A fragmentary history of an active, married Fortean couple.

As best as I can figure, Hilda Virginia Downing was born 14 October 1909 in Ohio to Robert Epkey Downing and Edith E. Ganoe. She was the fifth child, preceded by two brothers and two sisters. Robert was a pumper in an oil field. Two more sons followed by 1920, and the family also took on a cook and a nurse. At the time, Robert was still in the oil industry and owned his home free and clear. The eldest son, Robert, was the only other one in the family to officially work. He was a clerk at a bank.

Almost six years after the birth of Hilda, George Christian Bump came into this world—again, as best as I can determine. He was born 21 July 1915 in California, the only child of Sumner and Margaret Bump. Sumner was a sawmill superintendent at the Hilt Lumber Mill Company in Siskiyou county, far in the northwest of the state. Both the Bump parents had been born in Iowa. They rented their house, presumably from the mill itself.

As best as I can figure, Hilda Virginia Downing was born 14 October 1909 in Ohio to Robert Epkey Downing and Edith E. Ganoe. She was the fifth child, preceded by two brothers and two sisters. Robert was a pumper in an oil field. Two more sons followed by 1920, and the family also took on a cook and a nurse. At the time, Robert was still in the oil industry and owned his home free and clear. The eldest son, Robert, was the only other one in the family to officially work. He was a clerk at a bank.

Almost six years after the birth of Hilda, George Christian Bump came into this world—again, as best as I can determine. He was born 21 July 1915 in California, the only child of Sumner and Margaret Bump. Sumner was a sawmill superintendent at the Hilt Lumber Mill Company in Siskiyou county, far in the northwest of the state. Both the Bump parents had been born in Iowa. They rented their house, presumably from the mill itself.

The 1930 census has no record for the Bumps, which isn’t entirely surprising given the small communities in which they lived. No later than 1935—and possibly much earlier— the family had relocated to Loyalton, deep in the Sierras, and then, between 1935 and 1940, to Burlingame, California, a southern suburb of San Francisco. Both of his parents were very active in the community, especially in conservation, and also the church. By that point, George had been joined by two sisters, Margaret and Betty. While in Burlingame, Sumner continued working in the mining industry and George attended school, as did his sisters. They would have been in high school or just starting college; George was doing some kind of post-graduate work: according to The Lumberman (vol. 64, 1937) he was a recent graduate of the University of Nevada at Reno. The University has him finishing a BS in the college of arts and sciences that May. I find no record of George Bump during World War II.

Meanwhile, the Downings had moved to Tulsa, Oklahoma, where Robert was running an oil company. Hilda was the eldest of the children still living at home. (There was also a housekeeper, only a few years older than her.) Officially, the census listed Hilda as unemployed, but she was doing some writing—a review of Edna Ferber’s Oklahoma novel Cimmaron had appeared under her byline in a 1929 issue of the Tulsa Tribune. She attended the University of Tulsa in the late 1930s—it looks like her third year was 1939 or 1940—where she continued writing, as a reporter for the yearbook, if not also the newspaper.

At some point in the 1940s, George and Hilda made their individual ways to Chicago, where they met—and wed. That information comes from Doubt, and while I have no particular reason not to believe it, I also cannot find a record of the marriage, despite Cook county having excellent marriage records. Thayer announced the joining in Doubt 14 (Spring 1946): “Two esteemed members of opposing sexes, Hilda Downing and George Christian Bump, both of Chicago, wed. This is the first Fortean marriage on record as such. The Bride’s friends gave her a shower of frogs.” A December 1946 article in the San Mateo Times does mention that Bump had a wife, but it does not give her name—proof yet again that women at this time were often Fortean objects themselves, damned and forgotten by the public at large.

I’m not sure what Bump was doing for work at the time; Thayer listed Hilda as a writer, and there is some scant evidence in support of that. She has a couple of mentions in Inland Printer American Lithographer from around this time, one as Hilda Bump, another as Hilda Downing Bump. These were articles on Ray DaBoll, a calligrapher, and Kenneth Butler, of the Wayside Press. If she published other articles, I have not been able to find them under the many possible variations of her name.

The exact sequence—and, indeed, nature—of events over the next decade or so are hard to arrange definitively from the fragments that exist. It seems that sometime around 1960 the Bumps divorced, or at least separated. An issue of Inland Printer from that year has a want-ad from her—name Hilda Downing Bump—requesting editorial or proofreading work in the Kansas City area. At the same time, George was in California getting an MS in mathematics from Stanford University. Subsequently, there appears a Hilda Downing doing library work in Missouri, first a high school librarian, later president of the Missouri Association of School Libraries, and eventually library supervisor at the State Department of Education. It may not be the same person, though, as in at least one case the middle initial is given as G. However, everything else lines up, including the dates. Downing’s name stopped appearing in the Missouri Library Association publications in 1968, and the social security death index lists Hilda Downing as dying December 1968 in Kansas City Missouri. She was 59.

On 8 May 1960, in Santa Clara, California, George C. Bump married Liselott A. Weidenkopf. He was 44. She was 29. I know nothing of her background. I believe that they had five children, all in California, all surnamed Bump. I do not know Bump’s occupation—but his avocation seems to have been writing. He had a philosophy of life which he wanted to elucidate and he did so in what seems to have been extensive correspondence, although only fragments remain—at least, that’s all I have found.

As best I can tell, Bump’s correspondence began in the mid- to late-1940s, after he had married Hilda and when they were living in Chicago. He was in correspondence with the Fortean Society, of course, as well as the magazine The Humanist, which was weakly allied with the Fortean Society through its editor, Edwin H. Wilson, and some shared members. He was also in contact with Thayer himself and Eric Frank Russell. In addition, he wrote to the socialist journal The Word, the anarchist The individualist and the Irish paper The Leader, and other writers including—but probably not limited to—Rudolf Rocker and Frank Chodorov. He appeared in the letter column of The Chicago Tribune. Much later, letters would go to The New American Mercury, the Oxnard Press Courier, the California Board of Equalization, and the Stanford Daily. Together, the letters show the continuity of his thought over the years as well as some dramatic turnabouts.

In the most blunt terms, George Christian Bump of the 1940s was an egoist, a radical individualist. He considered himself something of an anarchist. There were many others associated with Fort with a similar bent—Benjamin de Casseres, for example, held similarly radical egoist views, as far as I can tell, but Bump’s anarchism ran rightwards, different than many—not all!—of the Forteans, who tended toward a left-libertarianism. Nonetheless, he could appreciate the socialist magazine The Word because, as he said, “I do not accept the economic (Marxian) interpretation of history. I believe that history is created by a force of character. But I am convinced that ‘The Word’ is on my side in the battle because it is radical and whatever is truly radical expresses truth.” The battle he mentions—that was the battle between the individual and society.

Bump laid out his ideas in a series of letters to Eric Frank Russell—internal evidence suggests that there may have been a dozen or more, of which only two survive. One dated 30 November 1947, though digressive, maybe bests summarizes his thought; at least, it seems in accord with what he wrote elsewhere, but also more expansive, even if not closely argued. The relevant excerpts:

“The way I figure it, anarchism means ‘Live and let live.’ State-ism is the policy of the dog in the manger.

“I think the principle of leadership, that is, feudalism, is inherent in Nature. But out of this there has grown a certain form of perversion, disease, and parasitism known as the court. The court grows up originally around some outstanding man and consists to begin with of his wives, aides, and hangers-on. When this man dies, the court assumes control, choosing another individual to replace him.

“It would be hard to say at just what point the system becomes perverted. But at any rate, all the courts existing now are depraved; and so I say arbitrarily that all Nationalism is depravity and perversion.

“I maintain that we shd deal with each other as one individual to another rather than thru the court. In other words, I advocate feudal (man to man) relations rather than relations of masses to masses.

“Out of court there develops the system of church and state, ruled ostensibly by Parliament but actually by a secret priesthood. There may be good men in Parliament but the system of Parliamentism itself serves to maintain the rule of a degenerate and depraved priesthood.

“We are apt to dismiss the Church as unimportant becuz we think it has little power. But the church, like the royal family, forms a necessary part of the system. It is a pattern, a complex, called in the Bible ‘Satan’ or the ‘Whore’. I call it the great vampire.

“Local autonomy is a step in the direction of anarchy. As reported in ‘Freedom’, one of the anarchist leaders during the civil war in Spain advocated local autonomy as a step toward anarchy.

…….

“By heritage and natural affinity I belong to the [Irish] Dissenters. The Dissenters are of an individualistic tendency and are inclined to regard the Roman and Anglican Church as out of the same pattern. The Dissenters are to some extent opposed to the system of Court-State-Church in principle. In a way I am merely an extreme Dissenter.

“You may say, ;Why be a Dissenter? Why not just ignore the church?’ I do ignore the Church in that I do not try to change the personal opinions of the church-goer. But I think something can be accomplished by calling the attention of those who are actually Dissenters to the nature of Church and State.

“The way I look at it, Jesus was not a god anymore than anyone else is but a man, a man opposed to the system of church and state. Jesus clearly stated that he was a god only in the sense that we are all gods (that is, immortals). The priests killed him becuz he was undermining their system.

“The story of Jesus has been added to by various individuals, many of them with the old priestly preconceptions. But the naked outline of the story stands out in all clarity. Jesus was a great spiritual leader. The priests made him a god so that they could utilize his memory for their own purposes.

“It is always man versus God. God is a function of priestcraft, something degenerate and depraved. A true man is infinitely superior to any god.

“The ‘whore’ has always ruled England thru the court. At the time of Queen Elizabeth, the court was dominated by agents of Spain and the pope. With slight variations, Satan still controls England as every other country in the same way.

………

“I have often thot of writing a story (or many stories) on the future of mankind, involving the development of new nations of many kinds (feudal, democratic, theocratic, etc.). I am sure I could write fascinating (to me) stories. But I have too many other thinggs to do. I cd exemplify my principles of local autonomy by letting small nations and individuals (in my stories) defeat the world-state. The more I think about it, the more I like the idea. Even if my stories are never publisht, I wd get great satisfaction out of seeing the world-state and its agents defeated, even in a story.”

Elements of this philosophy appeared in Bump’s various other missives from the late 1940s. His letter to The Humanist, for example, posited the eternal struggle between individual and the state. An October letter to the Chicago Tribune used the then-dominant historical position that the American Civil War was fought over state’s rights to wish that “The Confederacy should have won the war. If the principle of states’ rights had been upheld, we probably never would have had the financial tyranny of the federal reserve system, the destruction of individual spirit and our economic well being thru the income tax, or the subservience of the United States to English policy in the last two World wars. Tho they were defeated in battle, to the Confederacy still belongs the victory for the eternally right: it is only a question of time until this is recognized by everyone.” An earlier letter to the same paper—from June—was similarly anti-English: in regards to the Jews and Arabs battling over Palestine, the real answer, for Bump, was “for the English to get out and let the Jews and the Arabs settle the matter among themselves.” (No doubt these prejudices irritated Russell.)

Of course, these themes were often reflected in his correspondence with the Fortean Society. Indeed, his individualist philosophy informed his reading of Charles Fort.

Exactly when George and Hilda joined the Fortean Society is impossible to say—just as I cannot say when they first read Fort or why they were attracted to the Fortean Society. Their first connection to Fort that I can find is Thayer’s mention of their marriage in the pages of Doubt. He calls them esteemed members, and they may have been, but neither of their names appear in Doubt before that, and I can find no mention of Fort in any of their writings from before that time, either. Indeed, Downing’s name would appear only once more in Doubt, and that in association with her husband, raising the question of whether she had any interest in Fort at all. (One might say that her time classifying library books was something of a Fortean endeavor, but I have no evidence that she made the connection.) That second—and final—mention of Hilda Downing came in Doubt 24 (1949), and was part of an announcement of several Fortean marriages—the Bumps, the Drussais, the Youds, and The Gaddisses. The article included a picture of each of the couples.

George, on the contrary, was active in the Society. At the time, the Society was experimenting with chapters—local Fortean Societies. Chicago was the second city to form one (making it Chapter 3, in Fortean fashion, Thayer’s operation having the honor of being Chapter 1), and Bump was among those involved—local autonomy, right? Thayer wrote in April 1949, “No general meeting has been held, principally from lack of a hall, but members Castillo, Bump, Brady, Hurd and others are in organizational conferences pretty much all the time. The explosive potential is enormously greater than anything Lillienthal dreams of--what with provivisectionist ‘Ajax’ Carlson, anti-vaccinist Hurd, rocketeer Farnsworth and pro-Kantian Brady all wrestling in the same cyclotron.” Supposedly, Bump was giving lectures in Chicago at the time, and he incorporated Fort and his books into the talks. Otherwise, he contributed to Doubt more than a dozen times, some of those contributions substantial, and related to his interest in individualism.

Bump had the typical Forteans fascination with anomalies, but these often carried political overtones—when they weren’t directly matters of politics and philosophy. His correspondence with Eric Frank Russell showed a similar inclination—notes on a man said to live to 152, the superior vascular system of ‘negroes’, the increasing population of Arab countries, prejudice against a fortune-teller by the police, the declining buying power of the average worker, oddities surrounding the Lincoln assassination, the tendency of Catholics, Democrats, and socialists to disdain individuality, the Encyclopedia Britannica article on civil liberties, the tendency of mainstream press to ignore developments in the Arab world, including French colonialism—a Fortean damned fact, but of a very political bent.

Perhaps the most strictly non-political was the material he sent in on flying saucers and the fire-starting girl of Macomb, Illinois—but since Thayer credited him generally, alongside many others, it is hard to know what Bump thought of those phenomena; indeed, many of the credits Thayer gave to Bump were generic and not correlated to specific reports. There were enough, though, to show that Bump had a healthy skepticism for authority. He sent in a story about a woman who was supposedly so allergic to anesthesia that she exploded on the operating table, for instance, and he seems to have been suspicious of the fluoridation of water, like Thayer. In 1952, he told Thayer the story of attending a Christian church where the proposal was put forth that members should not sue each other—and it did not pass, which prompted Bump to leave. Thayer thought the idea good, and wanted to one-up the Christians, so suggested Forteans adopt the practice. (Nothing seems to have come of the matter.)

Thayer did not seem to appreciate Bump very much—which wasn’t uncommon. He disdained a number of Forteans. And even friends could find Thayer tiresome and tedious. One gets the sense that Thayer was very alone, except for his wife. In April 1948, he chided Russell for indulging Bump with any attention: “You are a sucker to answer Bump. He picks on you because I bush him off. Don’t do it.” Which suggests that there was at least a one-sided correspondence between Bump and Thayer, although none of it seems to have survived. Probably, like others of Thayer’s Fortean correspondents he simply tired of not getting answers and so just sent in material. He did that until the mid-1950s.

Despite Thayer’s dismissal of Bump, he gave him a lot of space in Doubt—not just with the credits and small reports, but with recommended readings and short essays. (Bump had provided Russell with the same in correspondence, recommending books and including harangues.) In particular, Bump had occasion to publish lengthy (for Doubt) pieces in issues 25, 26, and 37—that last being 1952. These were largely amplifications of the philosophy that he had laid out in his letters to Russell—and elsewhere—with recommendations that Forteans read certain books. These three—let’s call them essays—demonstrate that Bump, like Thayer, was skeptical of modern society and government, and let that skepticism influence how he read and understood Fort—which is not to say that there is one right way to read Fort, but that Bump and Thayer had an overlapping (but not congruent) political interpretation of Fort and Forteanism.

The first essay, appearing early in 1949, most clearly showed Bump’s political view of Forteanism. He started by recommending Frank Chodorov’s book The Myth of the Post Office. Bump had earlier recommended Chodorov to Russell; he liked his anarchism, but recoiled at his leftist sympathies, he told Russell, and made a similar point in Doubt: “Chodorov is intent (like Nock) on attacking the ‘State’, which I identify in principle with the ‘Orthodoxy’ which Fort and Forteanism attack. Chodorov claims to be advocating ‘social power’ as against the power of the ‘State.’ But actually and by logical necessity he is advocating freedom of ‘private enterprise’ to operate and grow.

“Fort in opposing orthodoxy is also advocating freedom of enterprise altho he makes reference to it only rarely, as on page 588 of The Books where he says: Resistance to notions in this book will come from persons who identify industrial science, and the good of it, with the pure, or academic sciences that are living on the repute of industrial science.

“The basic conflict is between growth and reaction, between those who want to grow and want sufficient ‘freedom of enterprise’ in order to grow and those who cannot or will not grow and therefore can only act as resistance to growth, as mass, inertia, reaction.

“The resistance to growth is partly human and partly non-human, hidden, esoteric, occult. It tries to keep hidden because to the extent it is understood, it loses power.

“To the extent that an individual is ‘de-horned’ and loses his power to fight effectively against the hidden control, he is sanctified and blessed and becomes a part of orthodoxy, a mere puppet of the hidden control.

“The official advocates of both ‘free enterprise’ and its theoretical opposition, socialism, are zombies, mindless agents of the hidden control. They are always united in opposing any real freedom for growth.

“The purpose of their sham battle is to distract attention from the real war, which is between growth and resistance to growth, and the inevitable result of which is the gradual victory of growth.”

This reading of Fort is unusual, although credible—to an extent. As Bump himself admits, Fort rarely discussed economic matters, and certainly made no brief for free enterprise. (One could only assume that he would have mocked the notion of an invisible hand guiding capitalist development, as the image is so absurd.) The quote from Fort comes amid a more general discussion of how science has come to get to much credit for civilization, and Fort needed to acknowledge that some science, indeed, had helped humanity, but of a limited, qualified kind—what others, including Thayer, would call technology. At no point does Fort associate this science with capitalism, but Bump’s reading is not ruled out by what Fort says—it’s just an extension, suggesting that Bump’s real interest was never really Fort but political and economic philosophy. Admittedly, though, that he could quote a small fragment from the Books (Lo!, as it happens) shows he had read Fort carefully.

The next issue of Doubt had Bump bringing a most obscure tome to the attention of Forteans—an 1853 book by the polymathic Charles W. Webber (journalist, explorer, medicine man, theologian) called “‘Spiritual Vampirism: The History of Etherial Softdown and her Friends of the “New Light”’. As Bump glossed it, the book claimed that vampires were real, although they fed not on blood, but a spiritual energy called the Odic fluid: the active principle of life, something like the body’s own subtle electricity, which connects the materials and spiritual worlds—is, indeed, the only means of communication between the two. According to Webber—who was wary of revealing too much—great leaders had an excess of Odic fluid, which they could use to fill their followers. Others were deficient, their nervous systems out of whack, and they need to feed on the Odic fluid of others. These were parasites. These are vampires.

Bump concluded by connecting Webber’s theories to the suppositions of Fort—Webber, he insisted, was telling a true story: the book “describes reality. This book tells in factual detail what the writers of horror fiction only hint at.” So then where are the vampires? They form hidden cults. “Vampirism must be organized in some way to keep mankind in ignorance. This would explain the campaign to ridicule against the study of psychic phenomena. For to the extent that these things are understood it becomes difficult for vampires to practice their arts. If, as Fort hazarded, we are owned and exploited by a hidden entity, these ‘human vampires’ may act as media by which the vitality of the human race is drained off to support the life of the supreme vampire which holds humanity in thralldom.”

The theory represented a fairly paranoid view of history—not inconsistent with other Fortean ideas, at that. Paranoia was common among Forteans. The question that Bump’s ideas immediately raises, of course, is who are these vampires? If we go by his 1947 letter to Russell—the church was a vampire. The state, in its way, too. One is tempted to say—as Bump was drawn to synthesizing all forces into two polar sides—the vampires are the orthodox themselves. (Incidentally, the horror writer Dan Simmons wrote a book on this theme many years later, the much-too-long Carrion Comfort). Again, for Bump, Forteanism helps explain politics and economics more than it does science.

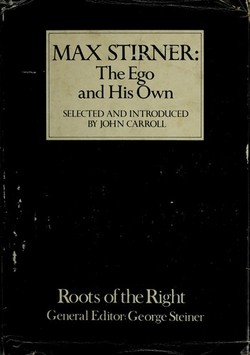

The third essay concerned Max Stirner and his book—translated into English as The Ego and Its Own, which was of interest to a number of Forteans, including Thayer, its rarity bedeviling those who wanted to develop their ideas about anarchism. Bump wrote, “I think that all Forteans should read Max Stirner’s ‘The Ego and His Own.’ Stirner clearly shows the fundamental falseness of Orthodoxy and therewith the means to overthrow it. Orthodoxy assumes (and must assume) that Universals are the true Reality. But Stirner pointed out that the Real is the Particular, not the Universal. The reality of each individual lies in his Uniqueness, not in his partaking of universal qualities. Thus an individual may be a man and an American. But he is more than that--he is himself!

“As I see it, all conflicts are related to conflicts of thought and the fundamental conflict of thought is between realists and escapists, what William James called the tough-minded and the tenderminded, The realist tries to deal effectively with reality; the escapist tries to escape from reality.

“Please don’t misunderstand me. I am not saying that it is the only conflict. I am merely saying that it is the most fundamental conflict. I think that war is inherent in life but that the destructiveness of war is minimized by realism.

“To some extend [sic] we all try to escape from reality (the outer reality) in order to preserve our individuality. This represents in some degree a war with reality. The difference between the realist and the escapist lies in this, that the realist always recognizes that the outer reality is there while the escapist tries to convince himself of its non-existence.

“Universalism is the manifestation of escapism. The escapist finds the actual world too disagreeable to face; so he tries to replace it by a world of universals, that is, ‘heaven.’

“The realist carries on personal wars as he has to in order to maintain his existence in this world. But the universalist is engaged in a war against reality itself. He is at war with ‘this world.’

The escapist (universalist) comes into contact with reality in great part through contact with realists. Hence his war against reality takes the form of a war against realists.

“Stirner thinks that all feelings (as affection, etc.) are manifestations of egotism, that (for example) an individual likes to see another individual happy because this in turn brings him pleasure. With this I do not entirely agree. I think that every emotion, every passion, has a certain autonomy, a life of its own. In proper development, all the emotions, including egotism, are in harmony. But it is possible to convert certain emotional tendencies into anti-egotism, to turn the individual against himself.

“Nietzsche describes how this is done by Christianity. We hear a lot now about schizophrenia (split personality). Is it not possible that all schizophrenia is the product of Christianity or its derivatives?

“The diversion of the passions so as to turn the individual against himself is of course the work of the escapists (universalists). It might be said that universalism is a self-created disease while schizophrenia is a disease imposed upon one by others. Perhaps the two diseases are to be found together in the same person.

“The universalist thinks that he is escaping from ‘this world’ into freedom. But actually he is imprisoning himself. He bounds himself on all sides with rituals and dogmas so as to keep out the icy breath of reality.

“Always gnawing at the vitals of the escapist is the fear of reality resulting from the subconscious knowledge that he has not overcome reality but only escaped from it temporarily. He is always in need of assurance that he is right. So he seeks ‘converts.’ He can maintain his illusional world only by the constant reiteration that it is the real world. This is called ‘prayer.’ He has ‘faith’ that he has overcome the real world. But in his heart of hearts he knows that it is not so. To still this inner voice he congregates with others in ‘churches,’ thinking by the power of numbers to establish the supremacy of faith over reality. But ultimately it is all in vain.

“Growth, expanson [sic], is the tendency of all life, even of the perverted and diseased life. So the illusionist, the escapist, seeks to spread the boundaries of his ‘Church.’ But what to him is freedom from reality is to the realist only imprisonment from reality. Hence the continual revolt by ‘individualists’ against the dogmatism of the Church and its derivatives, ‘modern science,’ the priesthood of medicine, etc.

“In the cult of ‘modernism,’ the doctor has taken the place of the priest. The ‘selfless’ labors of the doctors to deliver people from the consequences of thir [sic] follies by ever-new forms of magic, none of which ultimately succeed in their purpose, is the vicarious atonement over again. The phrase ‘men in white’ suggests the sacredness of the temple. Universalists always prefer the colors black and white because of their ‘abstract’ quality, their conveying of the quality of ‘not being in this world.’

“To me Forteanism represents the revolt of the realists (the ‘individualists’) against the church of modern science and the ‘men in white’ (the new church which has been erected with the dogmas of science as a foundation in an attempt to preserve the illusional world of the escapists against harsh reality).”

Bump’s thoughts on Stirner are perhaps the most revealing of Forteanism more generally at the time—not that there weren’t many varieties of Forteanism, for there were, but that they often shared a central core. This core was the focus on the individual—anomalous events are individualistic by definition. Science, at the time, and society more generally, were tending toward the statistical. Forteans stood against this trend, particulars in a statistical universe. In this case, then, Bump’s political reading of Fort, although idiosyncratic in many ways, got at a common anxiety among the Forteans, that the world was erasing them, turning them into naught but a number.

Bump last appeared in a 1958 issue of Doubt, but that material may have been saved from an earlier submission. Certainly, the Fortean Society was almost at its end, going out of business in 1959. But The timing makes sense with his life circumstances—it was around this time that he seems to have divorced Hilda, went back to California, remarried, and received a degree from Stanford. Forteanism certainly could have been squeezed out by those events. Further suggesting that it was a change in Bump, and not the loss of the Society, that altered his Forteanism, I find no record of him discussing Fort in the years after the 1950s, nor do I find him associated with later Fortean organizations, which tried to pick up from Thayer and recreate his mailing list. It is not definite, but given Bump’s various interests, it is likely that he would have heard from the International Fortean Organization that formed in the 1960s, but, if he did, he stayed aloof from it.

He did not stay his letter-writing hand, though, and these show that politics continued to consume him, some of his ideas remaining the same, others changing dramatically—at least based on the evidence available. He wrote into the new American Mercury, which had taken a hard-right since its early days under Mencken, arguing that people should be allowed to have as many children as they wanted and warning about the dangers posed by Cuba. He also sent in material to a southern California newspaper—that was where he was living at the time, southern California. Probably, there are more examples of his correspondence that I have not found.

In the late 1960s, and through the 1970s, he became legally entangled with California’s Board of Equalization—which collected taxes. Bump and his wife, it seems, refused to pay taxes and filled out their forms in unorthodox ways—writing “object” on the blanks in at least one case. The Board, using bureaucratese, explained Bump’s argument: “In his petition, amendment to petition, motion for summary judgment and other documents filed with the Court, petitioner alleges that he received no amount in dollars during the years here involved since the only legal dollars are gold and silver or certificates redeemable in gold and silver, and that his rights under the 5th, 7th, 8th and 9th Amendments to the Constitution have been violated by depriving him of property without due process of law, depriving him of the right to trial by jury, inflicting cruel and unusual punishment upon him and depriving him of services by public servants who have taken an oath of office to defend the Constitution of the United States.”

The most surprising turn of events was recorded in the Stanford Daily. A 1979 letter from Bump castigated homosexuals—“Are there any individuals or groups at Stanford who regard homosexuality with abhorrence and who resent the attempt to ‘brainwash’ them into accepting homosexuality and treating gays with ‘sensitivity,’” he wanted to know, because it was obvious to him “every sane human being regards homosexuality with instinctive abhorrence.” This stance against gays cut against his individualism; more interesting, though, was he cited the Bible in support of his position. That this wasn’t a historical but a theological point was made clear in another letter, this one from 1981. Americans had to accept biological limits, he said—again going against his previous individualism—biology dictating that women could not be measured against men and that there were heritable differences between the races. (So much for no universals!) He then went on to complain that feminism, the sexual revolution, and abortion—which was the immediate cause of the missive—resulted from a loss of religious instruction.

It is hard to imagine that the arch-egoist, the man who called the state a vampire and the church a whore could pen the following words, but he did. Conservative he remained, skeptical of the government he remained, but no longer was he anxious about the influence of the church, no longer did he think nationalism and the state against nature, no longer did he set the individual against universals: he embraced the universal, in just the way he had castigated Democrats, socialists, and Catholics of doing so many years ago: “Some individuals may succeed in living virtuous lives without being associated with any institutionalized religion; but collectively mankind cannot survive without religion. The human race is inherently religious; and no nation has ever existed or can exist without religion. (The socialist anti-religious so-called nations are parasitic entities which will perish when we stop giving them aid and support.) America is a Christian nation and people; and when we cease to be Christian, we shall cease to be either a nation or a people. Christianity is based on the Bible; and the Bible condemns infanticide above all other crimes. It provides the death penalty for causing abortion.”

It would be fascinating to know exactly how Bump’s views changed over those thirty-five years, his right-leaning respect for free enterprise and disdain for socialism coming to support not individuality and egoism any longer, but rather the very things that he once claimed to hate most of all. And it would be interesting, too, to know if Forteanism played any role in this evolution, although that does seem doubtful—not because it is impossible to have a strongly conservative Christian reading of Fort, but more banally because he seems to have lost interest in the Bronx philosopher.

As best I can tell, Bump lived in southern California during the mid-1980s, at least, moving, perhaps, from Moorpark California to Thousand Oaks. (The Ronald Reagan Presidential Library is sited between those two cities.) He lived a long life, passing away in 2013 at the age of 98. At the time, he was in Longmont, Colorado. A short obituary I found gave only his birth and death dates.

Meanwhile, the Downings had moved to Tulsa, Oklahoma, where Robert was running an oil company. Hilda was the eldest of the children still living at home. (There was also a housekeeper, only a few years older than her.) Officially, the census listed Hilda as unemployed, but she was doing some writing—a review of Edna Ferber’s Oklahoma novel Cimmaron had appeared under her byline in a 1929 issue of the Tulsa Tribune. She attended the University of Tulsa in the late 1930s—it looks like her third year was 1939 or 1940—where she continued writing, as a reporter for the yearbook, if not also the newspaper.

At some point in the 1940s, George and Hilda made their individual ways to Chicago, where they met—and wed. That information comes from Doubt, and while I have no particular reason not to believe it, I also cannot find a record of the marriage, despite Cook county having excellent marriage records. Thayer announced the joining in Doubt 14 (Spring 1946): “Two esteemed members of opposing sexes, Hilda Downing and George Christian Bump, both of Chicago, wed. This is the first Fortean marriage on record as such. The Bride’s friends gave her a shower of frogs.” A December 1946 article in the San Mateo Times does mention that Bump had a wife, but it does not give her name—proof yet again that women at this time were often Fortean objects themselves, damned and forgotten by the public at large.

I’m not sure what Bump was doing for work at the time; Thayer listed Hilda as a writer, and there is some scant evidence in support of that. She has a couple of mentions in Inland Printer American Lithographer from around this time, one as Hilda Bump, another as Hilda Downing Bump. These were articles on Ray DaBoll, a calligrapher, and Kenneth Butler, of the Wayside Press. If she published other articles, I have not been able to find them under the many possible variations of her name.

The exact sequence—and, indeed, nature—of events over the next decade or so are hard to arrange definitively from the fragments that exist. It seems that sometime around 1960 the Bumps divorced, or at least separated. An issue of Inland Printer from that year has a want-ad from her—name Hilda Downing Bump—requesting editorial or proofreading work in the Kansas City area. At the same time, George was in California getting an MS in mathematics from Stanford University. Subsequently, there appears a Hilda Downing doing library work in Missouri, first a high school librarian, later president of the Missouri Association of School Libraries, and eventually library supervisor at the State Department of Education. It may not be the same person, though, as in at least one case the middle initial is given as G. However, everything else lines up, including the dates. Downing’s name stopped appearing in the Missouri Library Association publications in 1968, and the social security death index lists Hilda Downing as dying December 1968 in Kansas City Missouri. She was 59.

On 8 May 1960, in Santa Clara, California, George C. Bump married Liselott A. Weidenkopf. He was 44. She was 29. I know nothing of her background. I believe that they had five children, all in California, all surnamed Bump. I do not know Bump’s occupation—but his avocation seems to have been writing. He had a philosophy of life which he wanted to elucidate and he did so in what seems to have been extensive correspondence, although only fragments remain—at least, that’s all I have found.

As best I can tell, Bump’s correspondence began in the mid- to late-1940s, after he had married Hilda and when they were living in Chicago. He was in correspondence with the Fortean Society, of course, as well as the magazine The Humanist, which was weakly allied with the Fortean Society through its editor, Edwin H. Wilson, and some shared members. He was also in contact with Thayer himself and Eric Frank Russell. In addition, he wrote to the socialist journal The Word, the anarchist The individualist and the Irish paper The Leader, and other writers including—but probably not limited to—Rudolf Rocker and Frank Chodorov. He appeared in the letter column of The Chicago Tribune. Much later, letters would go to The New American Mercury, the Oxnard Press Courier, the California Board of Equalization, and the Stanford Daily. Together, the letters show the continuity of his thought over the years as well as some dramatic turnabouts.

In the most blunt terms, George Christian Bump of the 1940s was an egoist, a radical individualist. He considered himself something of an anarchist. There were many others associated with Fort with a similar bent—Benjamin de Casseres, for example, held similarly radical egoist views, as far as I can tell, but Bump’s anarchism ran rightwards, different than many—not all!—of the Forteans, who tended toward a left-libertarianism. Nonetheless, he could appreciate the socialist magazine The Word because, as he said, “I do not accept the economic (Marxian) interpretation of history. I believe that history is created by a force of character. But I am convinced that ‘The Word’ is on my side in the battle because it is radical and whatever is truly radical expresses truth.” The battle he mentions—that was the battle between the individual and society.

Bump laid out his ideas in a series of letters to Eric Frank Russell—internal evidence suggests that there may have been a dozen or more, of which only two survive. One dated 30 November 1947, though digressive, maybe bests summarizes his thought; at least, it seems in accord with what he wrote elsewhere, but also more expansive, even if not closely argued. The relevant excerpts:

“The way I figure it, anarchism means ‘Live and let live.’ State-ism is the policy of the dog in the manger.

“I think the principle of leadership, that is, feudalism, is inherent in Nature. But out of this there has grown a certain form of perversion, disease, and parasitism known as the court. The court grows up originally around some outstanding man and consists to begin with of his wives, aides, and hangers-on. When this man dies, the court assumes control, choosing another individual to replace him.

“It would be hard to say at just what point the system becomes perverted. But at any rate, all the courts existing now are depraved; and so I say arbitrarily that all Nationalism is depravity and perversion.

“I maintain that we shd deal with each other as one individual to another rather than thru the court. In other words, I advocate feudal (man to man) relations rather than relations of masses to masses.

“Out of court there develops the system of church and state, ruled ostensibly by Parliament but actually by a secret priesthood. There may be good men in Parliament but the system of Parliamentism itself serves to maintain the rule of a degenerate and depraved priesthood.

“We are apt to dismiss the Church as unimportant becuz we think it has little power. But the church, like the royal family, forms a necessary part of the system. It is a pattern, a complex, called in the Bible ‘Satan’ or the ‘Whore’. I call it the great vampire.

“Local autonomy is a step in the direction of anarchy. As reported in ‘Freedom’, one of the anarchist leaders during the civil war in Spain advocated local autonomy as a step toward anarchy.

…….

“By heritage and natural affinity I belong to the [Irish] Dissenters. The Dissenters are of an individualistic tendency and are inclined to regard the Roman and Anglican Church as out of the same pattern. The Dissenters are to some extent opposed to the system of Court-State-Church in principle. In a way I am merely an extreme Dissenter.

“You may say, ;Why be a Dissenter? Why not just ignore the church?’ I do ignore the Church in that I do not try to change the personal opinions of the church-goer. But I think something can be accomplished by calling the attention of those who are actually Dissenters to the nature of Church and State.

“The way I look at it, Jesus was not a god anymore than anyone else is but a man, a man opposed to the system of church and state. Jesus clearly stated that he was a god only in the sense that we are all gods (that is, immortals). The priests killed him becuz he was undermining their system.

“The story of Jesus has been added to by various individuals, many of them with the old priestly preconceptions. But the naked outline of the story stands out in all clarity. Jesus was a great spiritual leader. The priests made him a god so that they could utilize his memory for their own purposes.

“It is always man versus God. God is a function of priestcraft, something degenerate and depraved. A true man is infinitely superior to any god.

“The ‘whore’ has always ruled England thru the court. At the time of Queen Elizabeth, the court was dominated by agents of Spain and the pope. With slight variations, Satan still controls England as every other country in the same way.

………

“I have often thot of writing a story (or many stories) on the future of mankind, involving the development of new nations of many kinds (feudal, democratic, theocratic, etc.). I am sure I could write fascinating (to me) stories. But I have too many other thinggs to do. I cd exemplify my principles of local autonomy by letting small nations and individuals (in my stories) defeat the world-state. The more I think about it, the more I like the idea. Even if my stories are never publisht, I wd get great satisfaction out of seeing the world-state and its agents defeated, even in a story.”

Elements of this philosophy appeared in Bump’s various other missives from the late 1940s. His letter to The Humanist, for example, posited the eternal struggle between individual and the state. An October letter to the Chicago Tribune used the then-dominant historical position that the American Civil War was fought over state’s rights to wish that “The Confederacy should have won the war. If the principle of states’ rights had been upheld, we probably never would have had the financial tyranny of the federal reserve system, the destruction of individual spirit and our economic well being thru the income tax, or the subservience of the United States to English policy in the last two World wars. Tho they were defeated in battle, to the Confederacy still belongs the victory for the eternally right: it is only a question of time until this is recognized by everyone.” An earlier letter to the same paper—from June—was similarly anti-English: in regards to the Jews and Arabs battling over Palestine, the real answer, for Bump, was “for the English to get out and let the Jews and the Arabs settle the matter among themselves.” (No doubt these prejudices irritated Russell.)

Of course, these themes were often reflected in his correspondence with the Fortean Society. Indeed, his individualist philosophy informed his reading of Charles Fort.

Exactly when George and Hilda joined the Fortean Society is impossible to say—just as I cannot say when they first read Fort or why they were attracted to the Fortean Society. Their first connection to Fort that I can find is Thayer’s mention of their marriage in the pages of Doubt. He calls them esteemed members, and they may have been, but neither of their names appear in Doubt before that, and I can find no mention of Fort in any of their writings from before that time, either. Indeed, Downing’s name would appear only once more in Doubt, and that in association with her husband, raising the question of whether she had any interest in Fort at all. (One might say that her time classifying library books was something of a Fortean endeavor, but I have no evidence that she made the connection.) That second—and final—mention of Hilda Downing came in Doubt 24 (1949), and was part of an announcement of several Fortean marriages—the Bumps, the Drussais, the Youds, and The Gaddisses. The article included a picture of each of the couples.

George, on the contrary, was active in the Society. At the time, the Society was experimenting with chapters—local Fortean Societies. Chicago was the second city to form one (making it Chapter 3, in Fortean fashion, Thayer’s operation having the honor of being Chapter 1), and Bump was among those involved—local autonomy, right? Thayer wrote in April 1949, “No general meeting has been held, principally from lack of a hall, but members Castillo, Bump, Brady, Hurd and others are in organizational conferences pretty much all the time. The explosive potential is enormously greater than anything Lillienthal dreams of--what with provivisectionist ‘Ajax’ Carlson, anti-vaccinist Hurd, rocketeer Farnsworth and pro-Kantian Brady all wrestling in the same cyclotron.” Supposedly, Bump was giving lectures in Chicago at the time, and he incorporated Fort and his books into the talks. Otherwise, he contributed to Doubt more than a dozen times, some of those contributions substantial, and related to his interest in individualism.

Bump had the typical Forteans fascination with anomalies, but these often carried political overtones—when they weren’t directly matters of politics and philosophy. His correspondence with Eric Frank Russell showed a similar inclination—notes on a man said to live to 152, the superior vascular system of ‘negroes’, the increasing population of Arab countries, prejudice against a fortune-teller by the police, the declining buying power of the average worker, oddities surrounding the Lincoln assassination, the tendency of Catholics, Democrats, and socialists to disdain individuality, the Encyclopedia Britannica article on civil liberties, the tendency of mainstream press to ignore developments in the Arab world, including French colonialism—a Fortean damned fact, but of a very political bent.

Perhaps the most strictly non-political was the material he sent in on flying saucers and the fire-starting girl of Macomb, Illinois—but since Thayer credited him generally, alongside many others, it is hard to know what Bump thought of those phenomena; indeed, many of the credits Thayer gave to Bump were generic and not correlated to specific reports. There were enough, though, to show that Bump had a healthy skepticism for authority. He sent in a story about a woman who was supposedly so allergic to anesthesia that she exploded on the operating table, for instance, and he seems to have been suspicious of the fluoridation of water, like Thayer. In 1952, he told Thayer the story of attending a Christian church where the proposal was put forth that members should not sue each other—and it did not pass, which prompted Bump to leave. Thayer thought the idea good, and wanted to one-up the Christians, so suggested Forteans adopt the practice. (Nothing seems to have come of the matter.)

Thayer did not seem to appreciate Bump very much—which wasn’t uncommon. He disdained a number of Forteans. And even friends could find Thayer tiresome and tedious. One gets the sense that Thayer was very alone, except for his wife. In April 1948, he chided Russell for indulging Bump with any attention: “You are a sucker to answer Bump. He picks on you because I bush him off. Don’t do it.” Which suggests that there was at least a one-sided correspondence between Bump and Thayer, although none of it seems to have survived. Probably, like others of Thayer’s Fortean correspondents he simply tired of not getting answers and so just sent in material. He did that until the mid-1950s.

Despite Thayer’s dismissal of Bump, he gave him a lot of space in Doubt—not just with the credits and small reports, but with recommended readings and short essays. (Bump had provided Russell with the same in correspondence, recommending books and including harangues.) In particular, Bump had occasion to publish lengthy (for Doubt) pieces in issues 25, 26, and 37—that last being 1952. These were largely amplifications of the philosophy that he had laid out in his letters to Russell—and elsewhere—with recommendations that Forteans read certain books. These three—let’s call them essays—demonstrate that Bump, like Thayer, was skeptical of modern society and government, and let that skepticism influence how he read and understood Fort—which is not to say that there is one right way to read Fort, but that Bump and Thayer had an overlapping (but not congruent) political interpretation of Fort and Forteanism.

The first essay, appearing early in 1949, most clearly showed Bump’s political view of Forteanism. He started by recommending Frank Chodorov’s book The Myth of the Post Office. Bump had earlier recommended Chodorov to Russell; he liked his anarchism, but recoiled at his leftist sympathies, he told Russell, and made a similar point in Doubt: “Chodorov is intent (like Nock) on attacking the ‘State’, which I identify in principle with the ‘Orthodoxy’ which Fort and Forteanism attack. Chodorov claims to be advocating ‘social power’ as against the power of the ‘State.’ But actually and by logical necessity he is advocating freedom of ‘private enterprise’ to operate and grow.

“Fort in opposing orthodoxy is also advocating freedom of enterprise altho he makes reference to it only rarely, as on page 588 of The Books where he says: Resistance to notions in this book will come from persons who identify industrial science, and the good of it, with the pure, or academic sciences that are living on the repute of industrial science.

“The basic conflict is between growth and reaction, between those who want to grow and want sufficient ‘freedom of enterprise’ in order to grow and those who cannot or will not grow and therefore can only act as resistance to growth, as mass, inertia, reaction.

“The resistance to growth is partly human and partly non-human, hidden, esoteric, occult. It tries to keep hidden because to the extent it is understood, it loses power.

“To the extent that an individual is ‘de-horned’ and loses his power to fight effectively against the hidden control, he is sanctified and blessed and becomes a part of orthodoxy, a mere puppet of the hidden control.

“The official advocates of both ‘free enterprise’ and its theoretical opposition, socialism, are zombies, mindless agents of the hidden control. They are always united in opposing any real freedom for growth.

“The purpose of their sham battle is to distract attention from the real war, which is between growth and resistance to growth, and the inevitable result of which is the gradual victory of growth.”

This reading of Fort is unusual, although credible—to an extent. As Bump himself admits, Fort rarely discussed economic matters, and certainly made no brief for free enterprise. (One could only assume that he would have mocked the notion of an invisible hand guiding capitalist development, as the image is so absurd.) The quote from Fort comes amid a more general discussion of how science has come to get to much credit for civilization, and Fort needed to acknowledge that some science, indeed, had helped humanity, but of a limited, qualified kind—what others, including Thayer, would call technology. At no point does Fort associate this science with capitalism, but Bump’s reading is not ruled out by what Fort says—it’s just an extension, suggesting that Bump’s real interest was never really Fort but political and economic philosophy. Admittedly, though, that he could quote a small fragment from the Books (Lo!, as it happens) shows he had read Fort carefully.

The next issue of Doubt had Bump bringing a most obscure tome to the attention of Forteans—an 1853 book by the polymathic Charles W. Webber (journalist, explorer, medicine man, theologian) called “‘Spiritual Vampirism: The History of Etherial Softdown and her Friends of the “New Light”’. As Bump glossed it, the book claimed that vampires were real, although they fed not on blood, but a spiritual energy called the Odic fluid: the active principle of life, something like the body’s own subtle electricity, which connects the materials and spiritual worlds—is, indeed, the only means of communication between the two. According to Webber—who was wary of revealing too much—great leaders had an excess of Odic fluid, which they could use to fill their followers. Others were deficient, their nervous systems out of whack, and they need to feed on the Odic fluid of others. These were parasites. These are vampires.

Bump concluded by connecting Webber’s theories to the suppositions of Fort—Webber, he insisted, was telling a true story: the book “describes reality. This book tells in factual detail what the writers of horror fiction only hint at.” So then where are the vampires? They form hidden cults. “Vampirism must be organized in some way to keep mankind in ignorance. This would explain the campaign to ridicule against the study of psychic phenomena. For to the extent that these things are understood it becomes difficult for vampires to practice their arts. If, as Fort hazarded, we are owned and exploited by a hidden entity, these ‘human vampires’ may act as media by which the vitality of the human race is drained off to support the life of the supreme vampire which holds humanity in thralldom.”

The theory represented a fairly paranoid view of history—not inconsistent with other Fortean ideas, at that. Paranoia was common among Forteans. The question that Bump’s ideas immediately raises, of course, is who are these vampires? If we go by his 1947 letter to Russell—the church was a vampire. The state, in its way, too. One is tempted to say—as Bump was drawn to synthesizing all forces into two polar sides—the vampires are the orthodox themselves. (Incidentally, the horror writer Dan Simmons wrote a book on this theme many years later, the much-too-long Carrion Comfort). Again, for Bump, Forteanism helps explain politics and economics more than it does science.

The third essay concerned Max Stirner and his book—translated into English as The Ego and Its Own, which was of interest to a number of Forteans, including Thayer, its rarity bedeviling those who wanted to develop their ideas about anarchism. Bump wrote, “I think that all Forteans should read Max Stirner’s ‘The Ego and His Own.’ Stirner clearly shows the fundamental falseness of Orthodoxy and therewith the means to overthrow it. Orthodoxy assumes (and must assume) that Universals are the true Reality. But Stirner pointed out that the Real is the Particular, not the Universal. The reality of each individual lies in his Uniqueness, not in his partaking of universal qualities. Thus an individual may be a man and an American. But he is more than that--he is himself!

“As I see it, all conflicts are related to conflicts of thought and the fundamental conflict of thought is between realists and escapists, what William James called the tough-minded and the tenderminded, The realist tries to deal effectively with reality; the escapist tries to escape from reality.

“Please don’t misunderstand me. I am not saying that it is the only conflict. I am merely saying that it is the most fundamental conflict. I think that war is inherent in life but that the destructiveness of war is minimized by realism.

“To some extend [sic] we all try to escape from reality (the outer reality) in order to preserve our individuality. This represents in some degree a war with reality. The difference between the realist and the escapist lies in this, that the realist always recognizes that the outer reality is there while the escapist tries to convince himself of its non-existence.

“Universalism is the manifestation of escapism. The escapist finds the actual world too disagreeable to face; so he tries to replace it by a world of universals, that is, ‘heaven.’

“The realist carries on personal wars as he has to in order to maintain his existence in this world. But the universalist is engaged in a war against reality itself. He is at war with ‘this world.’

The escapist (universalist) comes into contact with reality in great part through contact with realists. Hence his war against reality takes the form of a war against realists.

“Stirner thinks that all feelings (as affection, etc.) are manifestations of egotism, that (for example) an individual likes to see another individual happy because this in turn brings him pleasure. With this I do not entirely agree. I think that every emotion, every passion, has a certain autonomy, a life of its own. In proper development, all the emotions, including egotism, are in harmony. But it is possible to convert certain emotional tendencies into anti-egotism, to turn the individual against himself.

“Nietzsche describes how this is done by Christianity. We hear a lot now about schizophrenia (split personality). Is it not possible that all schizophrenia is the product of Christianity or its derivatives?

“The diversion of the passions so as to turn the individual against himself is of course the work of the escapists (universalists). It might be said that universalism is a self-created disease while schizophrenia is a disease imposed upon one by others. Perhaps the two diseases are to be found together in the same person.

“The universalist thinks that he is escaping from ‘this world’ into freedom. But actually he is imprisoning himself. He bounds himself on all sides with rituals and dogmas so as to keep out the icy breath of reality.

“Always gnawing at the vitals of the escapist is the fear of reality resulting from the subconscious knowledge that he has not overcome reality but only escaped from it temporarily. He is always in need of assurance that he is right. So he seeks ‘converts.’ He can maintain his illusional world only by the constant reiteration that it is the real world. This is called ‘prayer.’ He has ‘faith’ that he has overcome the real world. But in his heart of hearts he knows that it is not so. To still this inner voice he congregates with others in ‘churches,’ thinking by the power of numbers to establish the supremacy of faith over reality. But ultimately it is all in vain.

“Growth, expanson [sic], is the tendency of all life, even of the perverted and diseased life. So the illusionist, the escapist, seeks to spread the boundaries of his ‘Church.’ But what to him is freedom from reality is to the realist only imprisonment from reality. Hence the continual revolt by ‘individualists’ against the dogmatism of the Church and its derivatives, ‘modern science,’ the priesthood of medicine, etc.

“In the cult of ‘modernism,’ the doctor has taken the place of the priest. The ‘selfless’ labors of the doctors to deliver people from the consequences of thir [sic] follies by ever-new forms of magic, none of which ultimately succeed in their purpose, is the vicarious atonement over again. The phrase ‘men in white’ suggests the sacredness of the temple. Universalists always prefer the colors black and white because of their ‘abstract’ quality, their conveying of the quality of ‘not being in this world.’

“To me Forteanism represents the revolt of the realists (the ‘individualists’) against the church of modern science and the ‘men in white’ (the new church which has been erected with the dogmas of science as a foundation in an attempt to preserve the illusional world of the escapists against harsh reality).”

Bump’s thoughts on Stirner are perhaps the most revealing of Forteanism more generally at the time—not that there weren’t many varieties of Forteanism, for there were, but that they often shared a central core. This core was the focus on the individual—anomalous events are individualistic by definition. Science, at the time, and society more generally, were tending toward the statistical. Forteans stood against this trend, particulars in a statistical universe. In this case, then, Bump’s political reading of Fort, although idiosyncratic in many ways, got at a common anxiety among the Forteans, that the world was erasing them, turning them into naught but a number.

Bump last appeared in a 1958 issue of Doubt, but that material may have been saved from an earlier submission. Certainly, the Fortean Society was almost at its end, going out of business in 1959. But The timing makes sense with his life circumstances—it was around this time that he seems to have divorced Hilda, went back to California, remarried, and received a degree from Stanford. Forteanism certainly could have been squeezed out by those events. Further suggesting that it was a change in Bump, and not the loss of the Society, that altered his Forteanism, I find no record of him discussing Fort in the years after the 1950s, nor do I find him associated with later Fortean organizations, which tried to pick up from Thayer and recreate his mailing list. It is not definite, but given Bump’s various interests, it is likely that he would have heard from the International Fortean Organization that formed in the 1960s, but, if he did, he stayed aloof from it.

He did not stay his letter-writing hand, though, and these show that politics continued to consume him, some of his ideas remaining the same, others changing dramatically—at least based on the evidence available. He wrote into the new American Mercury, which had taken a hard-right since its early days under Mencken, arguing that people should be allowed to have as many children as they wanted and warning about the dangers posed by Cuba. He also sent in material to a southern California newspaper—that was where he was living at the time, southern California. Probably, there are more examples of his correspondence that I have not found.

In the late 1960s, and through the 1970s, he became legally entangled with California’s Board of Equalization—which collected taxes. Bump and his wife, it seems, refused to pay taxes and filled out their forms in unorthodox ways—writing “object” on the blanks in at least one case. The Board, using bureaucratese, explained Bump’s argument: “In his petition, amendment to petition, motion for summary judgment and other documents filed with the Court, petitioner alleges that he received no amount in dollars during the years here involved since the only legal dollars are gold and silver or certificates redeemable in gold and silver, and that his rights under the 5th, 7th, 8th and 9th Amendments to the Constitution have been violated by depriving him of property without due process of law, depriving him of the right to trial by jury, inflicting cruel and unusual punishment upon him and depriving him of services by public servants who have taken an oath of office to defend the Constitution of the United States.”

The most surprising turn of events was recorded in the Stanford Daily. A 1979 letter from Bump castigated homosexuals—“Are there any individuals or groups at Stanford who regard homosexuality with abhorrence and who resent the attempt to ‘brainwash’ them into accepting homosexuality and treating gays with ‘sensitivity,’” he wanted to know, because it was obvious to him “every sane human being regards homosexuality with instinctive abhorrence.” This stance against gays cut against his individualism; more interesting, though, was he cited the Bible in support of his position. That this wasn’t a historical but a theological point was made clear in another letter, this one from 1981. Americans had to accept biological limits, he said—again going against his previous individualism—biology dictating that women could not be measured against men and that there were heritable differences between the races. (So much for no universals!) He then went on to complain that feminism, the sexual revolution, and abortion—which was the immediate cause of the missive—resulted from a loss of religious instruction.

It is hard to imagine that the arch-egoist, the man who called the state a vampire and the church a whore could pen the following words, but he did. Conservative he remained, skeptical of the government he remained, but no longer was he anxious about the influence of the church, no longer did he think nationalism and the state against nature, no longer did he set the individual against universals: he embraced the universal, in just the way he had castigated Democrats, socialists, and Catholics of doing so many years ago: “Some individuals may succeed in living virtuous lives without being associated with any institutionalized religion; but collectively mankind cannot survive without religion. The human race is inherently religious; and no nation has ever existed or can exist without religion. (The socialist anti-religious so-called nations are parasitic entities which will perish when we stop giving them aid and support.) America is a Christian nation and people; and when we cease to be Christian, we shall cease to be either a nation or a people. Christianity is based on the Bible; and the Bible condemns infanticide above all other crimes. It provides the death penalty for causing abortion.”

It would be fascinating to know exactly how Bump’s views changed over those thirty-five years, his right-leaning respect for free enterprise and disdain for socialism coming to support not individuality and egoism any longer, but rather the very things that he once claimed to hate most of all. And it would be interesting, too, to know if Forteanism played any role in this evolution, although that does seem doubtful—not because it is impossible to have a strongly conservative Christian reading of Fort, but more banally because he seems to have lost interest in the Bronx philosopher.

As best I can tell, Bump lived in southern California during the mid-1980s, at least, moving, perhaps, from Moorpark California to Thousand Oaks. (The Ronald Reagan Presidential Library is sited between those two cities.) He lived a long life, passing away in 2013 at the age of 98. At the time, he was in Longmont, Colorado. A short obituary I found gave only his birth and death dates.