and we spent the whole night in angry dispute over freedom of the press. As in all my previous battles with Stern over the silent and atrophied code of ethics of the profession, and the hope of a free press in the United States, Stern won this battle with Bovard and me as he won all others, with just this simple statement: ‘What do you want me to do, take a quixotic stand, print the truth about everything including bad medicine, impure food and crooked stock market offerings, and lose all my advertising contracts and go out of business--or make compromises with all the evil elements and continue to publish the best liberal newspaper possible under these compromising circumstances.’

“Mr. Stern compromised. He had to. He remained in business, and his newspapers were among the best published in the East.”

“Near the end of 1936 I asked Mr. Stern to send me to Madrid. He agreed to publish the reports my wife and I would send, but he offered no money to pay our way over. Nevertheless, one of the bravest episodes in American journalism of that decade was the publication by J. David Stern in his four daily newspapers of our twenty-four reports from Loyalist Spain, at a time other press lords were falsifying the news, publishing horrible stories of atrocities on the Loyalist side, suppressing the eyewitness accounts of officially ordered atrocities by the German Nazis, the Moors, Franco’s Foreign Legion--everyone on Franco’s side except his Italian troops.”

In 1940, Seldes started his own publication, In Fact, a four-page pamphlet that printed the news other papers could not, Seldes said. It was a liberal muckraking journal, attacking cigarettes as poisons, business lobbying groups, and the press, winning it attention from the FBI. The paper lasted ten years. Seldes had an evolving relationship with communism, starting out very close to the Communist Party’s stances but later staking out anti-Communist positions.

Thayer liked In Fact. In The Fortean 7 (June 1943, page 6) he wrote an column titled “Five Papers You Should Read”:

“All Forteans will find a great deal of interest in these five periodicals, all published in New York City:

The CALL (weekly) 303 Fourth Avenue $1.50 a year

IN FACT (weekly) 19 University Place $1.00 a year

BULLETIN (monthly) 317 East 34th St. $1.00 a year

TRUTH SEEKER (monthly) 38 Park Row $1.50 a year

CONSUMER’S COOPERATION 167 West 12th St. $1.00 a year

“Your Secretary regrets that he cannot steer you to an honest daily. He has tried to find one. How he has tried! . . . In this connection, if any Fortean knows of a readable daily newspaper being published today, he can do the Society, mankind, the world no greater service than to spread its fame far and wide. . . . What a commentary that is upon us as a people and upon this civilization that nowhere is a daily newspaper telling the truth today.”

Thayer mentioned In Fact again in Doubt 19 (Autumn 1947). That was the issue he devoted to flying saucers—but Thayer started his discourse on the disks from an odd place: critiquing the press, war-mongerers, and the public in “The United States of Dreamland.” In Fact was one of those papers trying to rouse the country from its slumber and awaken to truth, although Thayer did not entirely trust the weekly:

“The vast majority of us knew that Pearl Harbor was a put-up-job agreed to by the U.S. Government expressly to make the public ‘hysterical’ (only at that time the term was ‘war-minded’), but what could we--and what did we--do about it?

“Writing letters to editors doesn’t do any more good than writing them to Santa Claus. Nailing their lies doesn’t stop the chain-effect the lies have set in motion. No matter what percentage of the public is aware of a published falsehood, that awareness practically never gets into print, so that, say, 90% of the people in New York don’t know and can’t find out what 90% of the people in Chicago are thinking. Polls of ‘public opinion’ are engineered to substantiate any nefarious noxious nonsense the editors wish to foist upon us. The only publication of any potency which consistently exposes their frauds is IN FACT, a weekly, and IN FACT has an ax of its own to grind, and so circulates principally among groups which would like to control the United States of Dreamland, but never, never, never would permit the views of the masses to circulate freely. Nor does the limited potency of IN FACT stem the flood of falsehood in the slightest. On the contrary, each little exposure calls forth a smothering blanket of taller tales, so that the great stock of imposed hallucinations us weekly being squared to the seventh power.”

He eulogized In Fact’s passing in Doubt 32 (Spring 1951, page 73):

“The weekly, In Fact, was worth reading, until it folded recently. It exposed a great deal of rottenness, and if you can obtain access to back files, it is historically illuminating. The suspicion has been, however, that it was Communist-dominated, and the coincidence of its shutting up shop at exactly this time is probably significant.”

But Thayer’s most sustained discussion of In Fact, and the most revealing connections between Seldes and the Fortean Society, came in The Fortean Society Magazine 10, the only time Seldes’s name appeared in the magazine. Although it is true that Thayer was selling some of Seldes’s books—early on, the Fortean Society served as a clearinghouse for many books and made a meager allowance through their sale. The column which discussed Seldes was titled “Who is Our Friend?” He started by mentioning his earlier suggestion to read In Fact and The Call as well as—at another time LaFollette’s The Progressive and noted that Seldes was a “corresponding member,” which meant, theoretically, that he paid his dues of $2 per year and received each issue of Thayer’s publication. (In practice, many members never paid, but Thayer kept sending them the magazine.) Thomas was also a member, of a sort, but LaFollette was not. Thayer wrote,

“This note concerns the two Forteans, both of whom write books. The Society is happy to supply their books to any who may be interested. The writings of both men are professedly humanitarian by intention, but Your Secretary is forced to question their bona fides as such, at least as concerns George Seldes’ The Vatican ($2.50) and Norman Thomas’ What Is Our Destiny (no question mark).

“The Vatican ($2.50) was a selection of the CATHOLIC BOOK CLUB—no less. And Mr. Seldes has not so far replied to our question: ‘How in time could YOU write a book the Catholic Book Club would choose?’ If ever he does reply, the answer will be printed here.

…..

“While millions of men and women look to these two men, Seldes and Thomas, for LEADERSHIP—now if ever—they set up rival tootlings like twin pied pipers of Hamelin.

“What is our destiny—question mark—Mr. Thomas? The Vatican? Mr. Seldes?

“The most valuable service IN FACT has rendered humanity in the past three years was publication of an article exposing the ‘pulmotor’ as a murderous contrivance that destroys the possibility of recovery in a large percentage of the near-dead to whom it is applied . . . The publication’s blackest disservice to its own rank and file was one entire issue given over to white-washing George Gallup, the poll man. Be not deceived by that apology nor by any other of the many current attempts to restore these opinion-sampling agencies to the good graces of the public. Remember, this is Presidential year [sic], and the politicians need those straw-votes in their business. The low opinion you have held of all these vox-pop perverting influences is fully merited by every one of them. Don’t be seduced. Remember the Literary Digest!”

I am not sure what Thayer meant by the reference to the Literary Digest. But that fact that Seldes never bothered to respond to Thayer’s question—or, at least, Thayer never bothered to publish a response, if there was one—says about all that needs to be said on the topic of Seldes as a Fortean: he was an object of Fortean interest, loved for some of his stances, loathed for some of his failings, useful as a symbol of the Society’s dissension from the status quo, but not involved in the movement.

In the mid-1930s, he became involved with another of the founding Forteans, J. David Stern, although their relationship was journalistic, not Fortean. In Witness to a Century, Seldes wrote,

“There was only one publisher in America who had a ‘chain’ of papers and who was a liberal: J. David Stern of the New York Post, Camden Courier and Camden Post. He fought Nazi fascism and therefore supported the Spanish Republic in July 1936. I had talked to him several times in previous years and once, when O.K. Bovard, editor of the nation’s best and most powerful liberal daily, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, was visiting me in New York, I telephoned Stern. He came to my apartment, and we spent the whole night in angry dispute over freedom of the press. As in all my previous battles with Stern over the silent and atrophied code of ethics of the profession, and the hope of a free press in the United States, Stern won this battle with Bovard and me as he won all others, with just this simple statement: ‘What do you want me to do, take a quixotic stand, print the truth about everything including bad medicine, impure food and crooked stock market offerings, and lose all my advertising contracts and go out of business--or make compromises with all the evil elements and continue to publish the best liberal newspaper possible under these compromising circumstances.’

“Mr. Stern compromised. He had to. He remained in business, and his newspapers were among the best published in the East.”

“Near the end of 1936 I asked Mr. Stern to send me to Madrid. He agreed to publish the reports my wife and I would send, but he offered no money to pay our way over. Nevertheless, one of the bravest episodes in American journalism of that decade was the publication by J. David Stern in his four daily newspapers of our twenty-four reports from Loyalist Spain, at a time other press lords were falsifying the news, publishing horrible stories of atrocities on the Loyalist side, suppressing the eyewitness accounts of officially ordered atrocities by the German Nazis, the Moors, Franco’s Foreign Legion--everyone on Franco’s side except his Italian troops.”

In 1940, Seldes started his own publication, In Fact, a four-page pamphlet that printed the news other papers could not, Seldes said. It was a liberal muckraking journal, attacking cigarettes as poisons, business lobbying groups, and the press, winning it attention from the FBI. The paper lasted ten years. Seldes had an evolving relationship with communism, starting out very close to the Communist Party’s stances but later staking out anti-Communist positions.

Thayer liked In Fact. In The Fortean 7 (June 1943, page 6) he wrote an column titled “Five Papers You Should Read”:

“All Forteans will find a great deal of interest in these five periodicals, all published in New York City:

The CALL (weekly) 303 Fourth Avenue $1.50 a year

IN FACT (weekly) 19 University Place $1.00 a year

BULLETIN (monthly) 317 East 34th St. $1.00 a year

TRUTH SEEKER (monthly) 38 Park Row $1.50 a year

CONSUMER’S COOPERATION 167 West 12th St. $1.00 a year

“Your Secretary regrets that he cannot steer you to an honest daily. He has tried to find one. How he has tried! . . . In this connection, if any Fortean knows of a readable daily newspaper being published today, he can do the Society, mankind, the world no greater service than to spread its fame far and wide. . . . What a commentary that is upon us as a people and upon this civilization that nowhere is a daily newspaper telling the truth today.”

Thayer mentioned In Fact again in Doubt 19 (Autumn 1947). That was the issue he devoted to flying saucers—but Thayer started his discourse on the disks from an odd place: critiquing the press, war-mongerers, and the public in “The United States of Dreamland.” In Fact was one of those papers trying to rouse the country from its slumber and awaken to truth, although Thayer did not entirely trust the weekly:

“The vast majority of us knew that Pearl Harbor was a put-up-job agreed to by the U.S. Government expressly to make the public ‘hysterical’ (only at that time the term was ‘war-minded’), but what could we--and what did we--do about it?

“Writing letters to editors doesn’t do any more good than writing them to Santa Claus. Nailing their lies doesn’t stop the chain-effect the lies have set in motion. No matter what percentage of the public is aware of a published falsehood, that awareness practically never gets into print, so that, say, 90% of the people in New York don’t know and can’t find out what 90% of the people in Chicago are thinking. Polls of ‘public opinion’ are engineered to substantiate any nefarious noxious nonsense the editors wish to foist upon us. The only publication of any potency which consistently exposes their frauds is IN FACT, a weekly, and IN FACT has an ax of its own to grind, and so circulates principally among groups which would like to control the United States of Dreamland, but never, never, never would permit the views of the masses to circulate freely. Nor does the limited potency of IN FACT stem the flood of falsehood in the slightest. On the contrary, each little exposure calls forth a smothering blanket of taller tales, so that the great stock of imposed hallucinations us weekly being squared to the seventh power.”

He eulogized In Fact’s passing in Doubt 32 (Spring 1951, page 73):

“The weekly, In Fact, was worth reading, until it folded recently. It exposed a great deal of rottenness, and if you can obtain access to back files, it is historically illuminating. The suspicion has been, however, that it was Communist-dominated, and the coincidence of its shutting up shop at exactly this time is probably significant.”

But Thayer’s most sustained discussion of In Fact, and the most revealing connections between Seldes and the Fortean Society, came in The Fortean Society Magazine 10, the only time Seldes’s name appeared in the magazine. Although it is true that Thayer was selling some of Seldes’s books—early on, the Fortean Society served as a clearinghouse for many books and made a meager allowance through their sale. The column which discussed Seldes was titled “Who is Our Friend?” He started by mentioning his earlier suggestion to read In Fact and The Call as well as—at another time LaFollette’s The Progressive and noted that Seldes was a “corresponding member,” which meant, theoretically, that he paid his dues of $2 per year and received each issue of Thayer’s publication. (In practice, many members never paid, but Thayer kept sending them the magazine.) Thomas was also a member, of a sort, but LaFollette was not. Thayer wrote,

“This note concerns the two Forteans, both of whom write books. The Society is happy to supply their books to any who may be interested. The writings of both men are professedly humanitarian by intention, but Your Secretary is forced to question their bona fides as such, at least as concerns George Seldes’ The Vatican ($2.50) and Norman Thomas’ What Is Our Destiny (no question mark).

“The Vatican ($2.50) was a selection of the CATHOLIC BOOK CLUB—no less. And Mr. Seldes has not so far replied to our question: ‘How in time could YOU write a book the Catholic Book Club would choose?’ If ever he does reply, the answer will be printed here.

…..

“While millions of men and women look to these two men, Seldes and Thomas, for LEADERSHIP—now if ever—they set up rival tootlings like twin pied pipers of Hamelin.

“What is our destiny—question mark—Mr. Thomas? The Vatican? Mr. Seldes?

“The most valuable service IN FACT has rendered humanity in the past three years was publication of an article exposing the ‘pulmotor’ as a murderous contrivance that destroys the possibility of recovery in a large percentage of the near-dead to whom it is applied . . . The publication’s blackest disservice to its own rank and file was one entire issue given over to white-washing George Gallup, the poll man. Be not deceived by that apology nor by any other of the many current attempts to restore these opinion-sampling agencies to the good graces of the public. Remember, this is Presidential year [sic], and the politicians need those straw-votes in their business. The low opinion you have held of all these vox-pop perverting influences is fully merited by every one of them. Don’t be seduced. Remember the Literary Digest!”

I am not sure what Thayer meant by the reference to the Literary Digest. But that fact that Seldes never bothered to respond to Thayer’s question—or, at least, Thayer never bothered to publish a response, if there was one—says about all that needs to be said on the topic of Seldes as a Fortean: he was an object of Fortean interest, loved for some of his stances, loathed for some of his failings, useful as a symbol of the Society’s dissension from the status quo, but not involved in the movement.