Another Fortean who seems to have disappeared as the 1940s turned to the 1950s.

George Charles Bowring was born 1 Feb 1912 in England to George Henry Stockes-Bowring and the former Ada Hubbard. I know nothing about the senior George; Ada had left school in second grade and would do some work as a seamstress. Sometime before 1923, George Henry died. The widowed Ada left behind a married daughter and took her ten year old son to be with her parents in Los Angeles. They traveled first to Toronto, then passed into the U.S. via Detroit on 24 October 1922. By 1930, Ada had remarried—Tom Irons, who had come over from England himself, in 1909. Tom had quit school in fifth grade and worked as a machinist.

George Charles also left school early, only completing his second year of high school. In 1930, he worked as a linotype operator for a newspaper. Three years later, when he was naturalized, he worked as a chauffeur. Given his later employment history, the job indicates that the Depression may have forced him into work he really didn’t want. Three years after that, he married the former Virginia Teagarden. Virginia was four years his junior—20 to his 24—from Texas, and a college graduate. By 1940, he was back to his chosen profession, linotype operator, and living with Virginia. The family had also taken on a boarder. Ada and Tom were still in the LA-area, too, Tom a machinist and Ada a homemaker. She had still not been naturalized, although Tom had been.

Naturalized and of age, Bowring would have been available for the draft, but I can find no military or draft records for him—which doesn’t necessarily mean anything. Wendy Elizabeth Bowring was born 17 November 1942. Edwin Wallace Bowring was born 10 June 1945. Bowring seems to have joined to Fortean Society between the north of his two children—at least that’s when he gets a mention. There were also changes in his job life around that time.

George Charles Bowring was born 1 Feb 1912 in England to George Henry Stockes-Bowring and the former Ada Hubbard. I know nothing about the senior George; Ada had left school in second grade and would do some work as a seamstress. Sometime before 1923, George Henry died. The widowed Ada left behind a married daughter and took her ten year old son to be with her parents in Los Angeles. They traveled first to Toronto, then passed into the U.S. via Detroit on 24 October 1922. By 1930, Ada had remarried—Tom Irons, who had come over from England himself, in 1909. Tom had quit school in fifth grade and worked as a machinist.

George Charles also left school early, only completing his second year of high school. In 1930, he worked as a linotype operator for a newspaper. Three years later, when he was naturalized, he worked as a chauffeur. Given his later employment history, the job indicates that the Depression may have forced him into work he really didn’t want. Three years after that, he married the former Virginia Teagarden. Virginia was four years his junior—20 to his 24—from Texas, and a college graduate. By 1940, he was back to his chosen profession, linotype operator, and living with Virginia. The family had also taken on a boarder. Ada and Tom were still in the LA-area, too, Tom a machinist and Ada a homemaker. She had still not been naturalized, although Tom had been.

Naturalized and of age, Bowring would have been available for the draft, but I can find no military or draft records for him—which doesn’t necessarily mean anything. Wendy Elizabeth Bowring was born 17 November 1942. Edwin Wallace Bowring was born 10 June 1945. Bowring seems to have joined to Fortean Society between the north of his two children—at least that’s when he gets a mention. There were also changes in his job life around that time.

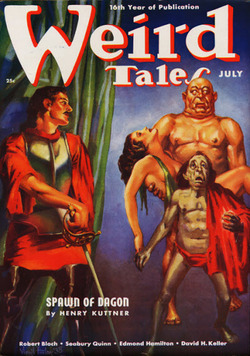

Bowring had been involved in the production of newspapers and books. But he was also a fan and a collector—including a fan of fantastic and weird stories. He had letters published in the July 1938, January 1939, and May 1939 issues of Weird Tales, for example. He was also, understandably, interested in books on the graphic arts [See Inland Printer, American Lithographer, vol. 117, 1946, p. 70.] Some time between 1946 and 1948 he started selling books [See Antiquarian Bookman 1948 p. 1161]. He especially favored selling books of fantasy [See Hobbies vol. 54 1949 p. 140]. It may be that Bowring was still in the book production business, the exact amount of time taken and money generated by his book selling unclear.

Virginia Bowring died young, passing away in October 1956, just a few months after her forty-first birthday. George was a widower, then, with a girl just about to turn fourteen and a boy recently turned 11. Elizabeth would marry a few years later, in 1961, not quite 20. Edwin would marry in 1966, just turned 21. George remarried, too, in 1961, eight days before his daughter—which indicates either a week of celebration or a serious falling out. He was forty-nine, and his life had repeated many of the patterns of his mother’s: marriage, two children, death of a spouse at a young age, and remarriage.

George Charles Bowring died 9 September 2001 in Eugene, Oregon, aged 89.

There is an obvious hint as to how Bowring became interested in the Fortean Society, although nothing definitive. Certainly, his love of fantasy and weird literature was shared by a number of Forteans and had brought some into the Society. And thee’s every indication that he, like so many Forteans and science fiction fans, but not like Tiffany Thayer, enjoyed stories about flying saucers. Thayer preferred when reports were just lights in the sky—as in the case of a streaking something above the Midwest, which was seen, according to Thayer’s odd reckoning of time, on the 13th day of the month of Fort, which Thayer took “celestial approbation for the adoption of the Thirteen Month Calendar by the Fortean Society, and direct approval of the name Fort for the month.” Bowring was among those who sent in clippings on the event [Doubt 11, 154]. He also sent in reports of another something in the sky that fellow Fortean N. Meade Layne took to be the craft Careeta [Doubt 17, 252], and a black spot on the moon that astronomers dismissed as the moon’s seas but Thayer joked was the Careeta preparing to conquer earth [Ib., 254]. When “lights in the sky” became flying saucers, Bowring kept sending in reports, which were digested in Thayer’s occasional sops to the membership, as well s similar reports—such as on meteors and strangely colored clouds [Doubt 30, 35-36].

General Forteana fascinated Bowring, too, and he went out of his way to be of service to the Society. He sent in reports on mysterious volcanoes [Doubt 14, 207], water monsters [Doubt 14, 209] and blue frogs in New Jersey [Doubt 14, 212]. He noticed the same story about a living lizard and frog found in 2,000,000 year-old rock that had caught Kerr’s eye [Doubt 17, 258]. A stop sign disappeared amid the smell of dynamite, and Bowring sent a clipping to Thayer; similarly when a pack of half-wild dogs killed a pet deer in Pasadena [Doubt 18, 267; 274]. And, of course, living in Los Angeles he was attuned to stories about smogs and fogs, especially of the killer variety [Doubt 29, 18]. These held a special place in Fortean history, for it was killer fogs in Belgium around the time of the Society’s original founding that ere given as an example of the necessity of the word of Fort to be spread.

Bowring knew Thayer’s pet interests, and kept him supplied with relevant clippings. When geologists reported contradictory things about whether seismographs had recorded rumblings from a nuclear bomb test, Bowring passed on the stories [Doubt 16, 237]. (Thayer thought seismographs were like lie detectors: phony. But at least not an assault on civil liberties.) Something fell out of the clear blue sky in Los Angeles, and a reporter breezily noted that it was just discard from a passing plane—as if, Thayer thought, that would end the discussion! Even if that answer were right, it indicated a problem: slag was falling 30,000 feet onto people. From planes. That cannot be dismissed. [Doubt 27, 410]. And when Thayer was trying to put a name to the phenomena of stray bullets, it was Bowring who invented the one Thayer would use—ballisterics [Doubt 16, 239].

Bowring went above and beyond the usual catering to Thayer when he sent in an actual Fortean artifact:

“MFS Brod and others sent in the Acme Telephoto of a fish with four legs, caught Nov. 1, 19 FS, at Los Angeles, but MFS Bowring, went them one better. HE sent us the FISH.

Accto Bowring, he went first t the newspaper office where the specimen had been photographed. There he was referred to a local embalmer who had the fish in hand. The undertaker—no taxidermist, as appears—had ‘dipped’ the quadruped in formaldehyde. Alas, that expedient was not sufficiently preservative to insure transcontinental air flight in perfect condition. Bowring sent her (or him) air express, and that caused delay of delivery in New York City. So that the package had attracted a lot of attention in the offices of the express company before delivery could be made. In short, the package was opened by the expressmen and the Forteana destroyed. We mourn the loss, and we are impressing the express company with the enormity of its action, but we have learned by this experience too.

Members are requested to use Parcel Post rather than express whenever feasible.

We are deeply grateful to Bowring for trying, however. Better luck next time!” [Doubt 27, 411.]

Thayer titled the column “Fortean Loss,” which was also the title he used for obituaries of Forteans.

Bowring’s chief interest in Forteana, though, seems to have been spontaneous combustion. His second mention was for three stories on pyretic incidents—as Thayer called them: a movie director burning in his bed after he fell asleep while smoking, and two older women burned in smaller conflagrations, the presence of cigarettes not established [Doubt 11, 164]. Interestingly, the stories all came from 1941, which might suggest that Bowring had been interested in the Society since then—that was, after all, the year Fort’s omnibus edition came out—and sent them to Thayer, who had sat on them until late 1944, or that Bowring himself had held on to the clippings that long, or even that he was going back and re-reading old newspapers. Over the years, Bowring sent in enough clippings in the subject that Thayer named him “chief of our pyrotic department.” Like Thayer, Bowring was dismissive of official explanations, as when the LA Fire Department showed how flammable clothes were—“an effective way of stilling any isolated charges of spontaneous combustion,” Bowring sniffed [Doubt 14, 208].

Why the interest in spontaneous combustion? The available record offers no answer. Nor does it explain Bowrings drift from the Society, or exactly when that happened. He was in Doubts 11, 14, 16, 18. Then there was a lay-off from late 1947 until late 1949, when Bowring came roaring back with the four-legged fish. Doubts 29 and 30 had his name, dated July and October 1950. And those may have been his last actual contributions.

His name did appear in Doubt 43 (February 1954), but it’s not clear he had recently been in contact with the Society. Thayer wrote a digest of recent events, this time focusing on killer fogs and smogs, and at the end he name-checked Bowring. But the clippings he mentioned went back to 1951, and those he just hinted at went back even further. He very would could have been working through a file that included reports Bowring had sent in years before.

Certainly, by 1958, Thayer was wondering aloud if Bowring was still active. He was again going through a phase to organize Forteanism, this time by assigning Forteans a topic to keep tabs on and write up regularly. Among the topics was pyrotics, of course. Thayer wrote that it was assigned, then added, “but are you still active?” [Doubt 56, 480]. The assignee was almost certainly Bowring. There was no response, though. Like other Forteans active in the late 1940s, he had moved on to other matters.

Virginia Bowring died young, passing away in October 1956, just a few months after her forty-first birthday. George was a widower, then, with a girl just about to turn fourteen and a boy recently turned 11. Elizabeth would marry a few years later, in 1961, not quite 20. Edwin would marry in 1966, just turned 21. George remarried, too, in 1961, eight days before his daughter—which indicates either a week of celebration or a serious falling out. He was forty-nine, and his life had repeated many of the patterns of his mother’s: marriage, two children, death of a spouse at a young age, and remarriage.

George Charles Bowring died 9 September 2001 in Eugene, Oregon, aged 89.

There is an obvious hint as to how Bowring became interested in the Fortean Society, although nothing definitive. Certainly, his love of fantasy and weird literature was shared by a number of Forteans and had brought some into the Society. And thee’s every indication that he, like so many Forteans and science fiction fans, but not like Tiffany Thayer, enjoyed stories about flying saucers. Thayer preferred when reports were just lights in the sky—as in the case of a streaking something above the Midwest, which was seen, according to Thayer’s odd reckoning of time, on the 13th day of the month of Fort, which Thayer took “celestial approbation for the adoption of the Thirteen Month Calendar by the Fortean Society, and direct approval of the name Fort for the month.” Bowring was among those who sent in clippings on the event [Doubt 11, 154]. He also sent in reports of another something in the sky that fellow Fortean N. Meade Layne took to be the craft Careeta [Doubt 17, 252], and a black spot on the moon that astronomers dismissed as the moon’s seas but Thayer joked was the Careeta preparing to conquer earth [Ib., 254]. When “lights in the sky” became flying saucers, Bowring kept sending in reports, which were digested in Thayer’s occasional sops to the membership, as well s similar reports—such as on meteors and strangely colored clouds [Doubt 30, 35-36].

General Forteana fascinated Bowring, too, and he went out of his way to be of service to the Society. He sent in reports on mysterious volcanoes [Doubt 14, 207], water monsters [Doubt 14, 209] and blue frogs in New Jersey [Doubt 14, 212]. He noticed the same story about a living lizard and frog found in 2,000,000 year-old rock that had caught Kerr’s eye [Doubt 17, 258]. A stop sign disappeared amid the smell of dynamite, and Bowring sent a clipping to Thayer; similarly when a pack of half-wild dogs killed a pet deer in Pasadena [Doubt 18, 267; 274]. And, of course, living in Los Angeles he was attuned to stories about smogs and fogs, especially of the killer variety [Doubt 29, 18]. These held a special place in Fortean history, for it was killer fogs in Belgium around the time of the Society’s original founding that ere given as an example of the necessity of the word of Fort to be spread.

Bowring knew Thayer’s pet interests, and kept him supplied with relevant clippings. When geologists reported contradictory things about whether seismographs had recorded rumblings from a nuclear bomb test, Bowring passed on the stories [Doubt 16, 237]. (Thayer thought seismographs were like lie detectors: phony. But at least not an assault on civil liberties.) Something fell out of the clear blue sky in Los Angeles, and a reporter breezily noted that it was just discard from a passing plane—as if, Thayer thought, that would end the discussion! Even if that answer were right, it indicated a problem: slag was falling 30,000 feet onto people. From planes. That cannot be dismissed. [Doubt 27, 410]. And when Thayer was trying to put a name to the phenomena of stray bullets, it was Bowring who invented the one Thayer would use—ballisterics [Doubt 16, 239].

Bowring went above and beyond the usual catering to Thayer when he sent in an actual Fortean artifact:

“MFS Brod and others sent in the Acme Telephoto of a fish with four legs, caught Nov. 1, 19 FS, at Los Angeles, but MFS Bowring, went them one better. HE sent us the FISH.

Accto Bowring, he went first t the newspaper office where the specimen had been photographed. There he was referred to a local embalmer who had the fish in hand. The undertaker—no taxidermist, as appears—had ‘dipped’ the quadruped in formaldehyde. Alas, that expedient was not sufficiently preservative to insure transcontinental air flight in perfect condition. Bowring sent her (or him) air express, and that caused delay of delivery in New York City. So that the package had attracted a lot of attention in the offices of the express company before delivery could be made. In short, the package was opened by the expressmen and the Forteana destroyed. We mourn the loss, and we are impressing the express company with the enormity of its action, but we have learned by this experience too.

Members are requested to use Parcel Post rather than express whenever feasible.

We are deeply grateful to Bowring for trying, however. Better luck next time!” [Doubt 27, 411.]

Thayer titled the column “Fortean Loss,” which was also the title he used for obituaries of Forteans.

Bowring’s chief interest in Forteana, though, seems to have been spontaneous combustion. His second mention was for three stories on pyretic incidents—as Thayer called them: a movie director burning in his bed after he fell asleep while smoking, and two older women burned in smaller conflagrations, the presence of cigarettes not established [Doubt 11, 164]. Interestingly, the stories all came from 1941, which might suggest that Bowring had been interested in the Society since then—that was, after all, the year Fort’s omnibus edition came out—and sent them to Thayer, who had sat on them until late 1944, or that Bowring himself had held on to the clippings that long, or even that he was going back and re-reading old newspapers. Over the years, Bowring sent in enough clippings in the subject that Thayer named him “chief of our pyrotic department.” Like Thayer, Bowring was dismissive of official explanations, as when the LA Fire Department showed how flammable clothes were—“an effective way of stilling any isolated charges of spontaneous combustion,” Bowring sniffed [Doubt 14, 208].

Why the interest in spontaneous combustion? The available record offers no answer. Nor does it explain Bowrings drift from the Society, or exactly when that happened. He was in Doubts 11, 14, 16, 18. Then there was a lay-off from late 1947 until late 1949, when Bowring came roaring back with the four-legged fish. Doubts 29 and 30 had his name, dated July and October 1950. And those may have been his last actual contributions.

His name did appear in Doubt 43 (February 1954), but it’s not clear he had recently been in contact with the Society. Thayer wrote a digest of recent events, this time focusing on killer fogs and smogs, and at the end he name-checked Bowring. But the clippings he mentioned went back to 1951, and those he just hinted at went back even further. He very would could have been working through a file that included reports Bowring had sent in years before.

Certainly, by 1958, Thayer was wondering aloud if Bowring was still active. He was again going through a phase to organize Forteanism, this time by assigning Forteans a topic to keep tabs on and write up regularly. Among the topics was pyrotics, of course. Thayer wrote that it was assigned, then added, “but are you still active?” [Doubt 56, 480]. The assignee was almost certainly Bowring. There was no response, though. Like other Forteans active in the late 1940s, he had moved on to other matters.